Guide to Blanching in the Vegetable Garden

How to Blanch Celery, Cauliflower, and Other Vegetables. Blanching in the garden refers to covering up part of all of a plant to exclude light.

By Steven Biggs

How to Blanch Celery, Cauliflower, and Other Vegetables

One word, two meanings!

For many people, blanching vegetables means a quick dip in boiling water before freezing them. This type of blanching slows down or stops the enzymes that cause colour and flavour loss.

But there’s another type of blanching, and it’s something that we do right in the garden.

Blanching in the garden refers to covering up part of all of a plant to exclude light. Without light, it grows differently.

The result is a milder tasting and more tender crop.

Keep reading to find out what crops you can blanch—and how to do it.

Common Crops

These are crops that are commonly blanched in the garden. You can grow them without blanching, but blanching improves the quality.

Asparagus

Cardoon

Cauliflower

Celery

Endive and Escarole

Leek

Rhubarb

Different Ways to Blanch

Soil hilled up along a row of leek plants.

Depending on what you’re growing, and how you want to grow it, there are a few ways to blanch vegetables in the garden.

Remember, blanching just means excluding sunlight. Here are some ways to do it:

Cover the plant (e.g. inverted pots)

Hill the plant with soil

Wrap something around the plant (e.g. cardboard or newspaper)

How Long?

The plants are blanched for a few days to weeks before harvest – not the entire life of the plant.

Crop Blanching Tips

Asparagus

If you’ve ever seen white asparagus, these are spears that have been blanched by hilling with soil. It’s a delicacy in Europe, less common in North America.

Cardoon

Blanching cardoon plants by wrapping them in fabric.

I’ve heard of people growing cardoon in a trench…but it’s a pretty big plant needing a pretty big trench. Instead, wrap mature plants 2-3 weeks before harvest, leaving the top of the older leaves exposed, but the base covered. The idea is that the inner leaves are white and tender. Some people use cardboard, but I think the most elegant cardoon blanching I’ve seen was burlap coffee sacks.

Cauliflower

With cauliflower we blanch the head. White-headed cauliflower is blanched to keep it bright white. It is still edible if you don’t blanch it…but can develop a yellow or green tinge, and get a stronger flavour.

Blanching cauliflower by tying together leaves to cover the head.

As the developing heads begin to expand, tie leaves around them to keep out the light. Don’t wrap the leaves too tightly over the small head as it will need space to expand. I’ve heard of people using paper bags, but if there are leaves there, it’s easier and less wasteful.

There are also “self-blanching” types of cauliflower, with leaves that naturally grow around the developing head. Some of these varieties still benefit from additional wrapping.

Celery

With celery we blanch stalks for 2-3 weeks leading up to harvest, keeping the leaves at the top exposed. Blanching helps reduce bitterness and lighten the stalk colour.

Blanching celery with waxed milk cartons that have the top and bottom cut out.

As with cauliflower, there are also “self-blanching” celery types. These have a lighter colour and milder flavour.

Hilling soil around the stalks is one way to blanch celery. Grow celery in a trench, and then gradually fill in the trench with soil leading up to harvest. If you use soil, first wrap the stalks with newspaper, so you don’t get lots of soil between the stalks.

You can also blanch celery by tying paper around the stalks, covering with waxed cardboard milk cartons or tall narrow tins that have both ends removed, or surround the stalks with boards.

Blanching celery plants with boards.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Endive and Escarole

A board propped up over a row of endive or escarole is an easy way to blanch it.

Many people grow endive and escarole for the bitter taste. But you can blanch them to reduce the bitterness. Cover entire plants for a week before harvesting.

For individual plants, cover with a clay pot or a paper bag. For a whole row of plants, place a board over the row.

Leek

The base of leek plants can be blanched to give tender white flesh. In late summer, hill the base of the plant with soil, or wrap to exclude light. As with celery, leeks can also be grown in a trench that is gradually filled in as the plant gets taller.

Rhubarb

Blanch rhubarb by cover up plants with an inverted bushel basket as they begin to grow in spring.

When rhubarb is blanched it produces tender, elongated stalks that have a bright pink-red colour.

To blanch rhubarb, put an inverted bushel basket over the plant in the spring, as it begins to grow.

Why Not Blanche a Weed!

While a weed for many, dandelions are a kitchen staple for others. Our springtime menu includes dandelion frittata or a mixed salad with dandelion leaf pieces.

But dandelion, like its kin in the chicory clan, can be very bitter. The solution is to blanch dandelion. Simply cover with an inverted clay pot or a board – and you’ll be rewarded with tender, translucent, and mild-tasting leaves.

Blanching Challenges

Blanch dandelion by covering with an inverted pot or a board.

Blanching is easy to do. The biggest challenge is remembering to do it in time.

Another challenge is lightweight covers that blow away on windy days. If you use terracotta pots, they’re heavy enough to stay in place. But plastic coverings can blow away. The solution is to weigh them down with a brick or rock.

Top Blanching Tip

Put a note on your calendar to remind you to blanch your crops ahead of time.

Garden Blanching FAQ

Is Blanching Optional?

You don’t have to blanch these vegetables to eat them. But blanching gives a milder tasting, more tender, and more attractive vegetable.

What is “Self-Blanching?”

Some varieties don’t need help from gardeners with blanching. For example, with cauliflower, self-blanching varieties have leaves that grow to cover the head. Self-blanching celery has stalks with a mild flavour that don’t require blanching.

Why Grow Varieties that are not Self-Blanching?

You might be wondering why bother growing varieties that need blanching when self-blanching varieties are available. As you choose varieties, self-blanching is one trait to consider, along with other things such as having different harvest windows, price, and availability.

Looking for More Ideas?

Gardening Courses

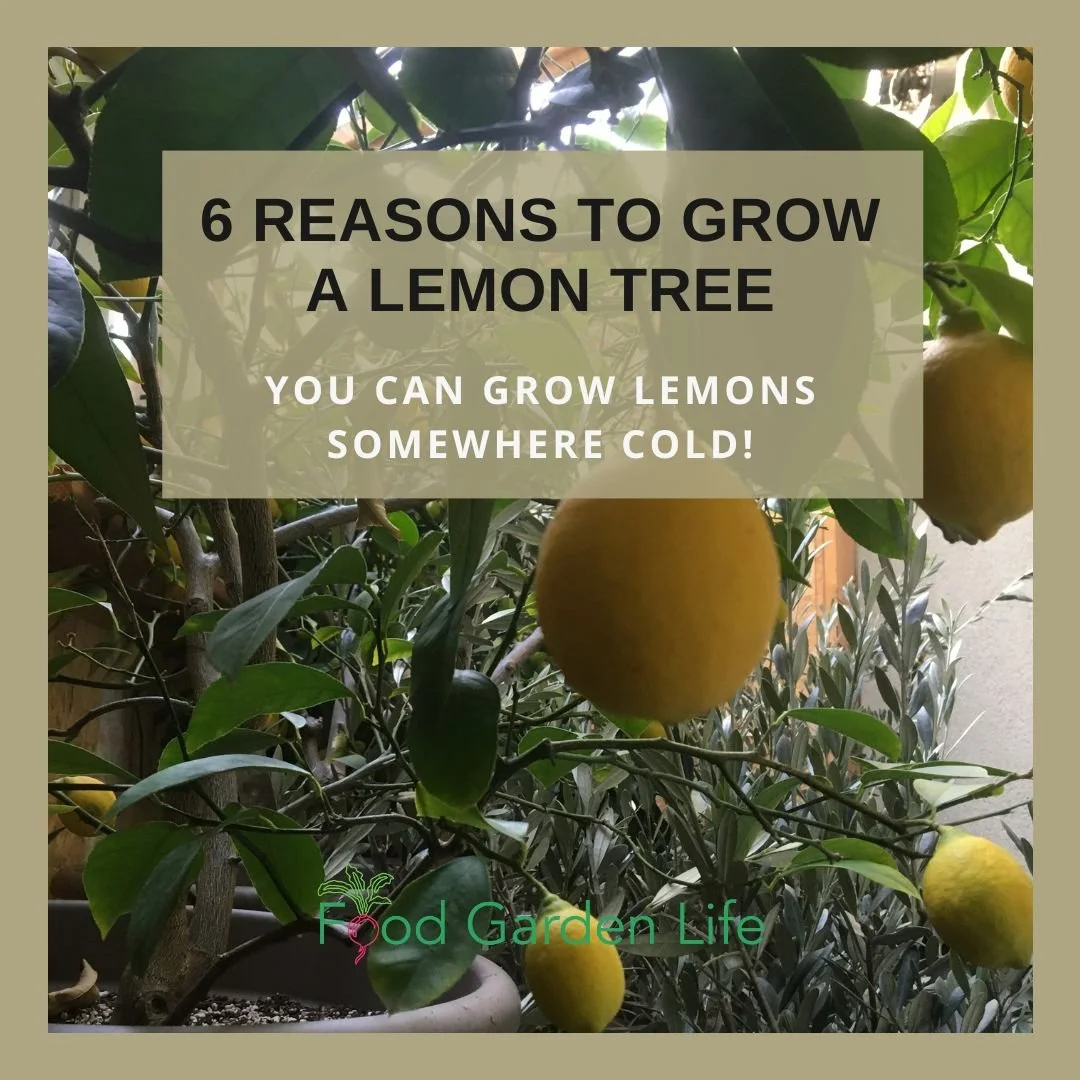

6 Reasons to Grow a Lemon Tree

You can easily harvest your own lemons if you grow a lemon tree in a cold climate. Here are 6 reasons to grow lemons in areas they don't normally survive.

By Steven Biggs

You CAN Grow Lemons Somewhere Cold!

Yes you can grow citrus trees. Even in places where they don’t normally survive the winter.

And I think that the best citrus for cold-climate gardeners to start with is a lemon tree.

There are many ways to successfully keep lemon trees alive over the winter.

You don’t need a greenhouse. And you don’t need a bright, sunny window.

Here are my Top 6 reasons to grow a lemon tree in a cold-climate garden.

1. Lemon Trees are Forgiving

As a student I worked at a small U.K. nursery that had the U.K. National Collection of citrus trees. I brought home a couple of small Meyer lemon trees in my suitcase at the end of that summer.

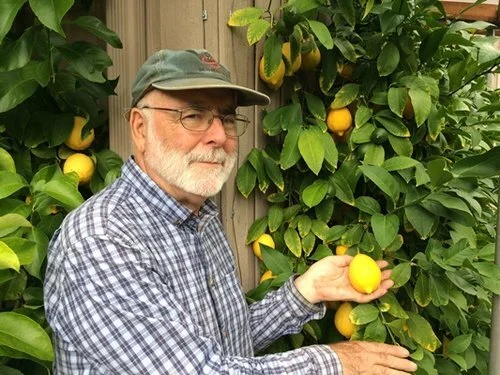

6 Reasons to Grow a Lemon Tree in a cold climate. A Toronto lemon harvest!

Then those lemon trees languished for years. I was a student and moved around a lot, so they went from fluorescent lights to dimly lit apartment windows. It wasn’t until I moved into my first house that I started to pay attention to my lemons.

When one of my now knee-high Meyer lemon trees bore over 50 lemons in one picking — the small tree was so laden with fruit it looked like it was doing yoga stretches — I was hooked!

But until then, that lemon bush withstood a decade of me not knowing what I was doing.

Find out How to a Grow Lemon Tree Indoors (That Actually Produces Lemons)

2. Lemon Trees are Cold-Hardy

When we moved from our bungalow to a house with an old sunroom that stayed just above freezing over the winter, my lemons were happier than they had ever been. The cool winter temperatures suited them. There were fewer insect pests, and when spring came, those trees flowered as they had never flowered before.

“One of my now knee-high Meyer lemon trees bore over 50 lemons in one picking!”

3. Lemon Fruits Ripen in Moderate Climates

While Bob grows lemon trees outdoors, he grows oranges and other “sweet” citrus in a greenhouse. Lemons don’t need this extra heat to ripen.

Lemons ripen in climates too cool to properly ripen other citrus.

Canadian citrus expert Bob Duncan lumps citrus into two broad groups: “sweet” citrus such as oranges and grapefruit, and “acid” citrus such as lemons and limes.

This distinction is very useful for cold-climate gardeners to understand because sweet citrus need a sustained high summer heat for sugars to develop in the fruit. Acid citrus, on the other hand, doesn’t need sustained heat to ripen.

Bob lives in the Pacific North-West region of North America, which has a moderate climate. To get his sweet citrus to ripen, he uses an unheated greenhouse. The greenhouse is for additional summer heat — not because of winter hardiness!

BUT THE LEMONS — an acid citrus — don’t need the greenhouse to ripen, even though the summer temperatures are not hot where he is. “With lemons, they don’t need as many summer heat units,” Bob explains. (“Heat units” is a concept often used in agriculture. It considers daily maximum and minimum temperatures and the heat that a plant experiences during a growing season.)

When you consider its combination of cold-hardiness and ripening requirements, lemon makes a very practical citrus for the home gardener in a cold climate.

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

4. There’s a Thrill in Pushing Boundaries

You may be surprised to learn that there is a history of lemons being grown way beyond the boundaries of where they could survive without human help.

The lemon has a bit of a cold-climate pedigree!

My daughter with a Ponderosa lemon tree and a lemon harvested in the spring. Note the smaller lemons that will ripen later in the year.

Time and again gardeners and farmers in areas that would normally be too cold for lemon cultivation have devised ways to grow lemons.

If you are interested in a delicious mix of history, horticulture, cooking ideas, and travel, check out The Land Where Lemons Grow: The Story of Italy and Its Citrus Fruit. Author Helena Attlee explores the history of citrus fruits in Italy, including some cool-climate adaptations. Of course, I didn’t read the book in the order it’s written. I went straight to the chapters about Amalfi and Lake Garda, which have a history of growing lemons in sub-optimal climates.

If growing a lemon tree in a cool climate sounds like a lot of bother, well, honestly … it is. But maybe you’re like me and enjoy the challenge of growing something that’s not supposed to succeed in your climate. You wouldn’t be the first.

5. Lemons are Versatile in the Kitchen

Some people are surprised to hear that I think it’s worth the effort of growing lemons even though they are widely available in supermarkets.

But trust me, it’s worth the effort.

Lemons are best when they are fresh. It’s no fun trying to zest or juice a shrivelled, dry lemon that has sat out too long. The easiest way to store lemons so that they stay fresh is on the tree—they last a long time on the tree!

In February I can pick a handful of Meyer lemons from the trees stowed in my greenhouse and make sorbet. The juice and rind of this lemon have a unique flavour (often described as a cross between a mandarin orange and a conventional lemon) that really can’t be beat.

There’s Also the Zest

I’ll also zest a Ponderosa lemon into our chicken kebab marinade. Again, a unique taste I can’t buy at the grocery store. The Ponderosa lemon zest is a bit lime-like to my taste buds. (It’s no surprise that it has a unique flavour because it is thought to have some citron, another citrus, in its ancestry.)

Don’t Forget the Leaves

When you grow your own lemon trees, you can harvest more than just the fruit: Mid-winter I will grab a few lemon leaves to wrap around kebabs that I’m cooking on the grill. Lemon leaves are fragrant when bruised or torn, and impart nice flavour into a kebab while keeping it moist.

Grow a lemon tree for the fragrant flowers that come out at the same time that fruit is ripening on the plant.

6. You Get Flowers and Fruit at the Same Time

Some citrus plants flower once a year. Bob Duncan’s oranges, for example, bloom once, in the spring.

Not Lemons! Lemons yield fruit at different stages of maturation and flowers all at same time.

Even after the main spring bloom is over, you can still enjoy the fragrance of the flowers. With lemons, home gardeners can enjoy harvesting fruit and the fragrance of blossoms year-round.

Good for the patio: good for the kitchen garden!

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

Lemon + Citrus FAQ

Do lemons grow on trees or bushes?

Both. How the plant grow depends on two things:

How you prune it.

Natural growth habit of the plant. (Meyer lemons have more of a bush-like growth habit.)

Are there indoor citrus trees?

The conditions in centrally-heated homes tend to be warmer and drier than is ideal for most citrus. You can still grow potted citrus in a bright window — but a cool bright sunroom or greenhouse is better.

For more about how to grow indoors, read this article about how to grow a lemon tree indoors.

How to you feed citrus trees?

Read this article about how to grow a lemon tree indoors.

Can you grow oranges in Canada?

You can grow oranges in a greenhouse, or as a potted plant that gets winter protection.

Want More Lemon-Growing Articles?

Simple Home Preserving

Simple ways you can preserve your garden harvest without canning.

By Steven Biggs

Simple Preserving Techniques

Preserving often brings to mind piping hot mason jars, bags of sugar, the stinging aroma of boiled vinegar, and a hot, steamy kitchen—all hallmarks of canning.

But there are many other preserving strategies that are simpler and less energy-intensive.

Sauerkraut is a great example of a simple method of preserving. All it takes is cabbage, salt, and time.

Preventing Spoilage

We preserve food by preventing the growth of spoilage organisms:

These organisms include fungi (e.g. moulds) and bacteria (e.g. botulism), and insects

We prevent their growth with conditions that don’t suit them: acidic, cold, lacking in oxygen, or dry

Sauerkraut

Enjoy your garden harvest year-round by using a few simple preserving methods. Simple is the key word: the simpler it is, the more likely it is to get done.

I was pretty excited the first time I made sauerkraut. No more insipid, store-bought kraut: I wanted the good stuff. With fennel seeds, juniper berries. Maybe even some apple slices. My great aunt Anna later taught me to put a whole head of cabbage near the bottom of the crock, so I could have whole sour cabbage leaves for making cabbage rolls.

You can’t get more tactile in food prep than making sauerkraut. It takes repeated punches to the salted, shredded cabbage until a film of liquid starts to show. The arm motion I find works best is a bit of a punch with a twist.

Once the cabbage is softened and there’s liquid, I added a bit of brine so I have enough liquid to pin down all the shredded cabbage under a weighted plate and have it submerged.

Then it’s time to let it ferment.

The first time I made it I kept the crock in the house. It didn’t win me any favours with my wife, Shelley.

It stank. I remember her saying to a technician at the door, I’m sorry about the smell, it’s my husband, he’s making sauerkraut.”

Now I make sauerkraut in the garage.

Bugs Too

A stint in the oven at low heat, or storing dry beans in the refrigerator is a simple way to deal with bean weevils.

Insects are spoilage organisms too. One year I found lots of scampering weevils drilling holes into my dried beans.

After making sure our stored food is insect-free, the next thing to do is have food in a sealed container — where insects can’t get to it.

Make sure that there are no hidden travellers or eggs: Even though my dried beans were in a closed jar, they included weevil eggs. If I had used a heat treatment to kill the eggs, I wouldn’t have had a jar full of weevils.

Fermentation

Lactic-acid-fermented dilly garlic cucamelons.

Lactic-acid fermentation is what makes sauerkraut sour. It’s a naturally occurring process during which lactic-acid forming bacteria multiply rapidly, giving off enough lactic acid to preserve the cabbage.

Despite the sour flavour, sauerkraut is made without vinegar.

This same fermentation process can be used for other vegetables too. Brined (fermented) dill pickles taste different from pickles made with vinegar—it’s the lactic acid that makes these pickles tangy.

Like sauerkraut, brined cucumbers undergo a fermentation process that produces acidity. This acidity then prevents the growth of spoilage organisms. Other vegetables such as cucamelons, beets, carrots, beans, and onions can also be fermented.

Other Preserving Techniques

Drying herbs. TIP: If drying herbs in the sunlight, cover them with a paper bag to get dry herbs that aren’t bleached by the sun.

DRYING is a simple preserving technique that works because most spoilage organisms need moisture to grow. While the drying of fleshier produce with a high moisture content might be best done in the oven or a food dryer, other crops dry very easily.

Herbs are one of the easiest things to dry. They hang in bundles from my garage ceiling, while linden flowers and elderberries are spread out on metal pie plates or cookie sheets. The dry bean plants hang by the roots to dry until the fall, when the beans are removed from the shell and stored in jars.

A dedicated drying room or shed isn’t necessary. Try drying herbs in the kitchen window. We’ve had good luck with strings of hot peppers or the wild mushrooms that we dry in the kitchen—we’ve even used the hot dashboard of a car to dry plates of elderberries.

FREEZING doesn’t kill all spoilage organisms, but it puts growth on hold.

My favourite freezing method is a simple technique for herbs. I love dill—and lots of it. In late spring there’s so much in the garden that I have to weed it out from the other crops. Instead of drying it in the sunny shed, where the sunlight causes it to fade to grey, I simply chop it then freeze it in a plastic tub or jar. I have ready-chopped dill all season long. The same technique works well for parsley too.

The Easiest Preserving Technique

What’s the easiest preserving technique? Leave the crop in the garden as long as possible.

Parsley can be retrieved from under the snow

In winter, the few leeks that remain in the garden make a nice stew during a mid-winter melt

Carrots and parsnips can be kept in the garden well after the first frost—in fact, they sweeten up with the cold weather as starches are converted to sugars

Ripe lemons can remain on the tree for months

Here are 25 storage crops you can grow in your garden to store for the winter.

I’ve had fun over the years getting my kids to help punch down the shredded cabbage to make sauerkraut!

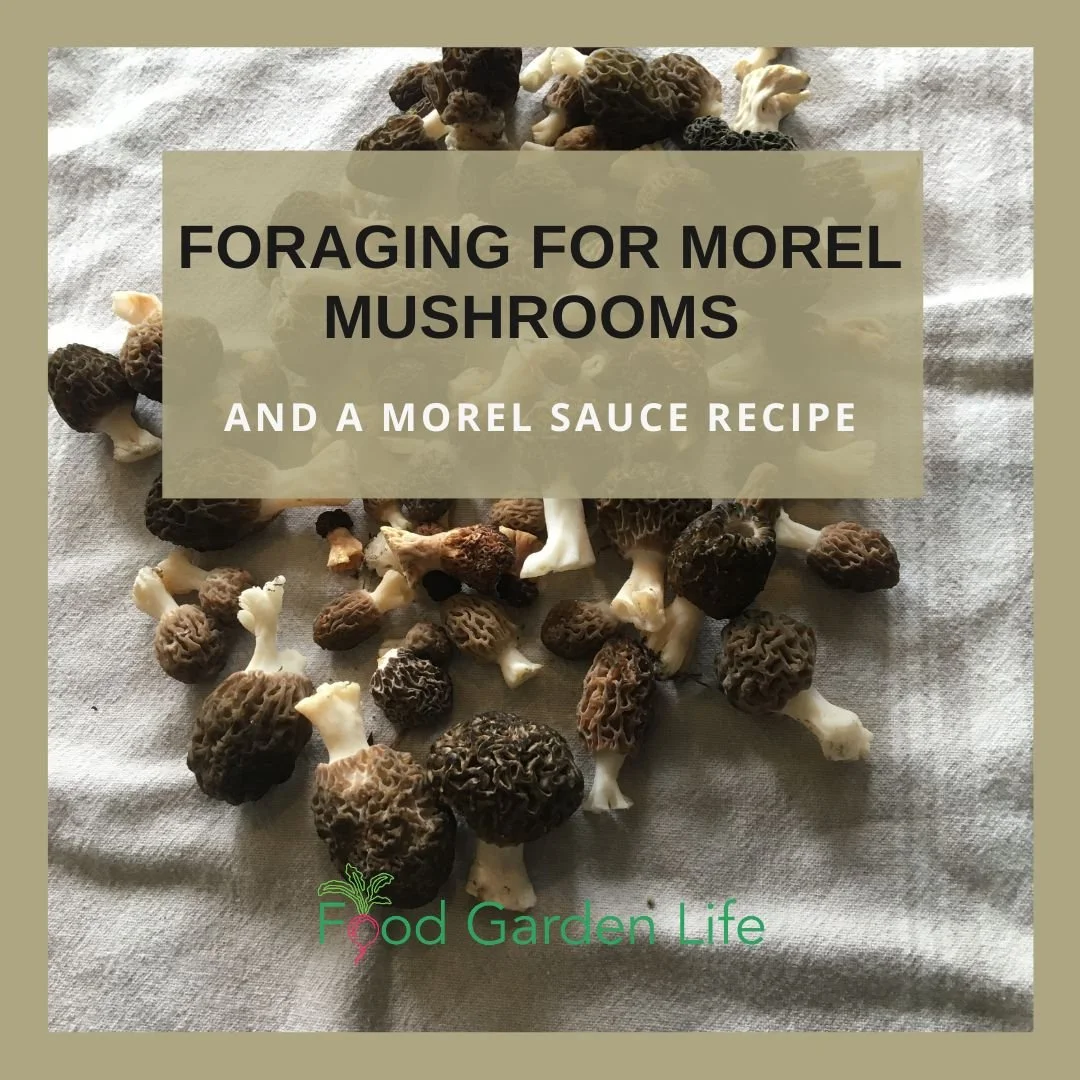

Foraging for Morel Mushrooms (and a Morel Sauce Recipe)

Here is the recipe for my morel sauce.

By Steven Biggs

How to Find Morel Mushrooms

I recently posted a picture of morels on social media and mentioned I make them into a sauce. I had a few requests for the recipe, so here it is. I hope your family enjoys it as much as mine!

I love a springtime walk through the woods to look for morel mushrooms. I love cooking with morel mushrooms.

But there’s something else I love too: the hunt.

Walking slowly, scanning the ground: It takes intense focus. And I find that time spend in the woods, focusing on what I’m seeing, is a beautiful time for me.

When I spot a morel, I stop in my tracks and then scan the ground all around it — because where there is one there are often more. And I don’t want to step on any of them!

When the lilacs bloom, I figure it’s time to look for morels. Some years I get lots; some years not as many. Either way, it’s a spring ritual I love.

Keep reading to find out more about foraging for morel mushrooms—and for my recipe for a delicious morel sauce.

Morel mushrooms can be difficult to spot. But once you see one, look all around, as there will often be more in the area.

A Great Family Activity

My wife, Shelley, and I started mushroom hunting before we had kids. And once we had kids, we kept on mushrooming.

I’d carry babies on my back…though it’s harder to bend over to pick the mushrooms! Or we’d choose locations where we could pull along a wagon.

For small children, a basket makes morel hunting fun. Maybe they’ll find morels — maybe leaves or pine cones or snail shells.

One thing is for certain: Kids are lower to the ground, and they can be very observant. We’ve had many trips to the woods where the kids spot mushrooms before we do.

My daughter Emma on a springtime morel hunt with us when she was little.

Kids are lower to the ground, and they can be very observant. We’ve had many trips to the woods where the kids spot mushrooms before we do.

Morel Sauce Recipe

This sauce is great for lubricating crepes filled with ham and steamed asparagus (make sure to put some sauce inside the crepe before you wrap it up, and then put more sauce over the top of the crepe once it’s all wrapped up!)

It’s nice on grilled poultry. Or, use it spooned over a fried egg. (And…you might just want to taste a couple of spoonfuls of sauce on its own, just don’t let anyone see you do it!)

Crepes with morel sauce, inside and out. Don’t be stingy with the sauce!

This recipe uses the trinity of mushrooms, cream, and white wine. It’s not adulterated with lots of herbs, so the mushroom flavour shines through.

Depending on the time of year, you can use dry or fresh morels. (Of course, you can use other mushrooms too…but the morels are my favourite.)

Ingredients:

10 morels, coarsely chopped

1 shallot, minced*

½ cup white wine

3 cups stock (chicken or veg both work well)

1 cup heavy cream (don’t wimp out with light cream – you want good, heavy cream…this isn’t supposed to be a low-fat sauce)

1 tbsp butter

Salt and pepper to taste

*Don’t worry if you don’t have a shallot…use a cooking onion instead and it will be fine.

If using dried morels:

Start by reconstituting them in ½ cup of water for about 30 minutes before chopping

Reserve the liquid (strain if needed)

Instructions

Cook shallots in butter until translucent

Add morels, salt, and pepper and cook another 2-3 minutes

Add wine and stock (and reserved liquid, if using dry morels) – and cook until reduced by about 2/3

Add cream and simmer about 20 minutes, until the sauce will coat the back of a spoon

I love morels. And I love the hunt for morels!

A Final Note on Morels and Mushroom Hunting

Don’t eat what you can’t identify.

Full stop.

Neither Shelley or I grew up with morels. We didn’t know where to look for them or how to identify them. But experienced friends took us out mushroom hunting.

Then we joined a local mycological society (the fancy term for a mushroom club) which had forays to nearby woods. The forays were a great way to be around people who were knowledgeable about mushrooms and could help us identify what to eat — and what not to eat.

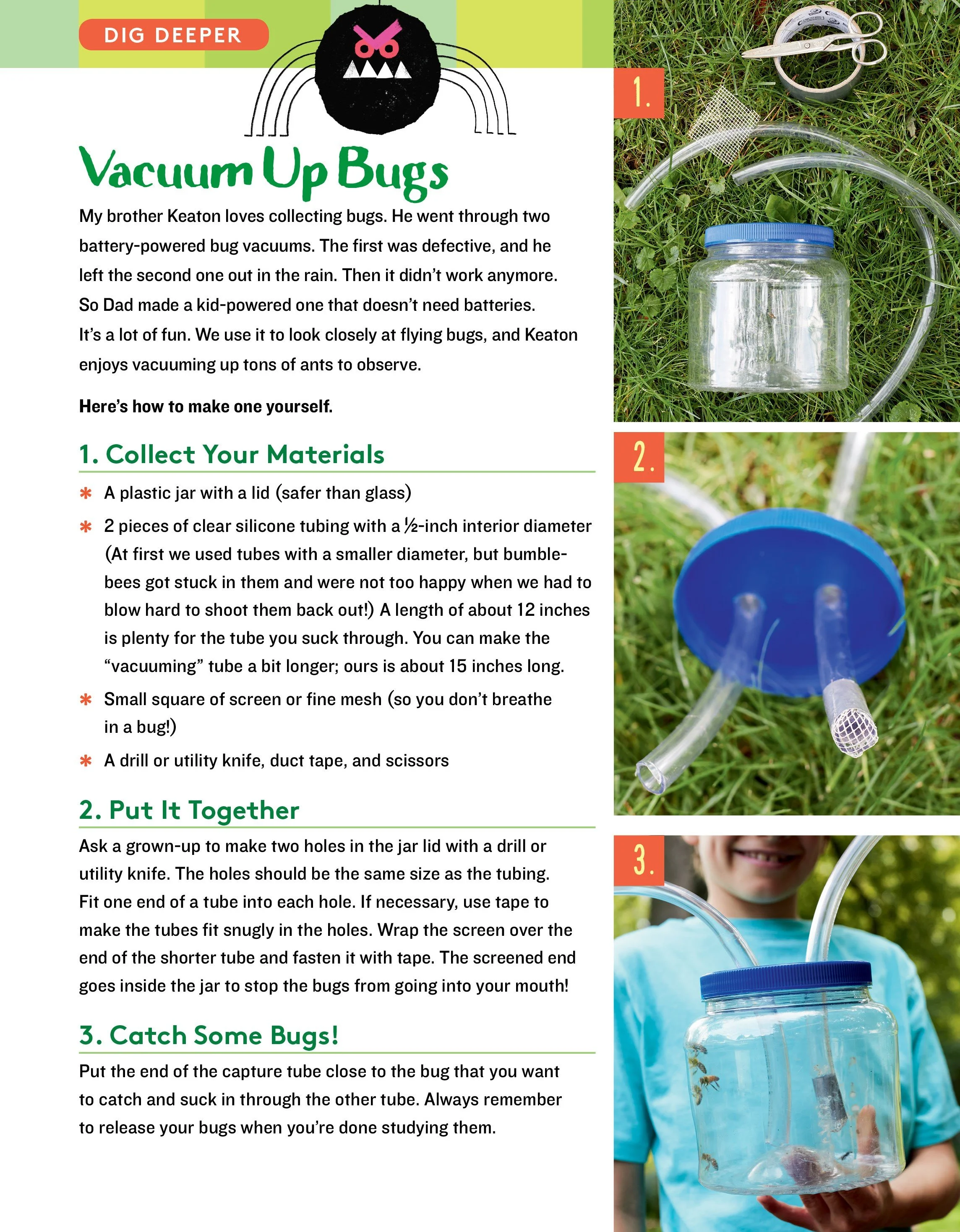

Make a Bug Vacuum

Make a bug vacuum.

By Steven Biggs

A Bug Vacuum is Fun for Kids

Not sure how to make the garden a fun place for kids?

It doesn’t always have to be about plants. Some kids might want to climb trees. Some might enjoy mud.

And some kids LOVE bugs.

My son Keaton has always gravitated towards bugs. When he was smaller he’s spend big chunks of time scouring our yard for bugs to suck up and inspect in his bug vacuum.

Make a Bug Vacuum with your Kids

You can purchase bug vacuums. But those battery-powered gadgets soon break.

Instead, make this bug vacuum with some easy-to-find materials.

Even better, make it with your kids. It’s a fun and easy project to tackle together.

Here’s a simple bug vacuum that you can make at home (from the book Gardening with Emma.)

My son Keaton catches a pollinator with his bug vacuum. After watching it, he unscrews the lid to release it. Photo Donna Dawson.

Looking for more fun ideas to make the garden a fun place for kids?

Check out Gardening with Emma for lots of fun ideas and projects for kids (and parents!) in the garden.

Written for kids by a kid, this guide helps kids see the fun side of gardening, whether it’s growing giant vegetables, making a bug vacuum, or making a sound-themed garden.

Emma shares lots of inspiring ideas for young gardeners about how to grow healthy food, raise cool plants, and have fun outdoors.

Copies from the Food Garden Life shop are signed by Emma!

Grow Vegetables in Straw Bales

Straw bale vegetable gardening is an easy way to create more growing space.

By Steven Biggs

Make More Growing Space with Straw Bale Gardens

I started straw bale gardening to solve a problem.

The problem? We needed more growing space for my daughter Emma’s 100-plus tomato varieties.

We have a big yard for the city. But there’s a black walnut tree that makes much of the yard unsuited to growing tomatoes.

(That’s because black walnuts give off a compound that kills the tomato plants…and a number of other plants too.)

With a long and ugly driveway that could fit a couple of school buses, Emma and I began to imagine a tomato plantation on the driveway.

In this post I’ll talk about how to use straw bales to make gardens on paved areas or over soil that’s not great for gardening.

Straw Bale Driveway Garden

Straw bales are an easy way to create a near-instant garden on paved surfaces and areas with poor soil. That’s because the straw bale is both the growing medium and the container.

Here’s how it works: As the straw bale decomposes, it creates an ideal growing medium that is well aerated and holds lots of moisture. It’s like a big sponge. It’s perfect for plant roots – better than many garden and container soils.

In short, you’re composting a bale of straw, and growing your vegetable plants in it at the same time.

Straw Bale Gardening: Top Tip

Our straw bale driveway garden

The most important thing to remember is that bales should be “conditioned” before you grow in them.

Conditioning means kick starting the microbial action. And you know when it’s working because as the microbes start to break down the straw, the temperature inside the bale goes up. We don’t plant in it yet…it might be too warm for our plants.

As the temperature comes down, your bale is ready to plant. Some people use a thermometer. I stick in my finger. It’s not an exact thing.

I allow 3-4 weeks for this conditioning process. It might be less if you’re somewhere warmer than me.

Since the bales in our driveway garden are for heat-loving tomato plants that we put out in late May, we start conditioning the bales late-April to make sure they’re ready for the planting date. I just work back four weeks from my planting date.

Straw Bale Garden Setup

Emma conditioning the newly arrived straw bales.

Before your bales become heavy from watering them, it’s a good time to think about how you want to arrange them. There’s no right or wrong, it depends on your situation:

If you’re planning to use a long soaker hose, you might want them in a long line.

If you’re gardening with kids, arranging them in a square makes for a nice hidoute once the plants get bigger

If you’re watering with a hose, arrange the bales so you can easily move amongst the bales with the hose

How to Orient Straw Bales

Once you know how you want to arrange the bales, think about how you’re orienting them. You can place them so that the loops of twine are on the top and bottom – or the twine is at the sides. Both ways of orienting the bales are fine.

But here’s how I do it: When positioned so that the twine is at the sides, the straw within is mainly oriented vertically. Bales positioned this way absorb more water, so it’s less likely to run off of the side of the bale.

How to Condition Straw Bales

To condition the bales – which just means getting the microbes working – we need 2 things:

Water

Nitrogen

In this picture the bales are oriented with the twine at the top and bottom of the bales. We now prefer to have the twine at the side for easier water penetration.

Place a nitrogen source on top of the bales and water well. The goal is for the water to soak into the bale and move some of the nitrogen into the bale. Use a low pressure and volume so that water doesn’t flow over the sides of the bale (and take the nitrogen with it).

More on the nitrogen source: When you’re looking at the numbers in the fertilizer formulation, you want the first number, the nitrogen, to be higher than the others. For example, blood meal is 12-0-0. That’s what I usually use.

Other years I’ve also used a high-nitrogen organic fertilizer derived from guano, and a lawn fertilizer.

Here’s how I condition straw bales with blood meal:

I water well every day for the first week.

Starting on the first day, and again every other day, I put a 2 cups of blood meal on the bale BEFORE watering (so the water moves some of the blood meal into the bale).

I give 3 applications of blood meal.

As we get into week 2, the bale should be warming up nicely inside!

After 2 weeks, fertilize the bales with a balanced, all-purpose fertilizer.

During this conditioning process, the temperature can go up to about 50°C (120°F), and then it drops. You can plant in the straw bales once the temperature has dropped below about 26°C (80°F)

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Straw-bale Garden Plant Layout

Plant densely to make the best use of space in your straw bale garden.

Wondering about plant spacing in a straw-bale garden? Because a well-managed straw bale garden provides plants lots of moisture and an excellent growing medium, you can plant densely.

We aim for two or three tomato plants per bale. Around those tomatoes we sow bush beans and leafy greens.

Something else to think about with straw bales is that you can plant into the side of the bale too. We’ve grown dwarf tomato plants out the side of bales, while at the top are normal determinate and indeterminate varieties.

How to Support Plants in Straw Bale Gardens

Because there is a paved surface below, and because the bales decompose and start to collapse over the summer, regular staking is not an option.

Here’s what I do instead of staking:

Use 3-4 stakes positioned over the bale to create a self-supporting tee-pee.

Put the bales next to a fence and grow vining crops up the fence.

Looking for tomato-staking ideas? Find out how to stake and support tomato plants.

Straw Bale Garden Planting and Care

How to Plant in Straw Bales

When I show pictures of straw bale gardens to groups, I’m asked where the soil is. There doesn’t have to be soil, because the straw is the growing medium.

When transplanting, use a trowel to pry an opening into the bale. Then place the transplant into the opening, and close up the opening. Be sure to cover the transplant roots with straw so they remain moist.

With large seeds like beans, we just insert them right into the bale. Again, no soil necessary.

When direct seeding smaller seeds onto a straw bale, a thin layer of soil is helpful. We add about an inch of soil over the top of the bale if we’re seeding leafy greens. Use a potting soil or good garden soil that won’t cake with frequent watering.

Straw Bale Garden Fertilizer and Water

Once your bales are conditioned and planted, feed with a balanced, all-purpose feed and keep them well watered. Because the inside of the bale remains well aerated, excess water is not likely to harm the plants. But excess water will wash away nutrients.

If there are not many bales in your garden, hand watering might be fine.

For larger gardens, drip irrigation or a soaker hose works well. Position the soaker hose to sprays downwards, into the bale.

Grasses and Mushrooms on Straw Bales

It’s normal to get mushrooms growing on straw bales. It means you’ve created good growing condtions.

Don’t be surprised to see little grass-like plants and mushrooms growing on the bales. These are good – it means you’ve created good growing conditions.

The grasses are any residual grain within the bale that germinates and grows. They won’t out-compete your crops. Just pull them off.

Straw Bale FAQ

What do you do with Straw Bales After Harvest?

After a year of growing I use the straw to mulch gardens, on pathways, and in my compost pile.

How Many Years do Straw Bales Last?

I’ve sometimes used bales a second year. How fast a bale decomposes varies with your weather conditions. Friends in warmer areas report that one year is the maximum for them.

What if the Twine Breaks?

Broken bales? No problem. In this straw bale garden the tall sections are tomato cages filled with loose straw from broken bales.

If possible, tie it back together; or use a new, longer piece of twine to tie together the bale. If that doesn’t work, you can pack straw into a cage or pot instead.

As you carry the straw bales, try to do it in such a way that the twine does not slide off the side of the bale.

Do Straw Bales Leave Marks?

Yes. Straw bales can darken paved surfaces.

I don’t recommend using them on wood because it creates conditions that could speed up the decay of the wood.

One year I had them against a board fence, and it resulted in dark marks on the fence – so I now position the bales a couple of inches away from the fence.

What About Hay Bales?

Hay bales can also make an excellent growing medium, but there are a couple of reasons they’re not used as frequently as straw bales:

Hay often includes lots of grass seed – not something you want to introduce to your garden

Hay is often more expensive than straw

What are the Best Plants for the Straw-Bale Gardening method?

You can grow a wide range of vegetable crops in straw bales.

Heat-loving crops benefit from the warm root zone in the bales

Root crops develop very well in the well-aerated growing medium

Leafy greens grow well and can be planted underneath other crops such as tomatoes

Cascading plants such as nasturtiums (for edible flowers!) can drape down over the side of the bales

Where can I Buy Straw Bales?

Straw bales are fun for kids.

I used to bring home loads of bales in my minivan. And my family hated all the prickly little bits of straw it left everywhere. So now I just get straw delivered.

To find a farmer, use an online classified advertising website.

And if you have kids: Get straw bales earlier than you need them – for your kids. Straw bales are like giant, biodegradable Lego blocks.

Don’t Straw Bales attract Rats?

The mention of straw has some people wondering whether straw bale gardens will be overrun with rats.

It’s a good question. Not in my experience.

The thing to remember with rats and mice is that they’re looking for food, shelter, and water.

A bale on a paved surface doesn’t give them burrowing room. Doesn’t give them water. Doesn’t give them much food.

What’s more likely to attract rats is bird baths, bird feeders, leaving out pet food, and improperly stored garbage. (On that note, gardening itself, and growing plants with seeds and fruit that are food for rodents, attracts rats.) Remember too, that they’re already abundant in many areas – just not out and about at times that we see them.

More Vegetable Garden Techniques

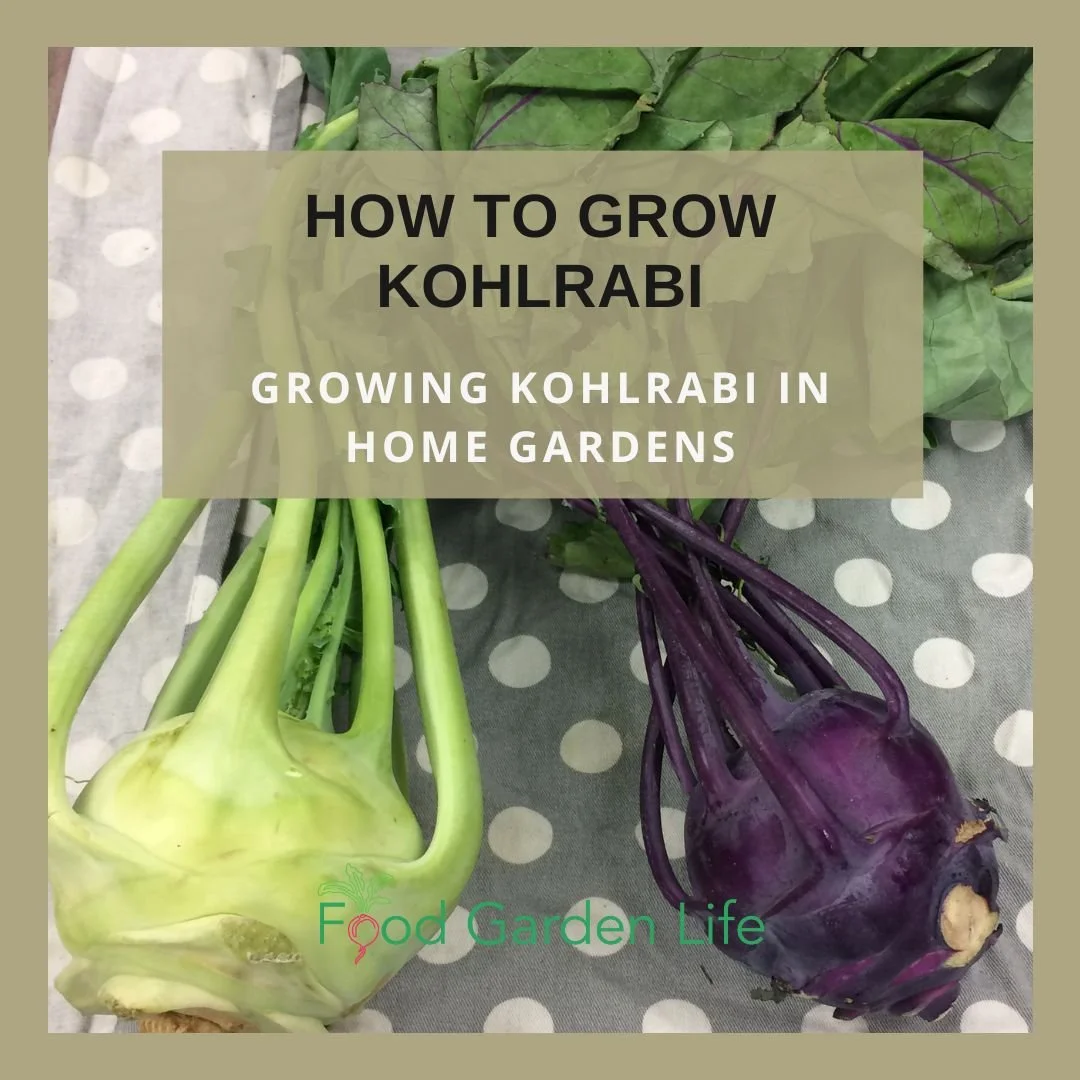

How to Grow Kohlrabi

How to grow kohlrabi.

By Steven Biggs

Growing Kohlrabi in Home Gardens

THREE CHEERS for one of the most photogenic veggies out there.

To my kids, kohlrabi looked like flying saucers. When I look at kohlrabi from the right angle I see a person having a bad hair day.

Whatever your imagination paints it as, it’s both attractive and unusual, making it a nice fit for an ornamental edible garden.

It’s also easy to grow, quick to mature, and versatile in the kitchen.

If you haven’t tasted it before, I’d describe the flavour as a cross between a mild apple and mild turnip. Let’s call it turnip light!

In this post I’ll talk about how to grow kohlrabi and how to fit it into your garden.

It Starts as a Rosette

Kohlrabi is a member of the cabbage clan. It has an edible stem that fattens up right above the soil level. Before the stem plumps up, though, the plant is a rosette of leaves. As the stem thickens, the symmetry of that rosette remains, with leaves projecting out from the bulb-like stem.

Top Tip for Kohlrabi Success

Here’s the key to your kohlrabi success: Fast, uninterrupted growth.

To get that type of growth, grow the plant in well-fed soil, with cool temperatures and consistent moisture.

Site

Kohlrabi is an easy-to-grow vegetable that is versatile in the kitchen.

Like its cabbage cousins, kohlrabi grows best in soil with lots of organic matter

A spot with full sun is best (although I’ve had decent results growing kohlrabi in partial shade)

Grow Kohlrabi from Seed

Kohlrabi is easy to grow from seed, indoors or outdoors. I don’t usually bother starting them indoors in the spring, but it’s an option if you want the earliest possible harvest. If you start them indoors, there’s no need for a heat mat.

Sow seeds approximately 5 mm (1/4”) deep

Outdoors: Start sowing about 1 month before the last spring frost

Indoors: Start kohlrabi transplants about 1 month before you plant to move them to the garden

Here are a couple of ways to get a longer kohlrabi harvest:

Start additional seeds every 2-3 weeks

Grow more than one variety, choosing varieties that take different amounts of time to mature

A young kohlrabi plant, before the stem has started to fatten up.

Note: While kohlrabi plants are tolerant of cold weather, a hard freeze can cause young plants to bolt – to jump right to the flowering stage. That would mean no thick edible stem. So there’s a limit to how early you can plant them out.

Kohlrabi as a Summer Succession Crop

When kohlrabi is a succession crop, I like to pre-start seedlings indoors (or outdoors, in another part of the garden). That way, I have transplants ready to go once the desired space opens up.

While I rarely start spring kohlrabi indoors in the spring, I find it’s the best way for me to grow kohlrabi for summer succession because:

It allows me to have a tighter succession...with larger plants ready as soon as the space is open

The hot, dry summer weather that I get here is not ideal for outdoor seeding

Note: Depending on growing conditions in your area – and how much attention you give your garden over the summer – kohlrabi might or might not be a suitable summer succession crop. Dry conditions can cause erratic growth and give a woody texture with a strong, bitter flavour.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Spacing

Thin kohlrabi plants to give a spacing of approximately 10-15 cm (4-6”) apart.

With direct-seeded kohlrabi, I usually plant them more densely than recommended. Then I thin out the row as the stems begin to fatten, enjoying an early harvest of young kohlrabi.

Kohlrabi leaves are edible, so if I thin out any plants before the stems enlarge, I can still add the leaves to a salad!

Planting more densely is also cheap insurance against losses and poor germination.

If you’re aiming to grow larger kohlrabi, increase the spacing a bit – and look for a variety know for size.

Sow the seeds approximately 5 cm (2“) apart

Thin to 10 – 15 cm (4-6”) apart

Space rows 30cm (12”) apart

If you’re aiming to grow larger kohlrabi, increase the spacing a bit – and look for a variety know for size.

Challenges

I find the early crop is not bothered much by pests. But later sowings and summer-succession transplants are growing when there are more pest pressures in the garden. That means young seedlings can be vulnerable to flea beetles, cabbage worm, and cabbage looper. An easy solution is to cover young plants with a floating row cover.

Where possible, rotate crops to minimize pest and disease pressures. That means it’s best not to plant kohlrabi where you’ve had you’ve had related crops (broccoli, cauliflower, collards, kale, turnip, rutabaga, cabbage, bok choy, Brussels sprouts, and mustards) in last 4 years.

Harvest and Storage

Kohlrabi usually take a couple of months to mature. Pick when they’re anywhere between the size of a golf ball and a tennis balls. Remember: smaller will be more tender.

Kohlrabi is frost hardy, so there is no rush to harvest it in the fall.

In the Kitchen

Kohlrabi is versatile in the kitchen.

You can eat kohlrabi raw or cooked. Either way, peel it first, because the skin can be tough. I prefer to use a paring knife (sometimes a potato peeler gets stuck on the spots where the leaf joined the stem.)

Here are some ways I’ve enjoyed serving kohlrabi:

Sliced, on a veggie platter

Grated, in slaws and salads

Poached (in white wine with butter is nice!)

Cut into ribbons, and added to a stir fry

Cubed and added to curries

Remember: The young leaves and leaf stalks are edible too!

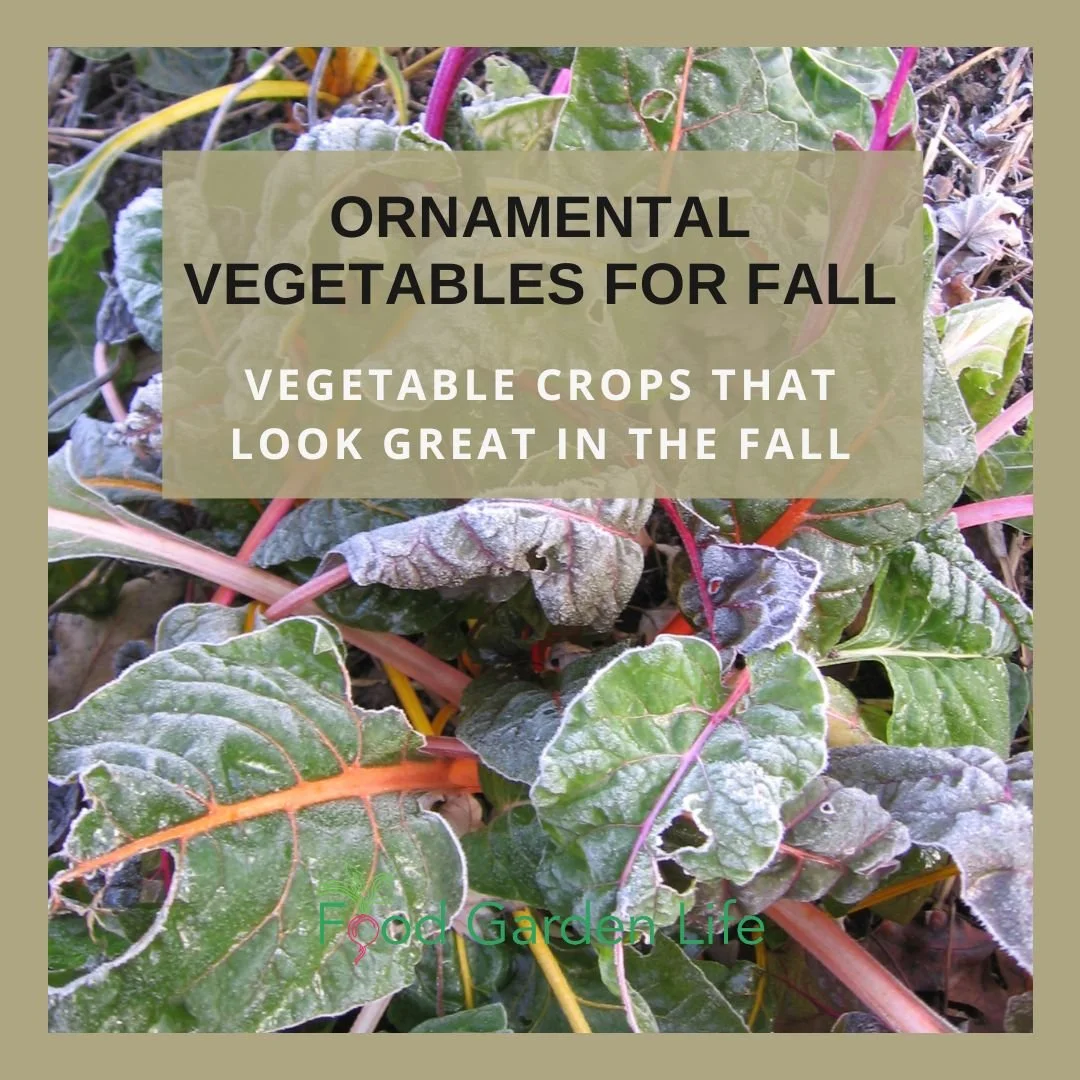

Ornamental Vegetables for Fall

By Steven Biggs

Vegetable Crops That Look Great in the Fall

As I write this, it’s spring. But I’m picturing my fall garden.

I was just scouting out the spot where my Swiss chard will go this year.

I always fit in chard close to my kitchen window.

An Ornamental Edible

In the garden outside my kitchen window I weave together the ornamental and the edible. I especially treasure edible plants with ornamental appeal.

And that’s where chard fits in.

Swiss chard paints this part of my garden in yellows, reds, pink, and orange.

Summer-Long Production

Leafy greens like lettuce, spinach, and arugula come and go with summer heat.

They bolt

They get leathery

They get bitter

But Swiss chard sails through the heat with a prodigious output of tender leaves.

A Long-Lasting Edible

As cool, grey fall weather arrives, Swiss chard is a bright spot in a fading garden.

It shines.

When frost renders swathes of the garden a wilted green-brown, chard still shines. The bright leaves bow to the frost, then spring back up as sunshine warms them.

It perseveres until a hard freeze.

Put Chard Where You Can See it in the Fall

I’m picturing the spot where my chard will go, and making sure it’s somewhere I can enjoy looking at it from my kitchen window through the fall.

More Ornamental Vegetables for the Fall Garden

Cardoon is another ornamental vegetable that looks great in the fall. Find out more about cardoon.

Artichokes hold up nicely in fall weather. Find out how to grow artichoke.

Home Garden Soil Contamination

By Steven Biggs

Understanding the Risk of Soil Contamination Around Your Home

AFTER MOVING INTO MY WORLD WAR I-ERA HOUSE, I decided to find out if the paint-chip-studded soil next to the house was safe for growing edible crops.

Many pre-1991 paints contained lead, and those that are pre-1960s—particularly exterior paints—are thought to be the worst culprits.

Lead was also used as a gasoline additive into the 1990s. So urban areas with older buildings, where there have been years of car exhaust—and maybe even industrial emissions—tend to have higher soil lead levels than rural, agricultural areas.

With this in mind, I wanted to understand what, if any, risk lay hidden in my soil.

If you’ve wondered what, if anything, to check with the soil in your garden, keep reading for a practical way to approach soil contamination.

Conflicting Information

With an older house, I was worried about lead contamination from paint.

The more I delved into the question of urban soil contamination, the less clear the issue became.

I found a government fact sheet saying there was minimal risk to consuming veggies grown in soil with lead levels below 200 parts per million (ppm)

But one from another jurisdiction advising 300 ppm.

Both noted increased risk for children (think soil moving hand to mouth), in which case one gave a safe upper limit of 100 ppm.

I was left wondering whether I should go with 100, 200 or 300 ppm.

So I Got on the Phone

When I called Ontario’s Ministry of the Environment, I was told that contaminant levels in typical agricultural soil are often less than urban areas, but there should be no concern as long as the readings for my soil fell below the residential standards, as set out in the provincial Environmental Protection Act.

But…I should also keep in mind that a reading above that residential level isn’t necessarily unsafe.

Understanding soil contamination was starting to seem as fun as doing my tax return.

So, after scanning the Act, I added 45 ppm lead (for typical agricultural soil), 120 ppm lead (for residential standards), and a big question mark (for “isn’t necessarily unsafe”) to my growing list of values.

This was getting to be as much fun as preparing a tax return!

And just as filling in a tax return isn’t black and white—think of deciding what’s tax deductible and what’s not—I sensed balancing soil contamination and growing edibles had shades of grey, too.

So I set out to see how urban veggie growers can best tackle the question of soil contamination without being mired in conflicting numbers.

What Other Growers Do

Travis Kennedy, an agrologist involved in community garden projects, also raises produce at his Lactuca Micro Farm in Edmonton. “Pragmaculture,” he responds with a laugh, when I ask how he deals with possible soil contamination. His pragmatic approach to urban agriculture is to always use raised beds, bringing in soil he knows is safe, because he always assumes that there may be contamination.

Ward Teulon, also an agrologist, runs City Farm Boy in Vancouver, designing and building vegetable gardens. Teulon explains that sending backyard soil samples to a laboratory doesn’t always give a clear picture of what’s in the soil because urban soils are moved around a lot and are not uniform. He agrees, however, that interpreting results from expensive tests, which can cost hundreds of dollars, can be daunting. If there is a cause for concern, he believes money is better spent bringing in soil to make a raised bed. “Find out your property’s history,” he advises, because many urban soils are perfectly fine.

Luckily for me, my property’s history seems clear-cut, from agricultural to residential.

So, aside from the paint-chip-infested soil beside the house, I’m not worried. Gardeners who don’t know the history of their site could ask neighbours about past use and nearby properties, or check municipal records or archives.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Asssessing the Risk

In 2014, Toronto Public Health created a plain-language guide to help gardeners understand the issues surrounding possible soil contamination and growing edibles.

Josephine Archbold, who helped write the Guide for Soil Testing in Urban Gardens, says it’s wrong to think only experts can figure out when to grow and when to worry.

The guide moves away from the notion that soil is either safe or unsafe—a black-and-white approach.

“I think we need to move beyond the concept of ‘safe’ and ‘not-safe’ cut-off levels that tell gardeners to either garden (100 per cent) or not garden at all (0 per cent),” she says. Instead, the guide is intended to help gardeners think about the risk of contamination for a site, and gives options to deal with the situation. Testing is expensive, and raised beds can be expensive, too, so the guide encourages taking such actions only when the risk of contamination makes them appropriate.

Three-Step Guide

Step 1

Former orchard land is among those sites considered medium concern because of the legacy of old metal-containing sprays.

In the three-step guide, the first step is to establish a level of concern by looking at former land use. With high-concern sites (e.g., former gas stations), contamination is very likely, so the guide recommends skipping expensive tests and using risk-minimizing measures such as raised beds, container gardening, or cultivating fruit and nut trees—for which contaminant uptake isn’t a concern. Nor is soil testing recommended for low-risk sites (e.g., long-term residential areas).

There are medium-concern situations (e.g., hydro corridors and former commercial land) where testing is recommended, but even then, if gardens are smaller than 170 square feet (16 sq. m), raised beds are suggested because the cost of raised beds for such a surface area is likely less than testing. Surprisingly, former orchard land is among those sites considered medium concern because of the legacy of old metal-containing sprays.

After investigating the history of the garden site, another part of establishing a level of concern is physically inspecting soil: dig in a few random spots to see if there are unusual stains or odours, and note old equipment, tanks and debris that might provide clues to dumping. Dumping, burning, smells and staining can make for a high-concern site.

Step 2

When it comes to step two, testing the soil, the guide lists common contaminants, including some metals (such as lead, arsenic and cadmium), along with PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), which Archbold explains are compounds that indicate past industrial activity. “Our soil screening values are specifically for urban gardening,” she says.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Step 3

The third step is to take actions to reduce risk. In keeping with the guide’s approach, the screening values don’t tell gardeners to either garden or not garden. The values help guide the actions of gardeners. For example, if test results or site history present a medium concern, suggested tactics are lowering the level of contaminants by adding clean soil and organic matter. Archbold says adding organic matter makes many contaminants less mobile.

Another example of how to reduce risk is reducing soil dust by covering soil with a mulch, peeling root vegetables before eating and avoiding crops more likely to accumulate contaminants (cabbage family, beets and spinach).

Suspect Contamination?

If you suspect contamination and opt for testing instead of raised beds, containers, or fruit and nut trees, the guide gives pointers about how to find an accredited lab in your area. When collecting soil samples, there are some important steps to follow—and the guide gives instructions for this as well.

As for the strip beside my house, I will plant a fruit tree. I still don’t know how many parts per million lead are in the soil there, but because the site inspection (namely, digging and seeing all those paint chips) points to a possibility of contamination, my guess is that lead levels could be on the high side. It’s a very small space, so I’ve ruled out expensive testing.

I’ve also ruled out a raised bed because I don’t want to redirect water into my neighbour’s yard. So, a fruit tree seems to me to be the most practical approach—and is an acceptable shade of grey for me.

Originally published in Garden Making Magazine, Spring 2014

More Food Gardening Ideas

Library of Articles

Courses

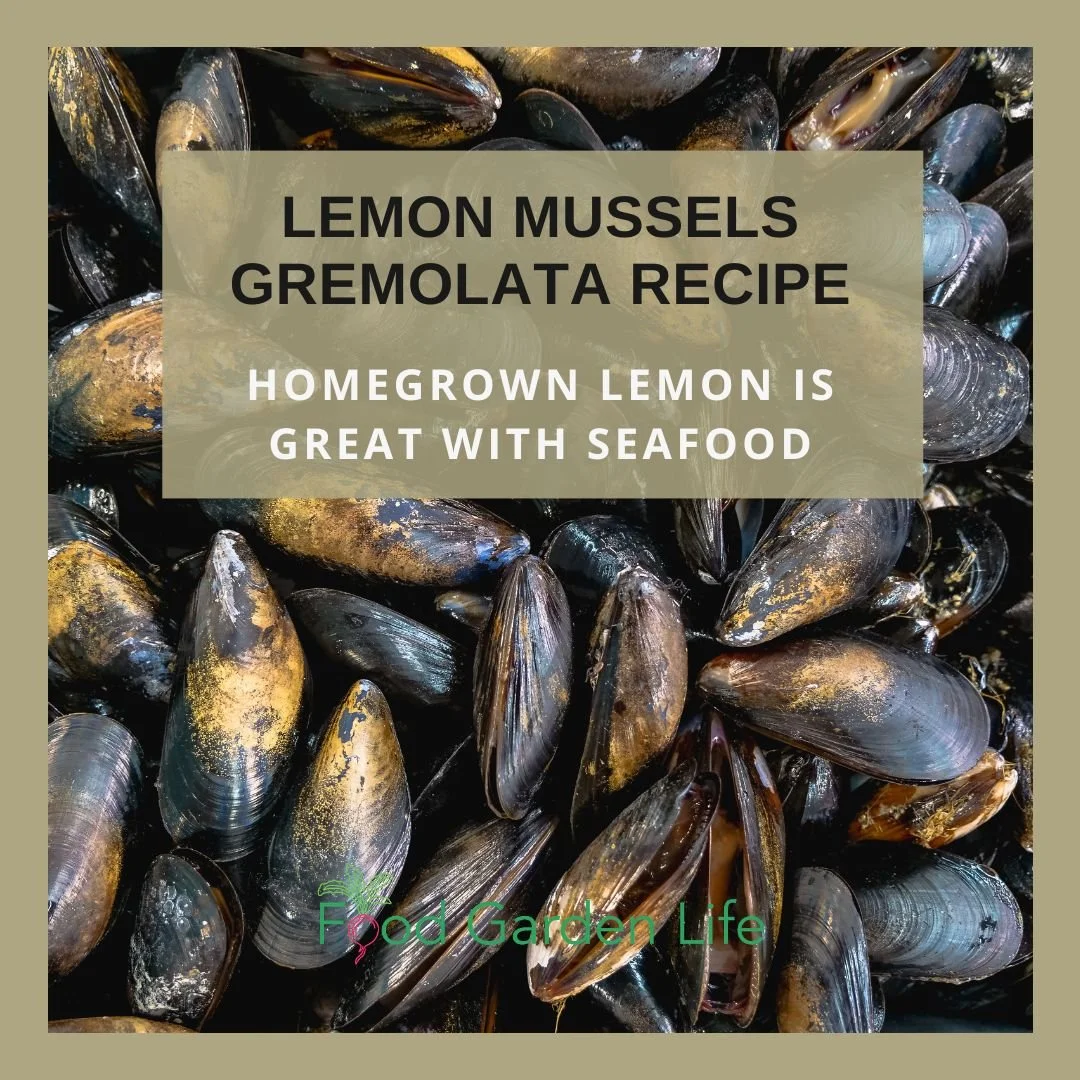

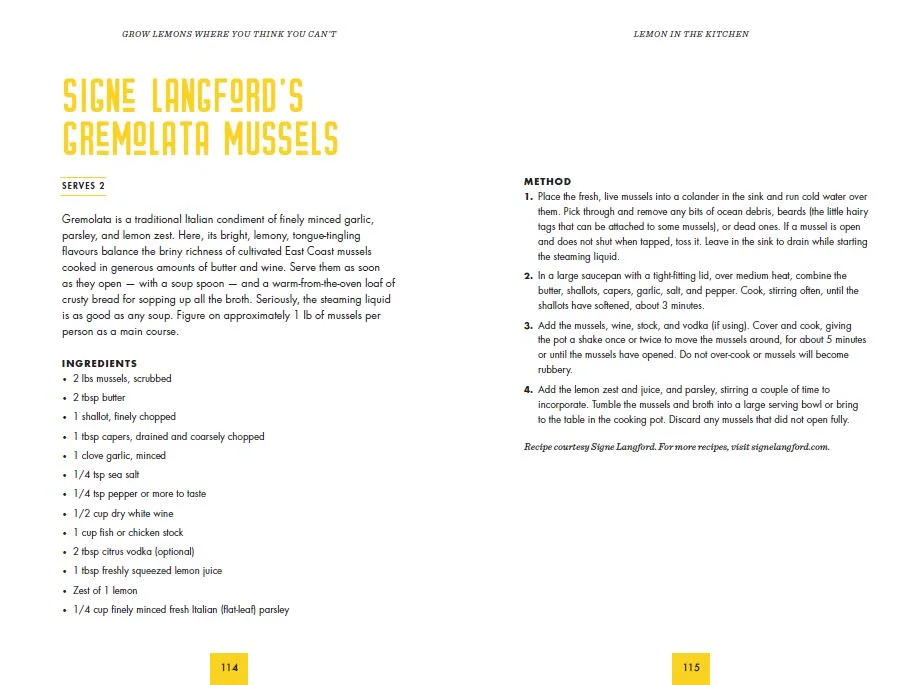

Lemon Mussels Gremolata Recipe

Homegrown Lemon is Great with Seafood

If you are growing a lemon tree indoors and wondering what you will do with your homegrown lemons, here’s a recipe I love and included in my book Grow Lemons Where You Think You Can’t: Lemon Mussels Gremolata.

Thanks to author, storyteller, and chef Signe Langford for sharing this recipe.

And if you’re a gardener, keep in mind that a potted lemon tree is a great addition to the garden. As well as fresh lemons, you get fragrant flowers, and flavour-packed leaves that are very useful in the kitchen!

Lemons: A Perfect Patio Plant

Lemon trees are more cold-tolerant than many people realize, which makes them an ideal potted plant for decks, patios, balconies, and gardens in northern climates. That’s because the cold-tolerance means there are many ways to overwinter lemon trees.

You don’t need a greenhouse or a bright south-facing window indoors!

As well as the fruit, if you grow lemon you will get deliciously fragrant flowers and very aromatic leaves that you can use to flavour all sorts of dishes (I love wrapping lemon leaves around a firm cheese and grilling on the BBQ!)

Read about why lemons are a great choice for northern gardens

6 Reasons to Grow a Lemon Tree in a Cold Climate

Read about how cold lemon trees can get over the winter

Find out more about my book Grow Lemons Where You Think You Can’t

More Lemon Resources

Book: How to Grow a Lemon Tree in a Cold Climate

Course: Grow Lemons

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

What to do with Pumpkins After Halloween (and a Pumpkin Recipe!)

By Steven Biggs

Cook (or Compost) Your Pumpkins Too!

The first pumpkin is carved for Halloween this year; the kids had a pumpkin-carving get-together with friends over the weekend. That only leaves three giant pumpkins, four pie pumpkins, a warty pumpkin, a Jamaican pumpkin, a Turk’s turban squash, a blue hubbard squash, and an elongated pinkish pumpkin. Guess what we’re doing tomorrow!

We’ve hit a pumpkin-carving crescendo this year. The kids are the right age to design and carve. I love it as much as my they do. (To my imagination that blue hubbard squash looks a bit like a turkey in a roasting pan…)

Did we go overboard with so many pumpkins and squash? No.

Pumpkins make their way into our kitchen, or into our soil. We eat them or compost them.

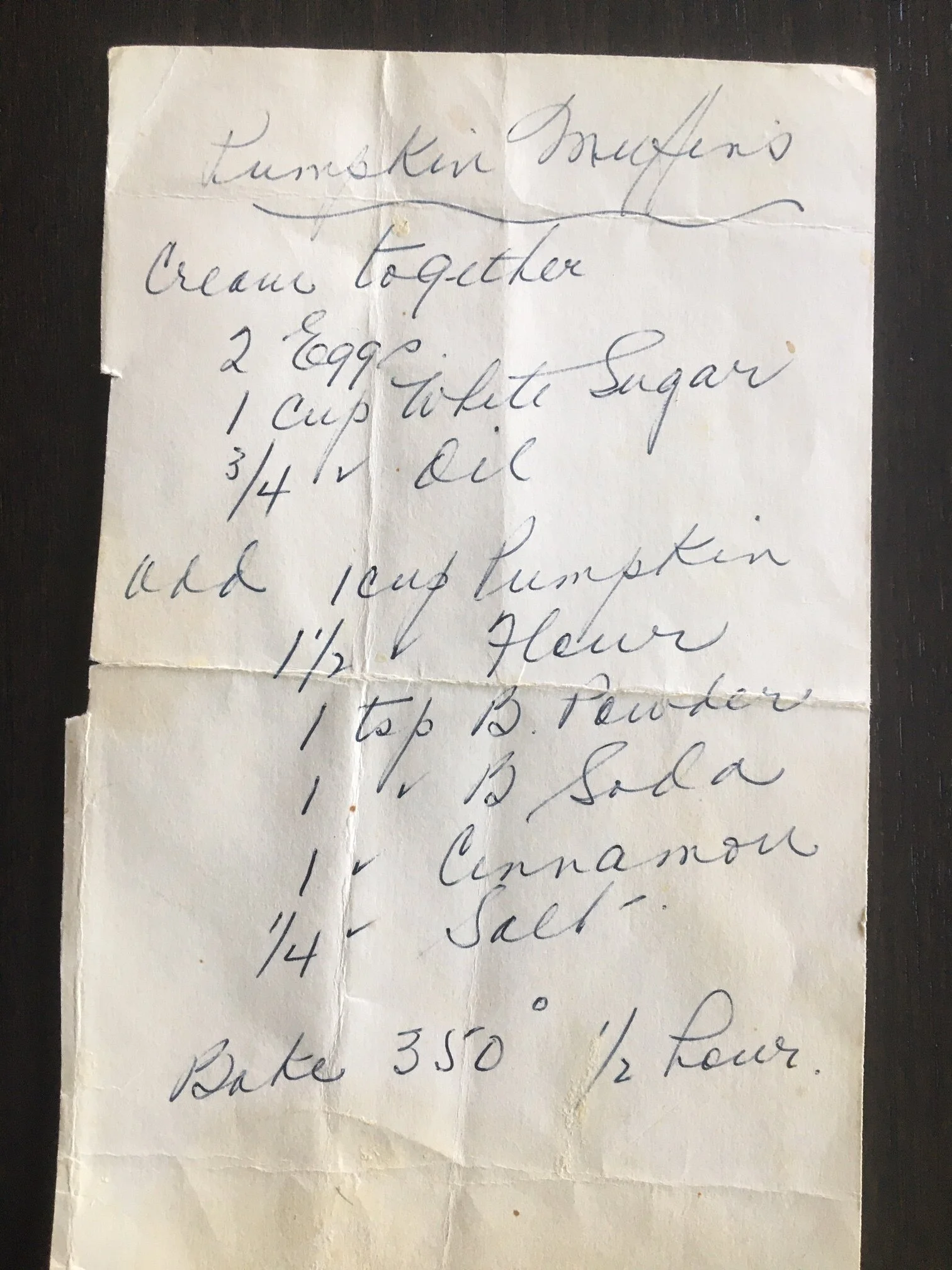

Pumpkin Muffins

Nana Biggs’ pumpkin muffin recipe. (I usually cut the sugar in half and add raisins and nuts.)

One of Nana Biggs’ favourite recipes was pumpkin muffins. I remember as a kid taking my jack-o-lantern there the day after Halloween so that Nana could roast it.

(My Uncle Bill didn’t agree with my giving Nana all of that pumpkin as he didn’t care for the supply of muffins encouraged by it. I never let him forget that. One fall after I had moved away from home, I roasted a jack-o-lantern, baked a giant, six-inch-wide muffin, and sent it to Uncle Bill by courier.)

My kids all like pumpkin muffins, so Nana would be pleased. They love roasted pumpkin seeds too. (A bit of oil, salt, and garlic powder makes a mean roasted pumpkin seed, in my opinion.)

Last year, my wife, Shelley, spent a whole day roasting various pumpkins and squash, and made a series of pies, using different proportions of each. We got to taste-test them all. There were lots more that went into the freezer. We just ate the last one yesterday.

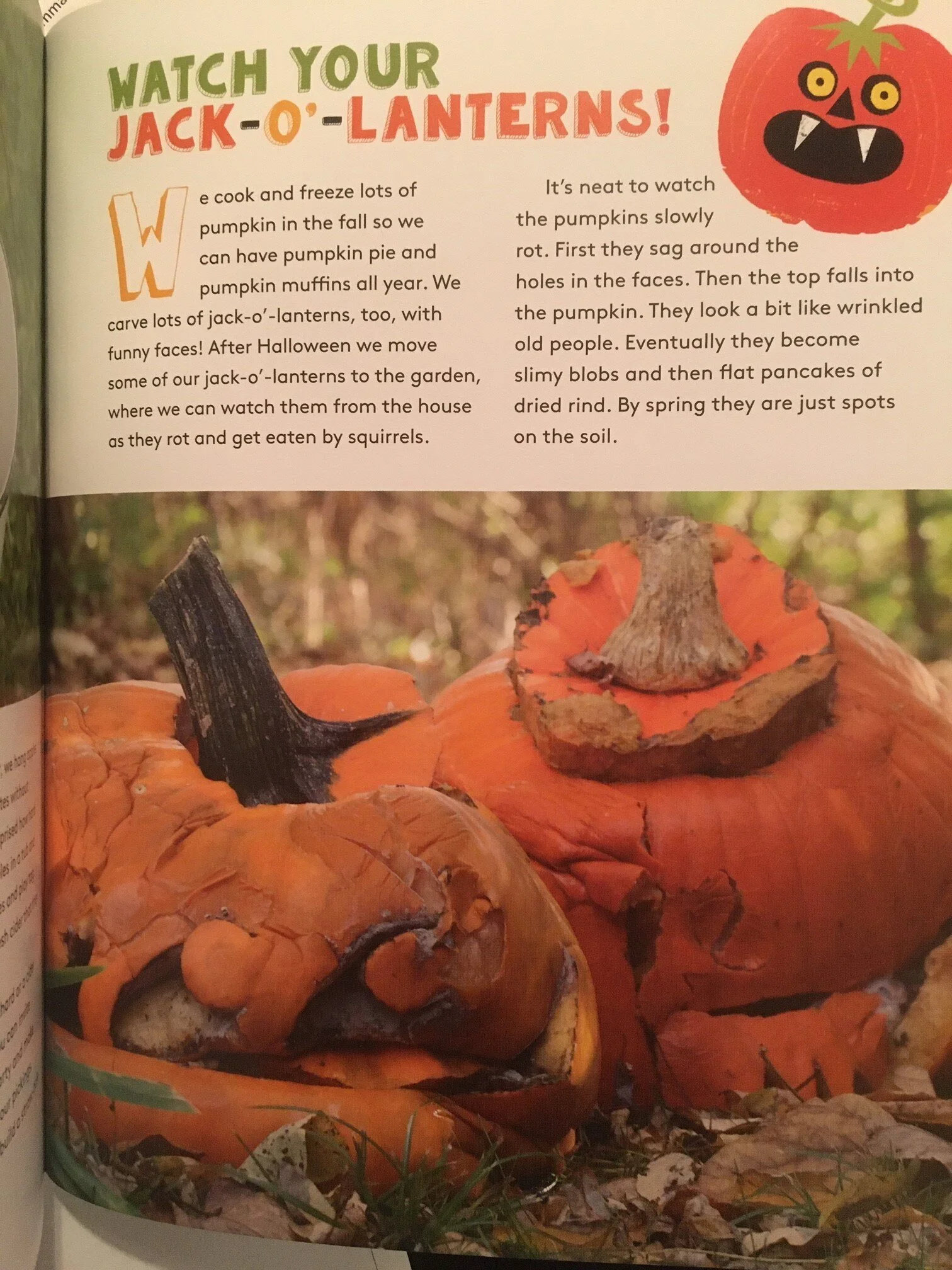

Watch Your Jack-O-Lanterns!

You must be wondering if we’ll eat all of those pumpkins on our front porch this year. We’ll use the pie pumpkins first, as they have a less watery, more flavourful flesh.

What doesn’t go into pumpkin pies, muffins, and soups feeds the soil.

My daugher Emma shares this idea in her book Gardening with Emma.

Sometimes we put our jack-o-lanterns in the compost pile. But what’s really fun is watching them slowly melt into the soil.

Each one ages differently!

In my daughter Emma’s book, Gardening with Emma, she tells kids how pumpkins in the garden start to sag, and then become spots on the soil by spring.

Written for kids by a kid, this guide helps kids see the fun side of gardening, whether it’s growing giant vegetables, making a bug vacuum, or making a sound-themed garden.

Emma shares lots of inspiring ideas for young gardeners about how to grow healthy food, raise cool plants, and have fun outdoors.

Copies from the Food Garden Life shop are signed by Emma!

Meyer Lemon Sorbet Recipe

By Steven Biggs

Meyer Lemon Zest is a Big Part of this Sorbet

If you are growing a Meyer lemon tree and are wondering what to make, here’s a great way to enjoy the unique flavour of Meyer lemons: Meyer Lemon Sorbet.

I included this family favourite in my book Grow Lemons Where You Think You Can’t: We make it using our own homegrown lemons.

This recipe uses both the juice and the fragrant zest.

If you’re growing other citrus, you can use this same recipe to make your own sorbet. For sweeter citrus, you might want to use a bit less sugar. For other citrus such as yuzu, you might add a bit more sugar.

Find out more about yuzu, a fragrant citrus that’s a great container plant for a home garden.

Looking for More Lemon Ideas?

Here’s another lemon recipe: Mussels Gremolata with Lemon.

For more recipes and information about growing potted lemon trees in cold climates, go to the Lemon Home Page.

More on Growing Lemons

If you want to grow a potted lemon tree (that actually fruits) in a cold climate, below are a couple more resources to help you on your journey. I grow lemons and other citrus here, in Toronto, Canada. (My oldest potted lemon tree is from 1967!)

Book: Grow a Lemon Tree in a Cold Climate

Course: How to Grow a Lemon Tree in a Cold Climate

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

Watering Lemon Trees

By Steven Biggs

Watering is the #1 Issue for Lemon Trees

In this excerpt from my book Grow Lemons Where You Think You Can’t, I talk about watering lemon trees:

How often you water your lemon depends on your soil mix, pot type, pot size, plant size, the weather, and if the plant is growing or dormant.

“I consider overwatering to be the number one issue,” Bob Duncan says as we chat about the problems he most often sees with lemons.

If the soil is constantly soggy — lemons hate soggy soil — the roots rot, which will eventually kill the plant.

How Much Water?

Watering is the number one issue for lemon trees.

When watering a potted lemon, apply enough water so that water comes out the drainage holes at the bottom of the pot — that’s when you know you have given it enough water. The other benefit to having water come out of the drainage holes at the bottom is that this also flushes out excess salts.

Another important watering consideration is that the lower soil in the pot remains more wet than the soil at the top — something you won’t be aware of unless you take the plant out of the pot. Don’t decide to water based only on how dry the top of the soil feels. Looks can be deceiving.

You want to give the plant time to use up the moisture in the bottom of the pot but not leave it to the point where the soil is too dry.

Once you get the hang of it, it’s not difficult. The following considerations will help you decide if it’s time to water:

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

Knowing When to Water

In the summer, when the lemon is growing, it will need regular watering.

Your lemon will still need some water in the winter, even if it’s not growing much. That’s because lemons are evergreen — they keep their leaves — so the plant will continue to lose some water through the leaves. (If you upset them, however, they might drop their leaves.)

I like Bob’s watering lingo for lemons stored in a cool place over the winter: “Keep them on the dry side of moist.”

If the pot is small enough, with a little practice you’ll be able to tell if your lemon needs water just by picking it up and feeling the weight of it.

If in doubt, stick your finger into the soil.

Don’t forget: The type of pot that you have affects how often you have to water. Soil in unglazed terracotta pots dries out more quickly than soil in plastic pots.

In summary: Don’t water a little bit each day!

More Lemon-Growing Information

Lemons: Articles and Interviews

Drop by the lemon home page for more articles and interviews to help you grow lemon trees at home.

Here’s a chat with a lemon expert to help you grow more lemons:

Lemons: Book on Lemons in Cold Climates

How Cold can Lemon Trees Get?

By Steven Biggs

Overwintering Lemon Trees

There are many ways to overwinter lemon trees, because they tolerate colder temperatures than many people realize.

In the picture below, I’ve loaded up a potted Meyer lemon plant to move into a protected area for the winter.

In the beginning, I used to grow it in the kitchen all winter.

Then, I started leaving it in the dark, cold garage for the winter.

These days, I put it in a greenhouse that I keep just above freezing.

Wondering what to do with a potted lemon tree for the winter? In this excerpt from my book Grow Lemons Where You Think You Can’t, I talk about how cold-hardy lemon trees are.

MY LEMON TREES DID VERY WELL when I moved into a house with an old sunroom that stayed just above freezing in the depth of winter.

There are many options for overwintering lemon trees in cold climates because they tolerate cold.

Sadly (for me), the dilapidated sunroom succumbed to a house renovation and my precious lemons were banished to an insulated garage for the winter. Normally, I kept an electric heater in the garage that I could flick on if the temperature plummeted.

But while we renovated, there was no power to the garage, and during a particularly cold spell, the temperature inside the garage dropped well below freezing.

I was heartbroken to think I’d lost my lemons.

Happily, they survived. Only a few branch tips died. For plants that I associated with Mediterranean climates,

I was delighted to learn that lemons are amazingly cold tolerant!

Many factors determine cold hardiness

It’s not an exact science.

For example:

Young plants are more tender.

Fruit and young shoots will be affected before older, woodier stems.

If the plant is already dormant from cool temperatures, it can better withstand cold than an actively growing plant.

With grafted lemon plants, some rootstock are more cold-tolerant than others.

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

Citrus expert Bob Duncan of Fruit Trees and More on Vancouver Island says to remember the temperature at which the fruit freezes.

The MOST Important Temperature to Remember

When I asked citrus guru Bob Duncan from the nursery Fruit Trees and More about lemon hardiness and minimum winter temperatures, he stopped me and took me back a step, saying:

“With lemons the fruit is on the tree in the winter. The question to ask is ‘What temperature does the fruit freeze at?’”

Bob went on to explain that the fruit of citrus is at risk at anything below -3°C (27°F).