How to a Grow a Mulberry Tree

How to grow mulberry in cold climates.

By Steven Biggs

Fowling in Love with Mulberry

My neighbour Hubert handed me a pheasant and a duck from his freezer. I was working for the summer in a rural part of the UK, and regularly saw pheasant when I went out for a jog. Now I’d get to taste one!

As a 20-something-year-old, I’d never cooked either before…and had never even tasted pheasant.

But I remembered reading that the meat is rich and dark, well-suited to a tangy accompaniment.

And I remembered a mulberry tree in a nearby hedgerow.

I’d been grazing fruit from the mulberry tree every time I walked past it. But I had yet to cook the mulberry fruit.

This was my chance! Not really sure what I was doing, I made up a mulberry-Cointreau sauce for basting the roast. The company I had for supper thought it was pretty good.

Roasted fowl with mulberry-Cointreau sauce cemented my appreciation for the taste of mulberry.

Mulberry for Home Gardens

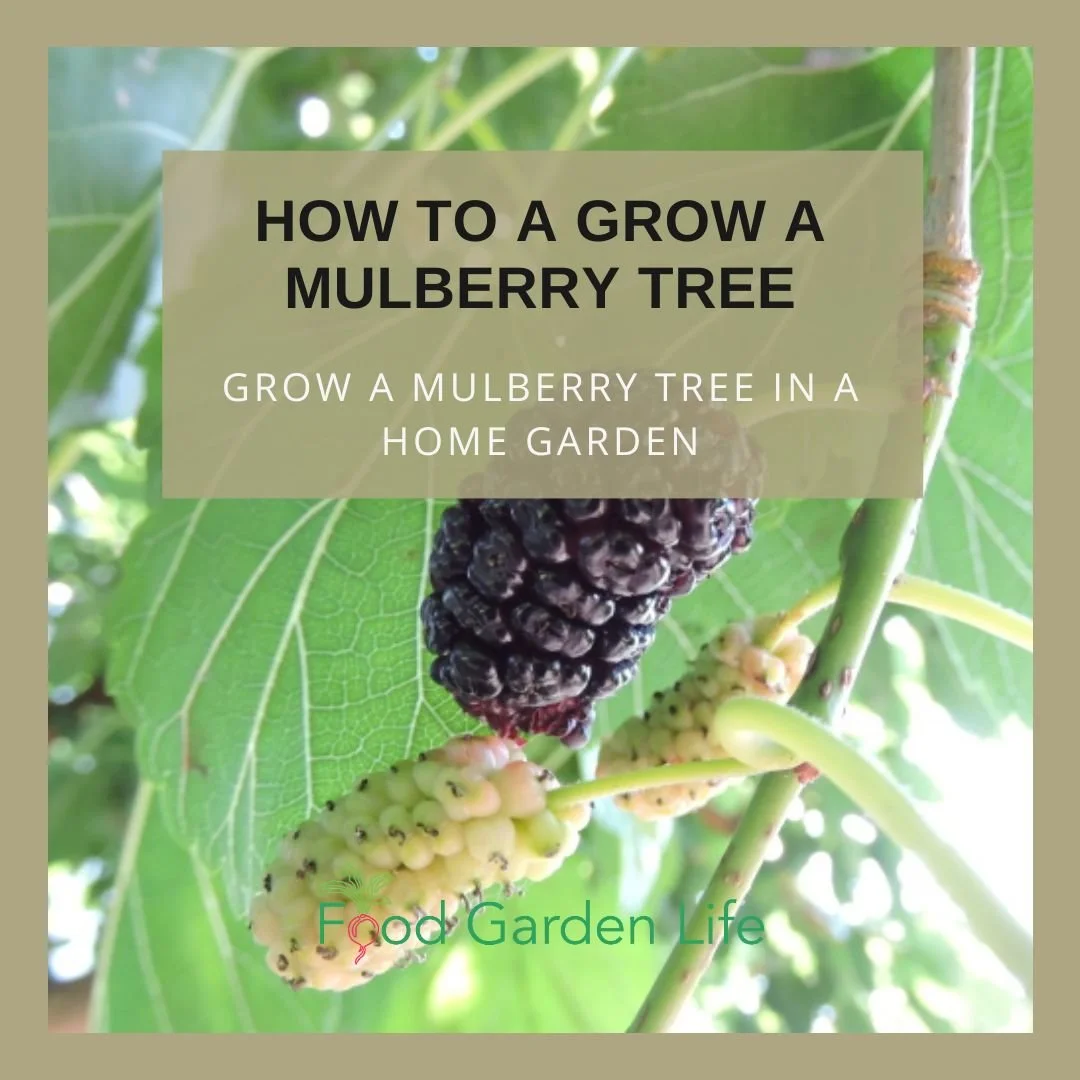

There are many types of mulberry suited for gardens in cold climate. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

Mulberries gets a bad rap. Mention mulberries and many people picture polka-dot-stained sidewalks and bird-bespattered cars. Or experienced gardeners worry that it’s a weedy plant.

Why is it that gardeners always want what’s difficult to grow? Why not appreciate what grows on its own?

This fruit does not play hard-to-get.

Mulberry is a great fit for home gardens because it’s:

Fast-growing

Hardy

Problem-free

Tolerant of many conditions

Very fruitful

And it’s a fruit that you likely won’t find for sale at grocery stores. Too fragile to ship when ripe.

Too bad mulberries get a bad rap for being vigorous growers.…and for the purple stains from falling fruit. They’re a great fruit for home gardens in cold climates.

What does a Mulberry Tree Look Like?

What does it look like? The question should really be, “What does a mulberry tree look like when pruned to feed people, not birds. (More on that below.)

Don’t grow this as a specimen shade tree. There are nicer shade trees out there.

Grow mulberry as a fruit-producing crop – which means you’ll keep it much smaller than if left unchecked.

Types of Mulberry for Cold Climates

Mulberry names don’t describe the fruit colour. That means a white mulberry tree could be black-fruited, red-fruited, or white-fruited.

If you’re shopping for a mulberry tree, here at the three types you’re likely to find in North America:

• White mulberry (Morus alba)

• Red mulberry (Morus rubra)

• Black mulberry (Morus nigra)

Mulberry names don’t describe the fruit colour. While this ‘Carman’ white mulberry fruit is white, other white mulberry varieties can be purple or black. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

For cold-climate fruit growers, it’s the white mulberry and its hybrids with the red mulberry that are hardiest, some into USDA zone 4.

I’ve read articles in British gardening magazines that disparage the less flavourful white mulberry…but it’s what we have.

White mulberry can grow up to about 15 metres (50’) tall. Because it grows easily from seed—and because birds quickly spread the seeds—feral white mulberry trees are common. (It’s considered a weed tree in some jurisdictions.)

Red mulberry is a native of North America. Pure red mulberry trees are rare because feral white mulberry and red mulberry hybridize readily. Here in Ontario, where red mulberry is native in the south of the province, its threatened by the white mulberry due to their promiscuous hybridizing.

The more diminutive black mulberry, noted for the quality of its fruit, is less hardy, and not suited to northern gardens. It’s suited to conditions in USDA zones 6 and higher.

Other thoughts on selecting a mulberry tree:

There are weeping varieties that get to about 3 metres (10’) tall and can be perfect for small-space gardens (just beware, as there are fruitless varieties of weeping mulberry on the market)

There are dwarf varieties that get to about 6 metres (20’) tall

White-fruited varieties might be the ticket is you’re averse to mulberry stains

‘Illinois Everbearing’ is noted for having a long season of fruiting

Plant a Mulberry Tree

Mulberry trees fend for themselves quite well once established, but here are things you can do to give them a good start.

If you’re planting a container-grown mulberry tree, the first thing to do is look at the roots. Because mulberry is a vigorous grower, it’s common to find roots tightly wound around and knitted together.

Use your fingers to tease apart the roots. We want the roots to grow outwards into the surrounding soil once planted, not continue to grow around in circles.

Water well when first planted and until established.

Pruning Mulberry Trees

Many sources suggest that regular pruning is not necessary with mulberry.

That’s fine if you want to feed the birds.

But if you’re growing the mulberries for yourself, I suggest a different approach: Be aggressive – and do it every year.

Your goal is to create a permanent scaffold of branches that you cut back to every year (see below).

Formative Pruning

Grow mulberry trees in an umbrella shape, so you can reach all of the fruit. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

The best way to get a tree with a well-arranged scaffold is to make it yourself. Get a whip, which is a young, unbranched tree. (You probably won’t find this sort of tree at a garden centre; look for a specialist fruit-tree nursery.)

Then prune that whip so that it grows into a spreading tree. Think short and wide.

Start this pruning process by removing the “leader,” which is the growing tip of the tree. Linda Grimo, at Grimo Nut Nursery, a specialist nursery, suggests, “Stand as tall as you can with your pruners in your hand and clip off the top of the tree.” She explains that this stops it from growing upwards, and encourages the growth of side branches at a height you can reach without a ladder.

Umbrella-shaped mulberry tree in summer. Prune hard to keep berries at picking height. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

Grimo says she likes to grow mulberry trees in an umbrella-shaped scaffold, with side branches (laterals) spaced out around the tree. For ease of getting under the tree to pick, don’t grow the side branches too low on the tree; her preferred height is just over a metre (4’) above the ground.

Annual Pruning

Mulberry trees growing in good soil put on a tremendous amount of growth every year. After formative pruning is complete, prune back almost all of the new growth every year, leaving just 1-2 buds from which the tree can send up replacement shoots.

This harsh pruning doesn’t affect cropping because fruit forms on new growth. “Don’t be afraid, you can’t kill a mulberry tree,” is what Grimo tells concerned first-time mulberry growers.

Prune in late winter, when dormant.

Mulberry Tree Feed and Water

Mulberry trees have extensive root systems, which means that they can do quite well without coddling.

Mulch with compost around the base of the tree to feed the soil and suppress weed growth.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Mulberry Tree Pollination

Mulberry trees are self-fertile, which means you only need one tree to get fruit.

The small, unremarkable flowers are wind pollinated. (There are even some varieties that set fruit without pollination.)

Mulberry Tree Propagation

Dwarf or weeping mulberry varieties are well-suited to use in small-space foodscapes, even in more traditional gardens.

Mulberry plants grown from seed will be different from the parent plant. Just like apples. There is a juvenile period before a seed-grown mulberry tree will flower and produce fruit, often 5-10 years.

It’s easy to grow from seed. In fact, this is a tree that might just seed itself in your garden.

I don’t recommend growing mulberry from seed, because you don’t know what the fruit quality will be like—and you’ll have to patiently wait through that juvenile stage.

Another unknown if growing from seed: Some mulberry trees are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are on separate plants…and that could leave you with a tree that doesn’t bear any fruit.

If you want good fruit quickly, start with a known variety. Clonally produced trees—grafts and cuttings—can fruit right away because the clone is from a mature tree, and no longer in the juvenile stage.

Some nurseries propagate mulberry by cutting, some by grafting. For grafting, Grimo says cleft grafts work well. Propagation from cuttings can be more challenging for home gardeners without a misting system, bottom heat, and rooting hormone.

Mulberry Trees in Garden Design

Mulberry trees are quite versatile in garden design. Here are ideas for using mulberry trees in the landscape:

Dwarf or weeping varieties are well-suited to use in small-space foodscapes

Large, minimally pruned mulberry trees can be used for a canopy layer in a food forest

Smaller mulberry varieties can fit a forest-edge niche in a food forest because the tree tolerates partial shade

From a permaculture perspective, mulberry is an interesting option because along with fruit, it can provide poles and animal fodder (see below)

Mulberry for More than the Fruit

Because it grows very quickly, mulberry is well suited to pollarding and coppicing techniques. Here are branches from my neighbour’s mulberry pollard that I use as poles in the garden.

Mulberry is an excellent tree choice if you’re gardening with a permaculture mindset.

My neighbour Troy used to give his mulberry tree a harsh haircut every year. The long, straight branches made excellent poles that he gave me for staking plants and making trellises.

He grew his tree as a “pollard,” meaning he lopped off all of the growth a few feet above the ground. (Pollarding is often done with catalpa trees, for ornamental purposes.)

The other twist on this idea of using your mulberry tree to produce poles, is to grow it as a “coppice.” Coppicing is when you cut off a tree close to the ground to get it to send out lots of stems. Coppicing has traditionally been used to produce wood for baskets, fences, and fuel.

Mulberry Tree Location

Mulberry trees prefer full sun and rich soil. But they tolerate partial shade and a variety of soils.

And much worse.

To say they’re forgiving of poor conditions is an understatement.

I’ve seen lovely mulberry trees growing between cracks in the pavement. They do amazingly well in inhospitable locations. As I write this I’m looking out the window at the self-seeded mulberry tree in my front garden that I’m training into an espalier. It’s growing right underneath a row of spruce trees, hardly an ideal location. But it persists!

So save the prime real estate in your garden for plants that really need it. Your mulberry isn’t fussy. And, remember, pick a spot where purple spotting is not a nuisance.

The one thing to avoid is standing water. Pick a well-drained location, though occasional wetness is fine.

Challenges

Your mulberry tree will be a bird beacon.

Got a white car? Hanging out clothes to dry?

Then you might want to net the tree to keep away the birds. Netting is easier to do when you’ve grown a compact mulberry tree.

Harvest and Store Mulberries

If you’ve started with a tree grown from a graft or cutting, you might start getting fruit in as little as 2-3 years.

Not all the fruit on a tree ripens at the same time. As they ripen, fruit fall to the ground.

White mulberries can be very sweet, while black mulberries are more balanced, with some tartness. I prefer white mulberries a little bit under ripe—while they’re less sweet. (Remember, a white mulberry tree can have black fruit!)

A couple notes on picking mulberries:

The fruit are fragile, and the juice easily comes out of the fruit when picked…so expect red hands if it’s a dark-coloured variety

Ripe fruit will drop from tree as you pick

A common recommendation when harvesting from large mulberry trees with many unreachable fruit above is to place a sheet on the ground and shake the branches.

The fruit has a short life once picked. There’s a little stem on it – and you can eat it stem and all.

Here are 6 simple ideas to grow lots of fruit in a home garden.

Mulberries in the Kitchen

You can use mulberries raw, use them in preserves, or cook them. Here are ideas:

Mulberry pie

Mulberry wine

Mulberry cobbler

Mulberry liqueur

Dried mulberries (great in a trail mix!)

Mulberry juice

Mulberry FAQ

How fast do mulberry trees grow?

Mulberry trees grow very quickly.

Where do mulberry trees grow?

White mulberry and its hybrids are suited to cold-climate gardens into USDA zone 4. Black mulberry is less cold-tolerant.

Can you grow a mulberry tree from a cutting?

Yes. You can grow mulberry trees from cuttings.

Do mulberries grow on trees or bushes?

Mulberries naturally have a tree form, but you can prune to encourage branching and a bush-like shape.

Can you grow a mulberry tree in a pot?

Cold-climate gardeners who are determined to try black mulberry can grow it in a pot that is stored in a protected area over the winter.

How do you keep a mulberry tree small?

Prune it very aggressively every year.

Do mulberry trees grow near black walnut trees?

Mulberry trees are not affected by the compound “juglone” that is given off by black walnut trees. So if a black walnut tree has limited your growing options, consider mulberry.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Fruit

Get our free guide with 6 ways to grow more fruit in your garden.

Articles and Interviews about Growing Fruit

Here are more resources to help you grow fruit.

Courses on Fruit for Edible Landscapes and Home Gardens

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Guide to Growing Nanking Cherry: An Easy-to-Grow Bush Cherry

Guide to growing Nanking Cherry, an easy-to-grow cherry bush.

By Steven Biggs

Grow Nanking Cherry

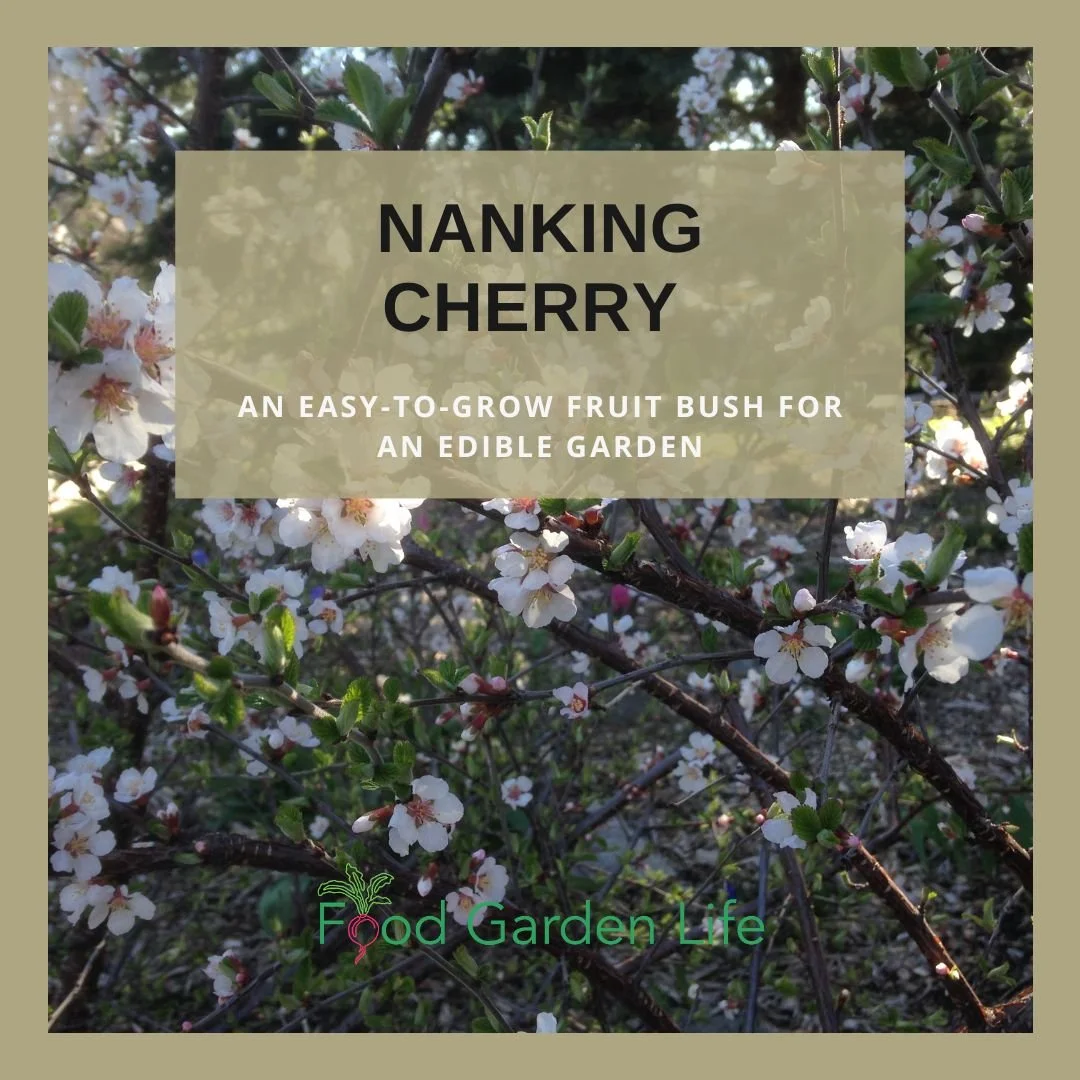

The Nanking cherry bush has a spectacular bloom early in the spring.

“Dad, someone’s taking a picture of your garden,” shouts one of the kids. It’s early May, so I know which plant will be in the photo.

The Nanking cherry, a.k.a. Prunus tomentosa. Even though our front garden is a party of spring flowering bulbs, when the Nanking cherry is blooming, it steals the show.

The Nanking cherry bush is like a stop sign. Pedestrians going past our house change gears from a brisk walk to a full stop and then take photos.

Spring isn’t the only time it looks great: it looks great again as the fruit colours up. And unlike cherry trees, where you have to look upwards, this cherry bush is at eye level.

Perfect Fruit for a Home Garden

Nanking cherry is ideal for a home food garden because it’s compact, ornamental, and easy to care for. By comparison, many fruit trees require a fair bit of pruning and pest and disease management. And they take more space.

The small, bright-red cherries are juicy. I’d place the taste somewhere between sweet and sour cherries.

Where to get Nanking Cherry

Nanking cherry flower buds

When I teach about edible landscapes, most students haven’t heard of Nanking cherry because it’s not too common in the horticultural trade. It’s a pity because this is such a fantastic home garden fruit bush.

Look for a nursery specializing in fruit and cold-hardy plants. Or, better yet, find somebody who is already growing it, because many of the seeds that drop around the bush will grow.

(I once mentioned this to my class and was asked by students if that meant I had extras to share. I did. And I took in a tray of small cherry bushes the following class.)

By Seed

While many fruit trees and bushes are propagated commercially by cuttings or grafting, Nanking cherry is commonly seed grown. You can grow them from seed at home:

Look for small Nanking cherry plants growing from seed near a mature, fruit-bearing bush.

When saving seeds to grow, don’t let them dry out too much

In the fall, place seeds in damp potting soil

Store potted seeds in a cold location until spring (a fridge or animal-free shed or garage is fine)

In spring, watch them grow!

When you grow from seed, the seedlings will all be genetically distinct, so expect some variability between plants. Seed-grown plants often flower in less than five years.

Cuttings

If you have a Nanking cherry plant that you really like, you can also propagate it from cuttings. Root softwood cuttings in early summer, as fruit ripens, or root cuttings from dormant hardwood in the spring. High humidity and rooting hormone increase the percentage of cuttings that root.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Layering

Another way to propagate Nanking cherry is by layering. This is the practice where a low-lying branch is covered with soil until it grows roots and can be detached from the main plant. I find it’s often enough to simply to pin a low-lying branch to the soil by covering it with a brick.

Nanking Cherry Varieties

Red-fruited, white-flowered varieties of Nanking cherry are the most common in the horticultural trade.

There are not a lot of improved varieties available commercially. At the time of writing this, I’ve just ordered one called ‘Pink Candles.’

Along with the common seed-grown, white-flowered, red-fruited Nanking cherry varieties, look for:

White-fruited varieties

Pink-flowered varieties (like ‘Pink Candles, above)

Cold-Climate Cherry

If you’re gardening in a cold zone, Nanking cherry withstands cold winters and hot summers. My grandfather grew Nanking cherry in Calgary, a mercurial climate if ever there was one. His cherry bushes soldiered on through snow in summer and balmy winter chinook winds.

(Incidentally, he also made wine from Nanking cherry, although I was too young at the time to partake!)

Cold hardiness is never an exact science as there are many variables. But this is a very cold hardy plant, surviving winter temperatures as low as -40°C (-40°F).

Pick a Location for your Nanking Cherry

Sunlight: Full sun is best. As with many crops, if you only have partial sun, it’s worth a try. You’ll still likely get something.

Soil: Well-drained soil, enriched with compost.

Snow load: Winter snow coverage is, if anything, helpful, as it insulates the bush. I have one next to my driveway, and it’s covered every year with heaps of snow.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Prune Nanking Cherry

One of the things that makes fruit bushes far more suited to home gardens is that the burden of pruning is less. You can prune annually if you want – and you’ll be rewarded with a nicer form and more yield. But if you’re busy and don’t get around to it, that’s fine too.

Timing: Prune in late winter.

Size: Remember, as the gardener, you decide the final height of your Nanking cherry bush. Depending on the growing conditions, it will get to 1.5 – 3 metres high (5 – 10 feet). Bushes can get fairly wide if space permits.

I keep mine pruned to about 1.5 metres (5’) high. That’s because I don’t want it to block the sight line between my garden and the sidewalk. And another important consideration is not to let the bush get any higher than you can pick!

In general, pruning that encourages young branches encourages more fruit. Keeping the canopy open with pruning helps to minimize the chance of any diseases because there is good air circulation. Pruning tips:

Remove some of the older branches

Trim out dead branches

Cut out crossing branches

Prune to shorten the bush

Nanking Cherry Pests and Diseases

Nanking cherry is in the same family as cherries and plums, which are affected by a number of pests and diseases. But I’ve never found the need for pest or disease control.

The one challenge I occasionally encounter is branch dieback where leaves on a branch dry up, and the branch eventually dies. Some sources attribute this to fungal diseases. For dieback, prune affected branches back to the main stem.

Harvesting Nanking Cherries

We eat lots of our Nanking cherries right in the garden! But they are versatile in the kitchen too.

Nanking cherries are an early summer fruit. Around here, that means that I’m picking them around the same time as strawberry season is finishing up.

Unlike sweet and sour cherries, where the stem is left attached to the fruit when picked, the stubby little stems on Nanking cherry stay on the bush. As a result, the fruit don’t last as long as other cherries.

Nanking Cherry in the Kitchen

The kids and I sometimes stand around a bush and guzzle cherries and then see who can spit the seeds the farthest. And that’s an important point I should make: like all cherries, there’s a pit!

Use Nanking cherries for whatever recipes call for sour cherries. I also freeze some for winter use. Because of the size, they are a bit fiddlier to pit than larger cherries.

Here are ways we enjoy using Nanking Cherry:

Nanking cherry juice

Nanking cherry compote

Nanking cherry bump (not for the kids!)

And…one other food related idea: I consider cherry wood the finest wood for smoking meat. So when I prune my Nanking cherry, I keep the branches to use for smoking.

Nanking Cherry FAQ

Do I need more than one Nanking cherry bush?

Many sources report the need for two bushes for cross pollination. I started out with one bush – the only one in the neighbourhood – and had good fruit set. There are reports of some self-fertile varieties.

When should I move my Nanking cherry bush?

The best time to move it is in the spring, while it’s still dormant.

Can I grow my Nanking cherry bush in shade?

It will grow best in full sun, but can grow respectably well in part sun/shade. Just know that you probably won’t get as much fruit as you would if it were growing in a full-sun location. As home gardeners we don’t always have perfect conditions.

Can I grow my Nanking cherry in a wet location?

Well drained soil is best. If the water table is high, consider growing in a raised bed.

What about animal pests eating the Nanking cherries?

The birds will like them just as much as you do. But unlike large tree fruit, such as apples and peaches, there’s much more to share when we grow small-fruited crops such as cherries.

Should I cover my Nanking cherry if there’s a frost?

The flowers are early in the season, when the risk of frost is still high. Most years I still get good fruit set here in Toronto. I’ve had reduced fruit set caused by a freeze once in a dozen years.

Is there a Nanking cherry tree?

Nanking cherry naturally grows as a bush.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Cherries

Find out about 5 Types of Cherry Bush to Grow in Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

Hear Dr. Ieuan Evans talk about the Evan’s Cherry

More on Growing Fruit

These Courses Can Help you Grow Your Own Fruit

Edible Native Plants...and My Quest for a Rare Toronto Persimmon Tree

Native North American Fruits and Nuts (including persimmon and pawpaw!)

By Steven Biggs

Ontario Native Edible Fruits and Nuts

Pointing to two trees, Tom Atkinson explains that we have the makings of a golf club.

“There you have the shaft of the club; here you have the head,” he says, pointing from one tree to the other:

The shagbark hickory, with a bit of give in the wood, is ideal for the shaft.

The American persimmon, as part of the ebony family, has extremely hard wood that is suitable for whacking the ball.

Both are native North American species; and both have edible parts.

Hunting Pawpaw and Persimmon in Toronto

Our tree trek today is the result of my interest in another North American native, the pawpaw tree.

Because of my fascination with pawpaw, I tracked down Atkinson, a Toronto resident and native-plant expert, whose backyard is packed with pawpaw trees.

After I visited his yard and soaked up some pawpaw wisdom, he mentioned a fine specimen of American persimmon growing here, in Toronto.

I took the bait.

Under a Toronto Persimmon Tree

Now, in the shadow of that persimmon tree, I’m learning far more from Atkinson than persimmon trivia:

The nut of the shagbark hickory, a large native forest tree, is quite sweet.

He points to a pin oak, explaining that the leaves are often yellowish here in Toronto, where such oaks have trouble satisfying their craving for iron.

Waving toward a couple of conifers, Atkinson explains that fir cones point upwards, while Norway spruce cones point down.

There’s stickiness on the bud of American horse chestnuts, but not on their Asian counterparts.

And while the buckeye nut is normally left for squirrels, he’s heard that native North Americans prepared it for human consumption using hot rocks.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

A Backyard Native Fruit Food Forest

In his own garden, Atkinson’s focus is on native trees and shrubs. Many of them are considered Carolinian and are, here in Toronto, at the northern limits of their range.

My own interest in native trees and shrubs has gustatory motivations, but Atkinson’s came about because of his woodworking hobby. “I thought, if I was using wood, I should be putting it back,” he explains. While no longer woodworking, he still has a garden full of native trees and shrubs.

The edible native North American fruit and nut trees in his backyard food forest include sweet crabapple, black walnut, bitternut hickory, red mulberry and beaked hazelnut. “It is really for the creatures of the area, all this bounty,” he adds. I’m taken aback by his generous attitude towards harvest-purloining wildlife, but it’s consistent with his approach of putting something back.

Find out about elderberry, a native fruit bush.

American Persimmon

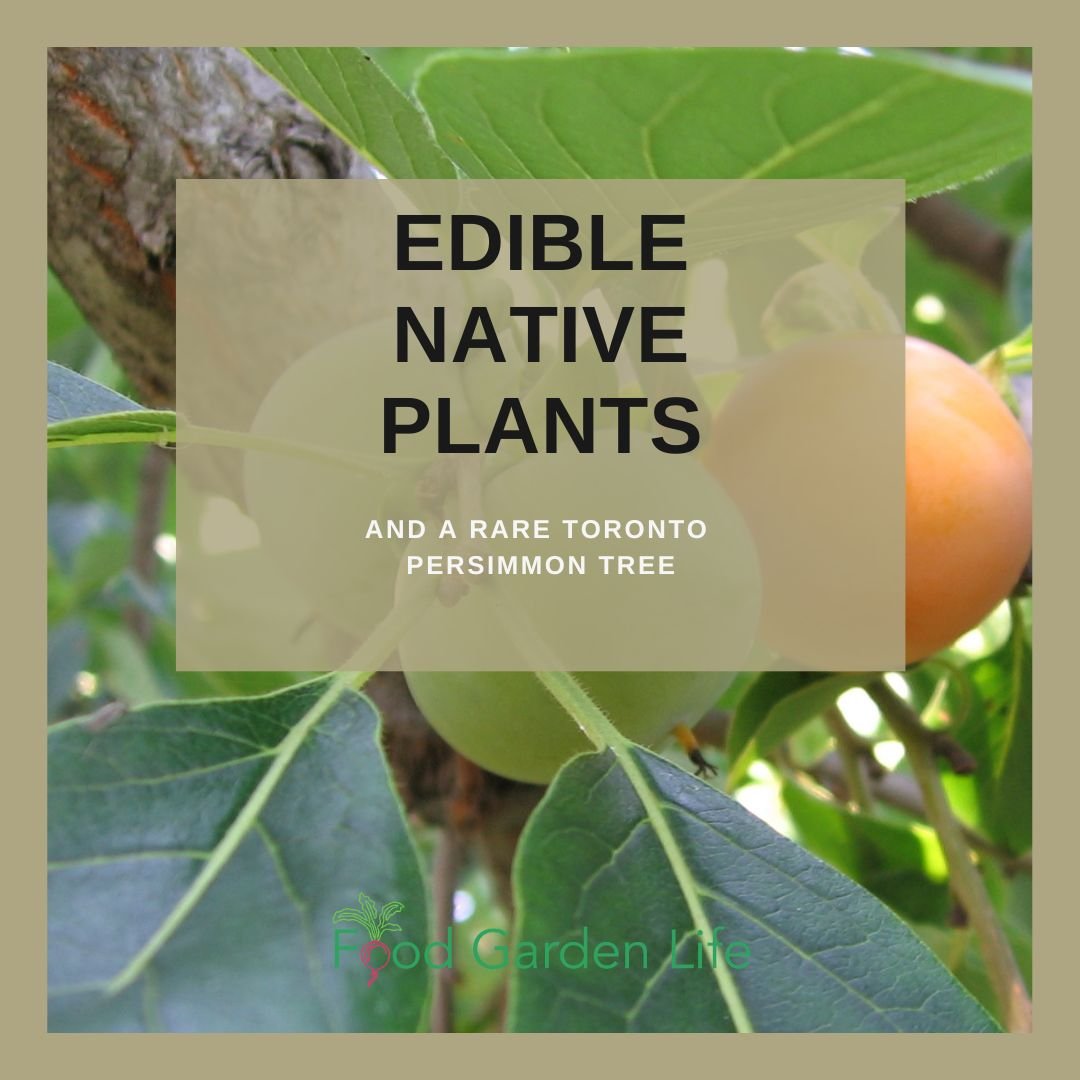

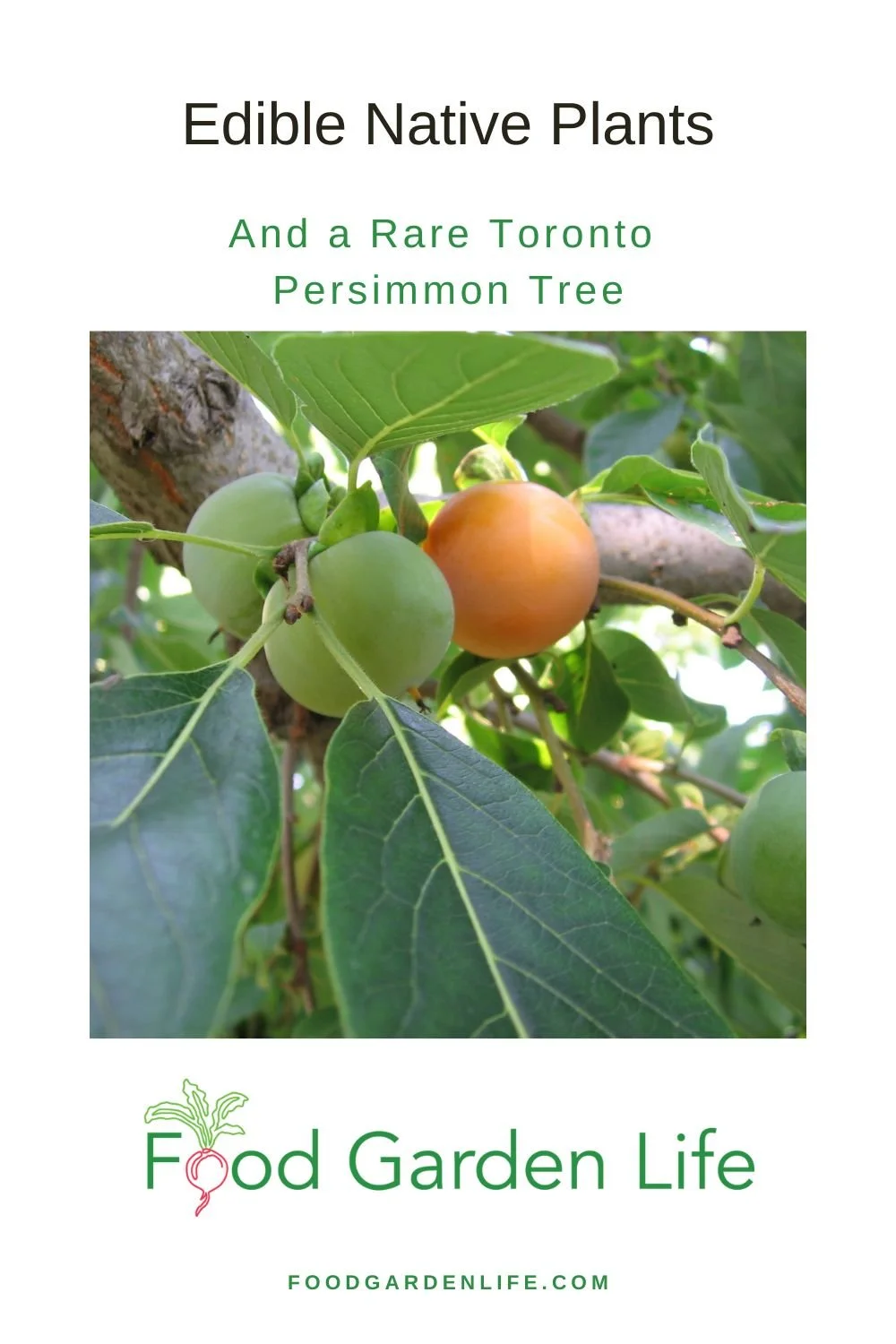

In the shadow of an American persimmon in Toronto. Grow persimmon in the warmer parts of Ontario.

Sitting under the American persimmon tree and looking up, I’m dismayed to find that the fruits are still green. Atkinson cautions that the fruit are astringent and bitter when unripe, so I satisfy myself with snapping pictures.

He explains that although this is a native North American species, it doesn’t usually grow wild this far north. But it grows well under cultivation.

(I found ripe, orange American persimmons a week later at Grimo Nut Nursery in Niagara, where the more temperate climate aids in ripening fruit earlier than in Toronto. They are sweet and velvety on the tongue; I’m delighted that the young persimmon tree I’ve been nurturing in my garden will have been worth the effort when it starts to fruit. And the fruit-laden trees are beautiful.)

Pawpaw

Atkinson's Toronto backyard, where he grows pawpaw trees and other native fruit trees.

Pointing to clusters of mango-like fruit, Atkinson says, “The fragrance of the pawpaw when ripe is aromatic.” He finds that the texture is like custard.

Each fruit usually contains four to eight seeds. “Like a watermelon, spit out the seeds,” Atkinson adds.

Don’t wait too long to pick it. “If it’s starting to turn brown, give it to the squirrels or raccoons,” he advises.

Pawpaws can be found growing wild on the north shore of Lake Erie into the Niagara region. Like the American persimmon, you’re not likely to find wild ones here in Toronto, but they do grow well here when planted. The large, lush leaves add a tropical feel to the garden.

Serviceberry

Serviceberry is a native edible plant well suited to growing in the city.

When it comes to native edible plants, Atkinson believes that one of the best to grow in the city is the serviceberry.

“There’s a whole bunch of them,” he explains, listing the related members of the serviceberry (Amelanchier) clan. They all have in common an edible fruit similar in size to a blueberry.

Palatability varies by species and variety. The saskatoon berry, which is also grown commercially, has consistently good fruit quality, according to Atkinson.

Serviceberry is widely planted in Toronto parks and is common in the nursery trade. They can be grown as a small tree or a bush.

In my own garden, I end up sharing my serviceberry harvest with robins if I don’t pick them quickly enough. Atkinson says that cedar waxwings like them, too.

Aside from the fruit, the serviceberry leaves turn a vibrant orange-red in the fall and the bark, smooth and grey, is showy, too.

Here’s a member of the serviceberry family that’s grown as a commercial crop: Guide to Growing Saskatoon Berries: Planting, Pruning, Care

American Hazelnut

American hazelnut is a native nut bush. It’s related to the European hazelnuts sold in grocery stores, but the nuts are smaller.

Hazelnuts send out attractive catkins in late winter, before any leaves are out.

Crabapple

“They’re a delight to look at,” agrees Atkinson as we change gears and talk about the sweet crab, a wild crabapple. “It puts on a really good show of flowers,” he says as he describes a blush of pink on white flowers in the spring, adding, “It’s as good as a flowering dogwood but in a different sort of way.” The fruit is very waxy, and very attractive, having a greenish yellow colour.

“Squirrels don’t touch it,” he exclaims. He likes the fall leaf colours, which range from yellow to burnt orange.

On the culinary side, he says the sweet crab fruit is sour, but a perfect accompaniment when roasted with a rich meat such as pork, where the tartness of the fruit cuts the richness of the meat.

Black Walnut

Atkinson speaks warmly of towering black walnut trees and of the beautiful dark wood they yield. He notes how common they are in the Niagara peninsula: “They’re almost like weeds.”

I agree with the weedy bit: My neighbour’s black walnut stops me from growing anything in the tomato family at the back of my yard. Despite its hostile actions towards my tomatoes, I have grown fond of sitting under that tree, never really considering why. “The shade under a walnut is really quite lovely,” he says, describing dappled light that results from the long leaf stalks adorned with small leaflets.

He discourages me from promoting the black walnut for edible uses because the nut meat is very difficult to extract: the shells are rock hard, requiring a hammer to crack. And the meat doesn’t come out easily like an English walnut, but has to be picked out. But by this point I’ve already decided to write about edible native plants because of their ornamental appeal.

Read about wicking beds, a way to deal with black walnut toxicity, a.k.a. juglone.

Growing Native Fruit in Urban Areas

I thank Atkinson for the tour and email correspondence. A couple of weeks later, Atkinson emails me a photo of a broken pawpaw branch. He writes: “Steve, here is what befalls a pawpaw when in an urban setting, and there are hungry raccoons about. I do not begrudge my masked friends at all for doing what inevitably they will do when after pawpaws.”

FAQ American Persimmon

Can persimmon grow in Ontario? Can you grow persimmons in Canada?

American persimmon is reported to be hardy into Canadian hardiness zone 4, though a long growing season with summer heat is needed for fruit ripening. Best in zones zones 5b-8.

Remember: Zones are only a guideline. Sometimes you can cheat if you have a warm microclimate.

Can I grow a persimmon tree from seed?

If you grow American persimmon from seed, the main thing to remember is that they are “dioecious.” This just means that a plant can be male or female. If you grow a seed and get a male plant, you won’t get fruit from it.

Many commercial varieties produce fruit without a male.

Interested in Forest Gardens?

Here are interviews with forest garden experts.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More Information on Growing Fruit

Articles and Interviews about Growing Fruit

Courses on Fruit for Edible Landscapes and Home Gardens

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

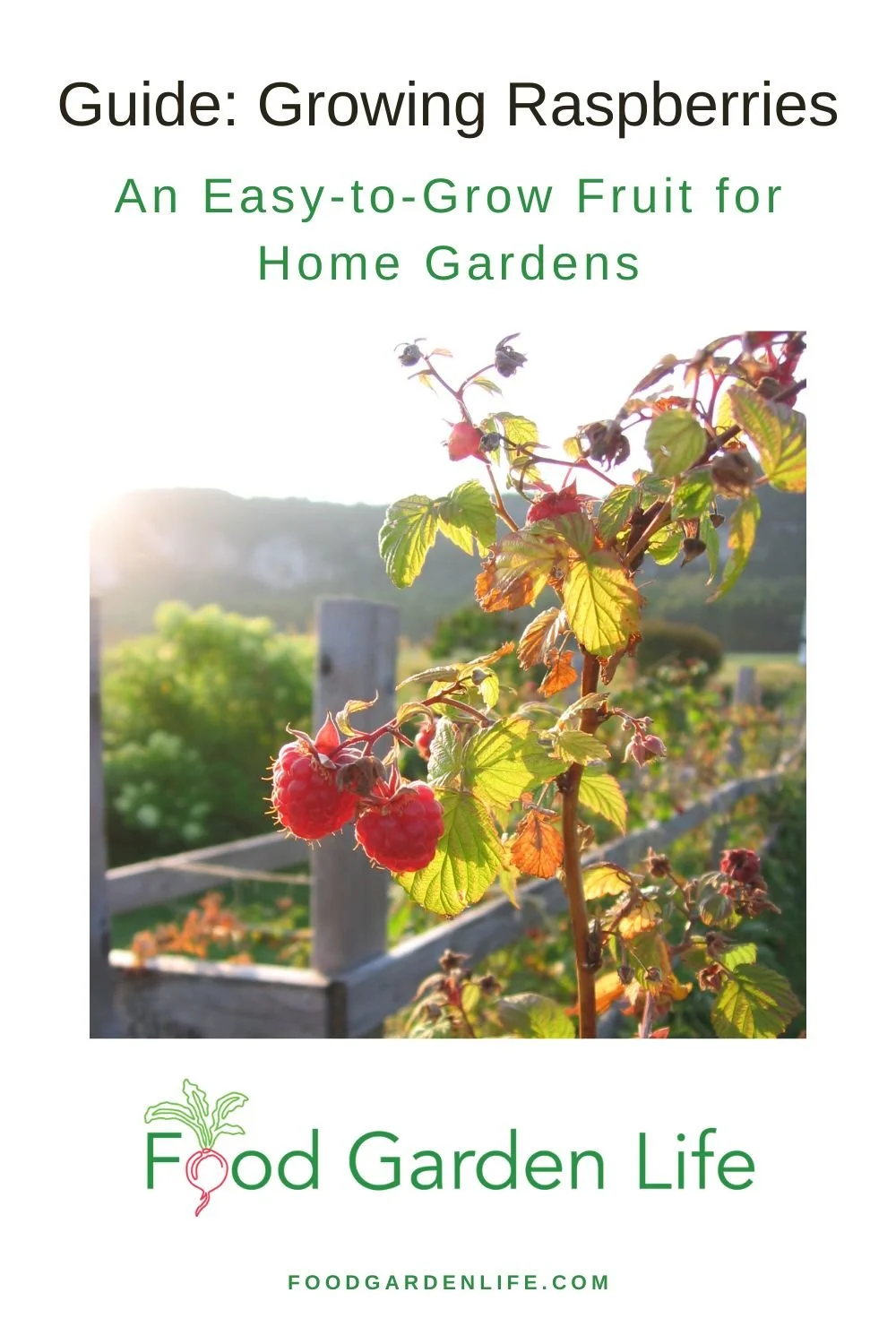

Guide: Growing Raspberries (high yield, NO fuss fruit)

This article explains how to plant and care for raspberries in a home garden.

How to Grow Raspberry Plants

At the back of my aunt and uncle's house was a berm made of heavy yellow sticky clay. It was the soil excavated from an addition to their house. The contractor just dumped soil and rubble at the back of their yard.

And it became their raspberry patch.

Raspberries are well suited to the home garden because they’ll thrive in imperfect conditions like that hard-packed berm.

A home gardener can take a very systematic approach to raspberry care…or a hands off approach. Both work with raspberries. (Though by investing some time, you increase the harvest.)

If you want to find out how to grow raspberries, get ideas for using them in the landscape, and find out top tips for raspberry care, keep reading. This post tells you how.

Primer for Growing Raspberries

Let’s start with some raspberry basics.

How Raspberries Grow

A raspberry plant has perennial roots, but the canes live for only two years.

Raspberry bushes have perennial roots (meaning it lives for many years) but the tops—called the “canes”—live for only two seasons.

First-year canes are called “primocanes.” They start out green and tender, and get brown and woody as the season progresses.

Second-year canes are called “floricanes.” Floricanes flower and produce fruit, and then die at the end of the season.

Raspberries that produce fruit on the floricanes are called summer-bearing raspberries or summer-fruiting raspberries.

But some varieties of red and yellow raspberries grow a later crop of fruit on primocanes. These are called everbearing raspberries, fall-bearing raspberries, autumn-fruiting raspberries, or primocane raspberries.

Raspberry Fruiting

Raspberries are late to flower, so flowers are not likely to be hit by late frosts.

You don’t need multiple varieties to get fruit because raspberries are self-fertile. You will get fruit even if you have only one plant.

Here’s when raspberry fruit ripens:

Fruit on floricane-fruiting varieties ripens early summer through to midsummer.

Fruit on fall-bearing varieties ripens mid to late summer. If winter is slow to arrive, you can harvest raspberries until there’s a heavy frost.

Raspberry Growth by Fruit Colour

Yellow raspberries are the same species are red raspberries.

There are red, yellow, black, and purple raspberries. The red raspberries and yellow raspberries are the same species. Black raspberries are a different species. And purple raspberries are a hybrid of red and black.

Red and Yellow Raspberries

Red raspberry and yellow raspberry plants send up new canes from the base of existing canes. New canes also grow from the roots. That means that they don’t remain in a clump, and plants spread out in all directions.

Black and Purple Raspberries

These grow in a tidy clump, with new shoots growing from the base of the clump.

Where to Plant Raspberries

Black raspberries.

If you want to grow raspberries by the book, look for full sun and a rich, well-drained soil.

But in a home garden setting, we don’t always have the ideal conditions that a market gardener might have.

You don’t have to give raspberries the prime real estate.

They grow in a wide range of soils. Very sandy or very heavy clay are the least ideal—both situations can be helped by adding lots of organic matter. The ideal pH is around 6, though they can do fine on many soils.

They don’t do well in soil that’s continually wet. So avoid wet locations. Or, if you only have a wet location, consider raised beds.

Raspberries are affected by a disease called verticillium wilt. There are a few common plants that we grow in home vegetable gardens that also get verticilium wilt: the nightshades (tomato, eggplant, pepper, potato) and strawberries. If you've been growing these and you've had wilting and dieback, this is a red flag. Put your raspberries in another part of the yard.

Planting Raspberries

Purple raspberries.

A raspberry patch can last many years. So set it up right.

Your first step is to get the soil in good shape by adding lots of compost.

Next, make sure there are no perennial weeds.

Raspberry Spacing

How you space raspberry plants depends on how you’re fitting them into your yard. However you do it, though, your red and yellow raspberries will fill in the spaces soon enough.

Rows Make Picking Easier

Raspberries are easier to pick when you grow them in rows. If they’re in a patch, you have to blaze a trail for picking…and that might mean scratched arms!

I like rows that are at least 60 cm (2’) wide. Wider than that and they’re more difficult to pick. Leave 60-90 cm (2-3’) between plants. Because black and purple raspberries have long, arching canes, you can space them a bit farther apart.

Raspberry Hedge

Your neighbours might take issue with me for mentioning this…but what about a raspberry hedge as a way to separate yards? Because they sucker, a raspberry hedge creeps outward—so be prepared to rein it in.

Raspberries in the Landscape

Beyond rows or hedges, wherever you plant them, keep in mind that raspberries spread.

This is a plant that’s perfect in a spot with natural boundaries—like a space framed by a house and a patio.

In the wild, raspberries often grow in partial shade, at the forest edge. Think of this if you’re creating a layered landscape or a food forest.

I’ve seen commercial raspberry production in high tunnels, both in the ground and in pots. This is more work than most home gardeners want, but it gives the gardener more control of conditions, meaning the chance to boost yield. It also extends the fall harvest window.

Raspberry Care

Weeding

In an established raspberry patch it’s difficult to remove perennial weeds like thistle or bindweed. So don’t let them get established!

Raspberries have shallow roots, so don’t deeply cultivate the patch. You can scuff the surface or spot-dig bigger weeds.

Even better, minimize weeding by mulching your raspberry patch. This also helps to hold in moisture.

Trellising

Trellising raspberry plants with a T at either end of the row, and wires strung in between.

A simple way to support raspberry canes in rows is to have a horizontal wire running the length of the row on either side of it. To do this, install posts at the end of the row and put pieces of wood across the posts, so they’re T-shaped. Then run wires from one T to the other. The wire can be 1 – 1.5 metres off the ground—depending on how tall your canes are (which depends on the variety and the growing conditions.)

In short, you’re just getting canes to grow between horizontal wires, which prevent them from leaning too far away from the row.

A variation for those growing a skinny row of raspberries is to have a single wire down the centre, and then tie each cane to it.

Note: Fall-bearing types can get tall and top heavy when laden with fruit. If so, trellising help keep canes upright.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Pruning Raspberries

If you let every cane grow, you’ll have smaller fruit. If you thin out canes, those remaining give more—and bigger—fruit.

If you’re managing your raspberries more intensively, you might opt to prune twice a year, with summer pruning and dormant pruning. You’ll still get raspberries if you don’t prune, but you can optimize production (and have a nicer looking patch) with regular pruning.

Summer Pruning

Prune out weak primocanes. Thicker, more vigorous canes give more fruit.

I aim for 30 cm (12”) between primocanes, bearing in mind that in a wide row there can be more than 1 cane in a 30 cm (12”) span.

Pinch tips of new black and purple raspberry canes mid-summer to encourage side branching.

After floricanes finish fruiting, cut them out (you can also just wait to do this later, while the plant is dormant).

Dormant Pruning

These floricanes will be pruned out at the end of the growing season.

I prune in the fall. In colder climates, prune late winter or early spring pruning so winter dieback can be removed with pruning.

Prune red (and yellow) raspberries back to 1.2-1.5 metres (4-5’) high before growth begins. This encourages more side shoots…meaning more fruit.

Cut back side branches on black and purple raspberries by half before growth begins in the spring.

Here’s an Idea: If you have fall-bearing raspberries and want only the fall crop, cut all of the canes to the ground in the spring before growth begins.

Water

Water raspberries during dry conditions to prevent dry, seedy fruit.

Raspberry Varieties

Here are things to think about as you choose raspberry varieties:

Hardiness

Summer or fall bearing

Taste

For summer varieties, there are early-, mid-, and late-season varieties

When it comes to varieties, it’s worth doing your homework to see which varieties are recommended for your area. Hardiness varies between varieties. Taste varies quite a bit too—so as you’re looking at zone ratings, see how the flavour is rated.

If you have a short growing season, there might not be enough time for fall-bearing raspberries to ripen. That’s because ripening stops and plants start to shut down with the first hard frost. To find out more about taste and what varieties do well in your area, ask other gardeners—or check in with a nearby pick-your-own farm.

In areas with winter thaws followed by extreme cold, where winter dieback is a concern, an early-fruiting primocane raspberry has the advantage of not relying on overwintering canes

Black raspberries not as cold hardy as red and yellow raspberries.

Challenges

Competition

My main competition for berries is my kids. But for many gardeners, it’s birds. Because canes are fairly low, netting, or growing in a net tunnel, are options.

Decline

A raspberry patch usually goes into decline after a few years. Start a new patch, on another piece of ground.

Raspberry Propagation

Use a spade to divide clumps in the fall, or in the spring before new growth begins. Spring and fall are also the time to dig up wayward suckers from red and yellow rapsberries.

Black and purple raspberries can also be propagated by tip layering. Here’s an explanation of tip layering for blackberries; it’s the same process for purple and black raspberries.

Buy Raspberry Canes

Many garden centres sell potted raspberry plants. The advantage to container-grown plants is that the planting window is much wider. But they cost much more than bare-root plants.

Dormant bare root plants, with roots washed of soil, are shipped in late winter and spring. These are available from many online nurseries—and the price per plant is considerably cheaper than potted plants.

FAQ – Grow Raspberries

Pin this post!

Do raspberries grow in shade?

They tolerate partial shade well, though the yield is less than in full sun. My productive black raspberry patch gets only a half day of sun.

Does frost affect raspberry flowers?

It can, but because the flowers are late to open, it’s rarely a problem.

I want to renew my raspberry patch with new plants. Can I put it where my current patch is?

It’s better to choose a fresh piece of ground, if that’s an option. That’s because raspberries planted where there were recently raspberries growing might not do as well. If your old patch had disease, it can affect the new plants.

Why does my raspberry fruit crumble?

If the ripe berries crumbles when you pick them, the problem might be poor pollination. This can happen when the weather at the time of bloom is rainy or overcast.

Can raspberries grow in a pot?

Yes. Raspberries grow well in containers. As with any container-grown crop, success depends on providing a large enough container, and sufficient water and feed.

More on Raspberry Plants

And here’s more on how to tip-layer blackberries and black raspberries.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Fruit Crops

Articles: Grow Fruit

Visit the Grow Fruit home page for more articles about growing fruit.

Here are a few popular articles:

Courses: Grow Fruit

Here are self-paced online courses to help you grow fruit in your home garden.

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

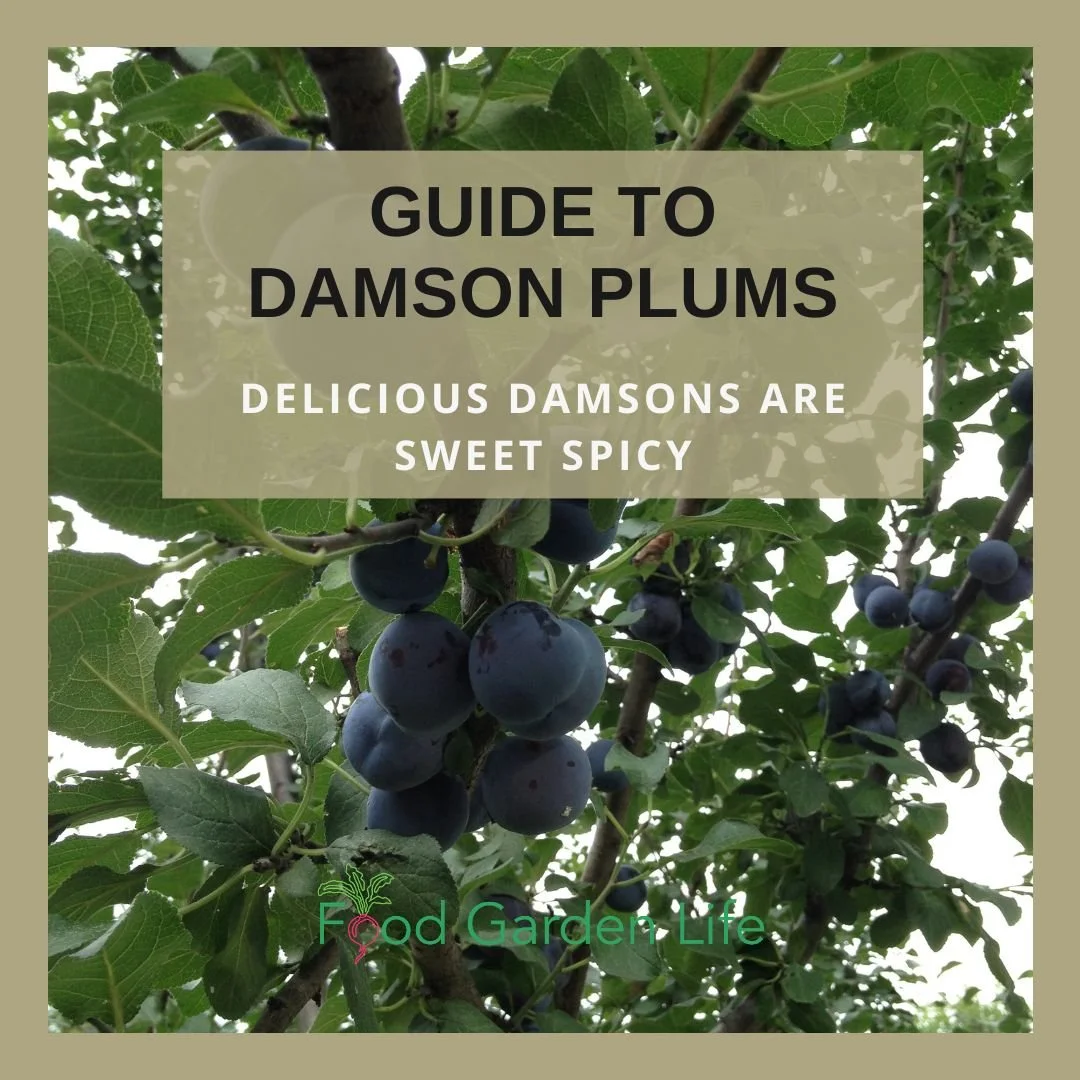

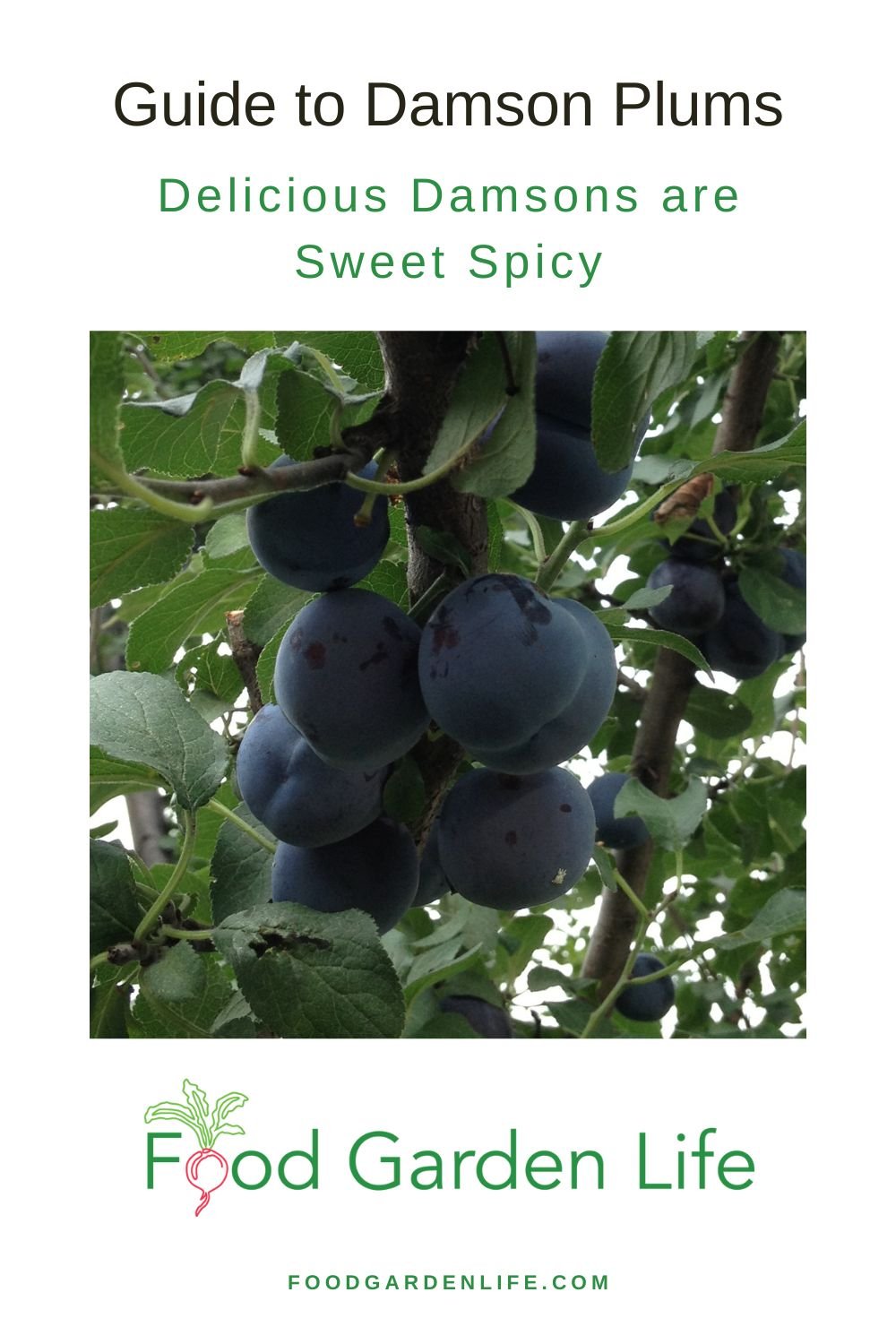

Damson Plums: This Forgotten Fruit Combines Dry, Sweet, Spicy, and Bitter (and it’s a perfect home-garden crop)

Find out how to grow this forgotten fruit that has a rich, complex flavour. It’s a gem in the kitchen, and easy to grow in a home garden.

By Steven Biggs

Disappearing Damsons

I remember when Nana started to ration the jam. The damson jam.

She was running low on her homemade damson jam. And what was left was reserved for damson tarts—one of her specialties.

She couldn’t get damsons any more.

Why the fuss? Because damsons have a special flavour and make marvellous jam. They’re the ultimate plum for cooking, with a rich, complex flavour that combines sweet, spicy, slightly sour, and a touch of bitter.

I was just a kid at the time. Since then, I’ve rarely seen damson fruit or damson trees for sale. Too bad, because it’s a unique fruit that’s well worth a place in a home garden.

But they’re not completely forgotten.

When I drove through the Kamouraska region of Quebec, I took a detour especially to visit Maison de la Prune, a small damson orchard and museum in what was once a major damson production area. I came home with damson syrup, and sweet and savoury jellies.

Keep reading to find out more about this special plum, and how to successfully grow it.

Hear a Damson Expert Explain What’s Special About Damsons

What is a Damson Plum?

Damsons (Prunus insititia) are smaller and not as sweet as their cousin the European plum (Prunus domestica). (Quick plum primer…it’s a big family, including Japanese plums, P. salicina, North American plums, P. americana, and the cherry plum, P. cerasifera.)

A damson is a small, oval-shaped plum. The skin is often a deep blue-purple colour, with yellow flesh, although there are also yellow-skinned varieties. They’re a “clingstone” fruit, meaning that the flesh, which is quite firm, is attached to the stone. Like many fruit in the plum family, the fruit has a waxy “bloom” on it, giving fresh damsons a silvery hue.

Damsons are self-fertile—meaning only one tree is needed to get fruit. They bloom in early spring, with fruit starting to ripen in late summer.

How are Damsons Different From Other Plums?

The damson is smaller than the European plum. These damsons will ripen to a purple colour.

When it comes to the plant itself, the trees have a more compact growth than other domestic plums, developing a gnarled shapes as they get older.

The fruit is smaller too, with more stone and less fruit than other domestic plums—up to one third stone. The fruit is also drier than European plums and Japanese plums.

While damsons are sweet, they’re also slightly astringent, giving them a complex flavour and making them superb for cooking. (Perhaps less attractive for fresh eating, though I love them.)

Along with the astringency comes a spiciness and sweetness that sets them apart from domestic plums.

What is a Bullace?

It’s worth noting a couple of other relatives that are sometimes included when talking about damsons. Along with damsons, Prunus insititia includes bullaces, and St. Julian plums.

St. Julian plum is mostly grown as a rootstock for grafting damsons

The round bullace fruit is smaller than damsons, ripening later, and has a less complex flavour

The bullace is different from the sloe (Prunus spinosa) which is bushier. If the sloe is new to you, look up sloe gin. (I know of sloes because my dad had a bottle of sloe gin when I was growing up.)

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

How to Grow Damsons

Planting Damsons

The first thing to know is that damsons are self-fertile. This means that you can plant one damson tree and get fruit.

Like other fruit that flower early—while there’s still a risk of frost—choose a location where there’s less chance of flowers getting hit by frost. This means:

Avoid low-lying pockets that get heavy frost when other parts of your garden don’t

If you’re in an area with late spring frosts, a north-west-facing slope can be safer than a south-facing slope (it might seem counter-intuitive…but they’ll bloom earlier on a south-facing slope, meaning more chance of frost damage)

Hear a fruit expert talk about site selection in cold climates.

Where to Plant a Damson Tree

Full sun is best for damsons. They tolerate semi-shade if that’s all you have.

Damsons grow in a wide range of soil types. Avoid acidic soils and soils that dry quickly—meaning sandy soils.

Stake newly planted trees for a year to prevent shifting.

Spacing When Planting Damsons

Damsons are a relatively small tree.

Here are a couple of considerations when deciding on spacing between damson trees:

With grafted trees, the tree size and optimal spacing depends on the rootstock

Space between trees allows air flow, which helps reduce disease pressure

In a home garden setting, there are often competing needs for a small space. In that case, you might want to be creative with spacing. For example:

Plant more than one damson tree in a hole – a clump of damsons

How to Care for Damson Plums

Below is more information about how to care for damsons. But to sum it up quickly in case you’re already a fruit grower: Treat damsons as you would other plums.

How to Prune Damson Plum Trees

Damson fruit in mid summer. They have a golden-yellow flesh when ripe.

If you’re growing damsons in a hedge, you might take a hands-off approach to pruning.

When you’re growing damsons as separate trees, use pruning to shape the tree into a framework of branches that gives good strength, and allows air circulation and ease of picking.

A tree from a nursery might already have a framework developed. If it’s a young tree, you can develop the framework of branches yourself. Damsons can be formed into central-leader style trees, vase-shaped trees, or into a bush. For a bush, picture a short trunk, with branches coming out above that.

Pruning fruit trees is an entire article unto itself, but here are top tips:

Avoid narrow, v-shaped angles

Don’t make sloppy cuts that leave a nub of branch beyond a bud

Remove crossing branches

Aim to keep the canopy of the tree open, to allow air movement

Like other stone fruit, damsons don’t respond well to attempts to train them into cordons.

Prune in late winter.

Protecting Damson Blossoms from Frost

With a well-chosen site you’re less likely to have frost damage in the spring…but if there is a late frost, and if your damson tree is small enough, a simple cover might protect the blossoms.

Drape the plant with burlap or horticultural fleece. (I’ve even covered tender plants with an old shower curtain!)

Damson Hardiness

Damsons are very cold hardy. There’s no question of hardiness here in my Toronto garden.

I’ve seen Canadian nurseries listing damson varieties hardy into Canadian Plant Hardiness Zone 3, and American nurseries suggesting USDA Zone 5. Here’s a list of nurseries that sell fruit trees.

Consider zones a general guide. Conditions within a zone can vary—and microclimates allow gardeners to push zone boundaries. There can be “frost pockets” in low-lying areas, and moderate areas near large bodies of water.

With grafted plants, hardiness depends on how hardy the top (scion) is—and how hardy the bottom (rootstock) is.

How to Propagate Damson Plums

Damson Seeds and Suckers

In times past, damsons were commercially propagated using seeds and suckers.

Seeds. When grown from seed, many damson varieties “come true,” meaning the new plant is like the parent. If you want to seed-grow damsons, first stratify the seed, and then sow in a pot or directly in the garden.

Suckers. Suckers are the shoots that come from the base of a mature plant, and already have roots. This is an easy way to get started if you know that the tree is not grafted. (If it’s a grafted tree, a sucker might actually be coming from the rootstock.)

Grafting Damsons

Most commercially produced damsons are propagated by grafting.

Under some conditions, damson trees can grow up to 6 metres (20’) tall. But if conditions are not as good—or if trees are grafted onto a rootstock that restricts growth—they’ll be smaller.

This means that it’s good to know how rootstock can affect damson tree size.

Here are common damson rootstock:

Large. Myrobalan B, Brompton

Medium. St Julian A

Small. Pixy, VVA-1

Damson Harvest

Pick damsons as they develop colour and as the fruit becomes softer to the touch.

Damsons ripen in late summer and early fall.

When are Damson Plums Ripe?

Pick as the damsons become soft to the touch. (You can pick them earlier if making gin.)

Why Damsons Sometimes Fruit Every Second Year

It’s common to have what’s called “alternate bearing,” meaning a large crop one year, and then very little—or nothing—the next. This happens because when a fruit tree carries a heavy crop, energy goes to the ripening of that crop—and flower buds are not formed for the next year.

You can prevent alternate bearing by thinning fruit.

Damson Pests and Diseases

Black knot disease.

Mice and rabbits often gnaw on fruit tree bark over the winter. While damson trees are young, use a spiral tree guard around the trunk for the first few winters to protect the bark from rodents.

Black knot is a fungal disease that affects many plants in the plum family, including damsons. Some damson varieties have more black-knot resistance than others. You can recognize black knot by the black, woody growth encircling a branch. (My kids called it poo on a stick when they were little.)

If you see black knot, prune the affected branch back at least 20 cm (8”) below the knot. Don’t leave the pruned-off branch near your damson trees because the knot provides inoculum for more infection.

Damson Recipes

I started off by telling you about my Nana’s damson plum jam. It was so delicious because of the balance that the damsons give, with the combination of fruitiness, sweetness, spiciness, tartness, and a little bit of astringency. Damsons are excellent for jams, fruit butters, and for making fruit cheese because they contain a lot of pectin.

Because they’re “clingstone,” the fruit is usually separated from the stone after cooking.

There are many more ways to use damsons. You’re more likely to come across these in the UK, where there’s a longer tradition of cooking with them.

Damson chutney

Pickled whole damsons

Damson vinegar

Damson gin

Use them where you would use other tart fruits. And think of using them with savoury dishes—not just sweet. That’s because the combined tartness and astringency work well with rich dishes.

(And if you don’t have the time or inclination to spend a lot of time in the kitchen, stewed damsons are a true delight. When I lived in the UK there were damsons in a nearby hedgerow. I’d stew them, cooking with a bit of water and sugar until soft enough to the damson stones. Then I’d eat them with clotted cream.)

For more recipe ideas, I recommend the book Damsons: An Ancient Fruit in the Modern Kitchen.

Where to Buy a Damson Plum Tree

While you might not see damsons at garden centres, specialist fruit tree nurseries often carry them. If ordering online, look for bare-root trees so shipping costs are lower.

Here’s a list of fruit tree nurseries.

The choice of damson varieties in North America tends to be limited. I’ve most often seen damsons sold as Blue Damson.

(You sometimes see them sold as “Damas Bleu,” as there’s also a long history of damson production in Quebec. If you want to delve into that, here’s a fun book: Les Fruits du Québec: Histoire et traditions des douceurs de la table, by Paul-Louis Martin, who is the proprietor of Maison de la Prune that I mentioned earlier.)

In the UK there is a wider selection of damson varieties. I have a 1926 text that lists Blue Prolific, Bradley’s King, Farleigh Prolific, Quetsche, Rivers’ Early, Shropshire Prune, Merryweather. If you search UK nurseries, you’ll see many of these are still available.

Using Damson Trees in Garden Design

Damsons are good choice for a home garden because they are self-fertile. That means that in a small space, you only need one tree to get fruit.

Here are ideas for using damson trees in garden design.

Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

Damsons work well in edible landscapes with a mixed planting of edibles, and in a food-forest setting. Like many fruit trees, they do best in full sun, but tolerate the sort of partial shade that you can get in an urban edible landscape or on the periphery of a food forest.

Home Orchard or Stand-Alone Specimens

A more traditional planting gives each tree enough space to fully develop. The amount of space needed for well developed, well-spaced damson trees depends on the rootstock.

Hedges and Hedgerows

In my own garden, my damsons are part of a fruiting hedge. There are damson and other plum trees in a long row, underplanted with currants and gooseberries. At ground level are strawberries. It’s still rather neat and tidy, but damsons could work well in a less formal hedgerow or windbreak too, mixed with other small fruit.

Here’s a chat with a small fruit specialist to get ideas for less common fruit for a hedge.

FAQ: Damson Plums

How long should I stake a damson tree?

Remove stakes after the damson tree is established and has rooted into the surrounding soil, usually after one season.

Why are so many fruit dropping off in early summer?

There’s a natural fruit drop in early summer. As long as there are lots of fruit remaining on the tree, everything is probably OK.

Do damson trees fruit every year?

Not always. If there’s a heavy crop one year, there might not be a crop the following year. This is called alternate bearing. You can thin fruit to reduce alternate bearing.

What is the botanical name for damsons? Why am I seeing two different botanical names for damsons?

Good question. You might find damsons as Prunus insititia or as Prunus domestica subsp. insititia. That’s because plant taxonomists sometimes rename things.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Fruit Crops

Articles: Grow Fruit

Visit the Grow Fruit home page for more articles about growing fruit.

Here are a few popular articles:

Courses: Grow Fruit

Here are self-paced online courses to help you grow fruit in your home garden.

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Nursery List: Fruiting Shrubs, Unusual Fruit, and Hardy Fruit Trees

Where to find fruit trees for sale.

By Steven Biggs

Buying Fruit Trees, Fruiting Shrubs, and Berry Bushes

I get a lot of messages from people wondering where to buy fruiting plants. So I hope this list helps you find a nursery with the fruit trees you’re looking for.

This list focuses on nurseries, garden centres, and fruit-growing specialists in Canada and the northern USA.

It’s a work in progress. If there’s a nursery you recommend, please e-mail me to let me know.

Before you browse nurseries, get started with Tips When Shopping, below.

Tips When Plant Shopping

Here are tips to keep in mind as you get ready to order trees and shrubs.

Delivery vs. Pick-Up

It’s expensive to ship trees and shrubs! They’re big. And if there’s soil—they’re heavy too.

Delivery costs depend on the distance, the size of the plant, and whether it’s in a pot with soil, or is “bare root.”

(Bare root means it’s dormant, and there’s no soil.)

If picking up your fruit plants is an option, you can usually save quite a bit of money.

Ordering and Shipping Fruit Trees and shrubs

Shipping usually begins in spring, when there’s no further risk to the plants from cold temperatures.

The first to ship are “bare root” plants—dormant shrubs and trees with no soil. (Roots are wrapped in something damp to prevent them from drying out.)

Cross-Border Shipments

Some sellers don’t ship out of country. That’s because it usually involves “phytosanitary” inspections and paperwork.

Or, there might be restrictions on shipping some types of fruit to some regions (to avoid the spread of pests or diseases.)

If you find an out-of-country vendor who ships to your country, ask about the cost of phytosanitary certificates—as well as the delay that inspections can cause for your shipment.

When You Receive Your Order

Bare-root Plants. Keep them somewhere cool and dark until you’re ready to plant them, so that they remain dormant. Plant as soon as possible. Make sure the roots stay moist.

Potted Plants. There’s less of a rush planting potted plants than there is with bare-root plants. Keep plants well-watered until they’re planted.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Canada Nurseries

Bambooplants.ca

Ontario

Great selection of minor and unusual fruit plants.

Boughen Nurseries

Nipawin, Saskatchewan

Boughen sells fruit trees and berries for cold climates. This is where I found my favourite culinary crabapple, ‘Dolgo.’ They also have Nanking cherry, which, despite being easy to grow, can be difficult to find in many parts of Canada.

Corn Hill Nursery

King’s Country, New Brunswick

Owner Bob Osborne is a CBC radio columnist, and the author of the book Hardy Apples: Growing Apples in Cold Climates.

Hear Bob tell us about hardy apples on The Food Garden Life Show.

DNA Gardens

Elnora, Alberta

Specializing in hardy fruit trees.

Exotic Fruit Nursery

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Hardy fruit, exotic fruit, and nuts.

Fruit Trees and More

North Saanich, British Columbia

A nursery and experimental orchard. Well worth a visit if you’re in the area—but they do mail-order too. Lots of less common fruit such as medlar and Asian pear. (And olives, citrus, and figs!)

Grimo Nut Nursery

Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario

A specialty nut nursery that also has uncommon fruit such as American persimmon and a number of mulberries.

Linda Grimo shares tips on how they prune mulberries in this guide to growing mulberries.

Hardy Fruit Tree Nursery

Rawdon, Quebec

Some good articles about growing fruit trees on the website. Grafting onto full-sized rootstock.

Nutcracker Nursery

Maskinongé, Quebec

I’ve ordered plums and damsons here and was pleased with the quality of the plants.

Pépeinière Ancestrale

St-Julien, Quebec

This is where I got my first cherry-plum bushes! Fruit trees and nut trees.

Prairie Hardy Nursery

Two Hills, Alberta

Recommended to me by my horticultural colleague in Alberta Donna Balzer.

Production Lareault inc.

Lavaltrie, Quebec

Berries and small fruit. (Also asparagus, rhubarb, and kiwi.)

Rhora's Nut Farm and Nursery

Wainfleet, Ontario

Specializing in nut trees, with some minor fruit too.

Riverbend Orchards

Portage la Prairie, Manitoba

Cold-hardy fruit bushes, including haskaps, currants, and cherries.

Silvercreek Nursery

Wellesley, Ontario

Some of my apple trees are from Silvercreek—and I took a fantastic grafting workshop there.

T&T Seeds

Headingley, Manitoba

Seeds, accessories, and fruit plants by mail order. Also a garden centre if you’re in the area.

TreeMobile

Toronto, Ontario

A not-for-profit organization supplying fruit trees and supplies to gardeners.

Hear our chat with TreeMobile founder Virginie Gysel.

Whiffletree Farm and Nursery

Elora, Ontario

Trees, small fruit, and orchard supplies.

Willow Creek Permaculture

Dutton, Ontario

Fruit and nut trees.

USA Nurseries

Pin this post!

Edible Landscaping

Afton, Virginia

Fruit trees, fruit bushes, berries, and exotics like citrus.

Honeyberry USA

Bagley, Minnesta

Cold-hardy fruit bushes including honeyberry, a.k.a. haskap.

Off the Beaten Path

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lots of figs, as well as other unusual fruit.

Hear the owner, Bill Lauris, talk about figs in this podcast episode.

One Green World

Portland, Oregon

We chatted with Sam Hubert from One Green World on the podcast to find out all about hardy citrus. They carry lots of other fruit trees, fruit bushes, and berries too.

Raintree Nursery

Morton, Washington

A diverse collections of edible plants including nut trees and nut bushes.

Trade Winds Fruit

Seeds for rare and unusual fruit.

More Sources for Plants

Here’s a Fig Nursery List to help you find fig trees for sale.

More on Growing Fruit

Head to the Growing Fruit Home Page for articles, interviews, and guides on how to grow fruit.

Planning a Kitchen Garden that Awes (in Purple!)

Make a kitchen garden with a mix of your favourite crops.

By Steven Biggs

Grazing the Kitchen Garden

How to make a kitchen garden you love.

My family doesn’t think it’s unusual to hear the back door open and close as I cook supper.

They see me come in with a fistful of herbs. Or a colander with vegetables, fresh fruit, and edible flowers.

I think of it as grazing: Picking what’s ready from my kitchen garden: Small portions of a wide variety of ingredients for our meal.

What’s ready in the garden inspires what I make for supper.

Along with a varied, continuous harvest, there’s something else I think about when planning a kitchen garden: Creativity. A great kitchen garden touches the senses. Taste is obvious, smell too. But there’s also touch, sound, and sight.

If you’re looking for great kitchen gardening ideas, keep reading. I have ideas for you about how to make a kitchen garden you love.

Planning a Kitchen Garden – and Having Fun Doing it

The planning stage of gardening can be intimidating. There’s crop spacing, crop timing, succession crops, crop rotation, and more…

So before I throw out ideas for you, here’s my top advice: Have fun. The compost pile takes care of things that don’t go as planned.

Next suggestion: Be playful with style and design because it’s a personal thing. A kitchen garden plan is a personal creation. (And the fun part is that every year you can create something new!)

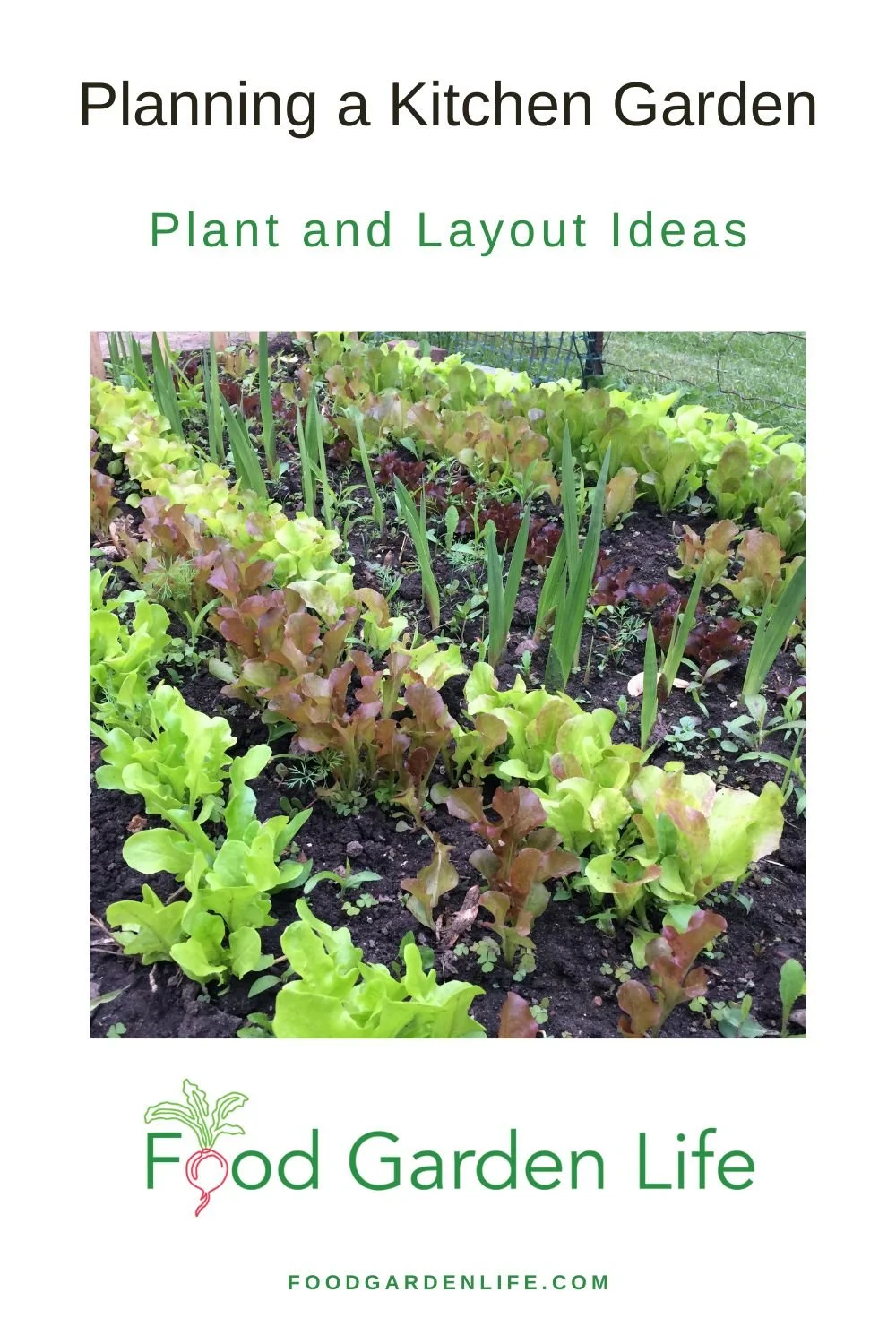

What is a Kitchen Garden?

How is a kitchen garden different from a vegetable garden? It depends who you ask.

When I think of a kitchen garden I think of a mix of edible plants including herbs, vegetables, fruit, edible flowers, and flowers for cutting. That sets it apart from a traditional vegetable garden geared towards large harvests for canning, freezing, and storing.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Creative Kitchen Gardens

More than a Vegetable Garden

It was late fall and this kitchen garden was getting tired, but the playful design and colour theme still shone through.

However you define a kitchen garden, don’t just make it functional. Make it something that gives you a jolt of delight when you see it.

For example, this fall I took a trip to the William Dam Seeds trial garden. It was late in the season and things were past their prime. But I was still riveted by what remained of their playful purple-themed garden. It was a mix of flowers, veg, and herbs.

Purple kale, purple basil, purple cauliflower, purple beans…and more.

There were lots of edibles. There was also a hefty dose of flowers. And the garden gave a wallop of colour. It had height. It was fragrant. And it was a playful pinwheel design.

My daughter Emma and I were intrigued by the use of patterns and shapes in the Food Garden at the Montreal Botanical Gardens.

I’m not suggesting a purple-themed garden for everyone. I mention the purple-themed garden to help you think about making your kitchen garden special for you.

So think about:

Colourful crops

Texture

Shapes and patterns

Plant-themes (e.g. lots of lettuces!)

Here’s a fun idea…a dragon-themed garden for kids (seriously! See below.)

Creativity is what makes kitchen gardens shine.

Don’t be afraid to play with texture in the kitchen garden! Here’s an X of celery between cabbage plants at the Food Garden at the Montreal Botanical Gardens.

Purple-Themed Fun

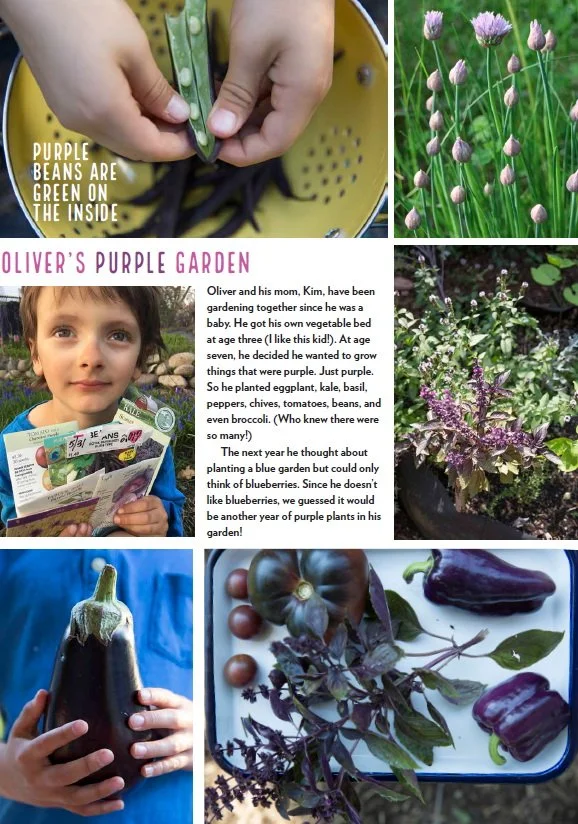

The purple trial garden reminded me of the purple-themed kids garden my daughter Emma included in her book Gardening with Emma.

From the book Gardening with Emma.

The gardener, Oliver, was 7 years old. He told his parents he wanted a purple-themed garden.

When Emma got in touch with him for the book, Oliver was growing these purple crops:

Eggplant

Kale

Basil

Broccoli

Peppers

Chives

Tomatoes

Beans

More Colourful Edibles

I was thinking about Oliver’s purple kitchen garden, and jotted down purple crops in my garden that we can add to his list of purple crops:

Lavender

Purple peas

Purple mustard

Purple bok choy

Bronze fennel (OK, looks purple to me!)

Purple-leafed elderberry

Purple asparagus

Purple might or might not be your jam. If it’s not, think about what delights you.

Where to Put a Kitchen Garden

Every yard is different. Every gardener is different. So there’s no one-size-fits-all answer when it comes to the best location for a kitchen garden.

But my top advice is to think about how you use your yard. Here are questions to think about:

Can it be somewhere close to the house if you want to dart outside for ingredients?

Do you want to see the kitchen garden from the house?

Where do you have growing space available?

Where in your yard are the growing conditions suited to a garden?

Kitchen Garden Plants

My own kitchen garden has annual vegetables, perennial vegetables, herbs, edible flowers, cut flowers, and fruit trees.

I’m a big believer in weaving flowers into a garden. They looks nice. They attracts pollinators. And they attract beneficial insects (small parasites and predators that help to keep pest populations in check.)

A summer succession crop of lettuce between established cabbage and artichoke crops.

Some crops (e.g. lettuce) don’t last the whole season. As you choose crops, take these short-lived crops into account and plan for succession crops to follow them. (Here’s a guide to succession crops.)

Most importantly, grow things you like to eat. Then add in a few new crops to broaden your palate.

Interested in edible perennials? Check out these edible perennials.

Growing vegetable crops in containers? Here are my favourite container vegetable crops.

Kitchen Garden Layout

How to Start a Kitchen Garden

Layout is a personal thing. I geek out at the mention of traditional French potager gardens.

My kitchen garden doesn’t look quite like a potager—but I took inspiration from that style as I added brick walkways, terracotta pots, and a mix of edibles and flowers for cutting.

Your kitchen garden layout might include raised beds, a cold frame, and large containers. It's up to you.

What is a Potager Garden?

Pin this post!

Think of it as a traditional French kitchen garden. Potager gardens blend colourful flowers, salad greens, fresh fruits, and herbs. There's often symmetry. There's often a focal point.

Oklahoma garden designer Linda Vater loves to create elegant edible gardens. Her work is inspired by the tradition of the potager garden. Get Linda’s tips for making an elegant edible garden.

I love this: Landscape architect Jennifer Bartley says, “The potager is more than a kitchen garden; it is a philosophy of living that is dependent on the seasons and the immediacy of the garden.” Get Jennifer’s tips for designing a kitchen garden.

Spacing in a Kitchen Garden

Experiment with Spacing

Recommendations on seed packets are often geared towards field-scale production, and towards fully mature crops. If you’re planning to harvest baby lettuce, it needs less space than a large, mature head of lettuce.

Another way to look at spacing is through the lens of rows versus blocks. I talk about rows and blocks in this article with 7 garden layout ideas.

Top Kitchen Garden Tip

Be wildly creative.

More Fun Theme Gardens

Fun Kitchen Garden Ideas for Kids (and Adults too!)

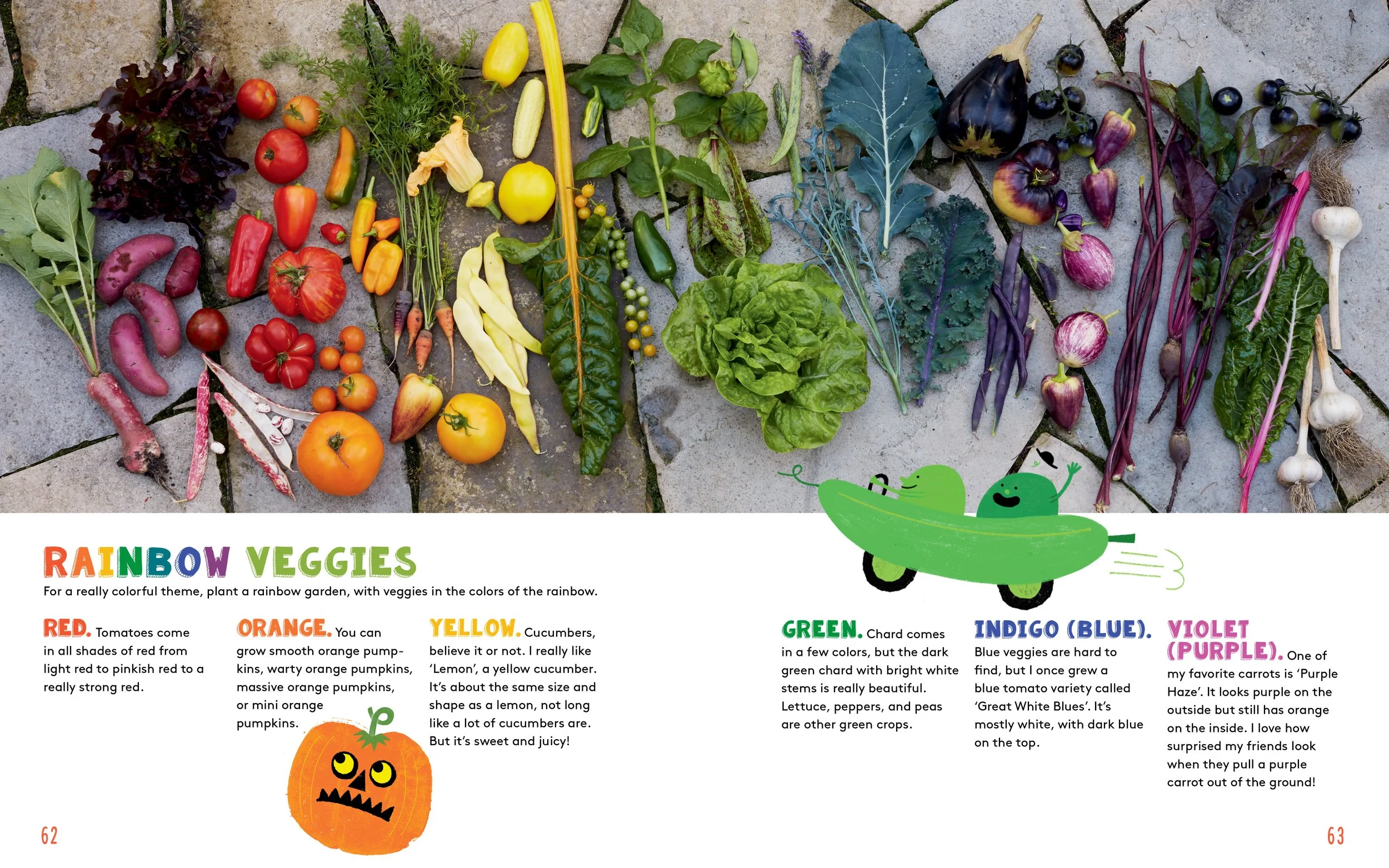

In Gardening with Emma, my daughter has a rainbow spread of veggies. Perhaps a rainbow planting in your kitchen garden?

From the book Gardening with Emma.

How About a Dragon-Themed Garden?

Emma and I gave a talk about kids gardening once and the next day a parent emailed to say that her son came home inspired to grow a dragon-themed garden!

Any kids you want to inspire to garden? Get ideas for dragon-themed plants.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More Kitchen Gardening Ideas

Articles and Interviews

For more posts about how to grow vegetables and kitchen garden design, head over to the vegetable gardening home page.

Courses: Edible Gardening

Want more ideas to make a great kitchen garden? We have great online classes that you can work through at your own pace.

Kitchen Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your kitchen garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

How to Grow Currants - A Great Fruit for a Home Garden

How to grow currants

By Steven Biggs

A Neglected Currant Bush

Red currants are easy to grow, making them well suited to home gardens.

A lonely red currant bush under the apple tree next door showed me currants are a perfect fruit for home gardens.

That forlorn currant bush had been untended for years, growing in shade and heavy clay soil.

It had a lot going against it. Yet it reliably grew currants every year…and when they went unpicked, I reached through the fence to harvest them.

Why Grow Currants?

Currants are a great fit for home gardens for a few reasons:

They are easy to grow

They tolerate the less-than-perfect conditions of a home garden

They produce fruit even when neglected

They are versatile in the kitchen (syrups, jellies, cordials, compotes)

The fruit is rarely sold at stores (and expensive if you find it)

Despite all of these reasons to grow currants, they are less common here in North America than in Europe, where they are a garden staple. Keep reading to find out how to grow this versatile fruit in a garden, edible landscape, or food forest.

Currant Fruit

Black currants, red currants, and clove currants are all different species. There are some differences in pruning, but they’re all simple to grow and can be planted together.

Black currants have an intense flavour…people usually love them or hate them!