More than One Edible Part! These Plants are a Great Addition to an Edible Landscape

Plants with multiple edible parts that make a great fit for an edible landscape.

By Steven Biggs

Harvest More…Harvest Something Different

Whether you're creating a vegetable garden or an ornamental edible garden, plants with more than one edible part are a great way to harvest more from your garden.

They're also a fun addition when preparing meals. There's been growing interest in nose-to-tail cuisine. For vegetable gardeners, the equivalent is stem-to-root cuisine!

Keep reading for 12 plants with more than one edible part.

Radish

Radish is a vegetable garden staple because it's virtues are many:

Radish seed pods are a tasty addition to an edible landscape!

Easy to grow.

Quick to mature.

Suited to in-ground beds, raised beds, and containers.

Can be inter-planted with slower-growing vegetables such as beets and carrots, and then harvested as those other crops need more space.

The radish root is what we most often eat. But there's more...

Radish: Other Edible Parts

The crunchy, mildly peppery seed pods are edible too.

The flowers are edible and make a nice garnish—or toss them into a salad

Some people use the leaves too. We've made radish-leaf pesto. Not my favourite—but taste is a personal thing.

Looking for crops for the shoulder seasons? Winter radish is a good winter storage crops. Find out about 25 storage crops to grow.

Rose

Rosehips and rose petals are both edible and a good fit for edible landscapes.

I swore off growing roses for years, having battled black spot on Mom's roses. But there are some fantastic disease-resistant roses out now. No-fuss for busy gardeners.

Roses are a must-have plant in an edible landscape. They add visual interest, they attract pollinators, they can be a focal point...and they have more than one edible part.

Most people think of rose hips (the fruit) when thinking of roses for edible landscaping. They're used for rosehip tea, rosehip jelly (and I've heard of rosehip vodka!)

Rose: Other Edible Part

You can use the rose flowers too! The petals are edible.

Use rose petals to make a rose petal jam, as a garnish, or add chopped rose petals to a bowl of cherries.

The inner, white portion of the petals can be bitter, and if it is, just remove this part.

Hear edible flower expert Denise Schreiber give her favourite edible-flower tips.

Arugula

Edible arugula flowers belong in any vegetable garden.

Peppery arugula leaves are a favourite in our household, whether in a salad or wilted on a pizza that's just come out of the oven.

Arugula is a great crop for the early spring edible garden. It tolerates cool conditions, and it's fast growing.

Arugula: Other Edible Part

Along with the leaves, arugula flowers are edible too. Let some of your arugula plants bolt and flower.

We use arugula flowers on salads and as a garnish. Like the leaves, they are mildly peppery.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Fig

Nothing beats a fresh fig! It's an exotic touch for edible gardens in cold climates.

(Remember, if you're in a cold climate, you can still grow figs as a potted plant, or as a plant that you tip over and protect for winter. Find out how here.)

Fig: Other Edible Parts

Use fig leaves in cooking for the unique taste.

There are a couple of other parts to the fig plant that make it a fun fit for an edible landscaping.

Fig leaves are packed with flavour. I describe the flavour as a mix of toasted almond and coconut. It's subtle. (You don't actually eat the leaf, but extract flavour from it.)

In our household, we like fig leaf panna cotta and fig leaf granita.

Before we finish with figs, here's one more idea for you:

Save the branches you prune from your fig tree for smoking meat. I like to smoke meat with apple or cherry...but fig smoke has a delicious taste of its own.

Cauliflower and Broccoli

Grown for their flower heads, these plants—along with kohlrabi, which we grow for its stout stem—have more edible parts!

See this recipe for cauliflower steaks!

Other Edible Parts

Use young leaves raw, in salads

Older leaves can be chopped and added to stir fries and soups

If you trim off the end of the stalk as you prepare cauliflower and broccoli heads to cook, keep those bits of stalk for stir fries. (I always add them to my beet borsch)

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Lemon

Like figs, potted lemon trees make a fine addition to edible landscapes, even in temperate regions.

A potted lemon tree is an elegant touch in a garden design.

Lemons add a sensory element to the garden too. Along with the lemon fruit, there's fragrance of the white flowers. Nothing beats the smell of lemon blossoms on a patio!

Lemon: Other Edible Parts

Lemon leaves impart a citrusy taste to food. These are wedges of halloumi cheese wrapped in lemon leaves, cooking on the grill.

Those fragrant lemon blossoms are edible too!

Don't stop there: Lemon leaves are packed with tasty goodness. They're tough—so don't eat the lemon leaves, but use them for their lemony flavour.

Use them like bay leaves.

Or wrap what you're cooking on the grill and it cooks the lemony flavour into the food. (Then just removed the charred leaves.)

A favourite in our household is wedges of halloumi cheese wrapped in lemon leaves and grilled. (Halloumi has a high melting point, so you can grill it without it oozing down into the BBQ.)

Find out more about cooking with lemon leaves.

Interested in growing a lemon tree in a pot? Here's more to help you grow a potted lemon tree. Lemons are a great plant to add season-long interest to your edible landscape.

Fennel

Florence fennel, a.k.a. "finocchio." Mom always included sliced fresh finocchio on a veggie platter.

I love to braise fennel bulbs in white wine.

Fennel: Other Edible Parts

Fennel flowers are edible, and the pollen can be tapped onto plates as decoration.

Beyond the bulb, the fern-like fennel leaves make a fine garnish.

Fennel flowers are edible too. (Or, tap fennel flowers over a white plate to decorate it with the yellow pollen.)

Fennel seeds are edible. Sprinkle a few over a bowl of granola. I like to add them when I make sausage.

There's also a cousin to the bulb-producing Florence fennel: Bronze fennel.

Bronze fennel is a perennial with aptly named bronze-coloured leaves. They're beautiful—and tasty. There's no bulb; this is a perennial edible we grow for its leaves, and its edible flowers.

If you're gardening to attract beneficial insects (pollinators, parasites, predators), fennel is a musts-have plant in vegetable gardens and edible landscapes.

Beet

Beet root is a great root vegetable for winter storage.

Beet: Other Edible Part

‘Bulls Blood’ beet leaves are a colourful addition to an edible garden.

Beet leaves are often overlooked.

Use small beet leaves fresh, as you would small chard leaves.

Larger leaves can be cooked. (An incomparable trio is beet leaves, sour cream and dill.)

Beet leaves are also nice chopped into a pot of borsch. (Here's how Mom made borsch.)

Most people don't think of beets when looking for visual appeal...but for colourful beet leaves—a vibrant red—check out 'Bull's Blood.'

Carrot

Baby carrots are a favourite summer treat at our house, and over the winter we enjoy carrots stored in our garage.

Carrot: Other Edible Part

Carrot leaves are edible, bringing their own unique flavour when added to sauteed greens or a frittata. Or, make them into a pesto.

Dill

Dill seeds are a great way to enjoy the flavour of dill through the winter.

Dill is up there with fennel when it comes to bringing beneficial insects to your garden. The flowers are a magnet for beneficial insects.

I cook with lots of dill, so when I have a glut of dill in summer I chop and freeze lots for the winter.

Dill: Other Edible Parts

Use dill flowers as you would fennel flowers.

And...I use the seed. Dill seed into a beet-and-feta salad is a delight. Or a few dill seeds into a pot of borsch.

Garlic

Garlic is a great crop for a home garden because you can grow enough of it in a small space for an entire household for a whole year.

And it stores well in a cool basement, even without a proper root cellar.

Garlic scapes

Garlic: Other Edible Part

Along with the bulbs, there are the garlic "scapes" that make a fine pesto.

And there's more...hear Doug Oster explain how he gets 5 harvests from his garlic.

Squash

Winter squash is a great storage crop.

Vining squash varieties are also a great addition to vertical gardens.

Squash: Other Edible Part

Eat some of your squash flowers. (Stuff them with a wedge of cheese, dip in batter, and deep fry, you won't regret it.)

Cook squash shoot tips. Hear chef Alan Borgo talk about squash shoot tips.

Squash flowers are edible. And don’t forget the edible shoot tips!

More Edible Landscaping Ideas

Articles: Edible Gardening

7 Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas To Grow More Food In Less Space

These Edible Perennials and Perennial Vegetables Make a Delicious Edible Landscape

Video: Edible Gardening

Edible Landscaping: See My Ornamental Edible Garden

Courses: Edible Gardening

Guide: How to Grow Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

Guide: How to grow ground cherries and cape gooseberries

By Steven Biggs

Unhusking the Husk Cherries

Looking for an easy-to-grow fruit for a northern garden?

Here are a couple of sweet, tangy annual fruit crops that are a snap to grow. They're great for container gardens too.

As you peel back the papery husk, inside you find a round, shiny yellow- or orange-coloured fruit.

(The whole business of peeling back the husk makes them very fun for kids...and adults too!)

In this article we take a look at the ground cherry (Physalis pruinosa) and its lesser known cousin, the cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana). They're both part of the nightshade clan—in the same plant family as tomatoes, peppers, tomatilloes, potatoes, and eggplants.

But they don't taste a bit like epplant or pepper, as you'll read below.

Ground Cherries

Ground cherry plants are fast-growing and sprawling, with small yellow-and-black flowers. They're probably the easiest to grow out of the nightshade clan.

A ground cherry plant will grow up to about one metre (3') high.

The taste of the berry is sweet and fruity. Some people liken them to pineapple.

Ground cherries are called by a few different names, including husk tomato, husk cherry, strawberry tomato, and golden cherry.

Cape Gooseberries

While it's not related to the true gooseberry, the tanginess of the cape gooseberry might account for it borrowing the name.

I've also seen this fruit called by other names including golden berry, goldenberry, physalis, and Peruvian groundcherry.

Growing cape gooseberry is worth the extra wait. The fruit is slightly larger, more citrusy, and a darker colour than ground cherry fruit.

Cape gooseberry plants are larger and more upright than ground cherry plants, getting up to about 1 ½ metres (4-5') tall. The fruit is slightly larger, citrusy, and a darker colour than ground cherry fruit.

Out of the two husk cherries, I prefer cape gooseberry.

But...there's a tradeoff: It takes longer to mature. As I explain below, there are a couple of things you can do to get cape gooseberries to mature more quickly in a northern garden.

(Cape gooseberry is a perennial in warmer climates...but we grow it as an annual in northern gardens.)

How to Grow Ground Cherries and Grow Cape Gooseberries

Both of these fruits are grown as annual crops in cooler climates. They're a good fit for the veggie garden or a container garden.

To get fruit as early as possible, start seeds indoors.

Start Ground Cherry and Cape Gooseberry Seed Indoors

A tray of ground cherry seedlings. Grow ground cherry and cape gooseberry seeds the same way as tomato seeds.

Treat ground cherry seeds and cape gooseberry seeds the same as you would tomato seeds.

That means:

Plant seeds 6-8 weeks before the average last frost date for your area

Plant cape gooseberry seeds earlier, as plants are slower to mature in cold climates (I aim for 8 weeks with mine, while I plant ground cherries about 6 weeks before the last frost)

Heat from below helps to speed up germination (a heat mat, or placing seed trays on a heated floor or radiator)

One other thing to think about:

Both of these crops self-sow, meaning that fallen fruit that you don't pick up gives you lots of little "volunteer" plants the following year.

Because ground cherries grow fairly quickly, I often let some of these little ground cherry plants grow. They fruit later than my transplants, but are still worth the space. But don't bother with volunteer cape gooseberry plants in a northern garden...they need too long a season.

Grow Ground Cherry Seeds

Ground cherry with the husk peeled back. They make a great garnish!

There are a few varieties of ground cherry seeds available.

Common ground cherry varieties include:

Aunt Molly’s

Cossack Pineapple

Golden Husk

There are also lots of unnamed ground cherry seeds for sale.

When it comes to cape gooseberry, I've never seen any named varieties.

Transplanting Ground Cherry and Cape Gooseberry Seedlings

Time your transplanting as you would for tomatoes.

You can transplant ground cherry and cape gooseberry seedlings into the garden when there is no longer any danger of frost and the daytime temperature is warm. I aim for 15-20°C (60-68°F).

If you've already transplanted your seedlings and the temperature dips, place floating row covers over them to keep them a bit warmer.

And don't forget the soil temperature: Cool soil sends them into a tizzy. If it's been a late spring, and the air is warm but the soil hasn't had time to warm up, it won't hurt to wait a bit before planting them.

Choose a Location

Ground cherries and cape gooseberries grow well in a wide variety of soil types.

Avoid very heavy and wet soils.

A raised bed is a great option for the cape gooseberry plant. That's because the soil in raised beds heats up more quickly in the spring—and that extra soil heat is helpful in a short season.

How to Plant Ground Cherries

When planting outdoors in the garden, space ground cherries and cape gooseberries about 60 cm (2') apart.

As you transplant seedlings, keep the soil level the same—don't bury the stem as is commonly done with tomatoes. That's because ground cherries and cape gooseberries don't root as readily from the stem as tomato plants do.

And here's something you'll be glad you did once harvest time rolls around: Mulch around the plants so that fruit that falls to the ground stays clean.

Growing Ground Cherries

Because cape gooseberry plants have a more upright growth, they benefit from a tall cage.

With their squat growth, ground cherries don't need any support or special training.

If you want, you can keep the plant a little bit more upright using a cage—but there's really no need.

Growing Cape Gooseberries

Because a cape gooseberry bush has a more upright growth, it benefits from a tall cage—or even from staking so that it doesn’t bend over on a windy day.

How to Grow Ground Cherries in Containers

Grow cape gooseberry and ground cherry in containers for an earlier harvest.

Container growing has two advantages in a home garden:

Warm Soil: The soil in containers heats up faster than the soil in the garden

Heat: You can situate containers for maximum heat and sunlight to speed up harvest (e.g. next to a warm wall or on a warm driveway)

Cape gooseberry plants benefit from extra heat in cool climates with a short season. This black sub-irrigated container has warm soil, and gives constant soil moisture.

Consistent soil moisture, warm soil, and well-fed soil give the best results.

To maintain soil moisture, consider a sub-irrigated pot (self-watering pot.)

Find out how to make your own sub-irrigated pot.

Harvesting Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

The papery husk turns from green to a tan colour as the fruit inside ripens. The colour of the ripe fruit depends on the variety, ranging from light yellow through to a pale orange.

Ripe ground cherries drop off the plant; ripe cape gooseberries remain on the plant.

If the fruit is still green, it's unripe. Don't eat it. That's because, like it's nightshade kin, the stems, leaves, and unripe fruit contain things that can upset your stomach.

Don’t eat green fruit, they contain toxins that cause stomach upset.

If you leave fallen ground cherries on the ground for a while, sometimes all that remains of the papery ground cherry husks is a fine netting—and you can see the golden fruit inside.

Store Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

Plants continue to grow and flower all season long. So when the first fall frost threatens, you'll have green, unripe ground cherries and cape gooseberries.

Pick these green fruit and let them ripen indoors. When spread out to ripen, many of them will ripen. I put mine on a tray, in a cool room in my basement and enjoy them for weeks after the first fall frost.

Save Ground Cherry Seeds

Each ground cherry fruit is full of many small seeds.

Save and dry ground cherry seed for for the following year. They can stay viable for a few years.

I simply smear some of the seed-filled flesh onto a paper towel. Once it's dry, I put it into an envelope and label it.

Save cape gooseberry seeds in exactly the same way.

Eating Ground Cherries and Cape Gooseberries

Emma shows off a ground-cherry-blueberry crostata she made.

I was once in the Lac St-Jean region of Quebec and found locally made ground cherry liqueur. It was divine—a rich yellow colour, both sweet and tangy.

Fresh ground cherries and cape gooseberries are so tasty that we don't often have a lot left for other uses.

Wondering how to eat ground cherries? There's lots you can do with them:

Ground cherries as garnishes (peel back that papery husk and they look quite attractive!)

Ground cherry jam

Ground cherry cobbler

Ground cherry crostata

Dried ground cherries

Ground Cherry Pests

Three-lined potato beetle larvae enjoying cape gooseberry leaves. Easy to solve with soapy water.

Ground cherries and cape gooseberries are about as trouble-free a crop as you'll get.

If you have a problem, the most common is one of the pests that go after other nightshade crops. They include:

Tomato hornworms

Cutworms

Colorado potato beetle

Three-lined potato beetle

In a home garden, hand pick hornworms and colorado potato beetles. When three-lined potato beetle larvae start making holes in my cape gooseberry leaves, a soapy-water treatment solves the problem.

Prevent cutworm damage by using a newspaper collar around young plants as you transplant them into the garden.

One year a raccoon took a shine to my cape gooseberries...and I'd find empty husks on the ground around the cape gooseberry plants. Toronto has an unusually high density of raccoons, so I don't expect this will be an issue for most people. If it is, a simple solution is to physically exclude the raccoons. Cage the plants. It's what we do with our melons.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

FAQ

Can you grow ground cherries indoors?

There is no need to grow your ground cherry plants indoors, even in a northern climate. That's because you can get a sizeable harvest even where there's a short growing season.

These are nicely branched ground cherry plants. They can get up to about one metre high.

If you really want to grow them indoors (I've never tried) the key would be a light setup suitable for indoor growing. A windowsill over the winter would not be bright enough.

Do ground cherries grow back every year?

The plants die over the winter, but ground cherries often "volunteer," which means new plants grow from seeds left over from prior years.

Are tomatillos and ground cherries the same thing?

No.

Tomatillos (a.k.a. husk tomatoes) produce larger fruit than ground cherries. And unlike ground cherries, the fruit completely fills its husk at maturity, and actually bursts open. While ground cherries are consumed as a sweet, tomatillos are usually picked green for use in savoury dishes.

How many ground cherries do you get per plant?

More than you can count!

How do you overwinter ground cherries?

You don't. Start new plants each spring.

Do ground cherries ripen after picking?

Yes. As the first fall frost approaches, pick green cherries that are almost full size but still green. They will continue to ripen.

More Information About Growing Fruit

Articles

Browse our articles about growing fruit.

Guide to Growing Saskatoon Berries: Planting, Pruning, Care

Courses

Guide to Growing Saskatoon Berries: The Prairie Berry (a.k.a. Juneberry)

Guide to growing saskatoon berries. A Saskatoon bush is a great addition to a home garden…

By Steven Biggs

How to Grow a Saskatoon Bush

As an Ontarian, there was a fruit that I never ate growing up.

But I heard lots about it from Mom.

She grew up in Western Canada, and talked about the saskatoon berries that her parents grew. And when I finally saw a saskatoon bush, on a trip to her childhood home, I was surprised that the row of bushes was taller than me. I'd been expecting something puny, like the wild blueberry bushes we get in Ontario.

What is a Saskatoon Bush?

The saskatoon bush (Amelanchier alnifolia) is a native North American fruiting bush. It has a wide range: Wild saskatoon bushes are found in Alaska and Yukon, and in the harsh conditions of the prairie landscape.

It has a few aliases: South of the border you might hear it called juneberry (june berry), shadbush, and western serviceberry. And in the east, it's sometimes called serviceberry—like it's many kin in the Amelancheier clan. (There are many serviceberry species, some shrubby, some growing as small trees.)

The saskatoon bush (Amelanchier alnifolia) is a native North American fruiting bush.

(If you’ve ever grabbed a handful of wild serviceberries or saskatoons and them spit them out because they’re pithy and dry, it’s time to try the domesticated version! The flavour and texture of the wild berries varies a lot, can comparing them to Saskatoon berries is like comparing a crabapple to a big, red, juicy apple from an orchard.)

Saskatoon Fruit

Ripe saskatoon berries look a bit like blueberries...but the similarities end there. They have a taste of their own, a bit nutty and slightly almond-like.

(In case you’re interested, they’re actually related to apples and mountain ash, so it’s no surprise they’re very different from blueberries.)

The saskatoon fruit turns from green to red as it ripens, with fully ripe fruit eventually turning deep purple—almost black.

Saskatoon Bush Size

Saskatoon bushes can grow to approximately 5 metres (16’) high when not pruned.

But in commercial production, they're often kept shorter, under 1.5 metres (5’) high.

An Ornamental Edible

Along with the attractive fruit, saskatoon bushes have showy spring bloom, with clusters of upright flowers.

Saskatoon bushes are a great addition in an ornamental garden too. Along with the attractive fruit, the spring bloom, with its clusters of upright flowers, is very showy.

In the autumn, the leaves paint the garden with a showy orange colour.

Saskatoon Berries Cold Hardiness

It's as tough as nails! No surprise for a plant that’s native to the Great Plains, it takes harsh, dry conditions.

There are a few things that affect hardiness, but it takes temperatures as cold as -50°C (-58°F), and probably colder.

How to Plant a Saskatoon Berry Bush

Choose a Location

Select a location with a well-drained soil. Saskatoon bushes are tolerant of many soil types. So a clay soil with some soil moisture is fine, as long as the soil is not waterlogged.

Full sun is ideal for the best fruit production. It does respectably well in home gardens with partial shade, although the harvest is less than full-sun locations.

If you get late spring frosts, a sloped location where cold air can drain away is best. South-facing locations in cold areas are not ideal, as they warm up more quickly in early spring. That causes flowering while there's still more risk of frost.

Planting a Saskatoon Shrub

When planting most trees and shrubs it's good practice to keep the depth the same as it was before. Not deeper.

There are exceptions to every rule…and the Saskatoon is an exception.

You can plant your saskatoon bush at the same depth; that's fine. But you can also plant it a bit deeper.

Here’s why:

Saskatoon bushes have a habit of suckering—of sending up new shoots beyond the original bush. The bush gets wider over time, and you can end up with a little Saskatoon thicket!

But when planted a few inches deeper, they're less likely to sucker.

After you've planted, keep it well watered for the first year until it's established. Mulch the soil surface around the bush to control weeds and keep in soil moisture.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Saskatoon Bushes in the Landscape

Saskatoon berries are very versatile in a home landscape.

Here are a few ideas:

Saskatoon Hedge. If it’s an edible hedge you’re after, look no further than the Saskatoon! It’s really ornamental too!

Saskatoons in a Food Forest. In forest gardens, Saskatoons can be grown as shrubs or small trees, and are tolerant of partial shade.

Saskatoon Berries in Containers. Because of their excellent tolerance of harsh conditions, Saskatoon berries are great candidates for container gardens.

I have an edible hedge in my garden that has a saskatoon bush, haskaps, and Nanking cherry.

Find out how to grow an edible hedge.

Check out these 5 types of cherry bushes to grow in an edible landscape.

Saskatoon Berry Care

Pruning Saskatoon Bushes

Regular pruning helps maintain vigour and encourages annual fruit production. (With saskatoon, like many fruit trees and bushes, plants often fruit more heavily every second year, something called biennial bearing.)

With pruning, we're helping the plant grow in a way that's beneficial to us. Importantly, we want to pick saskatoon berries without a ladder! (More fruit within reach means more for you, less for the birds!)

Here are a few more thoughts on pruning your saskatoon bush:

Prune out older, less fruitful wood

Remove diseased branches

The best fruit production is on wood from the previous season (older wood gives some fruit, though not as much)

Some saskatoon shrubs favour one main leading branch (leader) when unpruned. Prune back leaders for a well-branched bush form

Prune when dormant

Remember, prune your saskatoon shrub to control size and to create a multi-stemmed shrub.

With pruning, there are two main types of cut we make:

"Heading" cuts, where we cut a branch back only part way to the main branch they come from, encourage branching

"Thinning" cuts, where we cut right back to the main branch, are used to remove weak or unwanted growth

Feeding and Watering Saskatoon Bushes in a Home Landscape

If you have a well-fed soil that has been amended with lots of organic matter, you might not need to give any additional feed.

Sandy soils don't hold moisture or nutrients as well, so if you're on a sandy soil, be sure to amend the soil with lots of organic matter.

Mature service berry bushes are very hardy and won't require irrigation. While establishing newly planted bushes, water for the first year until well rooted.

When to Harvest Saskatoon Berries

As saskatoon berries ripen, they first turn red or pink. Not all fruit ripen at the same time.

Saskatoons are self-fertile, meaning you get fruit even if you have only one bush. There's no need for a second bush.

Not all flowers open at the same time; and not all fruit ripen at the same time. Fruit on the outside and sunniest part of a bush often develop faster. So expect to pick more than once.

The fruit ripens six to eight weeks after flowering. If you're growing more than one variety, flowering and ripening times vary by variety.

As berries ripen, they first take on a red colour. Next, as they turn to dark purple, you can begin tasting them to figure out if they're close to optimal ripeness. On rip fruit, the flesh is usually pink or red.

How to Use Saskatoon Berries

Our favourite way to use serviceberries is for fresh eating. We graze some in the garden, mix with other fruits for fruit salad, or use them on cereal.

Fresh berries don’t last too long once picked because during picking the skin tears a bit as the stem detaches.

Saskatoon berries go from pink to blue, often to a purple-black colour. Taste some to determine if they’re fully ripe.

Here are a few other ways to use the fruit:

Jams and jellies

Pie

Muffins

Syrup

I've even heard of wine...though I haven't tried it!

And if you want some for using later, freeze them directly in freezer bags—or make some into dried berries.

A few saskatoon berries go nicely atop a crème brûlée! Find out how to make crème brûlée—gardener style!

Propagating a Saskatoon Bush

In the nursery trade, saskatoon bushes are often propagated by cuttings and tissue culture. Sometimes they are seed-grown, but there can be more variability with seed-grown plants.

For home gardeners, rooting saskatoon cuttings is a bit more tricky, as you need controlled conditions.

But its tendency to sucker makes it easy for home gardeners to propagate. The suckers it sends out are from underground stems (called stolons). They shoot up a little way away from the main plant. These can be removed from the parent plant using a spade.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Saskatoon Berries Varieties

Because saskatoon berries are grown as a commercial crop, there are a number of cultivated varieties. You will probably find the best selection at a specialist nursery.

Here are things to look at as you compare saskatoon varieties:

Fruit size

Fruit colour (there are even white-fruited varieties...but they're usually grown as ornamentals)

Bush height and spread

Bloom time

Disease resistance

Pests and Diseases of Saskatoon Shrubs

In a home garden setting pests and diseases are infrequent.

Here are three to watch for:

Rabbits. They enjoy snacking on young branches on new bushes over winter (use tree guards or chicken wire if this might be a problem)

Birds. Don't leave your harvest too late -- and consider netting if birds are likely to be a problem (or just grow more bushes so there's lots to share)

Saskatoon-juniper rust. This disease needs both the juniper and Saskatoon plants to finish its life cycle. It causes raised yellow areas on leaves and misshapen fruit. Cut out the woody galls on juniper that host the disease (you'll see yellow growths on them in spring). If it’s a problem, look for rust-resistant varieties (Arcadia, Broadmoor, Buffalo, Calgary Carpet)

Saskatoon Berry FAQ

What's the botanical name?

Amelanchier alnifolia (Although there are also a couple of cultivars that are hybrids with Amelanchier stolonifera)

How long will a saskatoon shrub live?

With pruning and good care, a saskatoon shrub fruits well for decades, by which point you'll have taken off suckers to make yourself even more plants!

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Course on Home Fruit Growing

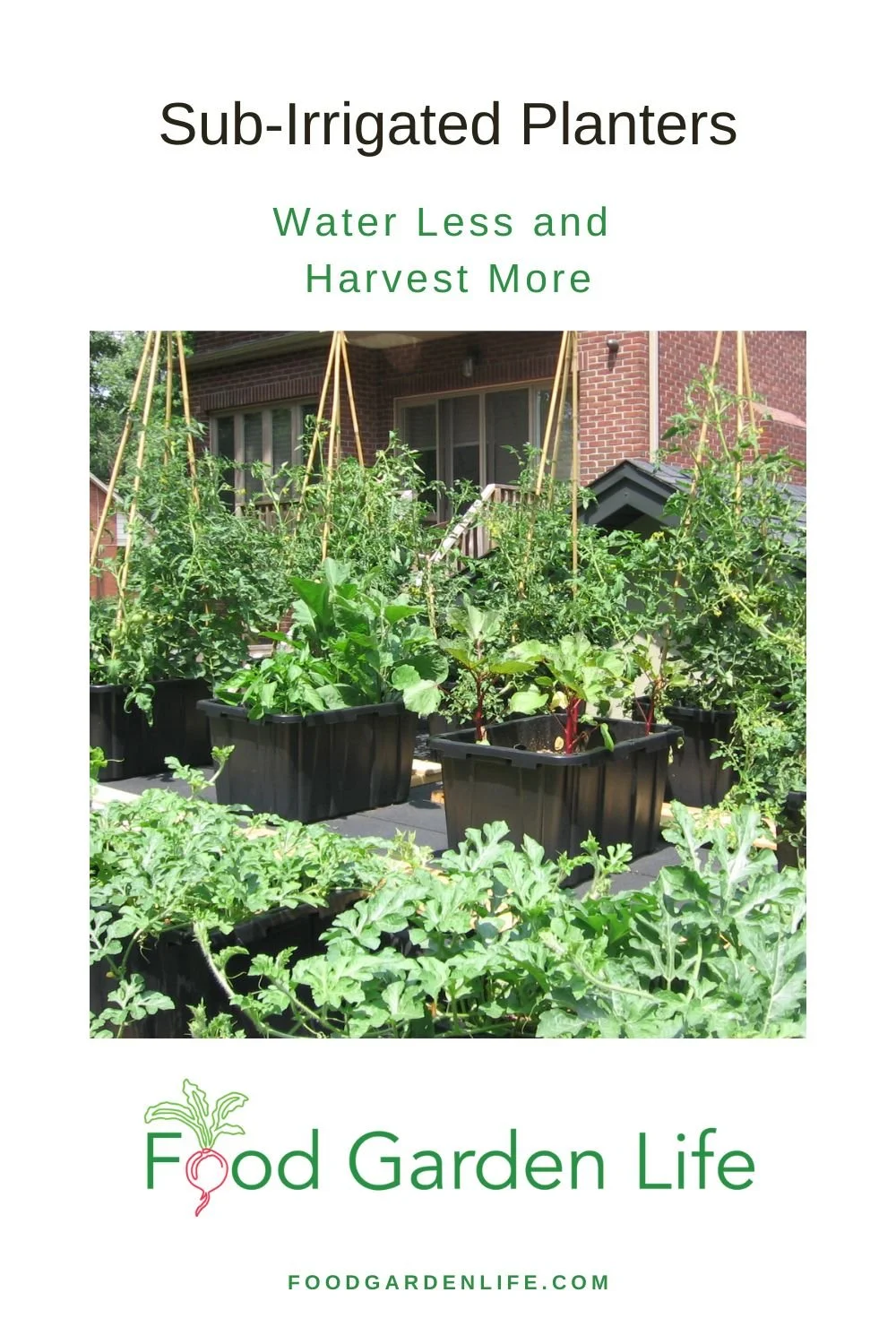

Want to Water Less and Harvest More? Try Sub-Irrigated Planters

Find out how to make your own sub-irrigated planter (a.k.a. self-watering container).

By Steven Biggs

Wilted by Noon

When I first started container gardening on my garage rooftop, I watered every morning. But in the heat of summer, my plants were parched and wilting by noon.

A sub-irrigated planter is an excellent way to solve the problem of parched plants. We want to prevent wilting, because it’s a sign of stress. Drying out is a stress for the crop.

And that stress can delay (or reduce!) your harvest.

Consistent soil moisture is best. Not sopping wet. Not dry.

And that’s where a sub-irrigated planter helps: It keeps the potting mix consistently moist, but not too wet.

This sort of planter is also known as a SIP, a self-watering container, or a self-watering planter.

Keep reading and I’ll explain how a self-watering system works and how you can make your own.

What are Sub-Irrigated Planters?

Sub-irrigation planters are simply planters with a water reservoir at the bottom. The reservoir is right under the soil.

Through capillary action, water wicks up through the potting mix, giving plant roots a consistent supply of moisture. Then, as the plants use water in the soil (creating a moisture gradient) more water wicks upwards from the reservoir.

There are many commercially produced sub-irrigated planters available. Some are fairly basic and resemble a normal container. Others have a gauge that shows the water level in the reservoir.

Self-Watering Planters vs. SIPS vs. Sub-Irrigation Planters

These are all different terms used to describe the same thing: Containers that have a water reservoir below, so that moisture can wick up into the soil.

By the way, they are not truly “self-watering.” The gardener must still fill the reservoir. (If you like do-it-yourself projects, you can automate this with irrigation, see below.)

Benefits of Sub-Irrigated Planters

First, though, let’s look at the benefits of these self-watering containers.

Less waste:

There is less waste of water and fertilizer because it's a closed system, with less runoff

Higher yield because:

A continuously moist growing medium means the plant has no water stress (plant growth can slow, or flowers drop when the plant is under stress…)

When gardening in a container, the growing medium is warmer than soil in the garden, and that means that harvest begins earlier

Fewer weeds because:

The soil surface is not regularly moistened from overhead watering, giving dry surface conditions are not as good for weed seeds to germinate

The other reason that the soil surface is not as wet is that the farther you are from the reservoir, the less moist the soil (remember, it's going against gravity!)

Less disease because:

With no overhead watering, there's less splashing of disease organisms from the potting soil onto the leaves

And with tomatoes, SIPS usually solve blossom end rot (which actually is not a disease, but a physiological disorder that's caused by swings in soil moisture)

And the benefit of a SIP system that goes without saying: You spend less time spend watering!

Where to Grow in a Sub-Irrigated Planter

I made a garden on my garage rooftop using sub-irrigated (self-watering) planters.

As with any sort of container garden, a SIP makes it possible to grow on patios, decks, driveways.

You can also use them to grow over top of areas with tree roots or compacted soil.

If you’ve been eyeing up a space next to that water-hungry cedar hedge, this is your solution!

If you’re concerned about soil contamination, making a container garden is a simple solution.

Find out more about soil contamination.

What’s Inside a SIP

Here's what you'll usually find in a self-watering planter.

A water-tight area (the reservoir) at the base of the container (underneath the potting mix)

Something to hold the potting mix above the reservoir area: it could be a false bottom such as mesh, or hollow containers, or tubing

A way to add water to the reservoir (a fill-tube that extends above the soil surface)

A wick (the wick is usually the potting mix itself, but a fabric wick can be used too)

An overflow hole, so that if there's too much water, it can escape

How a Sub-Irrigation Planter Works

Think of how water moves up a sponge. Or put a piece of paper towel in water and watch the water move upwards.

The same thing happens in a self-watering planter.

The water that's stored in the reservoir moves up through the soil.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Plants That Thrive in Sub-Irrigated Planters

Annual vegetable and herb crops do well in sub-irrigation planters.

Avoid plants that are susceptible to root rot when overwatered. (For example, I grow potted lemon trees, and they hate “wet feet,” soil that says consistently wet. Read more about potted lemon trees.)

Potting Soil for Sub-Irrigated Planters

Choose a potting soil with good wicking properties. Do not use garden top soil or sand.

Sometimes this is easier said than done...because you won't find "wicking" on potting soil labels.

(A bargain isn't always a bargain when it comes to potting soil. If you see discounted bags at big-box retailers, be wary.)

The large compressed bales of potting mix made for commercial growers have a more consistently good quality. If in doubt, start with these.

If you're making your own peat-based potting mix, here’s an important point:

There are different qualities of peat. The darker peat from lower down in a bog is not as good at wicking as the lighter coloured, "blond" peat that comes from the top of a bog. Blond peat isn't always available at garden centres; you might need to go to an outlet that supplies commercial growers to find it.

Make Your Own Sub-Irrigated Planter

It's fairly simple to make your own self-watering planters.

Below is a series of pictures from a batch of planters I made for my garage rooftop garden.

The materials I used were inexpensive, and available at a hardware store:

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric

The tools needed to make these were:

Drill to make overflow hole

Saw or utility knife to cut the weeping tile and dishwasher drain pipe

Scissors to cut the landscape fabric

At the time I made these, I spent about $20 per planter, a fraction of what commercially available self-watering planters cost.

Making a Planter, Step by Step

Supplies to Make a Sub-Irrigated Planter

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric (not shown)

Weeping Tile with Fill Tube

Weeping tile coiled around the bottom of the bin.

A hole cut into the weeping tile with a utility knife allows a piece of dishwasher drain hose to be installed as a fill tube.

Landscape Fabric

The reservoir space created with the weeping tile is covered with landscape fabric so that potting soil doesn’t fill up the weeping tile.

Don’t Forget This!

Drill a drainage hole near the top of the weeping tile.

The hole shown here was too small…and was blocked by a piece of perlite, so i had to drill a bigger hole.

Recycled Items to Make a Self-Watering Planter

I've also made self-watering systems using materials from the recycling bin, or things we already had on hand.

Here are examples of items you can use:

For the Water-Tight Reservoir

Retrofitting a large plastic pot to make a sub-irrigated planter. The reservoir is made from old flower pots, which are covered with wire mesh. The wick (not shown) is fabric. The mesh is covered with landscape fabric so that the potting soil does not fill up the reservoir.

A water-tight container such as a pail

Or, a liner to make a water-tight area in a container with holes (for example, pond liner or construction plastic)

To Hold the Soil Above the Reservoir Area

Drainage pipe

Downspout extenders

Downspouts

Weeping tile

Upside-down flower pots

Landscape fabric, or old t-shirts

For a Fill Tube

Water bottles

Dishwasher drain hose

Pop bottles (“soda” bottles if you’re in the US)

PVC pipe

Retrofit Containers into a Sub-Irrigated Planter

A hypertufa planter with sub-irrigation.

You can retrofit any traditional pot into a sub-irrigation system…even if they have holes in them.

Use a liner to make a water-tight reservoir area at the bottom, and then create an overflow hole.

Planter Maintenance

Potting mixes lose structure over time as the organic matter decomposes. Plan to refresh the potting mix periodically. How often you need to do this depends on the mix, and the conditions. Pay especial attention to the soil in the lower area that acts as a wick.

If you're using a fabric wick, check it annually to see its condition. Fabrics made from natural fibres break down fairly quickly.

Sub-Irrigated Planter FAQ

How deep should a sub-irrigated planter be?

Making a sub-irrigated planter from a smaller, shallower planter. This is perfect for shallow-rooted crops such as leafy greens.

A soil depth of about 30cm (12") is usually lots. Remember, gravity is working against the wicking action...and when the soil is very deep the water doesn't wick all the way to the top.

The larger the plant you’re growing, the larger the volume of soil that you'll need. A smaller container with a 15 cm (6") soil depth can be fine for many smaller crops, such as leafy greens. If you're growing something that gets larger, for example bush-type tomatoes, a larger volume of soil is suitable. (That's why I used the storage bins in the example above. Along with determinate tomatoes, we use them for okra, peppers, and eggplant.)

Can I cover the soil on a self-watering planters?

Plastic mulch over the soil holds in moisture and deters squirrels from digging up transplants in the spring.

Yes. A plastic mulch holds in moisture and stops weed seeds from germinating. There are biodegradable plastic mulches that last for a single growing season.

Lay the mulch over the potting mix, and then tuck it in tight at the sides. Once it's snug, you can cut and X in it with a sharp knife, and then plant into the X.

A springtime challenge for us is squirrels digging up newly transplanted seedlings from our planters. A simple solution is the plastic mulch, which seems to deter digging. (Soil is out of sight, and it’s out of their wee little squirrel minds.)

Or, if you don't like the look of the plastic, burlap works well too. (It's a natural fibre, so doesn't hold in as much moisture, but it deters digging and reduces growth of weed seeds.)

What about watering plants in a SIP from above?

This is fine. It will keep the soil surface moister, so there's more chance of weed seeds germinating. But there's nothing wrong with this...other than it can be much slower than filling using a fill tube.

Can I reuse the soil in my self-watering planter?

Over time, as the organic materials in soil break down, potting soil loses its structure. When is has less structure (fewer bigger particles and fewer air pores) it doesn’t wick as well.

So for best wicking, fresh potting mix work best.

But...replacing potting mix every year is both wasteful and expensive. I usually mix in some new soil mix every year, about 20 per cent.

What is an Earthbox?

It is a well-known brand of sub-irrigated planters.

Is a “global bucket” a sub-irrigated planter?

Yes. I suggest you search online to find out more about this easy-to-make pail-in-pail SIP planter that has a reservoir.

What is a wicking bed?

With a wicking bed, we're taking the same ideas we use in a sub-irrigated planter—just on a larger scale. Now we’re talking about a raised bed. A wicking bed has a water reservoir, fill tube, and overflow just like a SIP does.

If you’re researching wicking beds, you’ll see that the names SIP and wicking bed are often used interchangeably. For me, if it’s a moveable planter, it’s a SIP. If it’s a permanent bed, it’s a wicking bed. But don’t sweat the lingo—as long as you understand how it works inside.

Find out more about wicking beds.

Are there any things to watch for with SIPS?

Yes, salt build-up. Normally, excess salts that can accumulate near the soil surface wash away with watering, and then drain from the bottom of a container. But with a SIP, we’re not washing down salts with water, and any runoff is captured.

That means it's a good practice to flush out your SIPs in the spring. Water heavily from the top, enough to cause lots of water to drain through the overflow holes and carry away excess salts.

How can I automate watering in my self-watering planter?

An irrigation spaghetti tube goes into the fill tube on the SIP.

You can set it up with automatic irrigation that refills the reservoirs.

You want what’s called “spaghetti tubes,” small tubes that run from an irrigation line. One tube goes to each planter. (This sort of system is often used to irrigate container gardens, with “drip emitters” at the end of each spaghetti tube to regulate how much water comes out and onto the soil surface in the container.)

But when you’re setting up spaghetti tubes and drip emitters for a SIP garden, just put the tube and drip emitter right into your fill tube, so that when you turn on the irrigation, you’re replenishing the water in the reservoir—not wetting the soil surface. (That way, less water is lost to evaporation, and you’re not creating conditions suited to weed-seed germination.)

Experience will teach you how long to leave on the water supply to fill up the reservoir.

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Course

Get great ideas for your edible garden in Edible Garden Makeover. Planning. Design. Crops. How-to.

How to Make a Wicking Bed

Harvest more and water less when you grow in a wicking bed. Find out how to make a wicking bed.

By Steven Biggs

Make Your Own Wicking Bed

Harvest more. Water less.

Wicking beds are a great way to maximize the use of space in a small garden. They also save time for busy gardeners.

What’s a Wicking Bed?

A wicking bed is simply raised bed with a reservoir—a water storage area—at the bottom.

They work the same way that sub-irrigation planters (a.k.a. SIPS or “self-watering” pots) work.

Find out more about sub-irrigated planters.

Water wicks upwards from a reservoir below into the soil above through capillary action.

Keep reading to find out how to make a wicking bed.

Less Plant Stress

When plants get thirsty—when there is “water stress”—it can have a big effect on yield.

Because wicking beds prevent water stress, the increase in yield can be considerable. Of course, no one minds the time saved by having to water less frequently.

Even in the heat of summer, when the tomato plants are quite big, we water our wicking beds about once a week.

We turbo-charged our backyard tomato production using wicking beds.

Another Reason to Use a Wicking Bed

Our neighbour’s large black walnut tree is beautiful. But walnut trees give off a compound called “juglone.” And juglone affects the growth of many plants…including tomatoes.

We tried growing tomatoes in the backyard many times…and they always died.

BUT MY DAUGHTER Emma had a vision of a tomato plantation in our backyard, near that walnut tree.

I wondered if we could solve the problem by growing in wicking beds, because the tomato roots would never get into the juglone-contaminated soil below.

It worked—and we now grow tomatoes right under the walnut tree.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Make Your Own Wicking Bed

Be creative with the materials you choose. We decided to use cedar fence posts to make our wicking beds.

Below are photos of wicking beds that I made with my kids using cedar fence posts.

I chose cedar fence posts because they are long-lasting and not much more expensive than dimensional lumber.

Beds made with dimensional lumber often sag outwards over time...and I’m not interested in rebuilding my wicking beds any time soon.

I chose pond liner to create the reservoir because I already had pond liner here.

Be Creative

Be creative! You might want to make a wicking bed from salvaged material—or maybe you want a bed that ties in with the aesthetic in your landscape.

On the practical side, I’ve see wicking beds made from large plastic bins and from recycled lumber.

On the ornamental side, I think red brick would look smashing! One day…

Materials List for My Wicking Bed

Cedar fence posts.

Pond liner. The pond liner holds water in the bottom of the bed. Once the sides of the liner are bent upwards and fixed into place, it creates a shallow water storage area at the bottom of the bed--about as high as the weeping tile.

Weeping tile.

3/4” gravel. Use “clear” gravel, which means that it does not have smaller pieces of gravel that will fill up the spaces in between. That way the space is available to hold water.

Dishwasher drain tube. To create a fill tube.

Landscape fabric. Its purpose is to keep the soil from filling up the piping and the spaces between gravel.

Steps for Making a Wicking Bed

Cut posts to length and notch the ends.

Place notched posts directly on the ground. Level the ground first.

Nail spikes into the corners of the posts to keep them in place.

Install liner at the bottom by placing it on the ground, and up about 8-10 inches at the side. Secure temporarily with staples, to keep it in place until the gravel pins it into place.

Place coils of weeping tile in the bottom. The tile permits water to quickly move through the reservoir, and it also holds up the soil above.

Add gravel. It supports the weight of the soil above, while the spaces between the pieces of gravel fill with water. Water moves upwards through the gravel by capillary action.

Note the fill tube at the far end, a piece of drain hose installed into the weeping tile. This permits filling of the reservoir with a hose after soil has been added.

Cover with landscape fabric to keep soil out of the reservoir area. Note the depressing in the top-right corner: While in theory water wicks up the gravel, I also created this soil-filled wick that dips into the reservoir.

Approximately one foot of soil works well. If there is too much soil, the water will not wick all the way to the top.

Watering my Wicking Beds

I know that there is enough water in the bed as I'm filling it because once the storage area is full of water, I see water coming out of the side of the bed. It's low-tech—but it works.

One More Reason for Wicking Beds

Soil contamination is another reason to consider growing in a wicking bed. Soil contamination can be a concern in areas where there is a history of industry, and also on former orchard lands where sprays with heavy metals might have been used.

Find out more about soil contamination and what to do about it.

Another Way to Add Growing Space in a Small Garden

Straw-bale gardening is a great way to grow on paved areas and areas with poor soil.

Find out more about straw-bale gardening.

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Courses: Edible Gardening

Garden Career Pivot

Thinking about a career in horticulture? Here’s more about the path I’ve taken.

By Steven Biggs

Working in Horticulture

I’ve had a number of readers and students ask about working in horticulture. Some are ready for a career change. Some are thinking about schooling.

But for me, working in horticulture involves going beyond working with plants and soil. It also include the internet and a way of expanding what I can earn in the field of horticulture. Read on to discover what I mean.

(And, yes, snails fit into my own story, as you’ll see below.)

The Great Snail Race

“There is a whole big family of snails I was just getting,” Keaton told me matter-of-factly.

He looked down at them as they moved from his cupped hand onto his shirt. The most daring of the snails was already halfway up his shirt.

But the adventures of the snail family didn’t end with the trek up Keaton’s shirt.

That slow climb up the shirt was just the beginning.

Keaton and the snails.

Next, the snail family sailed across a big puddle on our driveway, on a barely seaworthy scrap of wood. And once they’d sailed to the far side of the puddle, the adventures continued on the slide…with a snail race.

From Rat Race to Snail Race

I cherish that memory. It was a wet walk home from the schoolyard as Keaton collected all those snails.

At the time, my day revolved around walks to and from school. Morning drop-off. Midday drop-off. Afternoon pickup.

It wasn’t all snail races. I was at my desk working before the kids woke up. And between drop-off and pickup I’d snatch moments at my desk whenever I could.

The routine wasn’t something I imagined when I was at my previous job.

The routine was the result of an unwise (but fortunate) decision. I’ll tell you more about that decision in a moment.

But as a result of that decision I was out of the rat race. I was no longer a stressed-out commuter. I enjoyed small pleasures like snail races. And after wanting to quit the city, I was really enjoying city life.

I Started My Garden Work as an Imposter (At Least I Felt Like It)

It was 2006.

Even though the rat race was in the rear-view mirror, I hadn’t quite found myself. At least, I hadn’t convinced myself.

Asked about my profession, I’d hesitatingly respond, “garden and farm writer.” In hindsight, there was no need to hesitate.

My experience checked the right boxes:

I’d been a gardener since I was a kid. As a teen had my own gardening business. As a student I got a degree in agriculture and went straight into the horticulture industry. Check.

And in all of the jobs I’d had along the way, I’d been the person who would put together disparate bits of information into written guides and lists. I get a kick out of sorting and packaging information. Check.

Today

Keaton holding a copy of my first book, No Guff Vegetable Gardening.

My gig today is garden communications. I juggle a few things that relate to gardening and communications. I work as a college instructor, broadcaster, speaker, and writer.

I’ve been honoured to get recognition for my magazine articles, books, and broadcasting. And I was recognized as one of the “green gang” of Canadians making a difference in horticulture.

Most important for me is the flexibility. Almost all of what I do is online. That means I camp with my kids in the summer. If I want to go ice fishing for a day in winter, it’s my call. I can’t not work—but I can weave work around other important parts of my life.

Thinking of a Change?

There’s a need for people in the horticultural industry.

If you’re looking for horticultural work, here are just a few of the roles you can consider:

Landscaping

Landscape design

Greenhouse technician

Retail

Wholesale supplies

Research

Consulting

Here’s a neat apprenticeship option here in Ontario.

Want to grow food? Here’s a neat program near Toronto.

Deciding Who’s the Boss

A lot of people like being an employee: It gives structure and security.

There’s also the option of creating your own work. It’s the path that I followed.

And that brings me back to my unwise decision—the one I mentioned earlier.

How an Unwise Decision Turned Me Into a Garden Writer

My unwise decision was a career change. But I made it for a good reason: Balance.

I was aiming for more family time and less commuting time. To change the balance in my life, I left a job in agricultural marketing to work as a recruiter.

Why as a recruiter?

For no other reason than the office was a bicycle ride from my place. I wanted to be closer to home.

I figured that because I was good at working phones I would be fine in this phone-based work. But there was a problem: I was not good at it…

Months passed. I was still not good at it. Meanwhile, my wife Shelley was just about to wrap up maternity leave, and we weren’t excited about the prospect of daycare. Plus I needed to help my parents more.

It was a collision of life events—not any foresight on my part—that got me to take the leap. The leap from employee to self-employed.

One other thing really helped. An internet connection.

An Internet Connection can be a Gateway

Connecting with work on the internet is easier now than when I started. (I took an HTML coding lesson so I could manage my first website!) Things are much more user-friendly now.

But even though it’s more user friendly, an internet connection or a website or a social media following isn’t a guaranteed income. It’s just a gateway to other people.

So if you’re thinking of creating work, your challenge is to figure out what value you can provide.

First: Take Stock

What are you good at; and what are you not good at?

I suggest you make a checklist for yourself.

For example, my checklist at the time of the great snail race would have looked like this:

Growing food had become a big part of my life — the kind of thing to put on your list as you take stock of your unique experiences

Good on the phone (too much time spent as call-centre slave!)

Not good at being pushy with people

Write well

Can shut up and let people tell me their story (from working on a help desk)

Like to sniff around for leads (from a short career tangent into fraud prevention)

Know how to grow (I’d turned my small urban backyard into a mini farm)

So if you’re thinking of change, stop now and make your own list like this.

Jot down your life experiences. It may seem insignificant; it’s not.

Next: Take Time

As you think about how your different life experiences give you a unique perspective, be open to new ideas.

The final nudge into a garden-focused career arrived when I was on a plane. I unknowingly sat beside an editor for an online magazine. We chatted, and she asked if I wrote…

Then: Grow New Skills

If you want to give people value that they’ll pay for, you might need new skills, or to brush up on skills you have.

In my case, I took night school courses on writing and journalism. Then I joined a garden writer’s association, a farm writer’s association, and a professional writer’s association because I really didn’t know how to go about becoming a “real” writer.

You Might Feel Uncomfortable

I left the house for my first garden writer’s meeting feeling like a fraud. Then I nearly walked out the door when I arrived. It was a sea of grey hair. A bit intimidating for a 30-something. But I met another writer who I then collaborated with to write my first book.

At the first farm writer’s convention I went to, I felt like a misplaced urbanite. But I swapped business cards with an editor, and that led to a decade-long gig writing farm-business articles.

Keep Pivoting

On assignment writing a farm business article, with the kids.

Industries change. Work changes. And your personal needs will change.

When my kids were little I’d pack them up and take them out on assignment to write an article about a farm. We had a few fun adventures.

As they got bigger, I jumped into the topic of gardening with kids, and my daughter Emma and I did videos and books together. (You can see some of that here.)

Now they’re all teenagers. I have my workdays to myself—and I’m blogging and podcasting on a regular schedule. I’ve been honing my interviewing skills, and I love it.

When the pandemic came and people moved to online learning, I pivoted and started teaching my own online gardening courses.

It can feel uncomfortable sometimes, but put yourself outside of your comfort zone.

Set Your Expectations

My daughter Emma signing copies of her book Gardening with Emma.

I see lot’s of online get-rich-quick and passive-income schemes.

My experience is that I can sell something I create when it gives people value and when they want it.

Passive income is an fair goal: After I put the work into a book or online masterclass, there is some passive income from future sales. But there’s also ongoing selling needed. So it’s not entirely passive.

The other thing you’ll want to hash out as you set your expectations is just what you want. This brings me back to the idea of balance.

For me, balance looks like this these days:

Make 3 meals a day for my hungry teenagers

Time with my dad

Time in the garden (so I can write about it)

Write about what I love

Regular garage band practice

No social media apps on my phone

You’ll see my expectations go beyond income-earning activities.

With the expectations I set, I work long days. Some nights I’m teaching until 10 p.m. – then I’m up at 5 a.m. to blog before the morning maelstrom of household teenage emotions puts me in a haze.

Ultimately, the mix you choose should be emotionally and financially sustainable for you. And it should be something that you like enough you can keep doing it. (I’ve had writing assignments that were so painfully mind-numbing that I froze. They weren’t sustainable. I quit those gigs.)

Next Steps

So whether you’re an urban person focused on life balance that includes gardening, or a rural homesteader considering ways to add to the homestead income, here are two questions to start with:

Employee or self-employed

Online work or location-dependent work

As you’re thinking about those questions above, start your creative process:

Take stock of your unique experience and skills

Take time

Grow your skills

Be uncomfortable

Be prepared to pivot

Set your own expectations for success

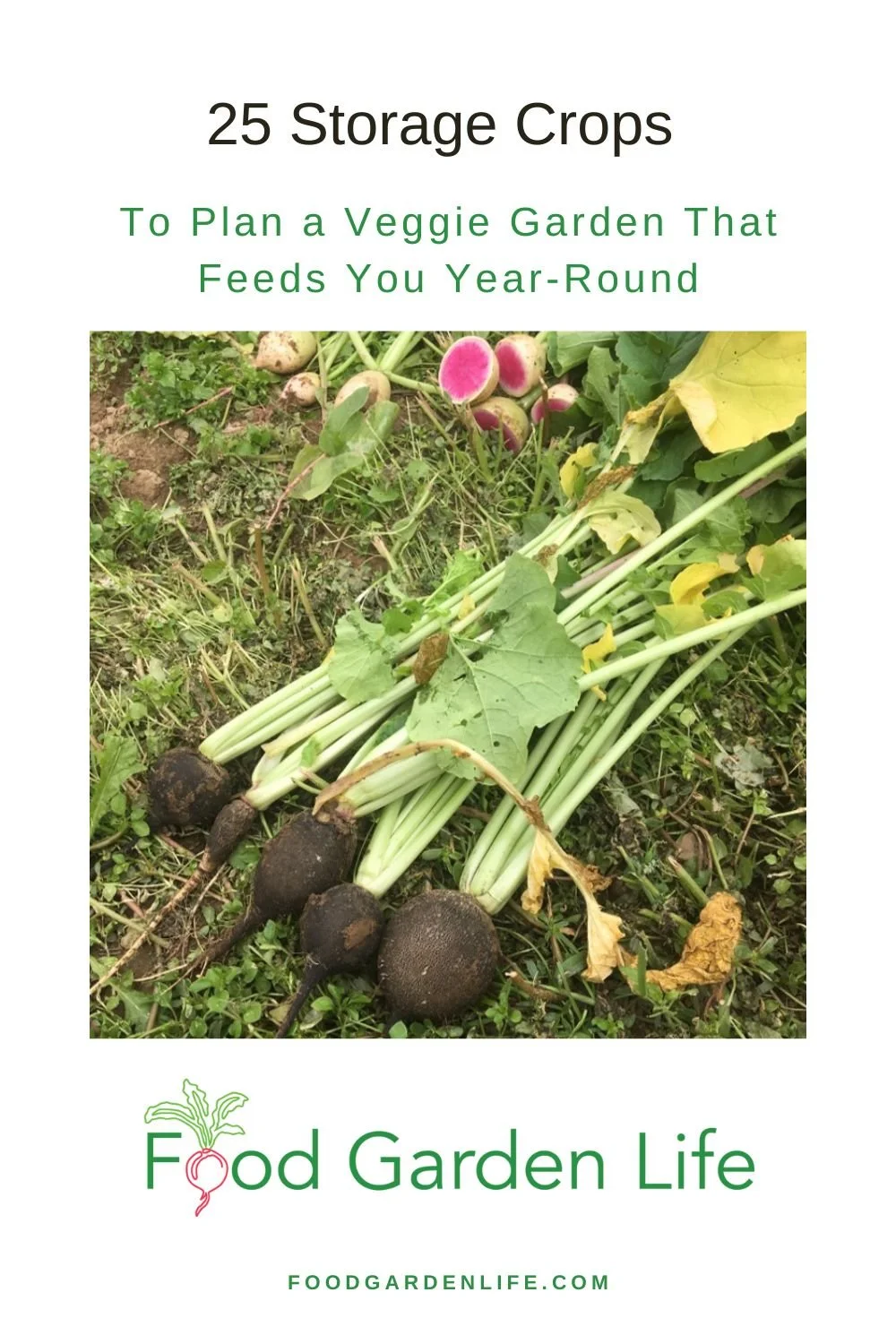

25 Storage Crops to Help You Plan a Vegetable Garden that Feeds You Year-Round

25 storage crop ideas so you can plan a vegetable garden that supplies you with food year-round, even in cold climates, even if you don’t have a greenhouse.

By Steven Biggs

Plan a Vegetable Garden that Includes Storage Crops

I have a plan to turn a room in my basement into a proper root cellar. Braids of onions hanging from the ceiling, homegrown squash on shelves, lots of root vegetables…

But I don’t have a root cellar at the moment.

Maybe it’s the same for you.

The good news is that you can store a lot of homegrown food even if you don’t have a root cellar.

And having lots of vegetables to store starts with your vegetable garden planning. Choose crops that you can store in the garden. And choose crops that store well in protected areas other than a root cellar.

This articles helps you plan a vegetable garden with storage crops in mind.

Storing Crops

I like to think of crop storage two ways. I recommend a bit of each in your vegetable garden plan.

In-Garden Storage: Leave cold-tolerant crops in the garden to continue harvesting as the growing season wraps up.

Harvest and Store: Harvest crops and store in a protected space.

In-Garden Storage

When cool weather arrives, some plants pack it in and die. Think of basil…a little sniff of cold and it drops its leaves in protest.

But some crops do very well in cool temperatures. They soldier on even as fall frosts arrives.

Even with these cold-tolerant crops, growth slows down and stops as days get shorter and shorter. But you can continue harvesting what’s there.

Leafy Greens for In-Garden Storage

Here are my favourite leafy crops for in-garden storage. And to be clear, I’m not suggesting that I harvest any of these winter-long here in Toronto. I don’t. But they have good cold tolerance, and I’ve often picked them from under a dusting of snow.

(If you want to take you year-round harvesting to another level, think of using a combination of cold frames and cold-tolerant crops.)

Kale is very cold-tolerant. If you can only grow one cold-tolerant green, start with kale.

Kale. For cold-climate gardeners, kale is a great season extender. It’s very freeze tolerant. It keeps going as light frosts arrive in the fall. Then as things freeze hard, it still hangs on. I’ve sometimes picked kale in January from under the snow. (The winter-harvested leaves are a far cry from tender, baby kale, by the way. But if you cook it accordingly, it’s a great homegrown addition to the menu.)

Celery. Reliable until hard freezes arrive. (And if you’re thinking celery isn’t a leafy green, you’re right. Except my favourite type of celery is “leaf” celery. Leaf celery, as the name suggests, is more leaf, less stalk—and it’s far less demanding and easier to grow than regular celery.)

Chard. Reliable through those first fall frosts, until hard freezes arrive. Chard also looks great, so if you’re interested in edible ornamental gardens, consider this as you plan your vegetable garden. (Maybe you have ornamental beds that would benefit from a pop of fall colour from one of the many colourful chard varieties.)

Parsley. Reliable until hard freezes arrive. Like chard, also a great ornamental plant. Use it as edging alongside annuals somewhere near your house, so that during muddy fall weather, it’s easy to quickly grab a few sprigs for supper.

Parsley stands up nicely to fall frosts.

A Couple More In-Garden Storage Crops

Keep harvesting cardoon until there’s a hard freeze.

Leek. Like kale, a plant you can keep harvesting into winter. And when there’s a mid-winter thaw, you can go get some more. The leaf tips begin to brown mid-winter…but that’s fine because it’s the lower portion we eat.

Cardoon. Cardoon keeps going through light frosts. It’s leaves wilt, and then spring back up as the day warms. (If you haven’t grown cardoon before, remember to blanch it or it’s horrid…my first forays into cooking cardoon didn’t win me any favours with my family!)

In-Garden Storage Using Straw Bales

As fall frosts arrive, there’s no rush to harvest many of the in-ground root crops. Carrots and parsnips are improved by frost.

A simple way to extend the time you can leave them in the ground is to place a straw bale over top of them. It insulates them and the ground below.

With a heavy mulch, you can leave carrots and parsnips in the ground until the soil freezes solid. Where I am, that’s midwinter. And the longer they’re in the ground, the better they last.

One more thought on leaving roots crops in the garden late: Remember that while carrots and parsnips usually grow under the soil and protected from the first freezes, beet roots often shoulder their way above the soil surface. Those exposed shoulders are quicker to freeze…and that affects the quality.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Harvest-and-Store

First things first: A root cellar is nice…but if you don’t have one, there are other ways to successfully store your harvest. Think about your storage options now, as you plan a vegetable garden. That way you can plant accordingly.

Here are different places you might be able to store your harvest:

Swiss chard with some frost on it. It will spring back up once the sun comes out.

Garage. My garage doesn’t freeze, so I use it to store root crops (and apples that I buy by the bushel…great way to save money). My garage stays just above freezing, and is fairly humid, making is well suited to storing produce.

Clamp. This is a traditional way or insulating harvested root vegetables outdoors, using soil and straw.

Cooler area in a heated basement. I have a room in my basement where I shut off the heat vents. It’s cooler (and darker) than the rest of the house. It’s not as humid or cool as a proper root cellar, but is excellent to store winter squash, garlic, and onions.

Unheated basement. A friend had an unheated basement with an earthen floor…perfect for stored crops!

Sunroom. If you have a sunroom that stays just above freezing through the winter, I’d be thinking about food storage…

Breezeway. Some houses have a minimally heated breezeway between the house and garage. It’s just calling out for food storage!

Attic. If you have an accessible attic, another option for cool storage! The logistics of carrying food up to an attic aren’t ideal, but if it’s all you have, worth a try.

Successfully Storing Crops

Storing crops in the right conditions can really extend the storage life.

Root crops can go into perforated plastic bags, or into moist sand or sawdust in crates. This prevents them from drying out.

Newspaper comes in handy too: cover trays of green tomatoes with a sheet of newspaper; and wrap cabbages in a sheet of newspaper.

Only store unblemished produce. If you have crops that aren’t good enough to store, cook them up or freeze them.

Harvest-and-Store Crops

Dry Bean

When the pods turn light brown, just pull up the entire plant to hang upside-down under cover to dry further. Great storage crop for long-term storage.

Beet

Leave a half inch of stem on the roots as you prepare to store beets. Then they won’t “bleed” as much. Look for varieties recommended for storage. A favourite of mine over the years has been ‘Cylindrda.’

My favourite storage crop! (I make beet borsch with some of mine every year.)

Cabbage

Not a crop that lasts all winter in a root cellar, but you can keep it for a couple of months. The outer leaves dry, and you’ll peel those off as you prep the cabbage for use in the kitchen.

Use midsummer transplants to grow cabbages for winter storage. Harvest as late as possible for storage.

(Don’t forget that you can also use some cabbage to make sauerkraut. Find out how to make your own sauerkraut.)

Cabbage, along with other cole crops such as broccoli, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts are also excellent for in-garden storage as they keep going through early fall frosts.

Carrot

Use midsummer transplants to grow cabbages for winter storage. Harvest as late as possible for storage.

Sweeter after some frost. Look for varieties recommended for storage. ‘Bolero’ is a variety that I like for storage.

Cerleriac (a.k.a. celery root)

Often overlooked, and a great addition for gardeners growing for storage.

Garlic

Easy to grow lots in a small space, and easy to store for gardeners without many storage options, because it and onions like things dryer than the root crops.

Horseradish

As you’re planning your vegetable garden, remember that this is a deep-rooted perennial. So pick a permanent spot for it.

Jerusalem artichoke

A somewhat invasive perennial, so pick a permanent spot for it.

Onion

Braided onions drying before going into storage.

Store onions after curing. Like garlic, important to dry and cure for a couple of weeks before storage. If not properly cured, doesn’t last as long.

You don’t have to braid onions. Another way to store them is to hang them in a mesh bag—so there is good air circulation around the onions.

Parsnip

Sweeter after they go through some frost.

(One year I grew far too many parsnips, and had the brilliant idea of making parsnip wine. Alas, it was horrid…couldn’t even use it as cooking wine.)

Peppers

Often overlooked, but smaller, thin-skinned pepper varieties are easy to dry. Once dry, you can hang them in your storage area, where there’s good air circulation.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Potato

Plan for your storage potatoes to be ready late in the season. During the summer, storage spaces aren’t usually as cool as they are in the fall—so your potatoes can sprout quickly when stored too early.

Don’t put early potato harvests into storage. Plan for a later harvest for storage.

Radish (winter)

So often overlooked, and a great addition in a storage-focused garden.

Root Parsley

Ditto above.

Rutabaga

My mother-in-law’s must-have cooked veg at the Thanksgiving table!

Squash

Pick before light frosts for best storability.

Tomato (keeper)

Keeper tomatoes in the spring.

It’s easy to overlook tomatoes as a storage crop, but there are thick-skinned tomato varieties that can last until spring! They’re called “keeper” or “winter” tomatoes.

These aren’t great for tomato sauce, but are nice chopped into a salad or bruschetta.

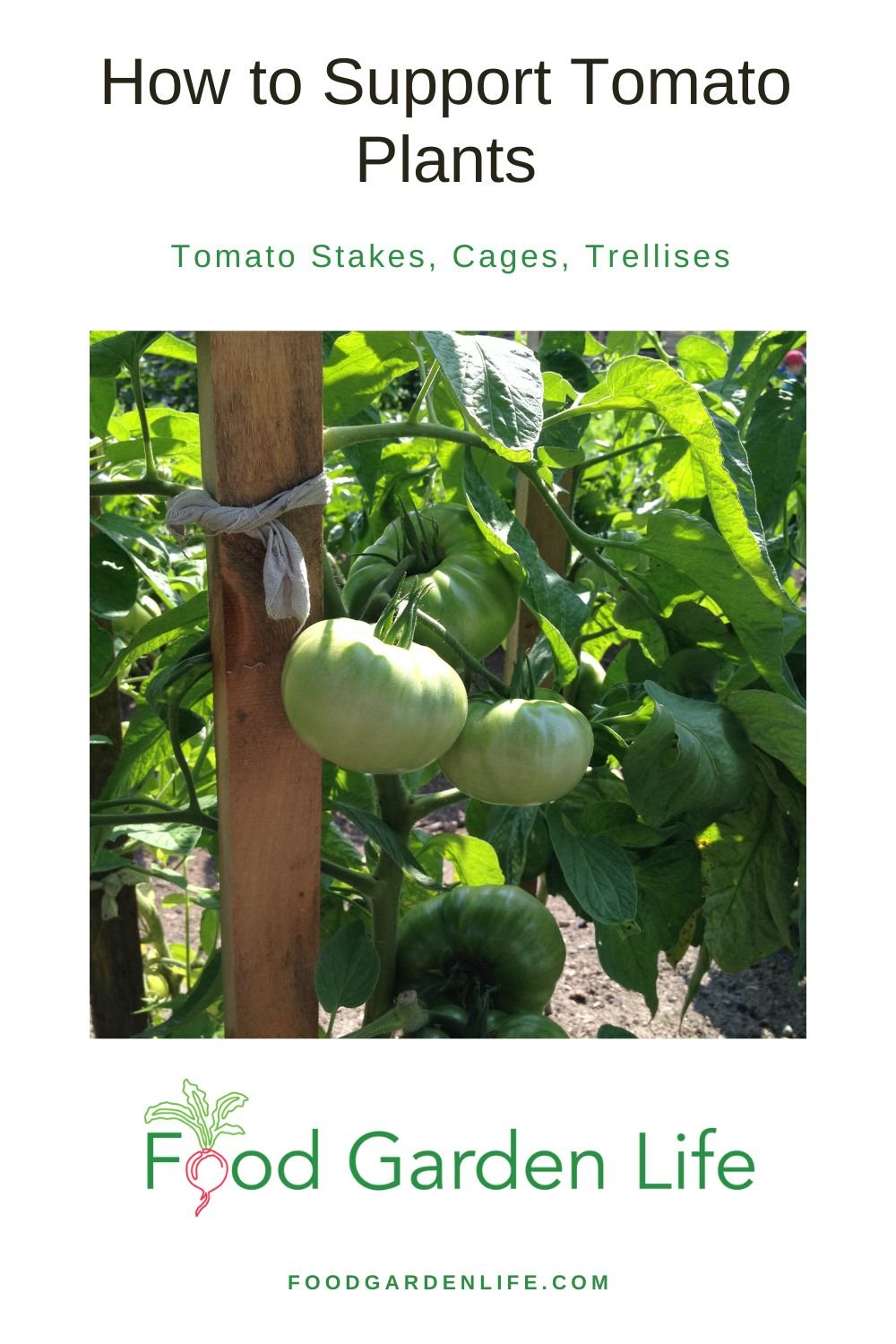

Find out about keeper tomatoes.

Find out my top tips for starting tomato seeds indoors.

Get ideas for different ways to stake tomatoes.

Learn about ripening green tomatoes indoors.

Turnip

A quick-to-mature crop. Remember, the greens are edible too!

Watermelon

Watermelons last a month or so, a nice treat to stow away for a snowy day!

Want Green Veg Over the Winter?

Find out how to grow microgreens indoors.

Need More Ideas to Plan a Vegetable Garden?

Articles and Interviews

Hear an agronomist share top tips for winter vegetable gardening.

7 Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas To Grow More Food In Less Space

Courses on Edible Gardening

5 Types of Cherry Bush to Grow in Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

5 types of cherries to grow as a bush in an edible landscape. Evans cherry, University of Saskatchewan bush cherries, chokecherry, Nanking cherry, Pin cherry

By Steven Biggs

Grow Cherries in an Edible Landscape or Food Forest

A cherry bush is a great addition to an edible landscape or food forest. Here’s a Nanking cherry bush.

The noise!

If you’ve grown cherries, you might have had a flock of birds descend on a cherry tree. Starlings, especially, are so loud that I wonder how they manage to eat and squawk at the same time.

But they do. And they clean out a tree quickly.

The gardener can watch (and listen) – or, go look for a ladder to get up there and compete with the birds for the cherries!

A ladder… Who needs the bother of a ladder in an edible landscape or a food forest?

In a home garden or landscape setting, simplicity is key. Ladders are not simple. Nor are fruit trees that need shaping and regular pruning.

Luckily, there are a number of cherries that grow as bushes.

Some have larger fruit that you can pop right into your mouth. Others, long prized by foragers, have smaller fruit suited for jams, jellies, juices, and wine.

Keep reading for bush cherry crops you can add to your garden.

Benefits of a Cherry Bush vs. a Tree

A bush makes a lot of sense in a home garden or edible landscape.

When you have a bush with multiple stems, you can renew it by lopping of some of the stems so that new stems take over

More branches means more yield

Cherry insurance! (More branches means more chance of some surviving a challenging winter)

Foil the birds…because a bush is easy for you to quickly pick (and easier to net if you’re so inclined)

Cold hardiness, because low-growing branches are insulated by snow

In this article, I have 5 different cherries that you can grow as a bush in your edible landscape or food forest.

These all grow on their own roots (so no grafting required), and are all self-fertile—so you don’t need to worry about growing two varieties to get fruit.

Forget the Ladder…Grow a Cherry Bush

Dwarf Sour Cherry Bushes…from Saskatchewan

The University of Saskatchewan fruit breeding program has produced some great high-yielding hardy bush cherries. (So good that even the BBC wrote about them!)

The bush-like form and the high-quality fruit is the result of breeding Mongolian cherry with European sour cherry.

The bush-cherry cultivars in the University of Saskatchewan “Romance” series have different bloom times, bush size, and fruit colour.

Here are the cultivars:

Carmine Jewel

Romeo

Juliet

Valentine

Cupid

Crimson Passion

Here’s more about the story behind these cherries.

Here’s where you can find out more about ripeness.

Hear bush cherry expert Bob Bors talk about cherry breeding and haskaps at the University of Saskatchewan. https://www.foodgardenlife.com/show/grow-haskap

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Evan’s Cherry in Alberta

Dr. Ieuan Evans with Evans cherries.

Prunus cerasus

When Dr. Ieuan Evans moved to Alberta, he was disappointed to find very few people growing fruit.

But he heard about a very fruitful cherry tree near Edmonton, so he visited – and got pieces of it to propagate. (Just in time, as the property was slated for redevelopment.)

He gave away rooted suckers of this fruitful cherry as fast as he could grow them. It was very cold hardy AND very fruitful.