Shopping for Nut Trees? Find Out Where to Buy Nut Trees and Nut Bushes

Where to find nut trees and nut bushes for sale.

By Steven Biggs

Nut Tree Nursery List

I get a lot of messages from people looking for more edible plants for their home gardens and edible landscapes. So I hope this list of nurseries that sells nut trees and nut bushes helps you find the plant you’re looking for.

This list focuses on nurseries, garden centres, and specialty nut growers in Canada and the northern USA.

It’s a work in progress. If there’s a nursery you recommend, please e-mail me to let me know.

Before you browse nut tree nurseries, get started with Nut Tree Shopping Tips, below.

Tips When Plant Shopping

Here are tips to keep in mind as you get ready to order trees and shrubs.

Delivery vs. Pick-Up

It’s expensive to ship trees and shrubs! They’re big. And if there’s soil—they’re heavy too.

Delivery costs depend on the distance, the size of the plant, and whether it’s in a pot with soil, or is “bare root.”

(Bare root means it’s dormant, and there’s no soil.)

If picking up your fruit plants is an option, you can usually save quite a bit of money.

Ordering and Shipping Fruit Trees and shrubs

Shipping usually begins in spring, when there’s no further risk to the plants from cold temperatures.

The first to ship are “bare root” plants—dormant shrubs and trees with no soil. (Roots are wrapped in something damp to prevent them from drying out.)

Cross-Border Shipments

Some sellers don’t ship out of country. That’s because it usually involves “phytosanitary” inspections and paperwork.

Or, there might be restrictions on shipping some types of fruit to some regions (to avoid the spread of pests or diseases.)

If you find an out-of-country vendor who ships to your country, ask about the cost of phytosanitary certificates—as well as the delay that inspections can cause for your shipment.

When You Receive Your Order

Bare-root Plants. Keep them somewhere cool and dark until you’re ready to plant them, so that they remain dormant. Plant as soon as possible. Make sure the roots stay moist.

Potted Plants. There’s less of a rush planting potted plants than there is with bare-root plants. Keep plants well-watered until they’re planted.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Canada Nut Tree Nurseries

Pin this post!

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Hardy fruit, exotic fruit, and nuts.

Hardy Fruit Tree Nursery

Rawdon, Quebec

Hold-hardy nut trees, nut bushes, and a wide mix of fruiting plants.

Grimo Nut Nursery

We get Ontario grown pecans here! They sell a wide range of nut trees and nut bushes, along with some minor fruit.

Founder Ernie Grimo joined us on The Food Garden Life Show to talk about cold-adapted nut trees. Tune in here.

Nutcracker Nursery

Maskinongé, Quebec

As the name suggests, nut trees is a specialty. I’ve ordered plums and damsons here and was pleased with the quality of the plants.

Pépeinière Ancestrale

St-Julien, Quebec

Good mix of nut trees and nut bushes. This is where I got my first cherry-plum bushes. Fruit and nut trees.

Prairie Hardy Nursery

Two Hills, Alberta

Recommended by my horticultural colleague in Alberta Donna Balzer.

Rhora's Nut Farm and Nursery

Wainfleet, Ontario

Specializing in nut trees and minor fruit.

Silvercreek Nursery

Wellesley, Ontario

Nuts and fruit. Some of my apple trees are from Silvercreek—and I took a fantastic grafting workshop there.

Whiffletree Farm and Nursery

Elora, Ontario

Nut trees, nut bushes, fruit trees and bushes, and orchard supplies.

Willow Creek Permaculture

Dutton, Ontario

Fruit and nut trees.

USA Nut Tree Nurseries

One Green World

Portland, Oregon

Nut trees and bushes, fruit, subtropical fruits, fruiting ground covers. We chatted with Sam Hubert from One Green World on the podcast to find out all about hardy citrus. They carry lots of other fruit trees, fruit bushes, and berries too.

Raintree Nursery

Morton, Washington

A diverse collections of edible plants including nut trees and nut bushes.

More Sources for Plants

More on Growing Food at Home

Head to the Library for articles, interviews, and guides on how to grow fruit, nuts, vegetables, herbs, and more at home.

Prevent Leggy Seedlings and Grow Vegetable Transplants Like an Expert

The best way to solve the problem of spindly seedlings is to prevent them from getting that way in the first place. Find out how.

By Steven Biggs

Your Seedlings are Leggy? Keep Reading!

If your seedlings are doing the downward dog, this post is for you.

When young seedlings are so fragile that they fold into two, they don’t stand a good chance of success once you transplant them into the garden.

Yet leggy seedlings is a common problem for home gardeners starting seeds indoors. That’s because in a home setting, conditions are often less than ideal.

But there’s good news.

Even if you don’t have perfect conditions—even if you don’t have a greenhouse—you can grow healthy seedlings that will thrive. It’s just a matter of setting up your seed-starting area so you can give small seedlings:

An appropriate temperature

Enough light

A suitable potting soil

Combine these with a suitable container, and you’re away to the races. You can grow strong and healthy plants.

This article tells you how much light you need, what you need to know about temperature, what to look for (and avoid!) in a potting soil, and how to choose a suitable container. Get these four things right, and you’ll prevent leggy seedlings.

Heat to Sow Seeds Indoors

Warmer than room temperature to germinate, cooler than room temperature after germination.

If you see different seed-starting temperature recommendations for different crops, don’t sweat it. You’re probably starting all of your different crops in the same indoor space anyway.

Here’s the big picture, a simple way to think about temperature:

When you start seeds indoors, a temperature a bit above room temperature is helpful for faster, uniform germination

Once your seeds germinate, a temperature slightly cooler than room temperature helps to keep your seedlings more compact

Higher Temperature for Germination

Speed up germination with more heat. Seed tray beside a heat duct to speed up germination.

You can raise the soil temperature without turning your house into a tropical conservatory. Just use what’s called “bottom heat.”

Bottom heat refers to heating the soil from below. There are purpose-made heat mats, like heating pads for plants, that go underneath pots and trays. With a heat mat, you’re only heating a small area.

Here are other ways you might be able to give your seeds bottom heat:

Heated floor

Hot-water radiator

An appliance that gives off heat (my former beer fridge was always warm on top)

In a previous house, I put seed trays beside basement heat ducts (over top of my wine rack!) to get seeds to germinate quickly. They sprouted seedlings faster than the trays in a cooler location.

Hold in Heat

Along with heat from the bottom, hold in heat and keep the humidity higher during the germination period. There are commercially available humidity domes for trays, or you can use clear plastic bags or cling wrap.

Cooler Temperature for Growing

Once seeds have germinated, a cooler temperature helps to develop sturdy stems. So remove the heat mat if you’re using one, and if you’re using a cover, set it ajar to let out some heat and humidity.

I grow seeds in a basement room with the heat ducts closed. It’s slightly cooler than the rest of the house and the temperature works well for raising seedlings.

Sufficient Light

Insufficient light is one of the things that will cause lanky seedlings.

There's a wide variety of grow lights available for home gardeners. But if you’re growing vegetable transplants indoors, you don’t need fancy grow lights. That’s because you’re not trying to grow the crop indoors for its entire life cycle.

All you’re trying to do is to get a healthy seedling to transplant into the garden. And once it’s in the garden, it gets full sunlight.

Grow Lights

Adequate light is important; but there’s no need for perfect light because seedlings get full sunlight when moved to the garden.

I still use fluorescent lights because that's what I have and I'm on a limited budget. You can buy fancy schmancy lights; there’s no need.

If you’re using artificial light, consider the distance of the seedling from the grow light. Some grow lights have adjustable lights that can be moved close to seedlings, and then moved up as seedlings get taller.

If, like me, you don't have that option, place something under the seedlings to raise them up, closer to the light source. (Mandarin orange crates work well in my setup!) As the plants get bigger, lower them so they’re not touching the lights.

Natural Light

If you’re using natural light, the brightest windows are usually south-facing. One challenge is that south-facing windows can be hot. Warmer temperatures can cause leggy seedlings. A simple solution to this is to place a fan in the area to disperse the heat.

Soil

Even with good light and a suitable temperature, if you have poor-quality soil, your seedlings might flop!

When it comes to soil, the top two things to think about are:

Use a light soil with lots of air space to allow excess water to drain and small roots to grow

Choose soil that’s free from pests and diseases

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Disease in Potting Soil

Little seedlings are delicate and they're vulnerable to attack by disease. In a seed-starting environment, the most common disease is what’s called “damping off” disease. This fungal disease can come with the soil—so one of the easiest ways to prevent the disease is to use soil free from damping off.

Here’s how to lessen the chance of damping off:

Don’t reuse potting soil for starting seeds (unless you’re planning to heat sterilize it)

Don’t use garden compost for seed starting; it has more microbial activity—which is great in the garden—just not ideal for indoor seed-starting

Potting Soil Shopping Tips

Big bales. It’s buyer beware with potting soil. Some potting soils are great…some suck. The large compressed bags (a.k.a. bales) that are sold to commercial growers tend to have consistently better quality because commercial growers are more discerning. Big bales are also much better value. They’re compressed, and often quite dry—so also less likely to have eggs of pesky fungus gnats.

Finely-ground potting soils. There are seed-starting potting soils that are more finely ground, the idea being that big particles can get in the way of small seeds. This makes sense in a commercial setting where uniform, perfect germination is a must. It’s absolutely unnecessary in a home-garden setting. Don’t waste your money.

Skip the meal deal. Seeds germinate and start to grow using energy stored in the seed. Don’t buys soil with added fertilizer; it can actually burn tender seedling roots.

And…If you see soil on special at a big box store for a couple of bucks, remember that a bargain isn’t always a bargain.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Containers

When I worked in the horticultural supply industry we sold various seedling trays, pots, the “cell packs” used in commercial seedling production.

Many of these are available to home gardeners, though not necessary.

The key things to think about with containers:

Drainage holes to allow excess water to drain

Not contaminated with damping off disease (see Reusing Pots and Trays, below)

Plug trays for starting seeds indoors. Not necessary, but useful when you grow lots of the same thing.

Container Type and Size

If you’re growing a lot of one type of seed, you might like to have containers that are the same size because it simplifies watering. When my daughter raised hundreds of tomato seedlings, I got her what’s called “plug trays” so she could grow lots of small plants in our small space. They all had the same amount of soil, and dried out at the same speed.

I don’t use the expanding peat pellets. I think they’re gimmicky.

Use What’s in Your Recycling Bin

I am a big fan of scouring the recycling bin for seedling pots. For example:

Yogurt containers

Mandarin orange crates (my favourite for lettuce seedlings)

Tubs for mushrooms

Using a mandarin orange crate to grow tomato seedlings.

Tips when using recycled containers:

The volume of soil in different containers will vary—so water accordingly

Put holes in the container for drainage

Reusing Pots and Trays

If you're reusing pots and trays, it’s a good idea to first sterilize them to prevent damping off disease. That’s because any soil crusted on the container from the previous year can harbour the disease. If you haven’t had damping off disease in the past you might be OK…but personally, I don’t risk it. So I sterilize them.

When damping off disease attacks seedlings, it can wipe out a whole tray in just a day or two. It can be quite devastating.

Cell packs drying after washing and sterilizing to prevent damping off disease on seedlings.

Here’s what I do to sterilize containers:

Soak containers in water

Scrub off any crusted soil

Place them in a solution of 10 parts water with one part bleach

Let them air dry

What About Fibre Pots?

There are a few types of fibre-based biodegradable pots. Recently I saw some made from cow dung! Some people make newspaper pots, or reuse toilet paper rolls for seed starting. In principle, you can plant these pots straight into the ground, but there are a couple of caveats.

The pots wick out moisture, away from plant roots…and they can dry out quickly. So watch the soil moisture to make sure that it doesn't get too dry for your seedlings.

Later, when you transplant seedlings in the garden, if the lip of the pot is above the soil level, it'll wick the water away from around the roots, so the soil around the roots can be drier than the garden soil. So tear off the top of the pot—or bury it. That solves the wicking problem.

FAQ – Leggy Seedlings

Can you fix leggy seedlings? Can leggy seedlings recover? Can you fix stretched seedlings?

You can’t correct leggy seedlings...but if the seedlings aren’t too far gone, you can change the growing conditions so that the seedlings grow thicker stems.

Why are my seedlings flopping over? Why is my plant growing tall and skinny?

It can be too little light, too much heat, excess moisture—or a combination of these.

Can I bury leggy seedlings deeper? Can I fix leggy tomato seedlings?

In many cases, no. First of all, very thin stems can easily be crushed. And most seedlings don’t do well when planted deeper than the level they’re been growing at. Leggy tomato seedlings can be an exception—they do well when planted deeper—but it will depend how long, skinny, and delicate the spindly seedling is. Better to avoid the leggy seedlings in the first place!

Find Out About About Seed Starting in this Podcast

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Vegetable Seeds

More on Growing Vegetables

Vegetable Gardening Articles and Interviews

For more posts about how to grow vegetables and kitchen garden design, head over to the vegetable gardening home page.

Vegetable Gardening Courses

Want more ideas to make a great kitchen garden? We have great online classes that you can work through at your own pace.

Seed Shopping Smarts: Know The Lingo So You Can Get The Best Seeds

What’s your seed-shopping vocabulary like? Brush up on your seed lingo in this glossary of seed terminology so you can choose the best seeds for your needs.

By Steven Biggs

Best Seeds for Your Needs When You Know The Lingo

Get the best seeds for you needs when you know seed terminology.

When I worked at a marketing and communications company, there was a linguistic divide in our office.

The in-house application developers had a vocabulary that was incomprehensible to those of us working the phones.

As an outsider who wasn’t too tech savvy, it took me a while to absorb the new vocabulary.

Specialized Seed Vocabulary

It’s easy to feel like an outsider when you encounter specialized lingo. And it’s not just in the tech sector. (My father-in-law doesn’t realize I miss most of what he’s telling me when he shows me under the hood of his car…and now I have a son who has a whole vocabulary around mountain biking!)

Gardening has specialized vocabulary too. And I’ll be glad if you find this this glossary of seed terminology helpful in choosing the best seeds for your garden.

Glossary of Seed Terminology

Here are common terms that you’ll find when you seed shop. Knowing what they mean will help you get the best seeds for your situation.

This glossary of seed terminology will explain important seed vocabulary.

Annual

An annual plant has a one-year life cycle. It flowers makes seed, and dies in one year. Common annuals include veggies such as beans, lettuce, and spinach.

(To confuse things, some of the so-called annual flowers that we grow in northern gardens live more than one year in warmer climates—but die in our cold winters, so we treat them as annuals. But actually, they’re not. A good example is fuchsia.)

Biennial

A biennial has a two-year life cycle. The first year, it makes leaves; and in the second year, flowers and seeds. In the veggie garden, a number of common crops are biennials, but we usually harvest from them during the first year. Parsley, Swiss chard, and carrots are examples.

Botanical Name (Scientific Name, Latin Name)

This is the official two-part name, often italicized. Useful when we want to make sure there’s no confusion around what plant we’re dealing with.

Common Name

This is the everyday, plain English name. The only problem is that sometimes the same name gets used on more than one plant. Bluebell is a good example. That’s why, when in doubt, you can check the Botanical Name to make sure you’re ordering what you want.

Cotyledon

This is the name of the first leaves that emerge when a seed germinates. You might see this word when seed shopping because transplanting guides often talk about “seed leaves” or “cotyledon leaves” when explaining when to transplant your seedlings. They look different from the “true” leaves that come afterwards.

Many common garden crops are biennials. Parsnip (seeds at the top) is a good example of a biennial in the vegetable garden.

Cultivar

This word comes from “cultivated variety.” It just means a variety intentionally grown by humans. People often use this term interchangeably with “variety” although there are also naturally occurring plant varieties—which is why the distinction. If you see a name between single quotes (‘ ‘) it’s likely a cultivar name. A cultivar can be an open-pollinated or a hybrid (see below).

Days to Maturity (Days to Harvest)

An approximate number of days until harvest. This number is always approximate because many things (weather, growing conditions, the stage of harvest) have an effect on it.

For crops we plant directly in the garden, it’s the number of days from seeding until harvest; while for crops we start indoors as transplants (e.g. tomatoes) it the number of days from transplanting in the garden until harvest.

Dioecious

Dioecious plants have male and female flowers on separate plants. In the veggie garden, asparagus is an example of a dioecious plant.

Direct Sow (Direct Seed)

Pea seeds, an example of a crop that we usually direct sow.

This is when we plant seeds in their final, outdoor destination. Crops that are commonly direct seeded include root crops such as carrots, beets, as well as beans and peas.

Germination Rate

Seed companies test germination. (At least I hope they do!) If you see a percentage on a seed packet, it indicates the germination rate from a germination test—and this should give you an idea of what sort of germination you can expect at home under good conditions.

GMO (Genetically Modified Organism)

Many people understand this to mean a plant into which genetic material from another plant or life form is inserted. What’s confusing is that the way this term is often understood and the official definitions differ.

The exact definition depends on who you ask and where you are. Here’s the official definition used by the Government of Canada.

“A genetically modified (GM) food is a food that comes from an organism (plant, animal or microorganism) that has had 1 or more of its characteristics changed on purpose. Organisms can be modified by different processes, including: conventional breeding techniques, like cross-breeding or mutagenesis (a change in the genetic make-up of an organism caused by chemicals or radiation); modern biotechnology techniques, such as genetic engineering; gene editing.”

Here’s what can be confusing: The wordy definition above includes traditional breeding…the sort of breeding that might have given us some of our heirloom varieties. What many people want to avoid is “genetically engineered” seeds. Genetically engineered seeds are mostly found in commodity crops (think canola and corn) – and are not sold to home gardeners.

Harden Off

When seedlings are moved from protected conditions such as indoor grow lights or a greenhouse, they are “hardened off,” which means they are gradually acclimated to the brighter light, different temperatures, and wind outdoors.

Hardy Annual

An annual that tolerates some frost and cool conditions. For example, a common hardy annual vegetable is arugula—which, if you let it make seed, you’re likely to find growing up on its own in your garden while there are still cool conditions.

Heirloom

Like the word “natural” in the health food sector, “heirloom” is one of those fuzzy, poorly defined words that marketers adore. There’s no precise meaning. But, in general, it means an older open-pollinated variety.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Hybrid Seeds

Hybrid seeds result from cross-pollinating two varieties with desirable traits. In the seed industry, it’s done in controlled conditions, so there’s no chance of an errant pollen grain giving something different.

Hybrid seeds tend to be more expensive because of the labour needed to make the cross. Hybrids are often made to have desirable traits such as disease resistance and vigour…and they’re also made because it’s an industry.

If you see the term “F1,” that refers to the first generation of seed after the cross. That’s usually what’s for sale at seed vendors. When you save seeds from a hybrid plant, it will probably be different from the parent plant.

Hybrids occur in nature too, but the hybrid seeds you find at vendors will have been deliberate. When people are new to seed shopping they sometimes wonder if hybrid has something to do with genetic engineering—and it doesn’t. It’s entirely different.

Last Frost Date (Average Last Frost Date)

The date in the spring when—on average—there isn’t any more frost in your area. It’s figured out using historical weather data.

This date is like a marker post for seed sowing. When a seed catalogue recommends starting tomato seeds 8 weeks before your average last frost date, this is what it’s referring to.

This date is also used when deciding when to move seedlings into the garden. (But remember…an average last frost date means that some years there is frost after that date.)

Monoecious

Monoecious plants have both male and female flowers on the same plant. Melons are monoecious; and if you look closely, you’ll see some of the flowers have little melons-in-waiting next to the female flowers, while the male flowers have none.

Open Pollinated (OP)

Open-pollinated bean varieties are easy to save seeds from because there is not usually much cross-pollination with other varieties.

Open-pollinated varieties are stable varieties that you can save seed from and get plants that are like the parent plants. Some open-pollinated varieties are heirlooms; some are recent.

Note: To get seeds like the parent plant, there can’t be “cross-pollination” with other varieties. Some types of plants mostly self-pollinate (they have perfect flowers, see below), so you’re likely to get seeds like the parent plant without doing anything special. But some plants have separate male and female flowers—meaning insects might pollinate them with pollen from another variety. Squash is a good example. In that case, open-pollinated varieties are grown in isolation when saving seed.

Organic

Generally understood to mean that the plants the seeds are harvested from are not treated with synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. The thing to keep in mind when seed shopping (food shopping, too, actually) is that there are organic certification bodies—agencies that make sure a producer adheres to a set of standards. So you might come across seed that a seller says is organic—but is not “certified” organic.

Parthenocarpic

This refers to varieties that can make fruit without pollination. The resulting fruit has no seeds. You’re most likely to see this term as you browse cucumber varieties.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Pelleted

Sometimes small or irregularly shaped seeds are coated with clay to make them easier to handle or dispense with seeding equipment. These “pelleted” seeds are usually more expensive.

Perennial

A plant with a life cycle spanning a number of years.

Perfect Flower

A flower that has both male and female parts.

Set

Onion “sets” are small, pre-grown onion bulbs that you can plant directly in the garden instead of growing onion seedlings. It’s a great option if you don’t have a lot of indoor space for growing onion transplants.

Tender Annual

An annual plant that does not tolerate frost. We usually start tender annuals indoors, in warm conditions, and then transplant them outdoors when there is no further risk of frost. A good example of a tender annual is basil…which quickly wilts in protest in cool weather.

Transplant

Tomato seedlings, or “transplants.” We use the word transplant as both a noun and a verb.

The word we sometimes use to refer to the little seedlings that we start indoors. Of course, it’s also the act of replanting—transplanting—the little seedings. So both a noun and a verb!

Treated Seed

If you’ve ever seen a pink pea or bean seed, it’s been treated with a fungicide. That treatment is done to prevent rot in cold, wet soil. If you don’t seed that’s treated, look for “untreated” seed.

Untreated Seed

Seed that has not been treated.

Crop-Specific Lingo

Beans

Pin this post!

Bush bean plants are shorter, and tend to have an earlier and briefer period of harvest. Depending on the variety, they might or might not need support.

Pole and runner beans get quite tall, and will need support. The harvest is later, and the harvest period is longer.

Peas

Vining pea varieties, like runner and pole beans, get quite tall and have a longer harvest window.

Squash

Bush squash are compact (at least for a squash plant!).

Vining (running) squash have long stems that spread far and wide.

Tomato

Determinate (bush, patio) tomato plants get to a certain size and then stop growing. They are relatively compact, and flower and fruit in a shorter time. Even thought they are compact, they are not self supporting—so if you like your tomato plants off the ground, use a stake or a cage.

Indeterminate (vining) tomato plants keep growing and making fruit as long as conditions permit. They get very tall if the growing season permits. (This is the sort of tomato used in greenhouse tomato production here in Ontario: Plants are grown up twine, and as they get taller and taller, the twine is lowered and the base of the stem is coiled on the ground.)

There are also semi-determinate tomato varieties.

Find Out about Seed Shopping in this Podcast

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Vegetable Seeds

More on Growing Vegetables

Vegetable Gardening Articles

Vegetable Gardening Courses

Looking for Lemon Trees? Find Out Where to Buy Rare and Hardy Citrus Trees

Find out where to buy a lemon tree.

By Steven Biggs

Looking for Lemon Trees? Find Out Where to Buy Citrus Trees

I get a lot of messages from people wondering where to buy a lemon tree. So I hope this list of nurseries selling lemon trees and other citrus trees helps you find what you’re looking for.

This list focuses on nurseries, garden centres, and citrus-growing specialists in Canada and the northern USA.

It’s a work in progress. If there’s a citrus nursery or garden centre that sells lemon trees near you, please e-mail me to let me know.

Before you browse through the list, get started with Tips When Shopping for a Lemon Tree, below.

Tips When Shopping for a Lemon Tree

Here are tips to keep in mind as you get ready to shop for a lemon tree or other citrus trees.

Delivery vs. Pick-Up

Larger potted plants can be expensive to ship! Delivery costs depend on the distance and the size of the citrus trees.

If picking up your citrus trees is an option, you can usually save quite a bit of money.

Mail-order sellers usually only ship spring through fall, when the temperature is warm enough.

Seasonal Lemon Tree Availability

Some of the sellers listed here are nurseries that propagate their own citrus and have plants year-round.

Others are garden centres that carry lemon trees and other citrus trees seasonally.

Here in Southern Ontario, I often start to see California-grown potted citrus trees in garden centres in the spring. Selection usually declines through the season, and once they’re sold out, that’s it until the following year.

Cross-Border Shipments

Some nurseries and garden centres don’t ship citrus trees out of country. That’s because sending plants across the border involves inspections and paperwork.

If you find an out-of-country vendor who does ship to your area, ask about any additional cost for inspections and paperwork. Ask, too, about the delay that inspections could cause for your shipment of citrus trees.

Canada Lemon Trees and Other Citrus Trees

Angelo’s Garden Centre

Vaughan, Ontario

This is a garden centre near me, in the Toronto area, that seasonally carries citrus trees, olive trees, and fig trees. (I got my first olive tree here!) Hear owner Carlo Amendolia tell the story of their 19-foot-high fig tree.

Brugmansia Quebec

St-Valérien de Milton, Québec

A good selection of citrus trees, figs, and, as the name suggests, Brugmansia—a.k.a. angel’s trumpet.

Exotic Fruit Nursery

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Citrus trees, hardy fruit trees, exotic fruit, and nut trees.

Fiesta Gardens

Toronto, Ontario

We’re big fans of Fiesta Gardens, here in Toronto. This independent garden centre brings in some really cool plant material every year—and there are usually lemon trees and other citrus too.

Fruit Trees and More

North Saanich, British Columbia

This nursery and demonstration orchard specializes in plants for Mediterranean climates. Owner Bob Duncan was the inspiration for my book Grow Lemons Where You Think You Can’t. He grow citrus tree espaliers in his demonstration orchard, and has a big Meyer lemon espalier on his house.

Nutcracker Nursery

Maskinongé, Quebec

Nice selection of citrus trees and figs. As the name suggests, they specialize in nuts. Also other fruit (I’ve ordered plums and damsons here and was pleased with the quality of the plants.)

Phoenix Perennials

Richmond, British Columbia

An excellent mail-order nursery with unusual plants. (This is where I tracked down a grafted tomato-potato plant for my daughter!) They have a good selection of citrus trees.

Sage Garden Greenhouses

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Co-owner Dave Hanson has joined me to teach about exotic edibles and Mediterranean plants. He is a wealth of knowledge.

Tropic of Canada

Rodney, Ontario

Citrus, figs, and a fun mix of exotics.

Valleyview Gardens

Markham, Ontario

This Toronto-area garden centre has tropical plants year-round. When I couldn’t find a yuzu citrus tree, this is where I found one.

USA Lemon Trees and Other Citrus Trees

Edible Landscaping

Afton, Virginia

Citrus, fruit trees, fruit bushes, berries, and exotics.

Four Winds Growers

Winters, California

Specializes in semi-dwarf citrus trees.

Logee’s

Danielson, Connecticut

As well as citrus, they have figs and other exotic fruit—and a ton of ornamentals. Their ponderosa lemon is over 100 years old!

McKenzie Farm

Scranton, South Carolina

Owner Stan McKenzie is passionate about cold-hardy citrus. Hear Stan tell us all about cold-hardy citrus on The Food Garden Life Show.

One Green World

Portland, Oregon

A delicious mix of citrus trees, olives, figs, and lots of sub-tropical fruit.

Sam Hubert from One Green World joined us on the Food Garden Life show with top cold-hardy citrus picks. Find out Sam’s favourite cold-hardy citrus.

Well-Sweep Herb Farm

Port Murray, New Jersey

Lots of herbs, and a good selection of citrus.

Damson Plums: This Forgotten Fruit Combines Dry, Sweet, Spicy, and Bitter (and it’s a perfect home-garden crop)

Find out how to grow this forgotten fruit that has a rich, complex flavour. It’s a gem in the kitchen, and easy to grow in a home garden.

By Steven Biggs

Disappearing Damsons

I remember when Nana started to ration the jam. The damson jam.

She was running low on her homemade damson jam. And what was left was reserved for damson tarts—one of her specialties.

She couldn’t get damsons any more.

Why the fuss? Because damsons have a special flavour and make marvellous jam. They’re the ultimate plum for cooking, with a rich, complex flavour that combines sweet, spicy, slightly sour, and a touch of bitter.

I was just a kid at the time. Since then, I’ve rarely seen damson fruit or damson trees for sale. Too bad, because it’s a unique fruit that’s well worth a place in a home garden.

But they’re not completely forgotten.

When I drove through the Kamouraska region of Quebec, I took a detour especially to visit Maison de la Prune, a small damson orchard and museum in what was once a major damson production area. I came home with damson syrup, and sweet and savoury jellies.

Keep reading to find out more about this special plum, and how to successfully grow it.

Hear a Damson Expert Explain What’s Special About Damsons

What is a Damson Plum?

Damsons (Prunus insititia) are smaller and not as sweet as their cousin the European plum (Prunus domestica). (Quick plum primer…it’s a big family, including Japanese plums, P. salicina, North American plums, P. americana, and the cherry plum, P. cerasifera.)

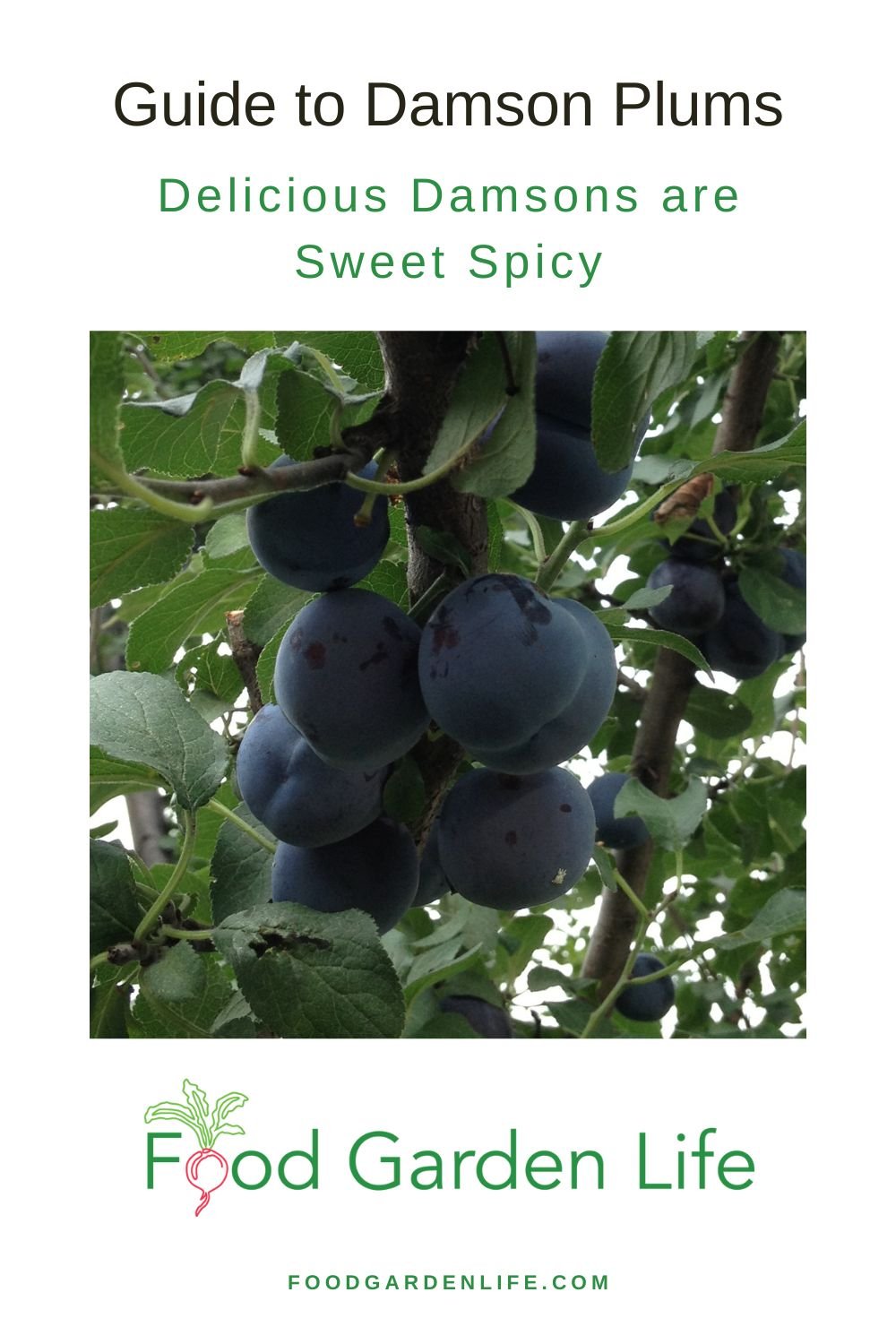

A damson is a small, oval-shaped plum. The skin is often a deep blue-purple colour, with yellow flesh, although there are also yellow-skinned varieties. They’re a “clingstone” fruit, meaning that the flesh, which is quite firm, is attached to the stone. Like many fruit in the plum family, the fruit has a waxy “bloom” on it, giving fresh damsons a silvery hue.

Damsons are self-fertile—meaning only one tree is needed to get fruit. They bloom in early spring, with fruit starting to ripen in late summer.

How are Damsons Different From Other Plums?

The damson is smaller than the European plum. These damsons will ripen to a purple colour.

When it comes to the plant itself, the trees have a more compact growth than other domestic plums, developing a gnarled shapes as they get older.

The fruit is smaller too, with more stone and less fruit than other domestic plums—up to one third stone. The fruit is also drier than European plums and Japanese plums.

While damsons are sweet, they’re also slightly astringent, giving them a complex flavour and making them superb for cooking. (Perhaps less attractive for fresh eating, though I love them.)

Along with the astringency comes a spiciness and sweetness that sets them apart from domestic plums.

What is a Bullace?

It’s worth noting a couple of other relatives that are sometimes included when talking about damsons. Along with damsons, Prunus insititia includes bullaces, and St. Julian plums.

St. Julian plum is mostly grown as a rootstock for grafting damsons

The round bullace fruit is smaller than damsons, ripening later, and has a less complex flavour

The bullace is different from the sloe (Prunus spinosa) which is bushier. If the sloe is new to you, look up sloe gin. (I know of sloes because my dad had a bottle of sloe gin when I was growing up.)

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

How to Grow Damsons

Planting Damsons

The first thing to know is that damsons are self-fertile. This means that you can plant one damson tree and get fruit.

Like other fruit that flower early—while there’s still a risk of frost—choose a location where there’s less chance of flowers getting hit by frost. This means:

Avoid low-lying pockets that get heavy frost when other parts of your garden don’t

If you’re in an area with late spring frosts, a north-west-facing slope can be safer than a south-facing slope (it might seem counter-intuitive…but they’ll bloom earlier on a south-facing slope, meaning more chance of frost damage)

Hear a fruit expert talk about site selection in cold climates.

Where to Plant a Damson Tree

Full sun is best for damsons. They tolerate semi-shade if that’s all you have.

Damsons grow in a wide range of soil types. Avoid acidic soils and soils that dry quickly—meaning sandy soils.

Stake newly planted trees for a year to prevent shifting.

Spacing When Planting Damsons

Damsons are a relatively small tree.

Here are a couple of considerations when deciding on spacing between damson trees:

With grafted trees, the tree size and optimal spacing depends on the rootstock

Space between trees allows air flow, which helps reduce disease pressure

In a home garden setting, there are often competing needs for a small space. In that case, you might want to be creative with spacing. For example:

Plant more than one damson tree in a hole – a clump of damsons

How to Care for Damson Plums

Below is more information about how to care for damsons. But to sum it up quickly in case you’re already a fruit grower: Treat damsons as you would other plums.

How to Prune Damson Plum Trees

Damson fruit in mid summer. They have a golden-yellow flesh when ripe.

If you’re growing damsons in a hedge, you might take a hands-off approach to pruning.

When you’re growing damsons as separate trees, use pruning to shape the tree into a framework of branches that gives good strength, and allows air circulation and ease of picking.

A tree from a nursery might already have a framework developed. If it’s a young tree, you can develop the framework of branches yourself. Damsons can be formed into central-leader style trees, vase-shaped trees, or into a bush. For a bush, picture a short trunk, with branches coming out above that.

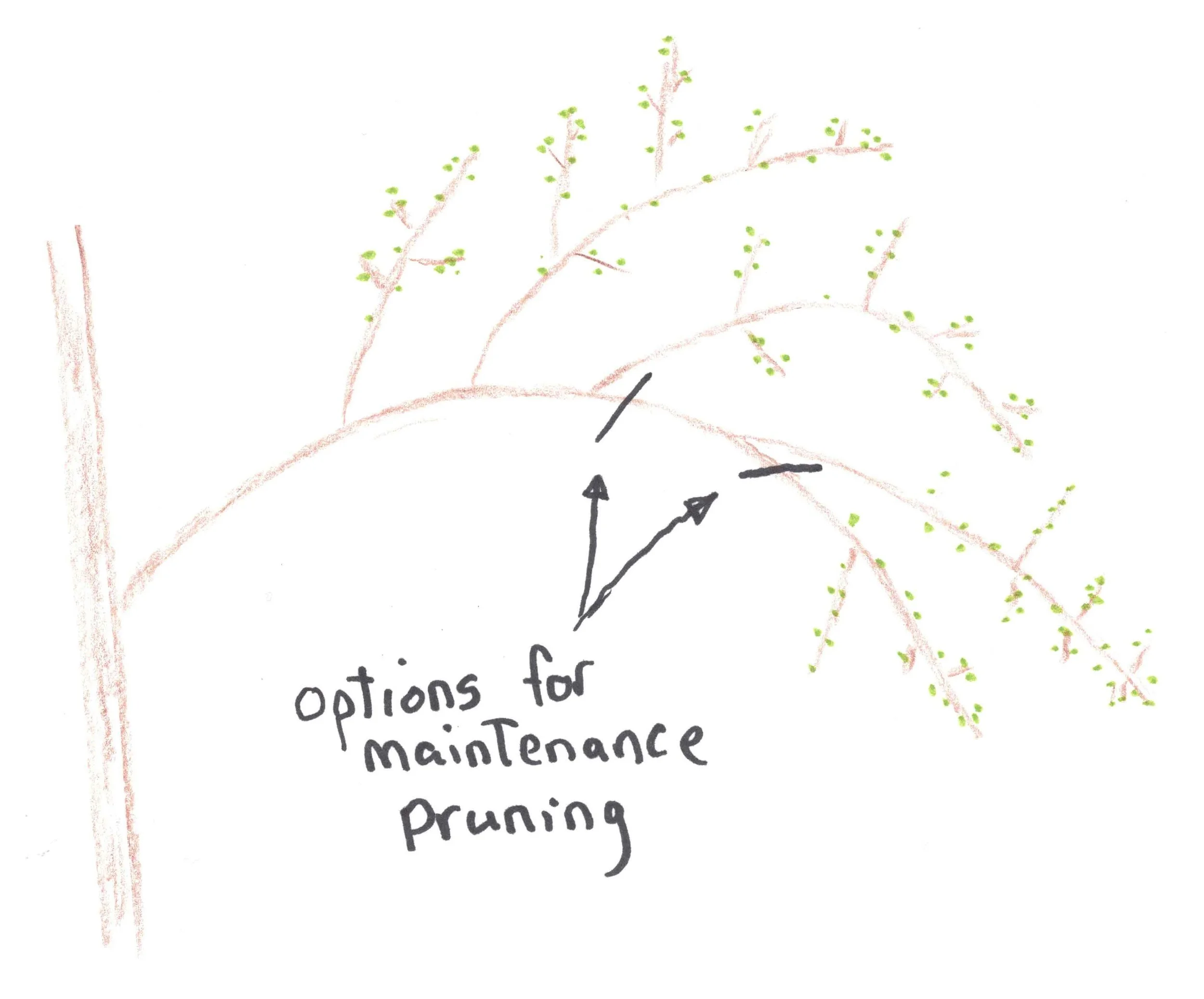

Pruning fruit trees is an entire article unto itself, but here are top tips:

Avoid narrow, v-shaped angles

Don’t make sloppy cuts that leave a nub of branch beyond a bud

Remove crossing branches

Aim to keep the canopy of the tree open, to allow air movement

Like other stone fruit, damsons don’t respond well to attempts to train them into cordons.

Prune in late winter.

Protecting Damson Blossoms from Frost

With a well-chosen site you’re less likely to have frost damage in the spring…but if there is a late frost, and if your damson tree is small enough, a simple cover might protect the blossoms.

Drape the plant with burlap or horticultural fleece. (I’ve even covered tender plants with an old shower curtain!)

Damson Hardiness

Damsons are very cold hardy. There’s no question of hardiness here in my Toronto garden.

I’ve seen Canadian nurseries listing damson varieties hardy into Canadian Plant Hardiness Zone 3, and American nurseries suggesting USDA Zone 5. Here’s a list of nurseries that sell fruit trees.

Consider zones a general guide. Conditions within a zone can vary—and microclimates allow gardeners to push zone boundaries. There can be “frost pockets” in low-lying areas, and moderate areas near large bodies of water.

With grafted plants, hardiness depends on how hardy the top (scion) is—and how hardy the bottom (rootstock) is.

How to Propagate Damson Plums

Damson Seeds and Suckers

In times past, damsons were commercially propagated using seeds and suckers.

Seeds. When grown from seed, many damson varieties “come true,” meaning the new plant is like the parent. If you want to seed-grow damsons, first stratify the seed, and then sow in a pot or directly in the garden.

Suckers. Suckers are the shoots that come from the base of a mature plant, and already have roots. This is an easy way to get started if you know that the tree is not grafted. (If it’s a grafted tree, a sucker might actually be coming from the rootstock.)

Grafting Damsons

Most commercially produced damsons are propagated by grafting.

Under some conditions, damson trees can grow up to 6 metres (20’) tall. But if conditions are not as good—or if trees are grafted onto a rootstock that restricts growth—they’ll be smaller.

This means that it’s good to know how rootstock can affect damson tree size.

Here are common damson rootstock:

Large. Myrobalan B, Brompton

Medium. St Julian A

Small. Pixy, VVA-1

Damson Harvest

Pick damsons as they develop colour and as the fruit becomes softer to the touch.

Damsons ripen in late summer and early fall.

When are Damson Plums Ripe?

Pick as the damsons become soft to the touch. (You can pick them earlier if making gin.)

Why Damsons Sometimes Fruit Every Second Year

It’s common to have what’s called “alternate bearing,” meaning a large crop one year, and then very little—or nothing—the next. This happens because when a fruit tree carries a heavy crop, energy goes to the ripening of that crop—and flower buds are not formed for the next year.

You can prevent alternate bearing by thinning fruit.

Damson Pests and Diseases

Black knot disease.

Mice and rabbits often gnaw on fruit tree bark over the winter. While damson trees are young, use a spiral tree guard around the trunk for the first few winters to protect the bark from rodents.

Black knot is a fungal disease that affects many plants in the plum family, including damsons. Some damson varieties have more black-knot resistance than others. You can recognize black knot by the black, woody growth encircling a branch. (My kids called it poo on a stick when they were little.)

If you see black knot, prune the affected branch back at least 20 cm (8”) below the knot. Don’t leave the pruned-off branch near your damson trees because the knot provides inoculum for more infection.

Damson Recipes

I started off by telling you about my Nana’s damson plum jam. It was so delicious because of the balance that the damsons give, with the combination of fruitiness, sweetness, spiciness, tartness, and a little bit of astringency. Damsons are excellent for jams, fruit butters, and for making fruit cheese because they contain a lot of pectin.

Because they’re “clingstone,” the fruit is usually separated from the stone after cooking.

There are many more ways to use damsons. You’re more likely to come across these in the UK, where there’s a longer tradition of cooking with them.

Damson chutney

Pickled whole damsons

Damson vinegar

Damson gin

Use them where you would use other tart fruits. And think of using them with savoury dishes—not just sweet. That’s because the combined tartness and astringency work well with rich dishes.

(And if you don’t have the time or inclination to spend a lot of time in the kitchen, stewed damsons are a true delight. When I lived in the UK there were damsons in a nearby hedgerow. I’d stew them, cooking with a bit of water and sugar until soft enough to the damson stones. Then I’d eat them with clotted cream.)

For more recipe ideas, I recommend the book Damsons: An Ancient Fruit in the Modern Kitchen.

Where to Buy a Damson Plum Tree

While you might not see damsons at garden centres, specialist fruit tree nurseries often carry them. If ordering online, look for bare-root trees so shipping costs are lower.

Here’s a list of fruit tree nurseries.

The choice of damson varieties in North America tends to be limited. I’ve most often seen damsons sold as Blue Damson.

(You sometimes see them sold as “Damas Bleu,” as there’s also a long history of damson production in Quebec. If you want to delve into that, here’s a fun book: Les Fruits du Québec: Histoire et traditions des douceurs de la table, by Paul-Louis Martin, who is the proprietor of Maison de la Prune that I mentioned earlier.)

In the UK there is a wider selection of damson varieties. I have a 1926 text that lists Blue Prolific, Bradley’s King, Farleigh Prolific, Quetsche, Rivers’ Early, Shropshire Prune, Merryweather. If you search UK nurseries, you’ll see many of these are still available.

Using Damson Trees in Garden Design

Damsons are good choice for a home garden because they are self-fertile. That means that in a small space, you only need one tree to get fruit.

Here are ideas for using damson trees in garden design.

Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

Damsons work well in edible landscapes with a mixed planting of edibles, and in a food-forest setting. Like many fruit trees, they do best in full sun, but tolerate the sort of partial shade that you can get in an urban edible landscape or on the periphery of a food forest.

Home Orchard or Stand-Alone Specimens

A more traditional planting gives each tree enough space to fully develop. The amount of space needed for well developed, well-spaced damson trees depends on the rootstock.

Hedges and Hedgerows

In my own garden, my damsons are part of a fruiting hedge. There are damson and other plum trees in a long row, underplanted with currants and gooseberries. At ground level are strawberries. It’s still rather neat and tidy, but damsons could work well in a less formal hedgerow or windbreak too, mixed with other small fruit.

Here’s a chat with a small fruit specialist to get ideas for less common fruit for a hedge.

FAQ: Damson Plums

How long should I stake a damson tree?

Remove stakes after the damson tree is established and has rooted into the surrounding soil, usually after one season.

Why are so many fruit dropping off in early summer?

There’s a natural fruit drop in early summer. As long as there are lots of fruit remaining on the tree, everything is probably OK.

Do damson trees fruit every year?

Not always. If there’s a heavy crop one year, there might not be a crop the following year. This is called alternate bearing. You can thin fruit to reduce alternate bearing.

What is the botanical name for damsons? Why am I seeing two different botanical names for damsons?

Good question. You might find damsons as Prunus insititia or as Prunus domestica subsp. insititia. That’s because plant taxonomists sometimes rename things.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Fruit Crops

Articles: Grow Fruit

Visit the Grow Fruit home page for more articles about growing fruit.

Here are a few popular articles:

Courses: Grow Fruit

Here are self-paced online courses to help you grow fruit in your home garden.

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Fig Leaf Panna Cotta Recipe

Looking for an easy-to-make, unusual dessert? This is a fig-leaf panna cotta recipe that will have your guests asking for seconds!

By Steven Biggs

An Easy-to-Make Fig-Leaf Recipe

My guests nodded without hesitation when I offered seconds. “Refreshing!” they declared.

Cool, creamy, refreshing fig-leaf panna cotta is a nice way to finish a meal.

(And leftovers are pretty nice for breakfast!)

Cooking with Fig Leaves?

I first learned about cooking with fig leaves when Toronto Chef David Salt got in touch asking for fig leaves. It was October. “Sure,” I said, “Take as many as you’d like, they’ll soon drop.”

Later that fall, David invited me to his restaurant to sample fig-leaf grappa, fig-leaf ice cream, and fig-leaf cheese. (Click here to read about those tasty creations.)

The idea when using fig leaves in cooking is to extract the flavour of the leaves, and then remove them. They’re pretty fibrous, fine to eat if you’re a goat. If you’ve been around figs trees on a warm day and basked in the sweet smell, that’s the flavour we’re pulling from the leaves.

To me the flavour of fig leaves is somewhere between coconut and toasted almond, but with a note of green.

To me the flavour of fig leaves is somewhere between coconut and toasted almond, but with a note of green.

In her book Dandelion & Quince: Exploring the Wide World of Unusual Vegetables, Fruits, and Herbs, author Michelle McKenzie describes flavours of coconut, pear, and vanilla. (She has other fig-leaf recipes too.)

So is a fig leaf a herb? A veg? I’ll leave you to mull that over.

What’s Panna Cotta?

Let’s back up in case panna cotta is new to you. It was to me.

My family culinary tradition includes custard, where sweetened cream is thickened with egg.

In a panna cotta, sweetened cream is thickened using gelatine.

Panna cotta means cooked cream in Italian—so think of it as a custard set with gelatine instead of eggs.

And here’s something interesting: Fig sap causes milk to coagulate, so in this recipe there are two things at play to give you a thick dessert: The effect of the fig sap, and the gelatine.

Where to Get Fig Leaves

If you grow figs, you’re set. If you don’t grow figs, don’t bother to look at the supermarket—you won’t find them. Instead, find a fig grower in your area.

There are more home fig growers around than you might expect, even in cold places. (If you’re looking for fig growers, here’s a fun chat with Toronto Joe on the ourfigs.com about the online fig community, which could be a good way to find fig growers.)

Getting Flavour from Fig Leaves

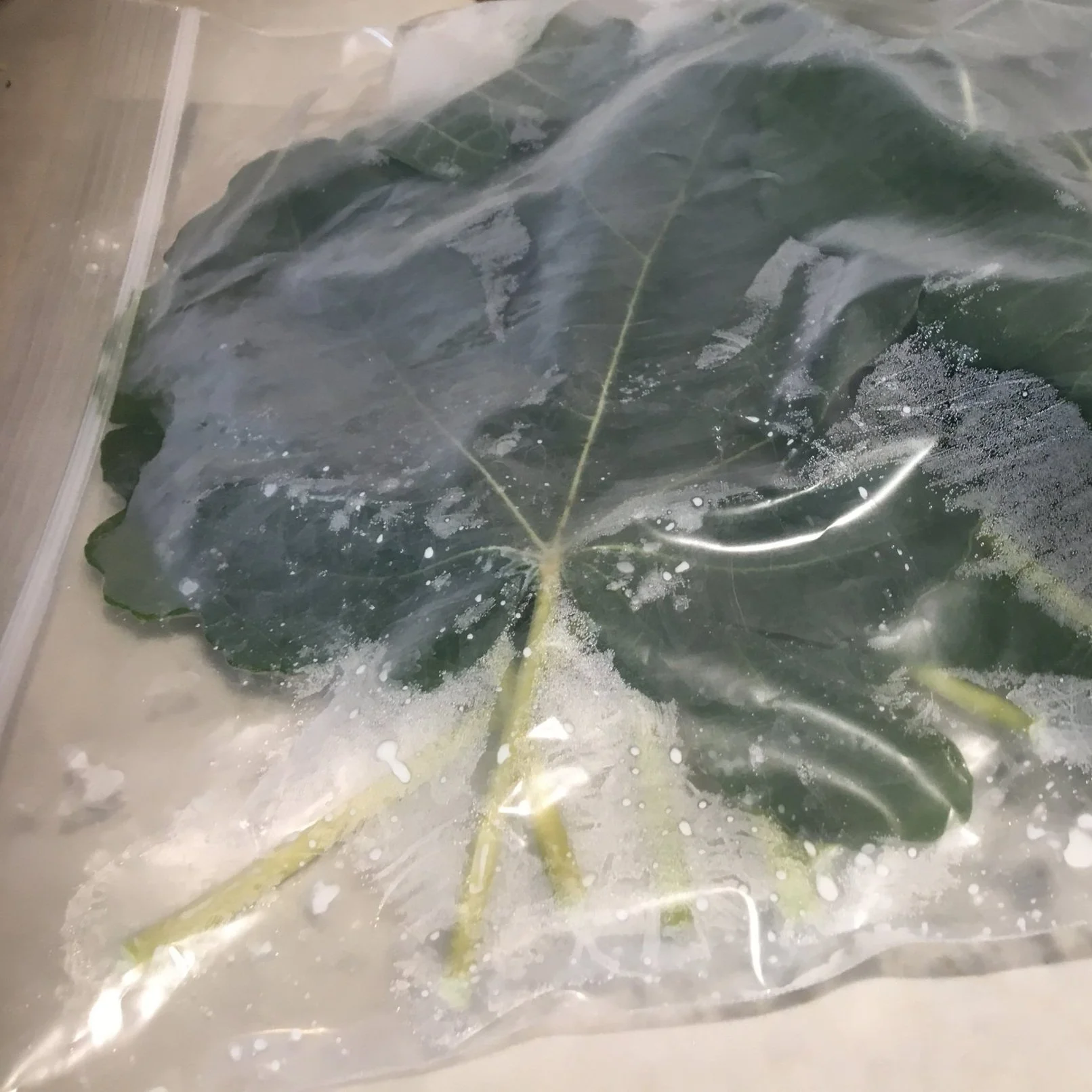

When freezing fig leaves, I put them in a stack and then slide that into a resealable freezer bag.

Time is the key to pulling out flavour from the fig leaves. That usually means soaking leaves for a day or two in cream (fat soaks up the flavour).

But if you want to get out the flavour more quickly, use frozen fig leaves. I discovered this when I froze fig leaves for use over the winter. Freezing breaks down the leaf, so the flavour releases much more quickly.

When freezing fig leaves, I put them in a stack and then slide that into a resealable freezer bag. This way it’s easy to remove a few at a time.

Serving ideas for Panna Cotta

Ramekins are a common way to serve puddings, custards, and panna cotta.

I’ve also served fig-leaf panna cotta in mason jars. And one time I used some of the tea cups that my wife Shelley treasures, tea cups that were her grandmother’s. We don’t serve high tea…so it’s nice to be able to use them for something.

This is an easy-to-make fig-leaf panna cotta recipe.

Ramekins are a common way to serve puddings, custards, and panna cotta. I’ve also served fig-leaf panna cotta in mason jars.

Top Tip for Panna Cotta

Give yourself at least 6 hours for the gelatine to set. If you’re serving panna cotta for supper, make it first thing in the day – or, even better, the day before.

Once it’s made, cover and refrigerate until you serve it.

FAQ Fig-Leaf Recipes

Can you make fig-leaf panna cotta without sugar?

I like the sweetness…so I’m not sure why you’d do that. But if you’re on a low-sugar diet, consider a sugar substitute for sweetness. I once had guests on reduced-sugar diets, so I used no-sugar, low-calorie monk-fruit sweetener and it turned out fine.

What about fig leaf custard?

Yes, you can make custard with a fig-leaf flavour too. Just steep the fig leaves in the milk or cream for a day or two as you would with fig leaf panna cotta.

Fig Leaf Panna Cotta Recipe

I use frozen fig leaves for this recipe because it’s faster. That way I don’t have a big bowl of cream with fig leaves cluttering up my fridge for a couple of days.

Ingredients

8 fig leaves, frozen beforehand

6 cups of heavy cream or whipping cream

2 cups whole milk

2/3 cup granulated sugar

¼ tsp. salt

2 tbsp. unflavoured gelatine powder

Directions

Soak frozen fig leaves in cream for 2-3 hours (or, if using fresh fig leaves, for 1-2 days – refrigerated)

Remove fig leaves and discard (they’re for the flavour…you don’t eat them)

In a small bowl or cup, sprinkle gelatine over 1 cup of milk and stir to dissolve the gelatine

Put cream, salt, sugar, and the other cup of milk into a saucepan

Heat the saucepan on low until steaming (I never rush heating milk or cream because I’ve burnt them too many times…)

Remove saucepan from heat and stir in the milk-gelatine mixture

Pour into ramekins and refrigerate, covered, until set (usually 4-6 hours)

Hear Chef David Salt Talk About Fig Leaves

Looking for More Garden-to-Table Cooking Ideas?

More on How to Grow Figs

More Fig Articles

Head back to the fig home page to search for fig articles by topic.

Fig Books

Fig Course

Fig Masterclass

The self-paced online fig masterclass gives you everything you need to know to grow and harvest your own figs in a cold climate!

(We also run it live once a year. If you’re interested in knowing when we next run the live online fig “camp” I’ll announce it in my newsletter. Hop on the newsletter list here.)

Vegetable Seed Guide: When to Start Seeds Indoors

Find out when to start vegetable seeds indoors.

By Steven Biggs

When to Plant Vegetables

Not sure when to start planting seeds indoors?

If you time planting well, your seedlings will be big enough to survive transplanting into the garden.

But don’t start seeds indoors too early: Earlier planting and bigger seedlings is not always better.

That’s because a seedling that’s stuck in a pot for too long, waiting to go into the garden, gets stressed. And sometimes stressed transplants don’t bounce back, even once you plant them into the garden.

(Late in the planting season big box stores often have discounted transplants: wilted, root-bound cauliflower, cucumber, and chard that have simply run out of steam…don’t be tempted!)

If you’re wondering when to start seedlings indoors, keep reading. This guide tells you when to sow seeds—and how to know when to sow seeds.

Why Start Seedlings Indoors

Start seedlings indoors to get a jump start on the season and to protect them from weather and pests.

There are two main reasons to start seeds indoors.

In cold climates, season length limits harvests—and starting seeds indoors give a longer window of growth for the crop

Indoors, we can control conditions and prevent pest damage, giving small seedlings a chance to get started at a suitable temperature, without getting mown down by bugs

When to Start Seeds Indoors

Luckily, vegetable seeds don’t all have to be planted at the same time. You can spread out seed sowing from mid winter through spring—when you start sowing some seeds directly in the garden.

The guidepost for choosing when to start planting seeds indoors is something called the average last frost date—or simply “last frost date.” This is the average date of the last spring frost in your area. (It’s an average, so some years there is a frost following this date.)

If you don’t know your average last frost date, a good place to start is by asking local gardeners, or checking with local seed vendors.

Work Backwards from the Average Last Frost Date

Pin this post!

Once you have your last frost date, you just work backwards to get the sowing date for all of your different vegetable seeds.

It’s your guidepost.

Workback: When to Plant Vegetables

Below is how many weeks before the last frost date I sow my vegetable seeds.

Keep in mind that none of this is cast in stone. You have a window of time for seed sowing. It doesn’t have to happen in one specific week.

That means that if you miss the mark with your celery seeds, and forget to sow them at 10 weeks, don’t sweat it. Sow them at 9 weeks, and your celery transplants might just be a bit smaller when you put them into the garden.

This list is a work in progress. If you have a favourite vegetable crop that’s not on here, e-mail me.

10 Weeks Before Last Spring Frost

Leek seed are some of the first seeds that I plant indoors, 10 weeks before the last frost date in the spring.

Indoors

These are the first vegetable seeds that I start indoors, under lights.

celery, eggplant, leek, onion, pepper, parsley

8 Weeks Before Last Spring Frost

Indoors

tomato

7 Weeks Before Last Spring Frost

Indoors

more tomatoes (we like our tomatoes here in the Biggs household!)

6 Weeks Before Last Spring Frost

Indoors

lettuce, cabbage family (broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, kohlrabi, kale)

Direct-Seed in the Garden

Direct-seeding carrot seeds in the garden 6 weeks before the last frost date.

This is also when I start to direct-seed some cold-tolerant vegetable crops in the garden. These include:

broad bean, carrot, pea, spinach, lettuce, turnip, dill, parsley

Plant or Transplant in the Garden

plant onion sets (small, pre-grown onion bulbs), and transplant onion seedlings

4 Weeks Before Last Spring Frost

Indoors

melon, basil, cucumber, squash, pumpkin

Direct-Seed in the Garden

radish, beet, chard, more lettuce

Plant or Transplant in the Garden

cabbage family seedlings

seed potatoes

2 Weeks Before Last Spring Frost

Direct-Seed in the Garden

corn, cheater beans*

*With beans, we usually wait until the soil is warm and there’s no further risk of frost. That’s because bean seeds can rot in cold, wet soil—and if young bean plants get hit by frost, they’ll die. But some years are warmer than others, and if it seems warm, I like to cheat and get in an early row of “cheater beans.” If they do well, I get beans sooner. (If they get nipped by frost, no big loss; I’ll just replant.)

Plant or Transplant in the Garden

lettuce

gladiolus bulbs (I know…they’re not a veggie, but I like to grow this cut flower in my veggie garden, reminds me of Grandma Q)

The Week of the Last Spring Frost

Wait until 1-2 weeks after the last frost date before transplanting pepper seedlings into the garden. They HATE the cold!

Direct-Seed in the Garden

beans, cauliflower, cucumber, squash

Transplant in the Garden

tomato (some people plant tomatoes a week or two after the last frost date…I’m impatient, so I plant them, but protect them as needed)

1-2 Weeks Following the Last Spring Frost

Direct-Seed in the Garden

Now it’s time to direct seed the cold-hating crops!

lima bean, edamame, melon, basil

Plant or Transplant in the Garden

Make sure the temperature will be over 10°C at night

celery, melon, pepper, eggplant

sweet potato slips

There are some crops that I start indoors, and also sow directly in the garden later. These cucumbers are sown directly in the garden.

You might notice that some crops, such as melon and basil, are in my list above twice: seeded indoors, and then directly sown outdoors. That’s because you can do it both ways, and having the same crop in two stages of development can give you a longer harvest window.

Make Successive Plantings

Don’t forget that after the initial planting of many of these crops, you can make successive plantings so that you have an ongoing harvest. That means after your first sowing of beet seeds, make more, at two-week intervals. Same with carrots, and leafy greens.

How to Stay Organized

If you’ve looked at my planting dates above, you might be wondering if there’s a simple way to stay organized.

There is!

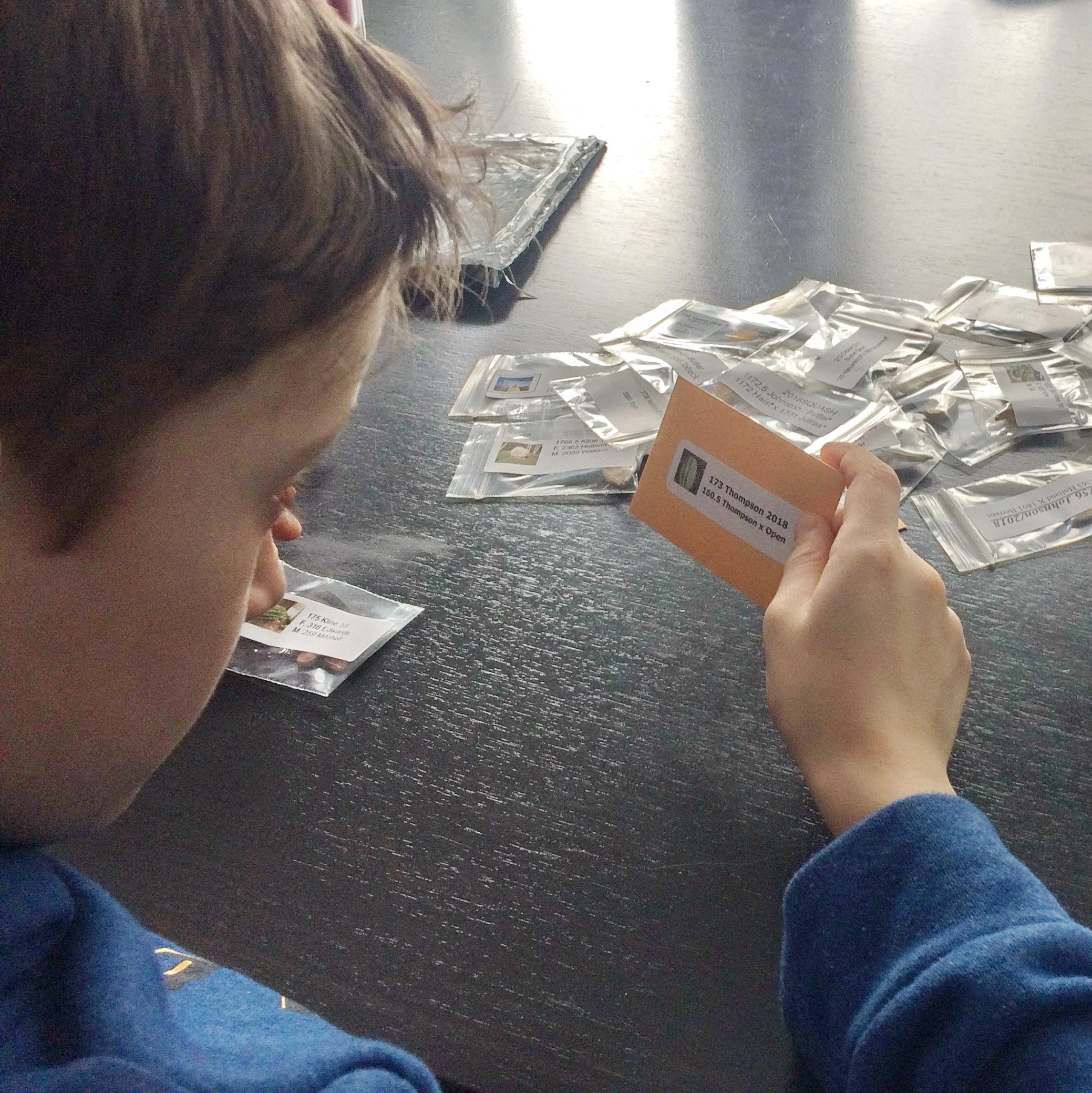

I sort my seed packets by starting date. I’m a visual person—so no spreadsheets for me!

Seed packets organized by planting date, so that I don’t forget to plant anything!

I simply make stacks of seed packets, organized by when they should be planted. Then, I mark my calendar for the various seed-starting dates—flagging 10 weeks, 8 weeks, 6 weeks, etc.

When the given week rolls around, I grab the seed packets for that week.

More on Vegetable Seeds

More on Growing Vegetables

Vegetable Gardening Articles

Vegetable Gardening Courses

Nursery List: Fruiting Shrubs, Unusual Fruit, and Hardy Fruit Trees

Where to find fruit trees for sale.

By Steven Biggs

Buying Fruit Trees, Fruiting Shrubs, and Berry Bushes

I get a lot of messages from people wondering where to buy fruiting plants. So I hope this list helps you find a nursery with the fruit trees you’re looking for.

This list focuses on nurseries, garden centres, and fruit-growing specialists in Canada and the northern USA.

It’s a work in progress. If there’s a nursery you recommend, please e-mail me to let me know.

Before you browse nurseries, get started with Tips When Shopping, below.

Tips When Plant Shopping

Here are tips to keep in mind as you get ready to order trees and shrubs.

Delivery vs. Pick-Up

It’s expensive to ship trees and shrubs! They’re big. And if there’s soil—they’re heavy too.

Delivery costs depend on the distance, the size of the plant, and whether it’s in a pot with soil, or is “bare root.”

(Bare root means it’s dormant, and there’s no soil.)

If picking up your fruit plants is an option, you can usually save quite a bit of money.

Ordering and Shipping Fruit Trees and shrubs

Shipping usually begins in spring, when there’s no further risk to the plants from cold temperatures.

The first to ship are “bare root” plants—dormant shrubs and trees with no soil. (Roots are wrapped in something damp to prevent them from drying out.)

Cross-Border Shipments

Some sellers don’t ship out of country. That’s because it usually involves “phytosanitary” inspections and paperwork.

Or, there might be restrictions on shipping some types of fruit to some regions (to avoid the spread of pests or diseases.)

If you find an out-of-country vendor who ships to your country, ask about the cost of phytosanitary certificates—as well as the delay that inspections can cause for your shipment.

When You Receive Your Order

Bare-root Plants. Keep them somewhere cool and dark until you’re ready to plant them, so that they remain dormant. Plant as soon as possible. Make sure the roots stay moist.

Potted Plants. There’s less of a rush planting potted plants than there is with bare-root plants. Keep plants well-watered until they’re planted.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Canada Nurseries

Bambooplants.ca

Ontario

Great selection of minor and unusual fruit plants.

Boughen Nurseries

Nipawin, Saskatchewan

Boughen sells fruit trees and berries for cold climates. This is where I found my favourite culinary crabapple, ‘Dolgo.’ They also have Nanking cherry, which, despite being easy to grow, can be difficult to find in many parts of Canada.

Corn Hill Nursery

King’s Country, New Brunswick

Owner Bob Osborne is a CBC radio columnist, and the author of the book Hardy Apples: Growing Apples in Cold Climates.

Hear Bob tell us about hardy apples on The Food Garden Life Show.

DNA Gardens

Elnora, Alberta

Specializing in hardy fruit trees.

Exotic Fruit Nursery

Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Hardy fruit, exotic fruit, and nuts.

Fruit Trees and More

North Saanich, British Columbia

A nursery and experimental orchard. Well worth a visit if you’re in the area—but they do mail-order too. Lots of less common fruit such as medlar and Asian pear. (And olives, citrus, and figs!)

Grimo Nut Nursery

Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario

A specialty nut nursery that also has uncommon fruit such as American persimmon and a number of mulberries.

Linda Grimo shares tips on how they prune mulberries in this guide to growing mulberries.

Hardy Fruit Tree Nursery

Rawdon, Quebec

Some good articles about growing fruit trees on the website. Grafting onto full-sized rootstock.

Nutcracker Nursery

Maskinongé, Quebec

I’ve ordered plums and damsons here and was pleased with the quality of the plants.

Pépeinière Ancestrale

St-Julien, Quebec

This is where I got my first cherry-plum bushes! Fruit trees and nut trees.

Prairie Hardy Nursery

Two Hills, Alberta

Recommended to me by my horticultural colleague in Alberta Donna Balzer.

Production Lareault inc.

Lavaltrie, Quebec

Berries and small fruit. (Also asparagus, rhubarb, and kiwi.)

Rhora's Nut Farm and Nursery

Wainfleet, Ontario

Specializing in nut trees, with some minor fruit too.

Riverbend Orchards

Portage la Prairie, Manitoba

Cold-hardy fruit bushes, including haskaps, currants, and cherries.

Silvercreek Nursery

Wellesley, Ontario

Some of my apple trees are from Silvercreek—and I took a fantastic grafting workshop there.

T&T Seeds

Headingley, Manitoba

Seeds, accessories, and fruit plants by mail order. Also a garden centre if you’re in the area.

TreeMobile

Toronto, Ontario

A not-for-profit organization supplying fruit trees and supplies to gardeners.

Hear our chat with TreeMobile founder Virginie Gysel.

Whiffletree Farm and Nursery

Elora, Ontario

Trees, small fruit, and orchard supplies.

Willow Creek Permaculture

Dutton, Ontario

Fruit and nut trees.

USA Nurseries

Pin this post!

Edible Landscaping

Afton, Virginia

Fruit trees, fruit bushes, berries, and exotics like citrus.

Honeyberry USA

Bagley, Minnesta

Cold-hardy fruit bushes including honeyberry, a.k.a. haskap.

Off the Beaten Path

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lots of figs, as well as other unusual fruit.

Hear the owner, Bill Lauris, talk about figs in this podcast episode.

One Green World

Portland, Oregon

We chatted with Sam Hubert from One Green World on the podcast to find out all about hardy citrus. They carry lots of other fruit trees, fruit bushes, and berries too.

Raintree Nursery

Morton, Washington

A diverse collections of edible plants including nut trees and nut bushes.

Trade Winds Fruit

Seeds for rare and unusual fruit.

More Sources for Plants

Here’s a Fig Nursery List to help you find fig trees for sale.

More on Growing Fruit

Head to the Growing Fruit Home Page for articles, interviews, and guides on how to grow fruit.

Grow Microgreens at Home for Easy-to-Grow Salad Greens all Year

How to grow microgreens indoors. The setup is simple. The materials are easy to get. There’s no need for fancy lights or equipment.

By Steven Biggs

Growing Microgreens at Home is Easy

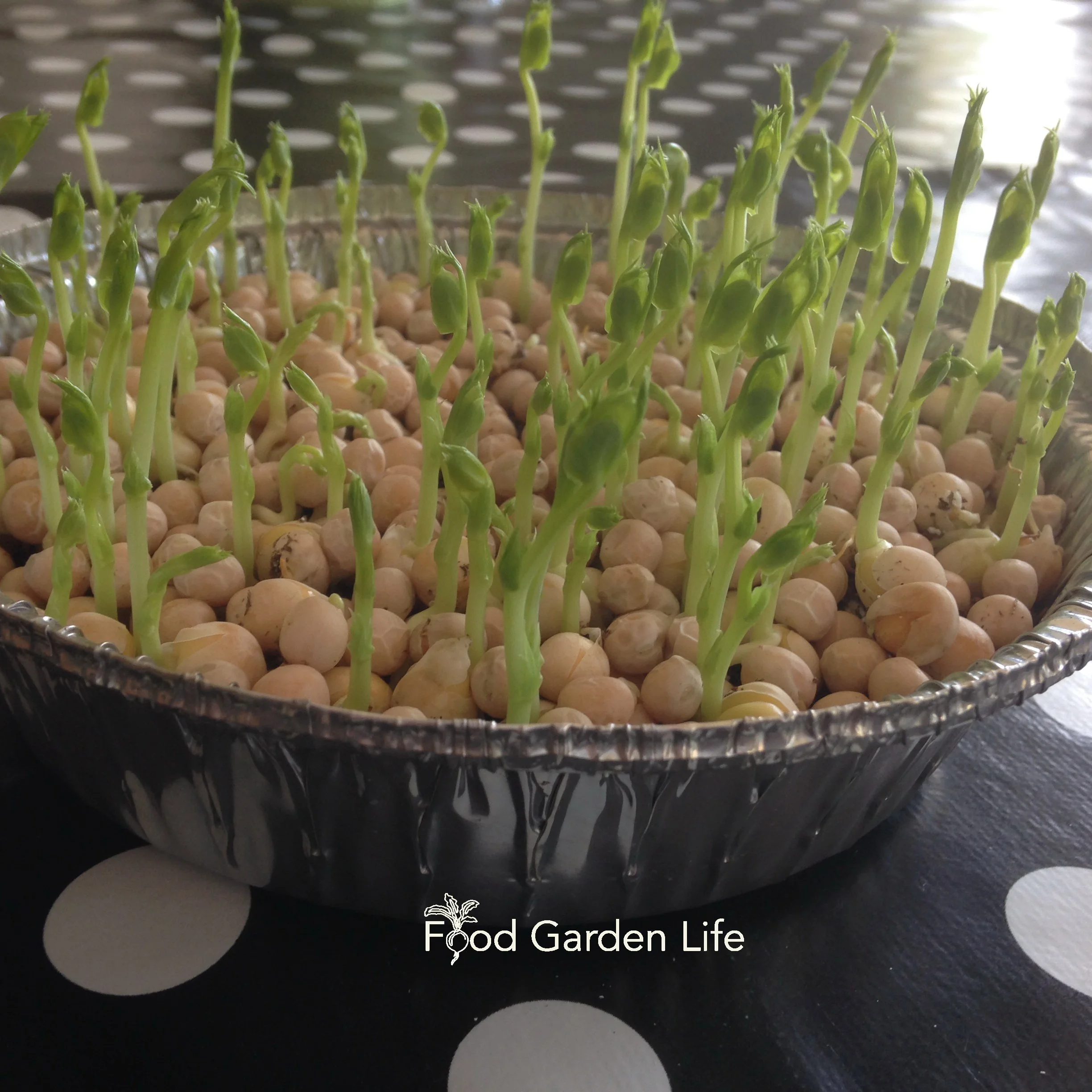

Pea shoots grown at home: All you need is a handful of dried peas, a pie plate, potting soil, and a windowsill.

On a recent trip to the grocery store I noticed small containers of pea microgreens. Gulp…a whopping $4.99.

The same amount of pea microgreens grown at home takes only a handful of dried peas, a pie plate, potting soil, and a windowsill.

Growing microgreens costs pennies—and it’s easy.

The setup is very simple. The materials are easy to get. There’s no need for fancy lights or equipment. And you can grow microgreens indoors any time of year.

Keep reading and I’ll tell you how to grow your own microgreens.

What are Microgreens?

Microgreens are immature plants. They’re often vegetable or herb plants. There are a few other fun ones, like sunflower and corn (deliciously sweet!)

They’re harvested while the plants are small and the stems still tender. Harvesting means cutting off the tops. Seems brutal, but it’s a short-term crop.

Why Grow Microgreens?

They’re easy to grow, quick to mature, and inexpensive: A perfect indoor crop for home gardeners.

I have a big garden, with lots to harvest into the fall and early winter. But microgreens are my go-to green crop for winter. When I want a green salad mid-winter, instead of lettuce or other leafy greens, I chop up microgreens.

If you’re already a microgreen connoisseur, another reason to grow microgreens at home is that you can grow microgreen crops you won’t find at the grocery store.

Grow microgreens with different tastes:

Spicy (e.g. radish)

Sweet (e.g. pea)

Bitter (e.g. lentil)

Nutty (e.g. sunflower)

A colourful tray of fresh microgreens.

And microgreens with different colours:

Light green

Dark green

Red

Purple

Crops for Home Microgreens

There are many different plants suited to a crop of microgreens, including vegetables, herbs, flowers—and others, like some common field crops!

Before you grow something into a microgreen, make sure it it’s edible. I’ve listed many microgreen crops below. If in doubt, see what seed vendors sell for microgreens.

Vegetable Seeds for Microgreens

Here are vegetables that are commonly grown as microgreens:

Grow microgreens from many different types of seed, giving you different tastes, textures, and colours.

amaranth, arugula, beet, broccoli, cabbage, carrot, chard, cress, dandelion, kale, kohlrabi, mizuna, mustard, onion, orach, pac choi, pea, radish, tatsoi, watercress

Herb Seeds for Microgreens

Here are herbs that are commonly grown as microgreens:

basil, cilantro, dill, fennel, lemon balm, parsley, shiso, sorrel

Flower Seeds for Microgreens

Here are flowers that are grown as microgreens:

borage, celosia, marigold, sunflower

Field Crop Seeds for Microgreens

Here are field crops that can be grown as microgreens:

alfalfa, barley, clover, chickpea, corn, lentil, quinoa, wheat

Microgreen Seed Mixes

There are also seed mixes with more than one type of microgreen seed, giving a blend of taste and colour.

My favourite is pea microgreens—a.k.a. pea shoots. They’re sweet, crunchy, and easy to grow. I also love sunflower microgreens for the delicious nutty flavour. (The husk of the sunflower seed is easy to remove as the sunflower microgreens get bigger.)

Buying Microgreen Seeds

Dried green peas from the grocery store.

When shopping for microgreen seeds you might come across the interchangeable terms “sprouting seeds” and “microgreens seeds.” It means the seeds are untreated and uncoated. They’re usually sold in a larger volume than seeds intended for the garden—so it’s better value. And in some cases, it means that the seed company tests the seed to be sure there’s no contamination with pathogens.

I use dried peas and lentils from the grocery store—the same dried whole peas used for cooking.

Stick with food grade seeds from the grocery store or seeds sold for microgreens.

Seed sold for planting in the garden is sometimes “treated,” which usually means with fungicides. Treated seed is not suitable for growing into microgreens.

First Microgreen Crop? Give Peas a Chance

First time growing microgreens? I like the peas-and-pie-plate approach. It’s easy!

I recommend pea microgreens (also known as pea shoots) as a first microgreen crop. Dried peas are easy to find at the grocery store, easy to grow, and have a sweet flavour—much like snow peas and snap peas.

It doesn’t matter whether you use green peas or yellow peas—the key thing is to use whole peas, not split peas…they won’t grow!

How to Grow Microgreens at Home

Choose a Location to Grow Microgreens

When you grow microgreens you’re using the energy saved up in the seed. The goal is a tender young stem and leaves that you cut off and eat as a green. That means you don’t need bright light. It doesn’t matter if the plants are gangly.

Supplies for Growing Microgreens Indoors

Here are supplies to grow microgreens at home:

Seed

Potting soil

Container

Spray botte (optional)

Soil for Microgreens

The potting soil is to hold moisture and let the microgreen plants anchor themselves as they grow. You don’t need to supply nutrients because the plants are using energy stored in the seeds. Start with fresh soil every time—don’t reuse soil.

Moisten the potting soil before planting.

Use a soilless potting soil. Coir or peat moss as a growing medium work well too.

Containers for Microgreens

There are lots of options for microgreens containers. You only need to have about an inch of potting soil, so any shallow container works.

Here are examples:

Lentil microgreens growing in a plastic container.

A standard 10”x20” plant tray

A pie plate

Takeout containers

Smaller containers dry out faster, so you’ll need to water more often.

If you trust your judgement with watering, don’t make drainage holes. But if you think you might overwater, punch a few holes in the bottom of your container.

Spray Bottles

A spray bottle for microgreens is optional. I don’t use one. Some gardeners use a spray bottle to avoid splashing around small seeds. Instead, you can water carefully with a gentle stream of water.

How to Plant Microgreens

Soak larger seeds such as pea, lentil, and sunflower overnight. (Soaking gives a faster, more uniform germination.)

Put an inch or two of potting soil in the container.

Put seeds on top of the soil, spacing them so that they’re close to each other, but not covering each other. Don’t cover seeds with soil.

Water so that the soil is moist but not wet. (You want the soil moist, not wet...don’t float your seeds!)

Place under lights or on a windowsill.

Pea Microgreens Step by Step

Top Tip: When seeds are in contact with the soil you get a faster, more uniform germination. Put something heavy over the microgreens after sowing. The weight pushes down on the seeds so that they are in contact with the soil. (I stack my pie plates full of seeds.)

Don’t do this: Don’t fertilize them. There’s enough stored energy in the seed to grow the microgreens until harvest.

Location for Microgreens

Growing microgreens under lights. Less light is OK too.

You don’t need perfect growing conditions, so make do with what you have. If you have a bright window or set of grow lights, these work well.

Low light is also OK too, because the plants are growing using energy stored in the seed. I’ve grown them on a dim countertop.

The warmer the temperature, the more quickly the microgreens grow.

Seeds sprout more quickly in warmer conditions. Here are ways to give your microgreen seeds more heat:

A heat mat

A sunny windowsill

The top of a hot-water radiator

A heated floor.

Growing Your Microgreen Crop

If you put something heavy on top of the seeds, remove it after a couple days. These amaranth microgreens were covered a bit too long…but they’ll bounce back.

Check daily to make sure the soil is moist and to see if your seeds are germinating.

If you put something heavy on top of the seeds, remove it after a couple days.

Harvesting Microgreens

Harvesting Pea Shoots

When I grow windowsill pea microgreens over the winter at room temperature, I expect to harvest them about 2 weeks after sowing.

Harvest microgreens when they get 3-4 inches tall, a size when they are tender and not fibrous.

The first cut is the largest. There might be a couple more smaller harvests with pea shoots. (Not all microgreens regrow from what remains after harvest.)

Spotty germination in this container of pea microgreens because the potting soil got too dry.

When the energy in the seeds is used up and they no longer send up new growth, compost them.

Harvesting Other Microgreens