Wood Ash for the Garden: What You Need to Know

Find out whether wood ash is good for your garden. It can be used as a fertilizer and to make the soil less acidic.

By Steven Biggs

Fireplace Ashes for the Garden?

I have happy memories of cooking holiday roasts over charcoal with my dad. He taught me how to cook over charcoal—and he drilled in the importance of NEVER leaving a barbecue full of ash out in the rain.

Wet ash in a barbecue is like road salt on a car…corrosion just waiting to happen.

Yet many people spread wood ash on the garden.

Actually, sprinkling ash around the yard isn’t anything new. And in an era when people pay attention to how much waste they generate, it seems to make sense not to send wood ash to landfill.

My neighbour Al always sprinkled wood ash around his garden. I’d see the ash as the wind blew it over the fresh snow, and ash specks peppered the sidewalk.

Whether wood ash is good for your vegetable garden depends on your soil and how you’re using the ash.

Thinking further back, I remember as a child, playing on my grandmother’s gravel driveway and eagerly collecting the nuggets of coal clinker from decades before, when ash from the coal furnace was sprinkled around the yard.

But is ash good for the garden? The answer depends on what type of ash it is, how you’re using it, and your soil.

If you’re wondering about using ash in your yard, this post tells you more about wood ash, ways to use it—or when not to use it.

What’s in Wood Ash

Wood ash contains a lot of plant nutrients, including potassium, phosphorus, calcium and magnesium. There are other minor nutrients too.

The amount of the various nutrients in your wood ash depend on the type of wood you’re burning.

The other thing to know is that wood ash is alkaline. So in the same way that lime is used to make soil less acidic, so can wood ash. (More wood ash is needed than lime, though wood ash is faster acting.)

Using Wood Ash in the Garden

Ash has two uses in the garden:

Fertilizing

Reducing the acidity of some types of soil

Whether wood ash is beneficial in your garden depends on soil nutrient levels and soil pH (which is the measure of acidity or alkalinity.)

When soil is too acidic or alkaline, some nutrients get “locked up.” The nutrients might be in the soil—but unavailable to plants. That means:

Ash applied to acidic soils can make more nutrients available by making the soil less acidic (more alkaline)

Ash applied to a soil that’s already alkaline can sometimes make the soil more alkaline to the point that nutrients become unavailable

That’s why you might come across the advice not to use wood ashes on soils with a pH over 6.5.

Don’t Know Your Soil pH?

Pin this post!

Some sources say not to use wood ash in the garden without testing your soil first.

What’s a gardener to do if you don’t want to have the soil tested…but don’t want to unnecessarily send ash to landfill?

I’m not a proponent of soil-testing hypochondria, so I understand. Garden soil is often highly disturbed and highly variable, so one garden bed can be quite different from an adjacent one. (If you guessed that I don’t test my soil, you’re correct.)

Keep reading and get a few ideas.

What to Know About Wood Ash if You Don’t Plan to Test the Soil

Like many things in life, moderation is key.

Soils with high levels of organic matter and clay can resist pH change—so the occasional sprinkle of ash isn’t a problem. I sprinkle some wood ash the slightly alkaline clay soil in my vegetable garden; it’s got lots of organic matter, and I don’t put on a lot of wood ash.

You can also sprinkle in ash as you add new layers to the compost heap. The organic matter in the compost absorbs the nutrients so they’re not washed away. Organic matter also lessens the change to pH.

Using Wood Ash in the Garden

If you’re using wood ash in the garden, remember that it’s not a complete fertilizer. It doesn’t have any nitrogen, for example.

Here are tips for using wood ash in the garden:

On bare soil, sprinkle on wood ash at least a couple of weeks before planting, and then rake or dig it into the soil.

If applying wood ash to the soil and you don’t want coarse bits, sift out big unburnt chunks (hardwire cloth works well, though you can skip this step if you’re putting your wood ash in the compost)

On bare soil, sprinkle on wood ash at least a couple of weeks before planting—but not too far ahead because it’s soluble and nutrients will wash away

Rake or dig in the wood ash—you don’t want to seed into ash, and mixing with soil at least a couple of weeks beforehand gives it time to start breaking down

Don’t apply wood ash near germinating seeds, because they can be easily damaged by the high salt levels.

Don’t overdo it…keep it to once per year because too much wood ash (or too much of many fertilizers) can make some nutrients unavailable to plants

Use only wood ash. Don’t use ash from cardboard, briquettes, pressure-treated timber, or painted woods.

If you heat with only wood, you might find you have more ash than you have garden to spread it around. Don’t make heavy, repeated applications in the same part of the garden. Consider spreading some over the lawn, or sprinkling in some with new additions to the compost pile.

Your acid-loving plants such as blueberries, raspberries, azaleas, and rhododendrons won’t appreciate ash treatments. Skip these plants, even if you have an acidic soil. (And potatoes too, because alkaline conditions encourage the disease potato scab.)

Types of Wood Ash

Ash from wood burned in stoves, fireplaces, and outdoor fire pits is suitable. So is ash from hardwood lump charcoal.

Stick to wood ash: Ash produced from cardboard, coal, briquettes, pressure-treated wood, and painted woods can contain stuff we don’t want in the garden, including heavy metals.

Storing Wood Ash

Keep wood ash dry until you use it.

The potassium in wood ash is soluble, meaning it leaches out with rain. So keep the wood ash dry until you’re ready to use it in the garden.

Other Wood Ash Uses

Wood ash has long been used to make lye for soap. I don’t make my own soap, but I do use wood ash to clean the windows of my wood stove. I dip scrunched up newspaper in water, and then into wood ash before rubbing it on the glass. It’s an excellent glass cleaner.

Wood ash is caustic, meaning don’t breathe it in, and mind your skin and eyes.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Soils

Soil and composting Articles and Interviews

For more posts about how to grow vegetables and kitchen garden design, head over to the soil and compost home page.

Edible Gardening Courses

Want more ideas to make a great kitchen garden? We have great online classes that you can work through at your own pace.

How to Make a Wicking Bed

Harvest more and water less when you grow in a wicking bed. Find out how to make a wicking bed.

By Steven Biggs

Make Your Own Wicking Bed

Harvest more. Water less.

Wicking beds are a great way to maximize the use of space in a small garden. They also save time for busy gardeners.

What’s a Wicking Bed?

A wicking bed is simply raised bed with a reservoir—a water storage area—at the bottom.

They work the same way that sub-irrigation planters (a.k.a. SIPS or “self-watering” pots) work.

Find out more about sub-irrigated planters.

Water wicks upwards from a reservoir below into the soil above through capillary action.

Keep reading to find out how to make a wicking bed.

Less Plant Stress

When plants get thirsty—when there is “water stress”—it can have a big effect on yield.

Because wicking beds prevent water stress, the increase in yield can be considerable. Of course, no one minds the time saved by having to water less frequently.

Even in the heat of summer, when the tomato plants are quite big, we water our wicking beds about once a week.

We turbo-charged our backyard tomato production using wicking beds.

Another Reason to Use a Wicking Bed

Our neighbour’s large black walnut tree is beautiful. But walnut trees give off a compound called “juglone.” And juglone affects the growth of many plants…including tomatoes.

We tried growing tomatoes in the backyard many times…and they always died.

BUT MY DAUGHTER Emma had a vision of a tomato plantation in our backyard, near that walnut tree.

I wondered if we could solve the problem by growing in wicking beds, because the tomato roots would never get into the juglone-contaminated soil below.

It worked—and we now grow tomatoes right under the walnut tree.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Make Your Own Wicking Bed

Be creative with the materials you choose. We decided to use cedar fence posts to make our wicking beds.

Below are photos of wicking beds that I made with my kids using cedar fence posts.

I chose cedar fence posts because they are long-lasting and not much more expensive than dimensional lumber.

Beds made with dimensional lumber often sag outwards over time...and I’m not interested in rebuilding my wicking beds any time soon.

I chose pond liner to create the reservoir because I already had pond liner here.

Be Creative

Be creative! You might want to make a wicking bed from salvaged material—or maybe you want a bed that ties in with the aesthetic in your landscape.

On the practical side, I’ve see wicking beds made from large plastic bins and from recycled lumber.

On the ornamental side, I think red brick would look smashing! One day…

Materials List for My Wicking Bed

Cedar fence posts.

Pond liner. The pond liner holds water in the bottom of the bed. Once the sides of the liner are bent upwards and fixed into place, it creates a shallow water storage area at the bottom of the bed--about as high as the weeping tile.

Weeping tile.

3/4” gravel. Use “clear” gravel, which means that it does not have smaller pieces of gravel that will fill up the spaces in between. That way the space is available to hold water.

Dishwasher drain tube. To create a fill tube.

Landscape fabric. Its purpose is to keep the soil from filling up the piping and the spaces between gravel.

Steps for Making a Wicking Bed

Cut posts to length and notch the ends.

Place notched posts directly on the ground. Level the ground first.

Nail spikes into the corners of the posts to keep them in place.

Install liner at the bottom by placing it on the ground, and up about 8-10 inches at the side. Secure temporarily with staples, to keep it in place until the gravel pins it into place.

Place coils of weeping tile in the bottom. The tile permits water to quickly move through the reservoir, and it also holds up the soil above.

Add gravel. It supports the weight of the soil above, while the spaces between the pieces of gravel fill with water. Water moves upwards through the gravel by capillary action.

Note the fill tube at the far end, a piece of drain hose installed into the weeping tile. This permits filling of the reservoir with a hose after soil has been added.

Cover with landscape fabric to keep soil out of the reservoir area. Note the depressing in the top-right corner: While in theory water wicks up the gravel, I also created this soil-filled wick that dips into the reservoir.

Approximately one foot of soil works well. If there is too much soil, the water will not wick all the way to the top.

Watering my Wicking Beds

I know that there is enough water in the bed as I'm filling it because once the storage area is full of water, I see water coming out of the side of the bed. It's low-tech—but it works.

One More Reason for Wicking Beds

Soil contamination is another reason to consider growing in a wicking bed. Soil contamination can be a concern in areas where there is a history of industry, and also on former orchard lands where sprays with heavy metals might have been used.

Find out more about soil contamination and what to do about it.

Another Way to Add Growing Space in a Small Garden

Straw-bale gardening is a great way to grow on paved areas and areas with poor soil.

Find out more about straw-bale gardening.

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Courses: Edible Gardening

Grow Vegetables in Straw Bales

Straw bale vegetable gardening is an easy way to create more growing space.

By Steven Biggs

Make More Growing Space with Straw Bale Gardens

I started straw bale gardening to solve a problem.

The problem? We needed more growing space for my daughter Emma’s 100-plus tomato varieties.

We have a big yard for the city. But there’s a black walnut tree that makes much of the yard unsuited to growing tomatoes.

(That’s because black walnuts give off a compound that kills the tomato plants…and a number of other plants too.)

With a long and ugly driveway that could fit a couple of school buses, Emma and I began to imagine a tomato plantation on the driveway.

In this post I’ll talk about how to use straw bales to make gardens on paved areas or over soil that’s not great for gardening.

Straw Bale Driveway Garden

Straw bales are an easy way to create a near-instant garden on paved surfaces and areas with poor soil. That’s because the straw bale is both the growing medium and the container.

Here’s how it works: As the straw bale decomposes, it creates an ideal growing medium that is well aerated and holds lots of moisture. It’s like a big sponge. It’s perfect for plant roots – better than many garden and container soils.

In short, you’re composting a bale of straw, and growing your vegetable plants in it at the same time.

Straw Bale Gardening: Top Tip

Our straw bale driveway garden

The most important thing to remember is that bales should be “conditioned” before you grow in them.

Conditioning means kick starting the microbial action. And you know when it’s working because as the microbes start to break down the straw, the temperature inside the bale goes up. We don’t plant in it yet…it might be too warm for our plants.

As the temperature comes down, your bale is ready to plant. Some people use a thermometer. I stick in my finger. It’s not an exact thing.

I allow 3-4 weeks for this conditioning process. It might be less if you’re somewhere warmer than me.

Since the bales in our driveway garden are for heat-loving tomato plants that we put out in late May, we start conditioning the bales late-April to make sure they’re ready for the planting date. I just work back four weeks from my planting date.

Straw Bale Garden Setup

Emma conditioning the newly arrived straw bales.

Before your bales become heavy from watering them, it’s a good time to think about how you want to arrange them. There’s no right or wrong, it depends on your situation:

If you’re planning to use a long soaker hose, you might want them in a long line.

If you’re gardening with kids, arranging them in a square makes for a nice hidoute once the plants get bigger

If you’re watering with a hose, arrange the bales so you can easily move amongst the bales with the hose

How to Orient Straw Bales

Once you know how you want to arrange the bales, think about how you’re orienting them. You can place them so that the loops of twine are on the top and bottom – or the twine is at the sides. Both ways of orienting the bales are fine.

But here’s how I do it: When positioned so that the twine is at the sides, the straw within is mainly oriented vertically. Bales positioned this way absorb more water, so it’s less likely to run off of the side of the bale.

How to Condition Straw Bales

To condition the bales – which just means getting the microbes working – we need 2 things:

Water

Nitrogen

In this picture the bales are oriented with the twine at the top and bottom of the bales. We now prefer to have the twine at the side for easier water penetration.

Place a nitrogen source on top of the bales and water well. The goal is for the water to soak into the bale and move some of the nitrogen into the bale. Use a low pressure and volume so that water doesn’t flow over the sides of the bale (and take the nitrogen with it).

More on the nitrogen source: When you’re looking at the numbers in the fertilizer formulation, you want the first number, the nitrogen, to be higher than the others. For example, blood meal is 12-0-0. That’s what I usually use.

Other years I’ve also used a high-nitrogen organic fertilizer derived from guano, and a lawn fertilizer.

Here’s how I condition straw bales with blood meal:

I water well every day for the first week.

Starting on the first day, and again every other day, I put a 2 cups of blood meal on the bale BEFORE watering (so the water moves some of the blood meal into the bale).

I give 3 applications of blood meal.

As we get into week 2, the bale should be warming up nicely inside!

After 2 weeks, fertilize the bales with a balanced, all-purpose fertilizer.

During this conditioning process, the temperature can go up to about 50°C (120°F), and then it drops. You can plant in the straw bales once the temperature has dropped below about 26°C (80°F)

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Straw-bale Garden Plant Layout

Plant densely to make the best use of space in your straw bale garden.

Wondering about plant spacing in a straw-bale garden? Because a well-managed straw bale garden provides plants lots of moisture and an excellent growing medium, you can plant densely.

We aim for two or three tomato plants per bale. Around those tomatoes we sow bush beans and leafy greens.

Something else to think about with straw bales is that you can plant into the side of the bale too. We’ve grown dwarf tomato plants out the side of bales, while at the top are normal determinate and indeterminate varieties.

How to Support Plants in Straw Bale Gardens

Because there is a paved surface below, and because the bales decompose and start to collapse over the summer, regular staking is not an option.

Here’s what I do instead of staking:

Use 3-4 stakes positioned over the bale to create a self-supporting tee-pee.

Put the bales next to a fence and grow vining crops up the fence.

Looking for tomato-staking ideas? Find out how to stake and support tomato plants.

Straw Bale Garden Planting and Care

How to Plant in Straw Bales

When I show pictures of straw bale gardens to groups, I’m asked where the soil is. There doesn’t have to be soil, because the straw is the growing medium.

When transplanting, use a trowel to pry an opening into the bale. Then place the transplant into the opening, and close up the opening. Be sure to cover the transplant roots with straw so they remain moist.

With large seeds like beans, we just insert them right into the bale. Again, no soil necessary.

When direct seeding smaller seeds onto a straw bale, a thin layer of soil is helpful. We add about an inch of soil over the top of the bale if we’re seeding leafy greens. Use a potting soil or good garden soil that won’t cake with frequent watering.

Straw Bale Garden Fertilizer and Water

Once your bales are conditioned and planted, feed with a balanced, all-purpose feed and keep them well watered. Because the inside of the bale remains well aerated, excess water is not likely to harm the plants. But excess water will wash away nutrients.

If there are not many bales in your garden, hand watering might be fine.

For larger gardens, drip irrigation or a soaker hose works well. Position the soaker hose to sprays downwards, into the bale.

Grasses and Mushrooms on Straw Bales

It’s normal to get mushrooms growing on straw bales. It means you’ve created good growing condtions.

Don’t be surprised to see little grass-like plants and mushrooms growing on the bales. These are good – it means you’ve created good growing conditions.

The grasses are any residual grain within the bale that germinates and grows. They won’t out-compete your crops. Just pull them off.

Straw Bale FAQ

What do you do with Straw Bales After Harvest?

After a year of growing I use the straw to mulch gardens, on pathways, and in my compost pile.

How Many Years do Straw Bales Last?

I’ve sometimes used bales a second year. How fast a bale decomposes varies with your weather conditions. Friends in warmer areas report that one year is the maximum for them.

What if the Twine Breaks?

Broken bales? No problem. In this straw bale garden the tall sections are tomato cages filled with loose straw from broken bales.

If possible, tie it back together; or use a new, longer piece of twine to tie together the bale. If that doesn’t work, you can pack straw into a cage or pot instead.

As you carry the straw bales, try to do it in such a way that the twine does not slide off the side of the bale.

Do Straw Bales Leave Marks?

Yes. Straw bales can darken paved surfaces.

I don’t recommend using them on wood because it creates conditions that could speed up the decay of the wood.

One year I had them against a board fence, and it resulted in dark marks on the fence – so I now position the bales a couple of inches away from the fence.

What About Hay Bales?

Hay bales can also make an excellent growing medium, but there are a couple of reasons they’re not used as frequently as straw bales:

Hay often includes lots of grass seed – not something you want to introduce to your garden

Hay is often more expensive than straw

What are the Best Plants for the Straw-Bale Gardening method?

You can grow a wide range of vegetable crops in straw bales.

Heat-loving crops benefit from the warm root zone in the bales

Root crops develop very well in the well-aerated growing medium

Leafy greens grow well and can be planted underneath other crops such as tomatoes

Cascading plants such as nasturtiums (for edible flowers!) can drape down over the side of the bales

Where can I Buy Straw Bales?

Straw bales are fun for kids.

I used to bring home loads of bales in my minivan. And my family hated all the prickly little bits of straw it left everywhere. So now I just get straw delivered.

To find a farmer, use an online classified advertising website.

And if you have kids: Get straw bales earlier than you need them – for your kids. Straw bales are like giant, biodegradable Lego blocks.

Don’t Straw Bales attract Rats?

The mention of straw has some people wondering whether straw bale gardens will be overrun with rats.

It’s a good question. Not in my experience.

The thing to remember with rats and mice is that they’re looking for food, shelter, and water.

A bale on a paved surface doesn’t give them burrowing room. Doesn’t give them water. Doesn’t give them much food.

What’s more likely to attract rats is bird baths, bird feeders, leaving out pet food, and improperly stored garbage. (On that note, gardening itself, and growing plants with seeds and fruit that are food for rodents, attracts rats.) Remember too, that they’re already abundant in many areas – just not out and about at times that we see them.

More Vegetable Garden Techniques

Home Garden Soil Contamination

By Steven Biggs

Understanding the Risk of Soil Contamination Around Your Home

AFTER MOVING INTO MY WORLD WAR I-ERA HOUSE, I decided to find out if the paint-chip-studded soil next to the house was safe for growing edible crops.

Many pre-1991 paints contained lead, and those that are pre-1960s—particularly exterior paints—are thought to be the worst culprits.

Lead was also used as a gasoline additive into the 1990s. So urban areas with older buildings, where there have been years of car exhaust—and maybe even industrial emissions—tend to have higher soil lead levels than rural, agricultural areas.

With this in mind, I wanted to understand what, if any, risk lay hidden in my soil.

If you’ve wondered what, if anything, to check with the soil in your garden, keep reading for a practical way to approach soil contamination.

Conflicting Information

With an older house, I was worried about lead contamination from paint.

The more I delved into the question of urban soil contamination, the less clear the issue became.

I found a government fact sheet saying there was minimal risk to consuming veggies grown in soil with lead levels below 200 parts per million (ppm)

But one from another jurisdiction advising 300 ppm.

Both noted increased risk for children (think soil moving hand to mouth), in which case one gave a safe upper limit of 100 ppm.

I was left wondering whether I should go with 100, 200 or 300 ppm.

So I Got on the Phone

When I called Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment, I was told that contaminant levels in typical agricultural soil are often less than urban areas, but there should be no concern as long as the readings for my soil fell below the residential standards, as set out in the provincial Environmental Protection Act.

But…I should also keep in mind that a reading above that residential level isn’t necessarily unsafe.

Understanding soil contamination was starting to seem as fun as doing my tax return.

So, after scanning the Act, I added 45 ppm lead (for typical agricultural soil), 120 ppm lead (for residential standards), and a big question mark (for “isn’t necessarily unsafe”) to my growing list of values.

This was getting to be as much fun as preparing a tax return!

And just as filling in a tax return isn’t black and white—think of deciding what’s tax deductible and what’s not—I sensed balancing soil contamination and growing edibles had shades of grey, too.

So I set out to see how urban veggie growers can best tackle the question of soil contamination without being mired in conflicting numbers.

What Other Growers Do

Travis Kennedy, an agrologist involved in community garden projects, also raises produce at his Lactuca Micro Farm in Edmonton. “Pragmaculture,” he responds with a laugh, when I ask how he deals with possible soil contamination. His pragmatic approach to urban agriculture is to always use raised beds, bringing in soil he knows is safe, because he always assumes that there may be contamination.

Ward Teulon, also an agrologist, runs City Farm Boy in Vancouver, designing and building vegetable gardens. Teulon explains that sending backyard soil samples to a laboratory doesn’t always give a clear picture of what’s in the soil because urban soils are moved around a lot and are not uniform. He agrees, however, that interpreting results from expensive tests, which can cost hundreds of dollars, can be daunting. If there is a cause for concern, he believes money is better spent bringing in soil to make a raised bed. “Find out your property’s history,” he advises, because many urban soils are perfectly fine.

Luckily for me, my property’s history seems clear-cut, from agricultural to residential.

So, aside from the paint-chip-infested soil beside the house, I’m not worried. Gardeners who don’t know the history of their site could ask neighbours about past use and nearby properties, or check municipal records or archives.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Asssessing the Risk

In 2014, Toronto Public Health created a plain-language guide to help gardeners understand the issues surrounding possible soil contamination and growing edibles.

Josephine Archbold, who helped write the Guide for Soil Testing in Urban Gardens, says it’s wrong to think only experts can figure out when to grow and when to worry.

The guide moves away from the notion that soil is either safe or unsafe—a black-and-white approach.

“I think we need to move beyond the concept of ‘safe’ and ‘not-safe’ cut-off levels that tell gardeners to either garden (100 per cent) or not garden at all (0 per cent),” she says. Instead, the guide is intended to help gardeners think about the risk of contamination for a site, and gives options to deal with the situation. Testing is expensive, and raised beds can be expensive, too, so the guide encourages taking such actions only when the risk of contamination makes them appropriate.

Three-Step Guide

Step 1

Former orchard land is among those sites considered medium concern because of the legacy of old metal-containing sprays.

In the three-step guide, the first step is to establish a level of concern by looking at former land use. With high-concern sites (e.g., former gas stations), contamination is very likely, so the guide recommends skipping expensive tests and using risk-minimizing measures such as raised beds, container gardening, or cultivating fruit and nut trees—for which contaminant uptake isn’t a concern. Nor is soil testing recommended for low-risk sites (e.g., long-term residential areas).

There are medium-concern situations (e.g., hydro corridors and former commercial land) where testing is recommended, but even then, if gardens are smaller than 170 square feet (16 sq. m), raised beds are suggested because the cost of raised beds for such a surface area is likely less than testing. Surprisingly, former orchard land is among those sites considered medium concern because of the legacy of old metal-containing sprays.

After investigating the history of the garden site, another part of establishing a level of concern is physically inspecting soil: dig in a few random spots to see if there are unusual stains or odours, and note old equipment, tanks and debris that might provide clues to dumping. Dumping, burning, smells and staining can make for a high-concern site.

Step 2

When it comes to step two, testing the soil, the guide lists common contaminants, including some metals (such as lead, arsenic and cadmium), along with PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), which Archbold explains are compounds that indicate past industrial activity. “Our soil screening values are specifically for urban gardening,” she says.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Step 3

The third step is to take actions to reduce risk. In keeping with the guide’s approach, the screening values don’t tell gardeners to either garden or not garden. The values help guide the actions of gardeners. For example, if test results or site history present a medium concern, suggested tactics are lowering the level of contaminants by adding clean soil and organic matter. Archbold says adding organic matter makes many contaminants less mobile.

Another example of how to reduce risk is reducing soil dust by covering soil with a mulch, peeling root vegetables before eating and avoiding crops more likely to accumulate contaminants (cabbage family, beets and spinach).

Suspect Contamination?

If you suspect contamination and opt for testing instead of raised beds, containers, or fruit and nut trees, the guide gives pointers about how to find an accredited lab in your area. When collecting soil samples, there are some important steps to follow—and the guide gives instructions for this as well.

As for the strip beside my house, I will plant a fruit tree. I still don’t know how many parts per million lead are in the soil there, but because the site inspection (namely, digging and seeing all those paint chips) points to a possibility of contamination, my guess is that lead levels could be on the high side. It’s a very small space, so I’ve ruled out expensive testing.

I’ve also ruled out a raised bed because I don’t want to redirect water into my neighbour’s yard. So, a fruit tree seems to me to be the most practical approach—and is an acceptable shade of grey for me.

Originally published in Garden Making Magazine, Spring 2014

More Food Gardening Ideas

Library of Articles

Courses

What to do with Pumpkins After Halloween (and a Pumpkin Recipe!)

By Steven Biggs

Cook (or Compost) Your Pumpkins Too!

The first pumpkin is carved for Halloween this year; the kids had a pumpkin-carving get-together with friends over the weekend. That only leaves three giant pumpkins, four pie pumpkins, a warty pumpkin, a Jamaican pumpkin, a Turk’s turban squash, a blue hubbard squash, and an elongated pinkish pumpkin. Guess what we’re doing tomorrow!

We’ve hit a pumpkin-carving crescendo this year. The kids are the right age to design and carve. I love it as much as my they do. (To my imagination that blue hubbard squash looks a bit like a turkey in a roasting pan…)

Did we go overboard with so many pumpkins and squash? No.

Pumpkins make their way into our kitchen, or into our soil. We eat them or compost them.

Pumpkin Muffins

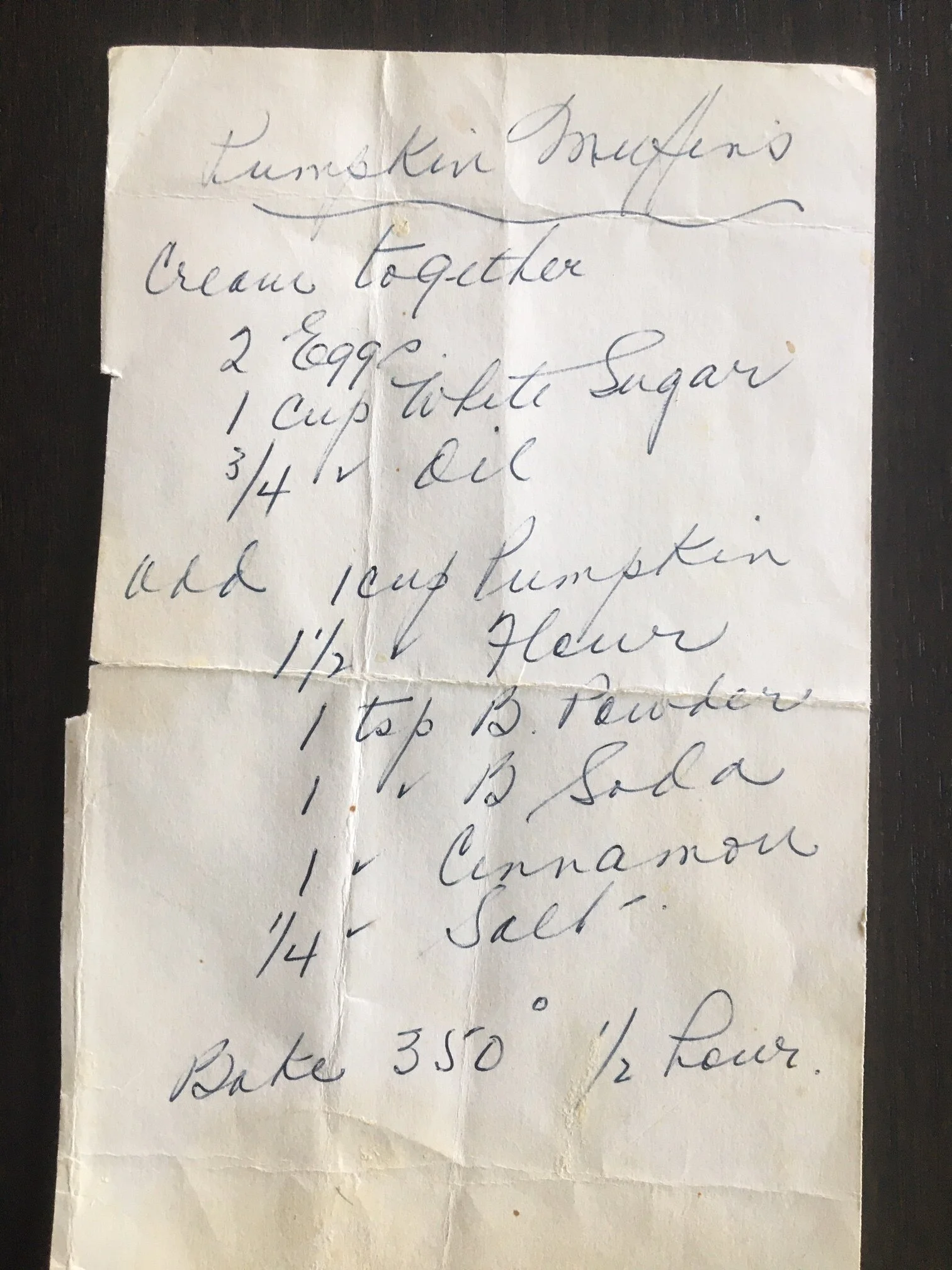

Nana Biggs’ pumpkin muffin recipe. (I usually cut the sugar in half and add raisins and nuts.)

One of Nana Biggs’ favourite recipes was pumpkin muffins. I remember as a kid taking my jack-o-lantern there the day after Halloween so that Nana could roast it.

(My Uncle Bill didn’t agree with my giving Nana all of that pumpkin as he didn’t care for the supply of muffins encouraged by it. I never let him forget that. One fall after I had moved away from home, I roasted a jack-o-lantern, baked a giant, six-inch-wide muffin, and sent it to Uncle Bill by courier.)

My kids all like pumpkin muffins, so Nana would be pleased. They love roasted pumpkin seeds too. (A bit of oil, salt, and garlic powder makes a mean roasted pumpkin seed, in my opinion.)

Last year, my wife, Shelley, spent a whole day roasting various pumpkins and squash, and made a series of pies, using different proportions of each. We got to taste-test them all. There were lots more that went into the freezer. We just ate the last one yesterday.

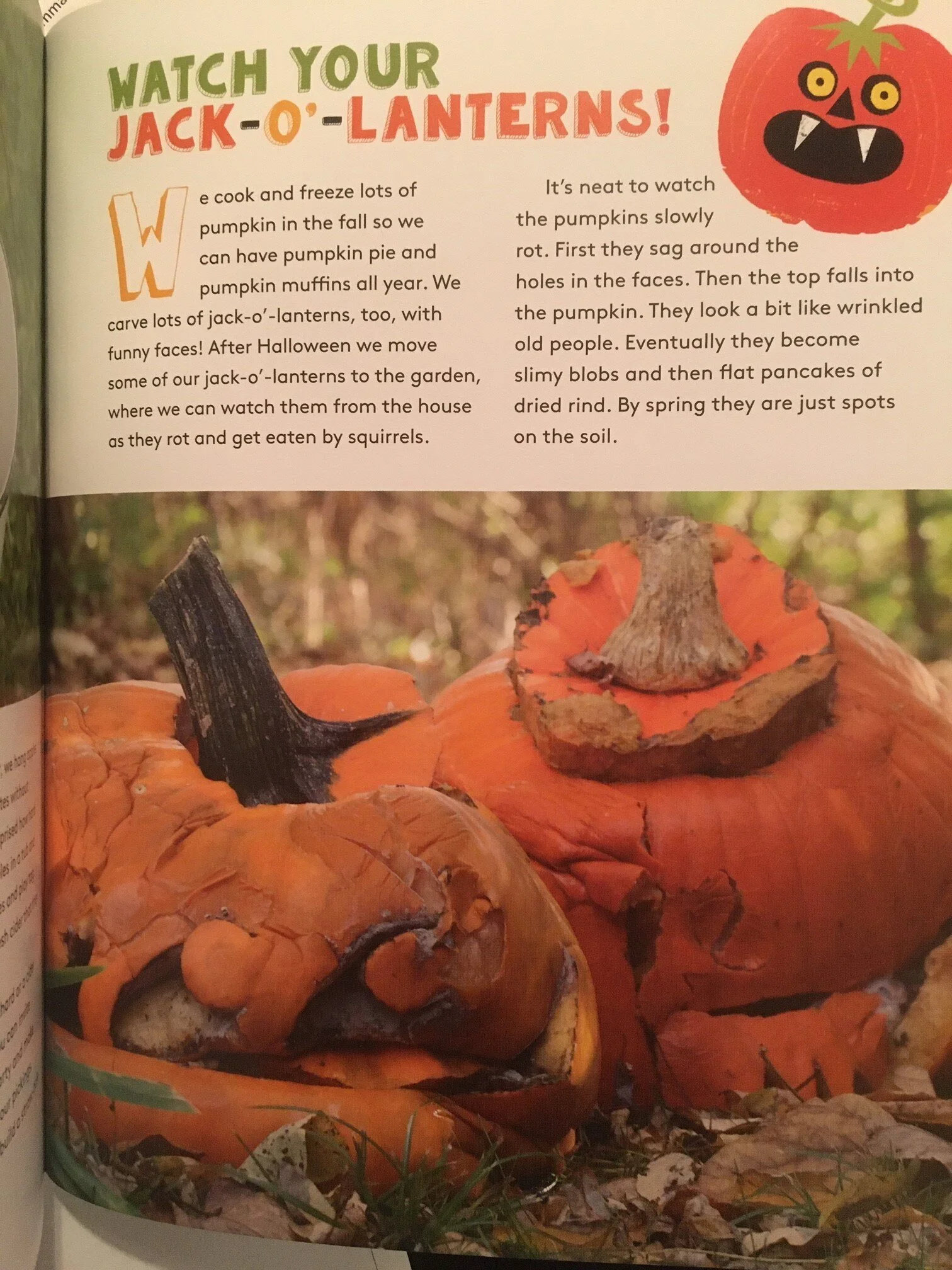

Watch Your Jack-O-Lanterns!

You must be wondering if we’ll eat all of those pumpkins on our front porch this year. We’ll use the pie pumpkins first, as they have a less watery, more flavourful flesh.

What doesn’t go into pumpkin pies, muffins, and soups feeds the soil.

My daugher Emma shares this idea in her book Gardening with Emma.

Sometimes we put our jack-o-lanterns in the compost pile. But what’s really fun is watching them slowly melt into the soil.

Each one ages differently!

In my daughter Emma’s book, Gardening with Emma, she tells kids how pumpkins in the garden start to sag, and then become spots on the soil by spring.

Written for kids by a kid, this guide helps kids see the fun side of gardening, whether it’s growing giant vegetables, making a bug vacuum, or making a sound-themed garden.

Emma shares lots of inspiring ideas for young gardeners about how to grow healthy food, raise cool plants, and have fun outdoors.

Copies from the Food Garden Life shop are signed by Emma!