How to Grow Currants - A Great Fruit for a Home Garden

How to grow currants

By Steven Biggs

A Neglected Currant Bush

Red currants are easy to grow, making them well suited to home gardens.

A lonely red currant bush under the apple tree next door showed me currants are a perfect fruit for home gardens.

That forlorn currant bush had been untended for years, growing in shade and heavy clay soil.

It had a lot going against it. Yet it reliably grew currants every year…and when they went unpicked, I reached through the fence to harvest them.

Why Grow Currants?

Currants are a great fit for home gardens for a few reasons:

They are easy to grow

They tolerate the less-than-perfect conditions of a home garden

They produce fruit even when neglected

They are versatile in the kitchen (syrups, jellies, cordials, compotes)

The fruit is rarely sold at stores (and expensive if you find it)

Despite all of these reasons to grow currants, they are less common here in North America than in Europe, where they are a garden staple. Keep reading to find out how to grow this versatile fruit in a garden, edible landscape, or food forest.

Currant Fruit

Black currants, red currants, and clove currants are all different species. There are some differences in pruning, but they’re all simple to grow and can be planted together.

Black currants have an intense flavour…people usually love them or hate them!

Black currant fruit can get up to 1 cm across. They have an intense flavour that I’ve heard variously described as piney, resinous, musky—and scrumptious. With black currants, it’s usually a love or hate relationship, there’s no in between.

Red currant fruit (and I’m lumping in pink and white currants here) tend to be a bit smaller than black currants, with fruit that get up to about 0.5 cm across.

Clove currants taste like a mild black currant. These are also known as buffalo or golden currant, and are often grown as an ornamental plant. (Also known as Missouri currant.)

How to Use Currants

They are similar in size and shape to blueberries. But while blueberries are often eaten fresh, currants are often made into jelly and juice because of the seeds and tartness.

The seeds are edible (I know a gardener who make black currant oil from the seeds). But the seeds are also the right size to get stuck in teeth and partial plates.

(One year I made a mixed fruit jam with currants, raspberries, and blueberries. After I gave my Uncle Bill a jar he teased me about my partial-plate-buster jam. These days I strain out the seeds when using them in jams.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Forget Store-Bought Pectin

Currants contain lots of pectin. Use them as a source of pectin when making jams and jellies from fruits that contain less pectin. My favourite combo is a raspberry-red-currant jam.

How Currants Grow

Red currant bushes in flower

Currants are multi-stemmed shrubs that can grow 1 - 2 metres high and wide, depending on the type and variety.

Red and black currants have clusters of green, frilly flowers. Clove currants have fragrant yellow flowers. The clusters turn into “strigs,” which are thin stems that carry a chain of fruit.

Red currants make flowers on “spurs” on older branches; while black currants make flowers on young wood.

Self-Fruitful

The flowers are “self-fruitful,” which means that you don’t need more than one variety for pollination and fruit production. Some sources recommend having two black currant varieties for better pollination, but if space is an issue, don’t sweat it: I’ve had gardens with a single black currant that performed well.

Immature currants look like little green peas. They can be beautiful as they ripen. Especially the red currants, which have long strigs laden with over a dozen fruit. They look like colourful jewellery on the bushes.

If you can’t tell apart your black and red currant plants, pick a leaf and crush it. You will have no doubt which plant is your black currant because of the distinctive smell of black currant leaves.

Currants in Garden Design

Currants are a great fit for a home gardens because you can weave them into your landscape.

Clove currant flowers

In designing edible home landscapes, many gardeners have trouble coming up with ideas for the shady north side of a building. Look no further. Currants are your answer.

Here are ideas:

Because they are well-behaved shrubs that don’t grow too tall or spread excessively, they are well suited to planting as a hedge around a vegetable garden

Red currants have branches that live for a number of years, making them a candidate for espalier

A well-behaved currant bush can be nestled right into an existing flower bed

Plant amongst taller trees, adding another layer of fruit-bearing plants to your garden

How to Plant Currants

The best time to plant or transplant currants is in the fall. That’s because they leaf out very early in the spring. If planting in spring, the earlier the better. Like any shrub, if you move it while dormant there is less stress to the plant.

Container-grown currant plants can be planted throughout the summer, but spring and fall are the best times.

Here are spacing guidelines:

In a row or hedge, aim for a spacing between plants of 0.5 – 1.5 metres, with rows 2 – 2.5 metres apart

For individual plants, plan for a clear area of up to 1.5 metres around the plant

Where to Grow Currants

Currants do great in climates where summers are moist and not too hot. Plant-hardiness zones are never an exact science, and hardiness varies with variety and site. But in general, currants are hardy in USDA zones 3-7.

Plant currants amongst taller trees, adding another layer of fruit-bearing plants to your garden

Gardeners in warmer zones can sometimes extend the range by growing in shadier areas where there is less heat stress.

In cold, borderline zones, a north-facing slope slows down growth in spring, making it less likely flowers will be hit by a late cold snaps. Mulching also keeps soil cooler and delays spring growth.

Soil for Currants

Currants tolerate a wide range of soils. Whatever the soil, amend with lots of organic matter to improve drainage, aeration, and moisture retention. This is important because currants have shallow roots.

Ideal: a moist clay soil with lots organic matter

The least ideal: a dry sandy soil

Pruning Currants

With regular pruning it’s possible to coax more fruit from a currant bush. However, as I explained earlier, in a laid-back gardener’s garden, they still fruit respectably well.

Here’s the key thing to know when pruning: Black currants grow differently from red currants (and white and pink). That means that you prune your black currants differently than red, white, and pink ones.

Red Currant Pruning (pink, white)

Red currant bushes have branches that produce fruit for a number of years, so you create a more permanent framework

Red Currants produce most heavily on three- and four-year-old branches

Aim for four to six stems each of one-, two-, and three-year-old wood

Gradually trim out stems after 4 years (unless you’re doing espalier…in which case you might keep them longer)

A healthy shrub sends up a number of new branches each year; prune out all but the best half dozen or so

*Note: If you read European texts, they often talk about red currants grown on “legs,” which means that there is a single stem coming out of the ground, and all the branches start to come out of that single stem a few inches above the ground level. It looks as if the plant is on a little leg. (I have never seen red currants growing on legs in garden centres here in Ontario, so if you have read about “legs” but can’t find bushes grown in this way, don’t sweat it.) The advantage, if you choose to propagate your own red currants on legs, is that the fruit branches are higher off the ground, and your fruit is less likely to get muddy. Black currants are not suited to legs because, as you’ll read below, their manner of growth is different.

Black Currant Pruning

Pin this post!

Black currant shrubs fruit most heavily on one-year-old wood, meaning that instead of creating a permanent framework as you do with red currants, you want lots of new growth. Prune to fully renew the bush over three years

Remove about a third of the bush each year

Remove any branches older than 3 years

Keep strong one-year-old shoots, and two- and three-year shoots with lots of one-year-old branches coming off of them

Keep 10-12 shoots per mature bush—aim for half of them being one year old

Plant new black currant bushes slightly deeper than they were planted before, to encourage more branches from below ground level

*Note: you might see the term “stooled” bush used to describe the best way to grow a black currant. This means that there are many stems coming from ground level, as opposed to a leg.

Many growers prune currants in late winter, while dormant. However, my preference is to prune soon after harvest. It’s when I have the time to do it.

Other Currant Bush Care

Mulch the soil below currant bushes with a couple of inches of straw, wood chips, composted leaves, or grass clippings. This does three things:

It keeps the soil moist

It helps to prevent fruit on lower branches from getting muddy

It prevents the growth of weeds

FAQ Growing Currants

What about white pine blister rust?

Currants are an “alternate host” for the disease white pine blister rust. Alternate host means that the disease requires more than one type of plant to complete its life cycle.

In the case of white pine blister rust, white pine trees, an important commercial species—can be killed by the disease. Currants infected with the disease may drop some leaves, but it doesn’t have a big impact on currant yield.

But the currants permit the disease to complete its life cycle—it can’t move from pine to pine.

Some things to consider when thinking about currants and white pine blister rust:

Are there white pines growing nearby? If you’re concerned about the disease, don’t plant currants within 300 m (1,000' feet) of white pines.

Are there wild currants and gooseberries in the area? (Wild currants and gooseberries are widespread, and are also alternate hosts for the disease.)

There are disease-resistant varieties of black currant (e.g. Titania, Consort)

Black currants are more susceptible to the disease than red and white currants.

Is it legal to grow currants?

Federal legislation in the USA made it illegal to grow currants until 1966. When the federal rules changed, many states continued to ban growing currants.

It is now legal to grow currants in many American states—but check to make sure that they’re permitted in your state. It’s not legal to grow currants in all states.

It is legal to grow currants in Canada.

What can I do about birds eating my currants?

Some people net bushes, though I find it’s too much work. If the birds are taking more than their fair share, pick before they’re perfectly ripe. They’re still perfectly good for your cordial, jellies, and sauces.

Where can I buy a currant bush?

Check out our list of nurseries that sell fruit trees and bushes.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Want More Fruit Ideas?

Articles: Grow Fruit

Visit the Grow Fruit home page for more articles about growing fruit.

Here are a few popular articles:

Courses

Here are self-paced online courses to help you grow fruit in your home garden.

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Fresh Tomatoes in March

By Steven Biggs

Keeper Tomatoes Last all Winter

IT’S MARCH. Last week I used up the last of my fresh tomatoes—tomatoes that I picked last October, just before the first fall frost.

The “keeper” tomatoes have been sitting on a tray in my basement storage room all winter, hence the name.

What They’re Not

Let’s be clear: this is NOT a thin-skinned, juicy tomato. It’s a thick-skinned, “keeper” tomato.

I once gave plants to my neighbours Joe and Gina. They hated them. They loved juicy tomatoes for sandwiches and meaty tomatoes for sauces.

What They’re Good For

Keeper, or “winter,” tomatoes are perfect for chopping up to use on salads and in cooking.

My favourite way to use them is in bruschetta.

Tomatoes in March. Grow a “keeper” or “winter” tomato.

My Favourite Keeper Variety

The variety I grow came from my Dad’s friend Dino years ago. Dino simply called it a “winter tomato.” So I just call it Dino’s Winter Tomato.

When it’s ripe, the skin has an orange colour; and when you cut into it, the flesh has a light red colour.

There are other keeper varieties around:

My neighbour Natalie gave me a larger keeper variety a couple of years back — and it seems promising.

Prairie Garden Seeds sells one called Clare’s Tomato

No Need to Start Early

Because I harvest my keeper tomatoes at the very end of the season, there is no point to starting them too early.

The fruit can’t compete when there are tenderer, juicy tomatoes around.

So I don’t rush to seed them in the spring. I start most tomatoes starting 8-10 weeks before the last frost. The winter tomatoes are the last ones I get around to…sometimes 6 weeks before the last frost.

Get tips to grow great tomato seedlings at home.

More on Tomatoes

This Cold-Tolerant Citrus Fruit is Super Fragrant: Yuzu

Yuzu: This Citrus is a Rare and Fragrant Foodie’s Delight (And You Can Grow it in a Cold Climate!)

By Steven Biggs

Grow Your Own Fresh Yuzu Citrus

Yuzu fruit, also called yuzu citrus, is very cold tolerant.

This citrus fruit looks similar to a mandarin orange. But scratch the rind and you’ll quickly know it’s not.

Don’t pop it in your mouth, either. This isn’t a peel-and-eat fruit.

Unlike a mandarin it’s:

Pucker-up sour

Super seedy

Delightfully aromatic

Chefs and food enthusiasts know all about yuzu. Yuzu juice and yuzu zest are prized.

But good luck finding fresh yuzu fruit for sale—or finding a yuzu plant at a garden centre. The gardening world hasn’t caught up with the culinary world when it comes to yuzu.

It’s too bad, because yuzu is easy to grow. And—for cold-climate gardeners—it’s even more cold tolerant than lemon.

With its fragrant flowers and glossy leaves, it’s a fine addition to the cold-climate kitchen garden. Grow it as a potted plant—or an in-ground plant in borderline zones.

Keep reading this article to find out how to grow and harvest your own yuzu in a cold climate.

What is Yuzu

Pin this post!

Yuzu (Citrus junos) is a very cold-tolerant citrus plant. The cold-tolerance is no surprise given its pedigree: It’s thought to be a naturally occurring hybrid of two other cold-tolerant citrus fruits, mandarin and ichang lemon.

Yuzu plants are fairly upright, making them easy to grow as a single-stem potted tree. I keep my potted yuzu at about 1.5 metres (5’) high.

When the fragrant white flowers come out in the spring, they’re a magnet for pollinators. Bees love them.

Unlike mandarin, yuzu peel is a bit pebbly.

Yuzu flowers are fragrant—and are a magnet for pollinators.

Like most citrus fruits, yuzu is evergreen, meaning it has leaves on it year round. (Unless you really stress it out, see below.)

Acid Citrus Fruits for Cold Climates

When it comes to growing citrus fruit in cold-climate gardens, here’s a great way to set yourself up for success: Start with “acid” citrus.

Acid citrus are the sour ones like lemon or lime—and yuzu

For sweet citrus, think navel oranges and grapefruit

Yuzu fruit is a bit pebbly, not smooth like a mandarin.

The reason to start with acid citrus fruit is that they can ripen in a cold-climate garden with cool or short summers. Sweet citrus need hot summers with sustained heat to ripen...and don’t always ripen.

Yuzu is an acid citrus. Perfect in colder climates.

Yuzu Tree Cold Hardiness

Yuzu Minimum Temperature

Yuzu fruit is an acid citrus, making it a good choice where summers are short or cool.

I’ve never pushed the lower temperature limits here in my Canadian Zone 6 (USDA Zone 5) garden because my yuzu tree spends the winter in a cold greenhouse, kept near freezing.

But yuzu can survive much colder temperatures than that.

Yuzu hardiness—like any plant hardiness—isn’t an exact thing. Hardiness guidelines vary, depending on who you ask. You’ll see recommendations down to -10°C (14°F) –and colder!

But one thing is for sure: As citrus go, yuzu is very cold-tolerant.

The reason for the varying minimum temperature recommendations is that hardiness is affected by a few things.

Here are a few things that affect the hardiness of a yuzu (or any plant!)

The rootstock used for grafted yuzu trees

Young trees are more tender than mature trees

New growth is affected by cold before older, woodier stems

The duration of cold temperatures

How sheltered or exposed the tree is

How many degrees the temperature drops

Container trees are more susceptible to cold than in-ground trees because the temperature around the roots fluctuates more

Yuzu Cold Tolerance: Bonus Point!

Covering everything from lemon varieties, to location and watering, to pruning and shaping, to overwintering, dealing with pests, and more—and including insights from fellow citrus enthusiasts—this book will give you the confidence you need to grow and harvest fresh lemons in cold climates.

Some citrus (e.g. lemon) bloom on an ongoing basis—so a plant can have unripe fruit going into winter. This can be fun if it’s indoors and you want to pick lemons over winter.

But the fruit can’t get as cold as trees; when the fruit freezes it spoils.

That means that the temperature at which the fruit freezes (around -2°C, 28°F) becomes the minimum winter temperature for cold-climate gardeners growing lemons outdoors.

Find out how cold lemon fruit can get over the winter.

Unlike lemon, yuzu has a spring bloom and fall ripening…so there is no fruit on the tree over the winter. That give you a wider temperature range for overwintering. You’re not constrained by the freezing temperature of the fruit.

How to Grow Yuzu

Grow Yuzu in a Pot

Yuzu does well as a potted plant. With its upright growth, it’s easy to manage.

Here are a couple of top tips for growing yuzu as a potted plant:

Use a potting soil that drains well

Keep the soil moist, but not wet

Potted Plant Yes: Houseplant No

Just because it grows well in a pot doesn’t not make it a good houseplant.

It’s not suited as a houseplant over the winter. Centrally heated homes are too warm. Instead, pick a bright and cool spot for winter. If you have a sunroom or a cool greenhouse, that’s perfect.

(I’ve also stored my yuzu in a cold, dark garage. The plant isn’t growing in cold weather—so it will tolerate the dark.)

No Place in Winter?

Not sure where to put a potted yuzu for the winter? A friend has a spare bedroom and turns off the heat there over the winter. It has a bright window, and is 10°C (50°F) cooler than the rest of the house. Perfect for citrus!

Outdoors for Summer

Wherever you store it for the winter, be sure to put it outdoors for the summer. Pest pressures are lower—and you have pollinators for the flowers.

Grow Yuzu in the Ground Outdoors

The first time I came across in-ground, unprotected yuzu trees growing here in Canada was when Bob Duncan gave me a tour of his experimental orchard on Vancouver Island. He has a great video about yuzu; watch it here.

Beyond USDA Zones 9-10, in borderline areas, choose a protected site with full sun and good drainage.

In borderline areas, you can grow yuzu flat (as an “espalier”) against a south-facing wall and protect it from winter extremes with horticultural fleece and a string of incandescent Christmas lights, as is done for lemons in borderline areas.

Another option in borderline areas is to grow yuzu in the ground in an unheated greenhouse.

As cold temperatures get close to the cold-hardiness limit—especially when coupled with cold wind—yuzu plants might drop their leaves. If the branches are still alive, they will grow new leaves in the spring. Scratch the bark to see if the cambium is still green…and if it is, you might be in luck.

Beware the Thorns

Whether it’s in the ground or a pot, mind the thorns! They are far from dainty! We’re talking horticultural acupuncture…

If you have yuzu on a patio where people might brush past it, snip off protruding thorns with your garden shears. If you have a larger tree and you’re reaching into it to harvest, thick gloves are a good idea.

Yuzu Tree Care

When a lot of fruit set, some small fruit drop off…but if they all drop off, the plant is stressed.

Potted yuzu plants need more care than in-ground ones. Like most fruit trees, when they’re stressed, they might drop fruit and leaves. A common stress with potted plants is drying out.

Here’s a good way to think of watering:

Don’t overwater and keep the soil continuously wet

Allow the soil to dry a bit before watering—let is get to the dry side of moist

When you water, water enough so that all of the soil in the pot is moistened and you have water coming out the bottom

Feeding

The top tip for feeding is to use a fertilizer that has “micronutrients.” Deficiencies of the micronutrients iron and zinc are common.

Pruning Yuzu Trees

Yuzu marmalade. It makes great marmalade on its own—or mixed with other citrus fruit. More yuzu cooking ideas below.

For starters, remove growth from below the graft line…it’s your rootstock sneaking up. Not sure where the graft is? Look for a bump on the main stem close to ground level. (More on grafting yuzu below.)

Next, tidy things up:

Remove dead branches,

Cut out damaged branches

Remove interior branches that don’t get a lot of light and have few leaves

Next:

Prune to allow air movement within the plant

Prune so branches are well spaced and fruit will get some light

Trim back branches that have grown too long

Next, let’s look at how to prune a young tree compared to how to prune a mature tree.

Keep Your Lemon Tree Through the Winter

And enjoy fresh homegrown lemons!

Shape Young Trees

With young trees, we’re pruning to develop the shape. We’re creating a permanent framework of branches.

If you have a single-stem young plant (a “whip”) you want to get it to branch out. This is done with a “heading” cut. It just means cutting off the top of the stem.

If it’s a grafted plant, first find the bump on the stem so you know where the graft is. Make your heading cut well above this.

As side branches form after the heading cut, pinch the tips once they have 3-4 sets of leaves, which will cause them to send out side branches. You’re causing a shorter branch with side branches.

A well-shaped tree has branches coming out from the main stem at different heights…a bit like a spiral staircase.

Pruning Older Trees

This book will help you apply creative “fig thinking” in your garden and harvest fresh figs even if you have a short summer or cold winters. With some fig thinking, you can harvest figs in areas where they don’t normally survive the winter! In this book, I share many of the questions I have been asked about growing figs in temperate climates, along with my responses.

With young trees we’re creating a framework of branches. With older trees, the focus is size control.

My yuzu is at its final size: I don’t want it to get any bigger. So every year, I prune it back to the permanent framework of branches.

Prune in spring, before there’s new growth. If you heavily prune an actively growing tree in summer, it can cause lots of new growth that is less likely to survive cold winter temperatures.

Where to Get a Yuzu Plant

Canadian garden centres often bring in citrus plants from California in the spring. Ask in good time to see if they’ll bring in yuzu.

Mail order from a specialist nursery that carries citrus. Many specialist nurseries take pre-orders, and then bring in a load of citrus in the spring.

Propagating Yuzu

Can you Grow Yuzu Plants from Seed?

Yuzu is easy to grow from seed.

But…

I hear from gardeners who seed-grow yuzu plants…and then wait and wait and wait. For years. I’ve seed-grown yuzu too…and I’ll report back in a few years when they fruit for me!

The reason for the wait is that seed-grown plants go through a juvenile stage. It can be years before they produce fruit.

Grafting and Budding

With grafting and budding, we’re putting bits of a mature yuzu plants onto a set of roots that has desirable traits (smaller plant size, early bloom and fruit, cold hardiness).

Because we’re using mature wood to graft and bud, the result is a plant can produce fruit more quickly than seed-grown plants.

Flying dragon (Poncirus trifoliata) is a common rootstocks that has good cold-hardiness and dwarfing properties.

Cuttings and Air Layering

Like many other citrus, you can also propagate yuzu from cuttings and air layering.

Yuzu Flowering and Pollination

A cool period over the winter months encourages flower bud formation.

Yuzu is self-pollinating, meaning you can get a crop if you have only one plant.

(It doesn’t mean you don’t need insect pollinators…so if the plant is indoors where there are no pollinators, be prepared to act the part yourself! Simply jostlie flowers with a cotton swab to move around pollen.)

Small fruit will already be forming from early flowers as the blossoms finish up.

Harvest Yuzu Fruit

Yuzu is often picked green, or as it just begins to change colour.

Ripening time depends on where you are and how soon your plant starts growing in the spring. My yuzu ripen in the fall.

Commercially, yuzu is often harvested green. (If this sounds strange, it’s the same thing with limes; they are picked green, even though they eventually ripen to yellow.)

In a home garden setting, you can experiment by picking at different stages of ripeness and seeing how the flavour evolves. Try picking all the way from green through to orange. As it gets very ripe, it feels puffy when you squeeze it—and at this point, it’s harder to zest and the fruit is no longer very juicy.

Yuzu Pests

In cold-climate gardens, pest problems are minimal.

Pests are more of a problem indoors—as with most plants.

A common indoor pest is spider mites. Because I overwinter my yuzu somewhere cold, I have no spider mite problems through the winter. But if the plant were somewhere warmer I’d expect spider mites. Insecticidal soap and horticultural oil are both useful for controlling spider mites.

Yuzu Recipes

The ingredients to make yuzu kosho paste: yuzu fruit, salt, hot peppers.

The fruit is versatile. It works well in savoury dishes and desserts. Try it in cocktails, marinades, and desserts.

And like other citrus, it contains lots of pectin, so you can make yuzu marmalade.

The yuzu taste is distinct. I find it very floral. The yuzu juice is tart, and the yuzu peel is full of aromatic oils. Use both.

You can also use it where you might normally use other citrus fruits.

Yuzu, honey, and cranberries to make cranberry sauce.

Here are a few ideas:

Yuzu kosho (citrus chili paste) – I love this in ramen

Salad dressings

Marinade

Instead of lemon in a spanakopita-style pastry

In cranberry sauce (instead of orange) – a big hit in my family

Marmalade

Yuzu tea

Top Tips for Growing Yuzu

Cool temperatures over winter is best

Don’t overwater in winter

Trim off thorns if it’s somewhere you walk past!

Yuzu FAQ

What is a yuzu lemon?

Savoury pastry: The ingredients to make a chard-and-yuzu spanakotpita-style pastry.

It’s another name for yuzu fruit. It’s also called yuzu citrus, Japanese citron, and Yuzu Ichandrin

Can yuzu grow in Canada?

You can grow it in the ground, unprotected in the mildest areas of Canada. In other areas, grow in the ground with protection—or as a container plant.

How long does it take to grow yuzu?

A grafted or budded tree (which is what trees at garden centres usually are) can produce fruit while still quite young.

Can yuzu be grown in pots?

Yes! For more insights into growing citrus in pots, read this article about how to grow a lemon tree in a pot.

Can yuzu be grown from seed?

Yuzu grows easily from seed. Don’t let the seeds dry out after removing them from the fruit. Place them in a pot with moist potting soil, and cover with some more potting soil—about the same thickness as the seed. Then keep it moist and be patient.

What is Sudachi?

Sudachi (Citrus sudachi) is another acid citrus with similar parentage to yuzu. Like yuzu, it is often harvested green. The fragrance is slightly different from yuzu. It is less seedy than yuzu.

Do people grow it commercially in cold climates.

Yes. There’a a greenhouse in Laval Quebec selling yuzu and sudachi. And here’s a story about yuzu in New Jersey. (I love the whole yuzu fruits filled with tasty treats!)

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More Citrusy Ideas

Here’s a Guide to Growing Meyer Lemon Trees.

How To Grow a Lemon Tree in a Pot

Book: How to Grow Lemons in Cold Climates

Covering everything from lemon varieties, to location and watering, to pruning and shaping, to overwintering, dealing with pests, and more—and including insights from fellow citrus enthusiasts—this book will give you the confidence you need to grow and harvest fresh lemons in cold climates.

Online Course: Grow Lemons in Cold Climates

New to growing citrus in cold climates? Or bitten by the lemon bug and want to up your game?

Lemon Masterclass equips you with information and creative ideas so that you can make the most of your cold-climate garden for growing lemons and other citrus.

Harvest from Your Hedge! Get These Edible Hedge Ideas

By Steven Biggs

Edible Hedge to Food-Forest Hedge

Find out how to grow an edible hedge.

Need more space in your garden? I’m always looking for ways to squeeze more food plants into my edible landscape. My “foodscape.”

I recently dotted my rows of currant and gooseberry bushes with plum trees. At the base of the rows are strawberry plants and mint. My edible hedge of currant and gooseberry bushes is becoming a “food forest hedge.”

The currants tolerate shade—so as the plum trees get bigger and shade them, the two can co-exist. The strawberry plants need some sun, and along the south-facing edge they get it. And the rapacious mint (which I never normally plant in the ground because it’s so aggressive) fills in shadier nooks.

If your challenge is space—if you have a list of fruit trees and bushes you want to grow, but can’t see how they’ll fit into your yard—an edible hedge might be the answer.

Keep reading because this article will give you ideas for creating an edible hedge suited to your space.

My Edible Hedge Inspiration was a Hedgerow

Wild plums growing in a hedgerow at my friend’s farm got me excited about the idea of an edible hedge and food-forest hedges.

When I was walking the edge of a field at my friend Anton’s farm one day, I came to a spot where the hedgerow was painted red by a heavy crop of fruit. Wild plums. I stood there grazing plums—and when I was full I went back to the farmhouse to get Anton.

We picked a bushel of plums and barely scratched the surface. They made excellent plum pie and plum jam.

I remember thinking that if fruit grows so prolifically on its own, the manicured approach of an orchard might not always be the best approach for a busy home gardener.

That experience also made me think of when I lived in the UK, in a rural area where small fields were separated by hedgerows. From those wild hedgerows I picked plums, blackberries, and raspberries.

(And come to think of it, my neighbour gave me a pheasant that he hunted from the hedgerows too! I made roast pheasant with a mulberry-Cointreau sauce.)

What is an Edible Hedge?

Cooking wild plums from the hedgerow.

Whenever I see a perfectly clipped cedar hedge boxing in a yard, I wonder what it would look like to instead have a perimeter of edible plants. An edible hedge.

An edible hedge is just a row of food-producing trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants:

It can be a row of a single type of plant, like my former currant hedge – or it can be a mixed and layered planting, sometimes called a “food-forest hedge”

It can be manicured – or it can look more natural, like that plum-laden hedgerow

The plants in your edible hedge can have different edible parts:

Fruit (e.g. plum, blueberry, elderberry)

Nuts (e.g. hazelnut)

Flowers (e.g. rose, elderberry, redbud)

Leaves (e.g. grape leaves)

What is a Food-Forest Hedge?

Pin this post!

With a food-forest hedge, we take the idea of an edible hedge and weave in ideas used in permaculture, giving a dense, mulit-layered planting.

Whichever approach you prefer, with a diverse planting you can get a staggered harvest. In a home garden we’re focusing on a hedge for year-long grazing. We’re not trying to replicate the way a commercial grower maximizes yield over a short period.

One other thing: The more diverse the mix of plants in your edible hedge, the better your “garden insurance.” If one plant flounders, another takes over.

Using Edible Hedges in an Edible Landscape

There are different ways you can weave an edible hedge into an edible landscape.

Backbone. Use the hedge as the backbone of your garden, the feature that leads you into your space. I’ve often seen deep yards with long perennial beds that serve this goal…why not an edible hedge?

Backdrop. Your edible hedge is at the perimeter of your space. It defines the space, gives you privacy—and gives you food.

Windbreak. In open areas where wind is a challenge, use your edible hedge as a windbreak.

Garden room. Use your edible hedge to separate part of your yard and create a separate garden room.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Remember the Rules…and Maybe Break Them

If what I’ve said so far sounds like blasphemy to you—if you’re picturing a tangled mess—here’s a bit more to think about:

Small-space gardens don’t have to follow the rules that orchardist follow or that textbooks prescribe. You can plant multiple fruit trees in one hole! Check out these ideas from Dave Wilson Nursery.

Permaculture orchardist Stefan Sobkowiak joined me on The Food Garden Life Show to talk about his orchard system of “trios” that mixes up different fruit tree species with nitrogen-fixing trees. You can tailor the same sort of “polyculture” to your yard. Tune in here to hear about his system.

Gardening is a great cure for perfectionism.

Edible Hedge Plants Ideas

Here are plant ideas for your edible hedge, edible food-forest, or hedgerow.

Barberry bush in the winter. The berries are edible.

Barberry

I love barberry for the red berries that last right into the winter. Beautiful—and edible. (Try dried barberry with rice.)

Blackberry and Raspberry

Raspberry canes sucker a lot, so be prepared for them to spread. My thornless blackberries are well behaved and don’t sucker. (But they do “tip layer.” Here’s more on tip layering.)

Some raspberry varieties fruit only in summer. Some also fruit in the fall. Take your pick.

Blueberry

Not something I grow here because my soil isn’t ideal, but a staple for edible hedges where it grows well.

Bush Cherries

There are a few different members of the cherry family that have a bush-like growth habit and can be a good fit for an edible hedge, edible landscape, food forest, or hedgerow.

Nanking Cherry

Dwarf Sour Cherry

Evan’s Cherry

There are also a couple of native cherries that grow as small trees or bushes—and you can prune them so that they have a bush form.

Pin cherry, a native cherry that works well in an edible hedge.

Chokecherry

Pin Cherry

Find out more about different cherries for your edible hedge.

Take a deep-dive into Nanking cherry.

Cherry Plum

The cherry plum (Prunus cerasifera) isn’t too common in the landscape trade—and that’s a pity. It’s extremely cold tolerant, had attractive spring bloom, edible fruit, and nice fall colour.

Chokeberry

The chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) is a native North American shrub that is often overlooked. It’s also simply called “aronia” sometimes. The fruit has pucker power, but mixed with other fruit in smoothies, or made into a syrup, it’s great.

Hear more about aronia in this chat with agronomist Laurie Brown.

Crabapple

Dolgo crabapples.

There’s crabapple…and then there’s crabapple! Some are small and horrid, so sour and astringent that you’ll regret tasting them.

But there are others that are so tasty you’ll go back for more. My favourite crabapple is ‘Dolgo,’ a variety known for its excellent culinary properties. (We make it into a beautiful red sauce—and into crabapple ice cream.)

Currants

I have a lot of good things to say about currants (Ribes sp.) for home gardeners in cold climates. They’re great for edible landscapes, edible hedges, food forests, and more! In a nutshell, they tolerate shade and poor soil, and still fruit well even when not pruned to perfection.

Find out how to grow a great crop of currants.

Hazel

The American hazelnut (Corylus americana) is a fast-growing shrub that’s very cold hardy. If it weren’t for the army of squirrels that marches on my garden as soon as anything emerges, I’d have lots of hazel.

Like currants, it does fine in poor soil.

(And one more idea for you: If you’ve ever thought of coppicing as a way to produce your own garden poles and stakes, hazel is a good candidate.)

Hardy Kiwi

Here’s an easy-to-grow, hardy fruit vine that can be a nice addition to an edible hedge.

Hear about hardy kiwi as we chat with agronomist Laurie Brown.

Rose

Rose petals are edible, and rose hips (the fruit) are good for teas, jellies, and liqueurs.

Whatever you do, don’t put a hybrid tea rose or a fussy floribunda rose in your edible hedge. Get a disease-resistant shrub rose.

Elderberry

Flowers on elderberry are edible too!

Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) has both edible fruit and flowers. We make elderflower champagne and elderberry syrup.

Elderberry tolerates partial shade and moist conditions. My first elderberry patch was from a wild plant I dug at a friend’s farm. But there are also improved varieties for larger fruit size and increaded yield.

Hear our chat about elderberry with agronomist Laurie Brown.

Grape

Probably not for those who want a more manicured look…but a grape vine can wend its way through a hedge until if finds space and light.

Remember, along with the fruit, young grape leaves are great for making dolmades (stuffed grape leaves.)

Looking for grape variety ideas but not sure where to start? Hear about “Canada’s Grape.”

Haskap

Haskap (Lonicera caerulea) is a very cold-hardy bush with fruit that looks like elongated blueberries.

They’re a great fit in a mixed planting such as an edible hedge because they’re the first fruit of the summer, usually ready at the same time as strawberries.

Hear our chat with Haskap breeder Bob Bors.

Highbush Cranberry

Highbush cranberry fruit.

Highbush cranberry (Viburnum trilobum) is a native North American plant that’s very cold-tolerant. It looks very nice too. There are flowers mid-summer, bright red berries for winter appeal, and you don’t harvest until after there’s been frost.

Like elderberry, it’s a good candidate for areas with more soil moisture.

(Highbush cranberry is not related to commercially produced cranberries.)

Hear foraging expert Robin Henderson talk about foraging highbush cranberry.

Plum

You have lots of choice when it comes to plums. There are wild plums, European plums, Japanese plums—and plum relatives such as damsons.

I planted damsons because I can’t find the fruit for sale anywhere…and I remember the damson-jam tarts my Nana made for me when I was a kid.

Quince

There’s the quince tree (Cydonia oblonga), and also the unrelated Japanese quince bush (Chaenomeles sp.). Both give fruit that’s too hard and acrid to eat when picked—but which can be cooked into marvellous delights.

Find out more about how to grow quince.

Sea Buckthorn

Sea buckthorn adds nice contrast to an edible hedge.

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) is a super tough, wind, heat, and drought-resistant plant that grows in poor soil.

The silvery leaves and orange berries make it a beautiful addition to an edible hedge (although I can’t say I’m in love with the taste…)

Hear agronomist Laurie Brown talk about sea buckthorn.

Serviceberry

With serviceberry, we’re talking about a family of related fruiting bushes and small trees. Also called Juneberry in the USA. Saskatoon berry is a member of this clan that’s grown commercially, and has many improved varieties.

Find out how to grow the Saskatoon berry (a.k.a. Juneberry).

You Don’t Have to Rule Out Tree Fruits

If you’re not worried about a manicured hedge clipped to a low height, remember that you can add in fruit trees too.

And you don’t even have to grow them as trees…as Dr. Ieuan Evans tells us, many of what we think of as tree fruits can grow as bushes too. Find out more about growing fruit trees as bushes.

Remember You Can Add Herbaceous Plants

Permaculture design encourages multiple layers, something you can incorporate into an edible hedge.

Read about perennial edible plants for edible landscapes.

Looking for More Ideas?

Looking for more food-hedge ideas? Hedgerows might give you inspiration.

How About an Alcoholic Hedge?

Hops as a hedgerow plant.

UK garden designer Matt Rees-Warren talks about hedgerows with food plants such as blackberry, sloe berry, hops, raspberry, and hazelnuts.

Wondering about sloe berries? They’re in the same family as plums—and are often used to make sloe gin. That’s why Rees-Warren says sometimes these hedgerows are called, “alcoholic hedges.”

Edible Hedges in Permaculture

Permaculture farmer Tim Southwell in Montana grows what he calls a “food hedge” (or “fedge”) on his permaculture farm. It provides privacy, blocks wind, attracts birds, and keeps livestock where they are supposed to be.

Find out more about Tim’s food hedge.

Edible Hedges Have Much in Common with Forest Gardens

Dani Baker is a forest-garden expert. A forest garden, like a food-forest hedge, is set up with layers of edible plants, designed to be a self-sustaining system once established.

Many of her ideas can be applied to an edible hedge. Hear about how to grow a home-scale forest garden.

Edible Hedge Hints and Tips

Pick plants for your garden hardiness zone.

Think of sunlight…but don’t be a perfectionist, because a hedge isn’t a perfect setting for a crop.

Mulch so that weeds don’t get the upper hand.

FAQ

How do I prune an edible hedge?

If you a growing an edible hedge with a number of different plants in it, forget having a manicured, uniform hedge.

Prune each of the different plants within the hedge to optimize fruit production. For example, elderberry fruits best on second-year branches—so when you get to your elderberry bushes, prune away many of the old branches to encourage new growth.

I said above to forget the notion of a manicured hedge, but that doesn’t mean you can’t pick a maximum height. You might want to cap the height so you can harvest without a ladder. (That’s what I do with my pawpaw trees, keeping them short enough to pick from the ground.)

But what about birds?

Depending on where you are, you might find that some of your edible crops are very attractive to birds. I know that my haskaps are ripe when I see robins darting into the bush!

My approach to birds is to pick fruit that they favour in good time. The longer it’s on the bush, the more they get. This doesn’t mean picking the fruit before it’s ripe—but not waiting long once it’s ripe. I don’t get as much as I would if I netted the bushes…but netting takes time.

What about plant spacing for edible hedges?

Spacing recommendations are often for commercial production. A hedge is different; we’re creating a dense, layered mix of plants. Don’t be afraid to play around with spacing.

What if my garden is shady?

If your garden is shady, you can’t grow everything I mentioned above. But you DO have options. Find out more about plants for shade.

More on Edible Landscaping

Need Help?

Get professional advice from horticulturist Steven Biggs.

Edible Gardening Course

Grow Olives in Cold Climates

Want to grow olives but live in a cold climate? This article tells you how you can grow and harvest your own olives.

By Steven Biggs

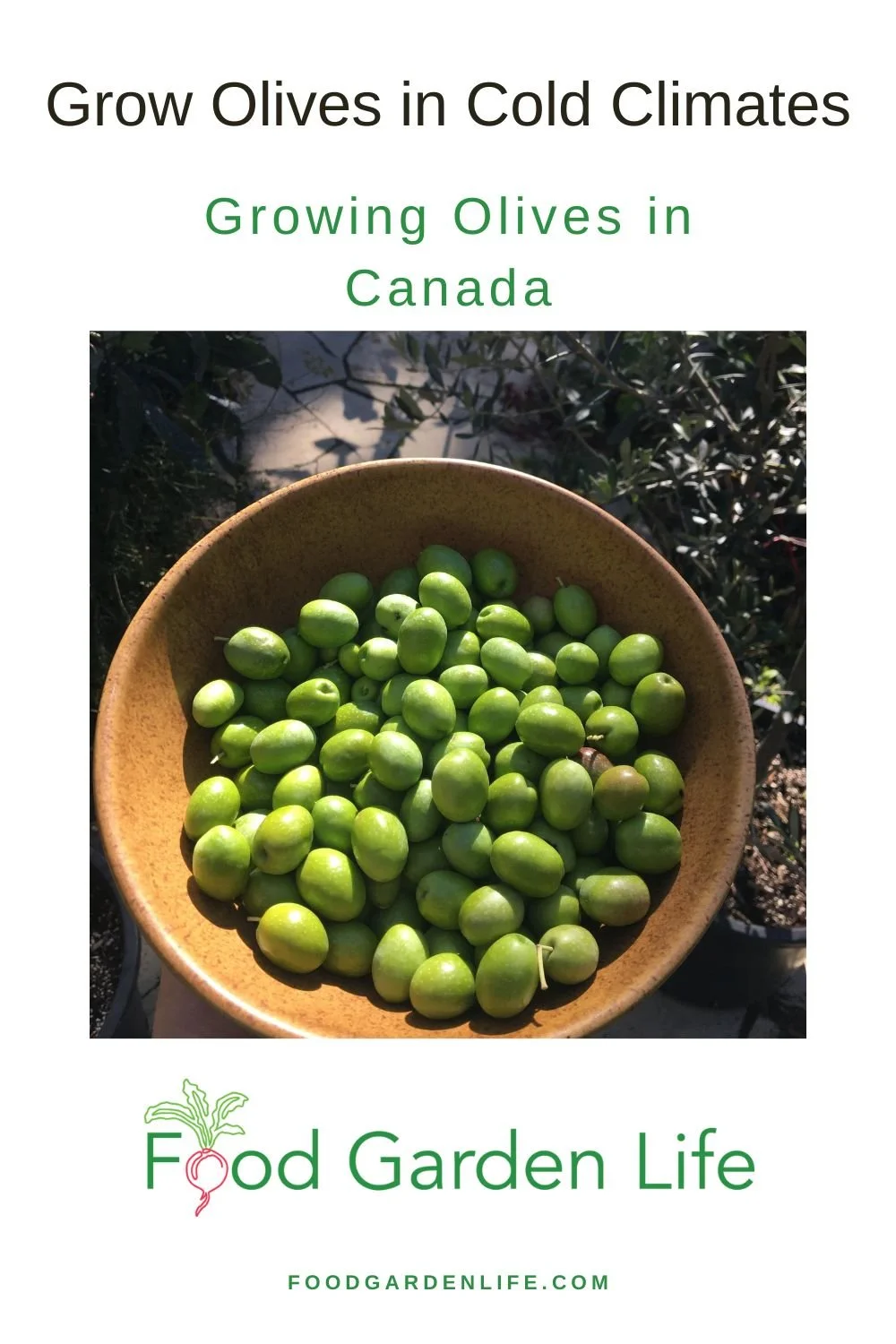

Growing Olives in Canada

Olive trees don’t survive winter temperatures in most parts of Canada…but there are creative ways to grow them.

As Bob Duncan points to the south and west walls of his house he tells me, “Don’t waste them on rose bushes!”

Duncan is near Victoria, British Columbia. And against these south and west walls he grows olive trees (Olea europaea).

While olive trees don’t survive winter temperatures in most parts of Canada, in the balmier parts of British Columbia they do.

“The trees are absolutely fine at -10°C,” says Duncan, owner of Fruit Trees and More nursery.“

Last year that one was thick with olives, thousands of them,” he says, pointing to a 10-year-old tree.

It’s not surprising that olives do well here, says Duncan. He explains that they are grown extensively in the Mediterranean basin, where winters are similarly cooler than summers.

Growing Olives in Southern B.C.

Bob Duncan, serving home-grown olives in British Columbia, Canada

Duncan grows olive trees flat against his house on a series of horizontal wires. If temperatures drop below -10°C (14°F), he drapes the outward-facing side of the trees with a floating row cover (a breathable, lightweight, cloth-like material).

He also has one other trick to protect the trees during cold spells: Old-fashioned incandescent Christmas lights. When temperatures get low enough, he turns on the lights, which emit just enough heat to keep the temperature in a safe zone.

Elsewhere in B.C.

Michael Pierce grows olives in the ground out in the open at his home on Saturna Island, B.C. His nursery, Saturna Olive Consortium, specializes in olive plants.

He says that while the climate on some of the southern Gulf Islands and around Victoria makes it possible to grow in-ground olive trees, it’s borderline.

“They grow more slowly because the growing season is shorter and the conditions are cooler,” he explains.

Duncan tells local gardeners not to waste the south- and west-facing walls on their property on roses…save them for olives!

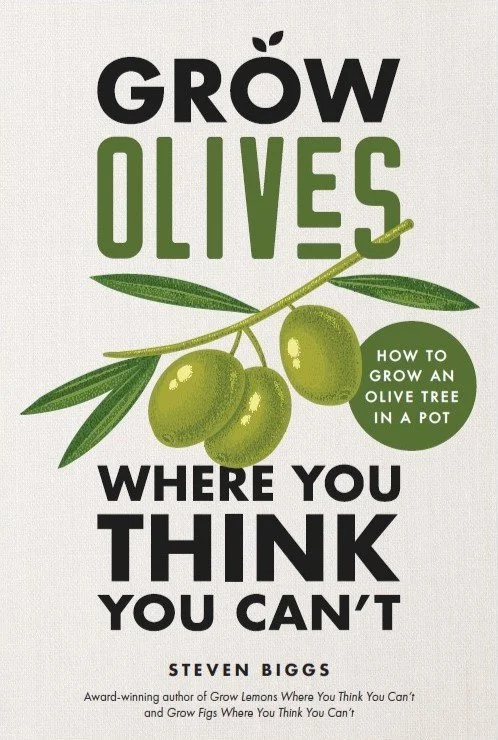

New Release for December 2024.

Now available for pre-order.

Even if you live somewhere too cold for olive trees to survive the winter, you can enjoy the exotic touch of an olive tree in your garden. This book gives you what you need to know to grow an olive tree in a pot. (And get olives!)

If temperatures drop low enough, Bob Duncan turns on the incandescent Christmas lights on his olive plants as a source of heat.

Growing Olives in Colder Canadian Climates

My own potted olive trees in Toronto survive winter in a cool sunroom, an insulated garage, and even in my dining room.

A friend overwinters hers by the south window in the house.

Find out more about how to grow an olive tree in a pot.

While they make attractive indoor plants, Duncan and Pierce both point out that without a cool spell, the flowering cycle of the tree can be disrupted. So if you overwinter them at room temperature, you might not get flowers and olives.

Don Moffat, who works as an ornamental gardener in Toronto, has helped clients overwinter olive trees. Smaller trees, he says, can be buried to protect them over the winter.

Duncan notes that while in-ground trees easily withstand -10°C (14°F), potted trees should be exposed to no more than a light freeze. “The roots are not as tough as the upstairs,” he says.

Getting Olives to Flower and Fruit in Canada

My original two olive trees—clones from the same plant—looked great but didn’t fruit for years. Duncan explained that they likely needed a cold spell. So I tweaked my overwintering technique to give them cold, bright conditions over the winter in a minimally heated greenhouse.

Duncan also explained that because my plants are both the same variety, and because olives are not usually self-fertile, I should get another variety.

My Toronto olive harvest!

While Duncan has seen plants in isolation produce some olives, “It’s better to have two varieties,” he says.

So I got a third olive tree—another variety. And between having two varieties, and providing a cold, bright spell over winter, my olives began to flower and set fruit.

Olive Pollination

“There is pollen everywhere,” says Duncan, as he talks about knowing when to help pollinate his olive trees, which are wind-pollinated. He uses a feather duster, or a vacuum set on reverse to blow.

I let nature take its course, and don’t help with the pollination of my olive trees.

Olive Harvest

Pierce usually harvests olives in November. Harvest time depends on the growing season, the variety, and stage of ripeness.

Olives can be picked green, when they start to turn colour or when fully coloured. The fruit can’t withstand temperatures as cold as the tree.

Maintaining an Olive Tree

Pin this post!

Olive trees do best in full sun. When grown in a pot, use a well-drained potting mix and feed with a balanced fertilizer in spring and summer. Keep potted plants well watered, but not constantly wet: Duncan advises that they be kept on the “dry side of moist.”

A young tree might need support until its stem thickens. Prune in spring to obtain the desired size and shape, removing crossing branches. Olives grow into small trees. Duncan’s reach up to the eaves of his house.

The size of potted plants is determined by the gardener. My own olive trees are in 14” pots; I prune the plants to six feet in height so they are easily carried through a doorway.

Plants that are grown from cuttings (as are most commercially available plants) are “physiologically” mature and will fruit while still small. Pierce says, “I’ve seen little, twelve-inch trees start to flower and get fruit.”

Olive Varieties

There are many olive varieties, and some are more tolerant of cold than others, says Duncan. Pierce finds the cultivars Frantoio and Leccino have good cold hardiness.

But for gardeners growing olives in pots and providing a protected spot for the winter, this cold hardiness is not as important as it is for people growing olives in the ground in southern BC.

My original two olive trees are an unnamed variety with olives that are large, plump, and green when I pick them here in Toronto in October. My third olive tree, which came home in the suitcase from Bob Duncan’s nursery, is a Frantoio, and it’s smaller olives are just starting to colour up as I pick from my olive trees before stowing them away for the winter.

More on Growing Olives in Cold Climates

Find out how to grow an olive tree in a pot.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Here’s More Exotic Fruit You Can Grow

If you get a kick out of growing things where they don’t normally survive, find out about how to harvest figs and lemons in cold climates:

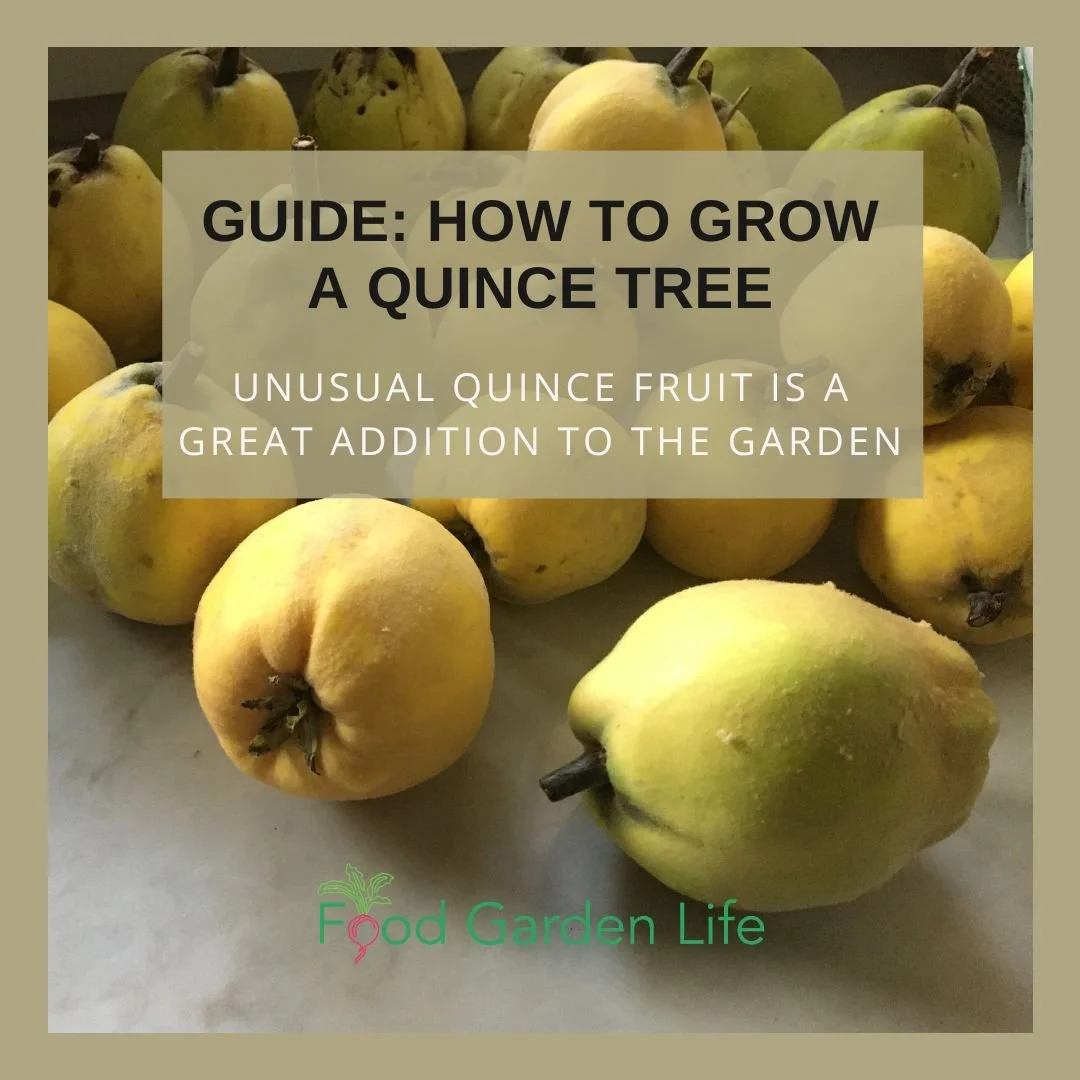

Guide: How to Grow a Quince Tree

Find out how to grow a quince tree. It’s an unusual fruit that’s easy to grow in a home garden. (And it smells amazing!)

By Steven Biggs

Unusual Quince Fruit a Great Addition to the Garden

Quince fruit grows as a bush or small tree, and is a great fit for a home garden or edible landscape.

It’s rock hard. But looks soft and fuzzy.

It’s tart. But smells sweet…so sweet you wish you could eat the smell.

It’s quince fruit. And since I started growing a trio of quince trees in my Toronto garden, I’ve had fun experimenting with this versatile ingredient.

It works well in desserts:

Added to apple sauce

In an apple pie

It’s also great in savoury dishes:

Cooked in a tangine with meat

Pickled or poached

In my part of the world quince is hardy—but rarely found in home gardens or orchards.

But that doesn’t mean there are no quince roots nearby…because quince is often used as a rootstock for pears and medlar. (Read more about medlar here.)

Quince trees are easy to grow, but rarely grown in orchards and home gardens.

How to Grow Quince

Quince is an easy-to-grow tree fruit suited to home gardens, edible landscapes, and food forests. This guide to how to grow quince tells you what you need to get started.

Quince (Cydonia oblonga) is a naturally dwarf tree that grows 3-6 metres (10-20 feet) high. This makes it a fine choice for home gardens.

(It’s different from a common flowering landscape bush called Japanese quince or flowering quince, Chaenomeles spp.)

The quince fruit tree is related to apples and pears, so it’s no surprise that the fruit can resemble either. Some varieties give pear-shaped fruit, while some are apple-shaped. They are fuzzy, and ripen to a golden colour.

Pin this post!

The fruit grows on year-old wood and short spurs. Branches often droop from the weight of the fruit growing near the tip.

Best Location for a Quince Tree

Sunlight

Quince trees do best in full sun, but are tolerant of partial shade.

Sun helps with fruit ripening, so in areas with a short growing season, the more sun the better.

Soil

Quince grows in a wide variety of soil types. A well-drained soil that holds moisture is ideal. Dry, sandy soils are the least ideal.

They tolerate more soil moisture than many fruit trees, meaning that if you’re planting your yard and have a spot with moist soil, save that spot for the quince tree. (Moist is OK; waterlogged is not.)

Amend light and heavy soils with organic matter before planting.

Quince Pollination

The solitary quince flowers look similar to apple flowers.

The solitary flowers look similar to apple flowers.

Quince trees are self-pollinating, which means you only need one tree to get fruit. However, you can get better yields if there is cross pollination with other quince trees.

Quince Pruning

Quince trees are naturally small, requiring less pruning than many other fruit trees.

You can grow your quince in a tree form or as a multi-stemmed bush. (See more on quince rootstock, below.)

Trees at garden centres will likely already have been pruned into shape for you (not always that well…)

If it’s an option, buy a “whip,” a young, single-stem, unbranched plant from a specialist nursery. This way you can shape it the way you want.

Pruning a Quince Whip - Formative Pruning

For the first couple of years, prune to develop the shape of your young quince tree.

A common approach with quince is to keep a length of unbranched trunk (about a metre, or 3 feet). Above that, develop an open-centred framework of branches. In short, an open-centred tree. (Think of a goblet!)

(This goblet shape is common because quince can be difficult to grow in a “central-leader” style, which has a main trunk.)

Prune back your whip to where you want branching to begin. It may seem harsh, but you’re pruning to induce side branching (There are buds that you don’t see that will grow into side branches as you prune the top off of your whip.)

When you have a choice between which branches to keep, and which to snip, a wider angle is better than a narrower angle.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Annual Quince Pruning

Once there’s a good branch structure on the quince tree, prune the annually in late winter, while it’s dormant. This annual pruning is to optimize the size and shape of the tree for fruit production.

We prune quince over the winter, while it’s dormant, to reduce the chance of fire blight infection. (See more on fire blight below.)

Here’s what to do:

Remove crossing and crowded branches…quince can get quite choked up with willy-nilly growth

Cut out dead and broken branches

Remove suckers that grow from the base

Trim back the top of the tree if it gets too high

Shorten side shoots

Remove shoots growing from the base of the tree (the unbranched portion of the trunk)

If you’re gardening in a small space and a tree form is out of the question, quince on dwarfing rootstock can be grown in a bush shape. Quince trees can also be trained into a fan shape and grown on a wall.

Quince Tree Rootstock

Like most fruit trees, commercially produced quince trees are usually grafted onto “rootstock.” (A variety with nice fruit is grafted atop a variety that has roots with a desirable trait, a.k.a. the rootstock.)

The choice of rootstock determines the size of the tree. Two common quince rootstocks are Quince A and Quince C.

Quince A rootstock is more vigorous than Quince C, allowing trees to get up to about 5 metres (15 feet) tall. It is suited to growing as espaliers and trees.

Quince C rootstock has a dwarfing effect, giving a tree that gets 3-4 metres (8-12 feet) tall. If you want to grow quince in a bush shape, look for this rootstock.

Home Quince Tree Propagation

Home gardeners might opt to grow quince from seed. It grows easily from seed. Just know that the seed will give you something different from the fruit it came from…perhaps better, perhaps not. You won’t know fruit quality, tree size, fruitfulness until your seed-grown quince tree matures...years later.

Seed-grown quince can be used as rootstock if you have known quince varieties that you want to propagate by grafting.

Quince trees can also be reproduced cuttings and layering (where you bury a low-lying branch.)

Quince Varieties

There are not many quince varieties available commercially. Some varieties have fruit with an apple-like shape; and some are pear-like. Here are three common quince varieties that I’ve seen for sale here in Ontario:

Meeches Prolific. Vigorous variety with flavourful fruit.

Champion. Medium fruit on a vigorous plant.

Vranja. Strongly scented, large fruit.

Planting Quince Trees

Prepare the ground as you would to plant most trees and shrubs, by digging a hole that’s as deep as the roots—but wider.

Once the tree is in the ground, check to make sure that you’ve planted it at the same height—not deeper, not shallower. Then backfill the hole using soil amended with compost.

Get Your Fig Trees Through Winter

And eat fresh homegrown figs!

Quince Tree Spacing

Because it’s a small tree, it’s great for home gardens. I have a trio of quince trees in a 3 x 3 metre patch (9 x 9 feet).

As with other fruit trees, the spacing recommended for orchards isn’t needed for a home garden.

Remember that seed-grown trees and grafted plants on Quince A rootstock need more space than trees grafts on Quince C rootstock.

Quince Trees in Permaculture and Forest Gardens

Because quince trees are relatively short and tolerate some shade, they can be useful when developing plant layers in a garden.

For example, taller trees can be hemmed with quince, under which are shade-tolerant fruit bushes such as currant. Think of a forest edge setting.

Using Quince Trees in Garden Design

Fuzzy young quince leaves have a silvery colour.

Quince is a great dual-purpose tree—edible and very ornamental.

The fuzzy leaves, springtime bloom, attractive fruit, gnarly branches, and peeling bark on older trees make them stand out in the landscape, particularly in winter.

(And if you’ve ever been smitten with the silvery sheen that comes from an olive tree, young quince leaves have the same effect. Read more about potted olive trees here.)

Quince Tree Care

Grown in a fertile soil, you might find that the only annual care you need is pruning.

If feeding, the main caution is not to give too much nitrogen. That’s because too much nitrogen stimulates rapid vegetative growth—and that growth is more susceptible to fire blight (see below). For this reason, avoid composted animal manures, and instead choose composted leaves when amending soil.

Quince Tree Hardiness

Where do quince grow? Quince trees are less hardy than apples, generally hardy in USDA zones 5-9. They can take temperatures down to about -26°C (15°F).

BUT…many gardeners grow them in colder zones. If you’re gardening in a cold climate, look for varieties recommended for borderline areas—and when planting, look for protected microclimates.

Want tips on planting fruit in cold climates? Tune in here.

Interested in hardy apples? Check out this episode of The Food Garden Life Show.

Quince Tree Challenges

As a relative of apples and pears, quince suffers from many of the same afflictions.

Fire Blight

Fire blight on quince.

This bacterial disease is the scourge of European pears, quince, apples, mountain ash, and hawthorn. The bacteria get into the plant through flowers, wounds, and pruning cuts made early in the year.

That’s why it’s best to stick with winter pruning for quince.

With fire blight, you’ll see leaves suddenly wilt and then turn brown, giving a scorched-like appearance. When that happens, prune back at least 10” below the infected area. Don’t prune around flowering time. Clean your pruners with alcohol or bleach between cuts to avoid spreading the disease.

Fire blight is more of a problem in areas with warm, humid conditions.

Codling Moth

The young caterpillars of this moth tunnel into the fruit, and exit a few weeks later, well before you harvest your quince. Like all pests, some years there are more…and some, fewer.

In a home garden setting, I suggest accepting coddling moth. They go to the core, for seeds—and since you cut up quince before eating it, can cut out the tunnel and the core, removing evidence of these pests in the quince you’re using.

Squirrels

As an urban gardener, squirrels are my biggest quince challenge!!!###.

The main things they do to my quince are:

Bite marks on young fruit as the squirrels taste their way around my garden

Outright fruit theft as the quince fruit ripen

If you don’t have too many quince fruit, consider using organza bags over the fruit as a deterrent. Netting is possible too if you have a short tree or a bush (but it’s ugly!)

Bite marks on young fruit as the squirrels taste their way around my garden.

Harvest Quince Fruit

Harvest quince in the autumn, as they turn a golden-yellow colour. Pick before frost for best fruit quality.

Note: Even though quince fruit are hard as rocks, they bruise very easily. Be gentle.

Pick quince with secateurs in hand as the fruit don’t easily break off from the stem like apples do. By cutting off the fruit you’ll avoid damaging branches.

Store Quince Fruit

The fruit continues to ripen once picked and stores well in a cool, dark area free from frost. Having said that, I often just leave quinces on my kitchen counter until I’m ready to use them. They can last a number of weeks. They don’t last quite as long as they would somewhere cooler…but with the volume of quince I grow they’re long gone well before we get to that point. And they look beautiful and smell amazing.

Because quince has a strong scent, store away from other things that could absorb the smell. (Yes, away from your apples…unless you want them to taste like quince!)

Quince Fruit in the Kitchen

I often leave quince fruit on my kitchen counter until I’m ready to use it.

If you’re new to quince, use them in a simple recipe where the flavour shines through. Here are ideas:

Poached in a light syrup with vanilla and lemon juice

Added to apple sauce

When you make jam from quince, it changes colour and goes pink, then red. It’s beautiful! And on that note, quince fruit is very high in pectin, making it very well suited to using for preserves.

Here’s a recipe book dedicated to quince: Simply Quince, by Barbara Ghazarian.

Quince Tree FAQ

What if I forget to prune one year?

Your tree will be fine if you don’t prune. We prune to maintain the size and shape, and optimize fruit production.

Is it the same as my flowering quince?

Your flowering quince is sometimes called Japanese quince (Chaenomeles spp.). it, too gives rock-hard pectin-rich fruit.

When should I take quince cuttings?

When you prune your quince trees in late winter, keep that wood for use as cuttings.

AND here’s something you can do with any remaining quince branches you’ve pruned from the trees: Quince wood gives a flavourful smoke and is excellent for smoking meat. Use it in a smoker, or add it to a charcoal BBQ to enhance the flavour.

See how I roast my Thanksgiving turkey on a charcoal BBQ.

More on Growing Fruit

Fruit for Northern Gardens Masterclass

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Fruit Articles

Fruit Interviews

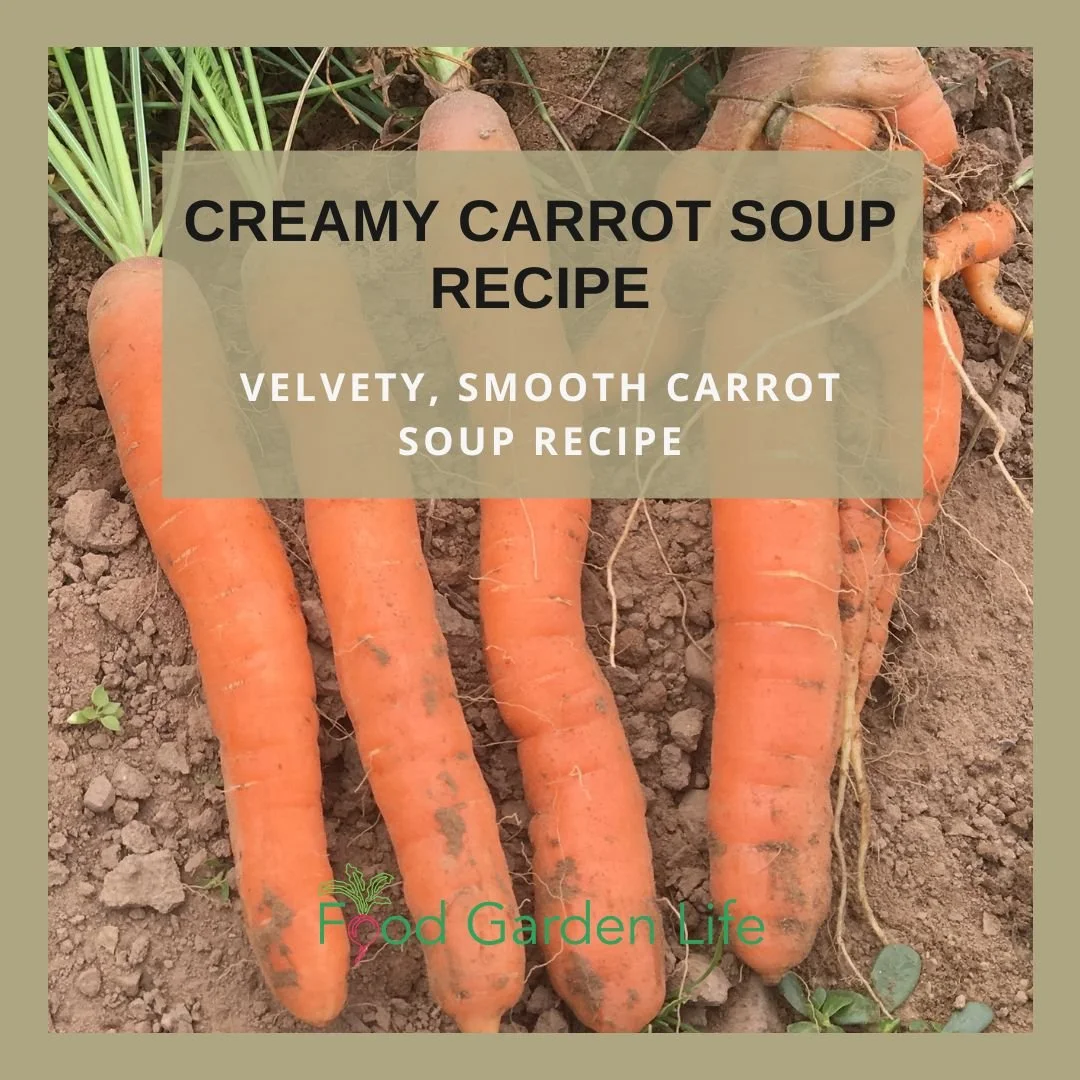

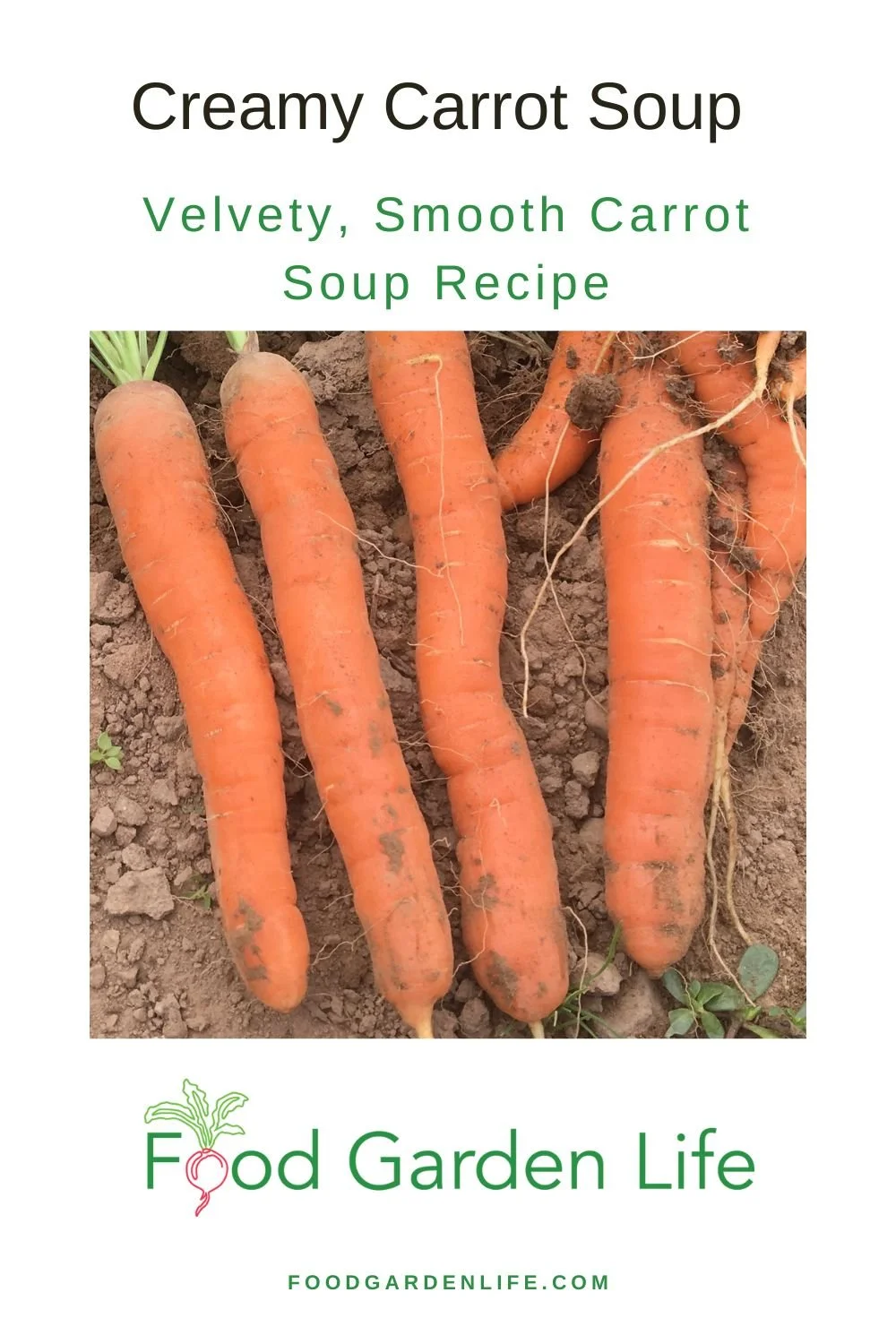

Mom’s Creamy Carrot Soup Recipe

Try this velvety Cream of Carrot soup recipe.

By Steven Biggs

An Impulse Buy and Lots of Carrot Soup with Cream

A velvety carrot soup with cream.

It was an impulse buy. Pure and simple.

But a bushel of carrots for $10? I couldn’t help it.

“They’ll keep nicely in the basement,” I thought to myself.

They didn’t. My basement is too warm…even my unheated storage room.

I needed to do something with the carrots quickly,before they spoiled.

So into the stockpot they went. That fall, my family ate a lot of smooth, velvety, cream of carrot soup.

(A bushel of carrots makes a lot of this pureed carrot soup!)

Luckily, this cream of carrot soup freezes well. So make up a big pot of this carrot cream in the fall, and enjoy it through the winter.

Finding Carrots in Bulk

Look for seconds…those imperfect carrots that don’t make the grade so they get sold in large quantities for very little.

I often see seconds at farm markets in the fall.

Grow Your Own Carrots

Cream of carrot soup is a great way to enjoy homegrown carrots.

Carrots are a great home garden crop. I start planting them in spring, and continue planting until August—and then harvest right into the winter. (Cover carrots with a straw bale to extend the harvest window as the ground freezes.)

Carrots are also an excellent succession crop to follow other crops. Find out more about succession crops.

For gardeners who are interested in a year-round harvest, carrots and onions are great storage crops—even if you don’t have a root cellar. Find out how to store them—and find out 25 storage crops you can grow in your garden.

Serving Ideas - Cream of Carrot Soup

Serve with homemade garlicky croutons sprinkled on top.

(Don’t add the croutons too soon…only at the last minute, so they don’t get soggy.)

Dill seed in the garden.

Secret Ingredient – Dill Seed

Dill seed is like little nuggets of dill flavour. It’s easy to grow your own dill seed; just let a couple of dill plants flower and go to seed, and then harvest the dill seed once it’s dry.

I also use dill seed in my homemade beet borsch. Here’s Mom’s borsch recipe…it’s fantastic!

If you don’t have dill seed, chopped dill works well instead. Add it at the end, when you add the cream.

Recipe for Mom’s Cream of Carrot Soup

Mom made this soup every fall…but not using bushels of carrots, as I did in my cream-of-carrot misadventure.

Ingredients

Pin this post.

Onion, coarsely chopped (I use 2 onions, adjust to your preference)

1 tsp curry powder

1 tsp. dill seed

5 cups chicken stock

2 lbs. coarsely chopped carrots

1 cup cream

I often use my homemade turkey stock in this recipe instead of chicken stock. I make turkey stock from my BBQ-roasted turkey. Find out how I roast turkey on my charcoal barbecue.

Directions

Brown onions in butter in the stock pot (don’t rush this step…if they’re not browned, they’re not as sweet and flavourful)

When onions are browned, add the rest of the ingredients

Cook for about half an hour, until the carrots are soft

Blend (mom always did this in her blender, but I find a hand-immersion blender is easier)

Add cream

More Cooking Ideas

More on Growing Your Own Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Courses

Want a Bold Vegetable? Grow This Promethean Plant (the Cardoon)

Grow Cardoon, a bold, beautiful vegetable that has great ornamental appeal.

By Steven Biggs

A cardoon plant is beautiful, enormous, and edible.

Cardoon Plant is Beautiful, Enormous, and Edible

“I MUST KNOW THE NAME OF THE PROMETHEAN PLANTS IN YOUR FRONT YARD,” exclaimed the caller, describing bold, arching, grey leaves.

I was delighted by the call, mainly because I love talking about plants—but also because I learned a new word.

I Knew which Plant the Caller Meant

I knew right away the plant in question was cardoon (Cynara cardunculus). The caller was captivated by the four-foot (1.2-m) tall, silver-grey, spiny-leaved plants arching over the edge of my driveway.

Cardoon resembles its cousin, the globe artichoke, but has bigger leaves.

Cardoon plants had prime front-garden real estate because they fit the edible theme I have for the space. Cardoon leaf stalks and flower buds are edible. (And you can do something else with it too…keep reading.)

Pin this post!

An Annual Around Here

Is cardoon perennial?

A perennial in warmer climates, cardoon grows as an annual in many parts of Canada.

Many years mine die over the winter here in Toronto, Canada.

But sometimes, with the right combination of mild temperatures and an insulating blanket of snow, they survive.

When they survive the winter and grow for a second season, they flower.

Cardoon Flowers

Cardoon flowers are smaller than globe artichoke flowers, but look very similar.

They are purple and thistle-like, arriving mid-late summer.

When you grow cardoon as an annual, starting with new seedlings every year, there’s a good chance it won’t flower. It flowers in its second year.

If you’re growing cardoon as an annual and do want flowers, here’s a trick:

Give the plants a chill treatment, which tricks the plant into blooming in its first year.

Chill Treatment for Cardoon Seedlings

Chill young plants before planting out in the spring to induce flowering. (Cold-climate artichoke growers do the same thing.)

Put the seedlings somewhere cold—but not freezing—for about 10 days.

A fridge works well; or put them outdoors on cool days, and move them somewhere protected overnight so they don’t freeze.

Can You Eat Cardoon Flowers?

I was told by a Palestinian chef that while the leaf stalks are what is eaten in Southern Europe, in parts of Palestine it’s the flower heads that are eaten. I have not yet tried cooking the heads—but it’s on my to-try list.

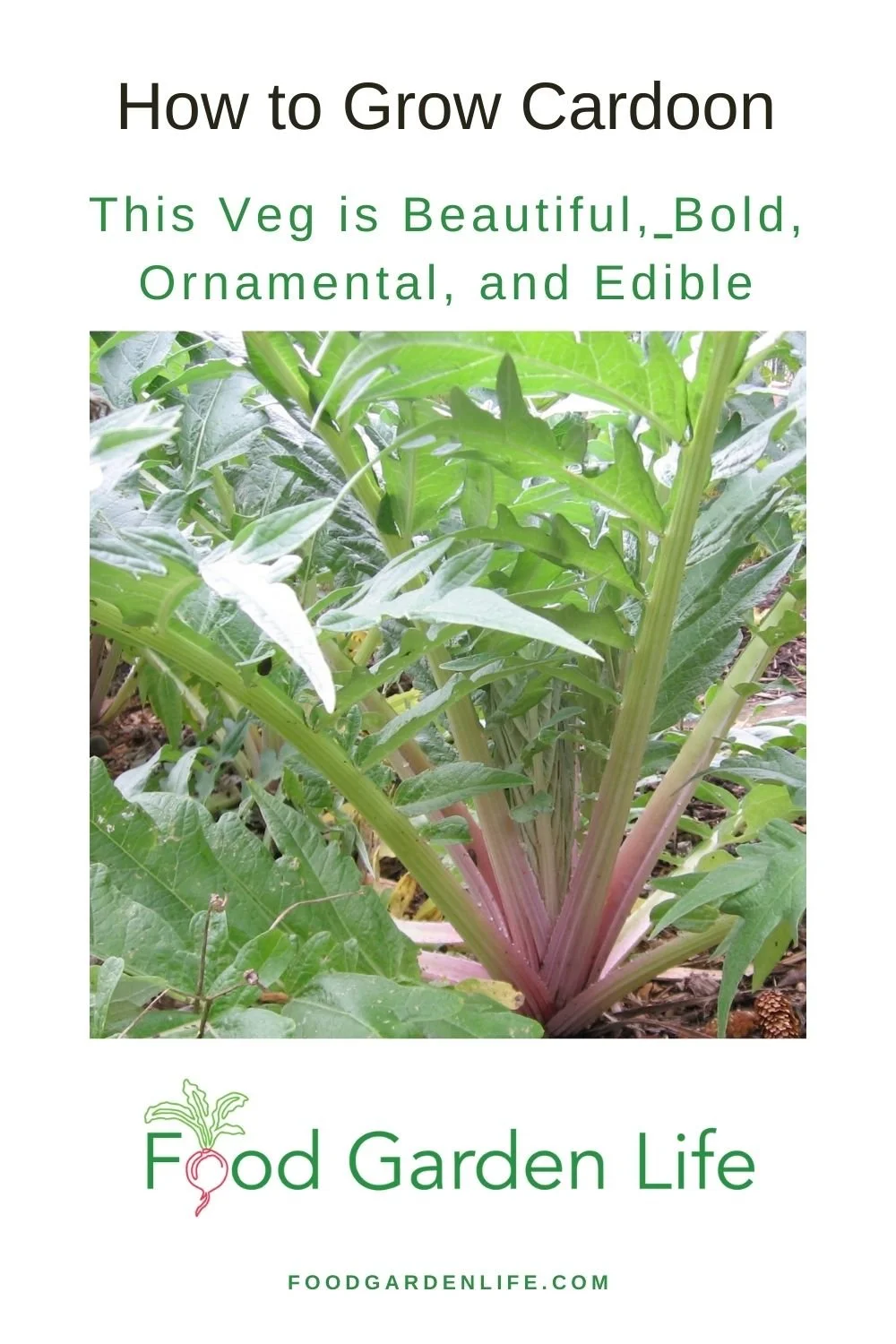

Grow cardoon, an edible and attractive relative of the artichoke. Pictured is ‘Rouge d’Alger’ cardoon.

Grow Cardoon From Seed

Cardoon transplants are a rare find at garden centres. Luckily, it’s easy to grow cardoon from seed.

(If you don’t find cardoon seeds in the vegetable section of seed catalogues, check under annuals.)

Start cardoon seeds indoors, about 10 weeks before the last spring frost. Transplant outdoors after the risk of frost is over.

Another advantage to growing cardoon from seed is that you can grow a showy variety such as ‘Rouge d’Alger,’ which has red-tinted stalks.

Cardoon In the Garden

How to Blanch Cardoon Stalks

If you grow cardoon, wrap it with cardboard, newspaper, or burlap (pictured here) to get a milder flavour.

To get cardoon stalks that are whiter, more tender, and less bitter, blanch them.

Blanching simply means excluding sunlight.

To blanch cardoon stalks, wrap the bottom 12 inches (30 cm) of the plant in cardboard or newspaper two to four weeks before harvesting

Harvest inner stalks, not outer the more stringy outer ones

I’ve also seen cardoon stalks wrapped with burlap or fabric.

Find out how to blanch vegetables in the garden.

Grow Cardoons in Containers

If you’re gardening in a small space, you can still grow cardoon, either as an edible or an ornamental plant. Cardoon grows very well in containers.

Cardoon in Edible Landscapes

While cardoon is a sun-loving plant, it grows respectably well in partial sun, making it very versatile for use in an edible landscape.

Cardoon for Fall and Winter Interest

Cardoon plants soldier on when cold fall weather arrives. When brushed with frost, they droop a bit, and then spring back as the sun burns off the frost.

As very cold weather with hard freezes arrives, the cardoon plants will be done for the year.

Cardoon as a Cut Flower

No need to say too much here. These bold, dramatic flowers are a great addition to flower arrangements.

Cardoon in the Kitchen

How to Eat Cardoon

I’ve sent home many visitors with leaf stalks from that dashing row of cardoon plants in my front yard.

But take care if you’ve never cooked it!

“Wow, that was disgusting!” my wife and I stammered to each other after our first attempt at eating steamed cardoon.

But I’ve heard from people who love cardoon, and a festive seasonal cardoon soup served in parts of Italy.

Preparing Cardoon Stalks

Use a knife or vegetable peeler to remove the stringy, outer part of the stalk.

Inner stalks on plants that have been blanched are less stringy.

Best Way to Cook Cardoon

I have found that the best way to cook cardoon is to cut stalks into inch-long (2.5-cm) pieces, then bread and deep-fry them, giving crunchy morsels that are a perfect vehicle for a dip.

Minimize Bitterness

Cook cardoon to minimize bitterness, using these pointers from a chef who heard about my reaction the first time I cooked it:

Deep frying helps counter bitterness

Add salt to the water if boiling cardoon (and it’s best to change the water at least once during cooking)

Or roast and lightly char stalks to counter bitterness

Other Ways to Use Cardoon

Cardoon as Rennet Substitute

Extracts from the cardoon flower are used to make a vegetarian substitute for rennet—which is used to make cheese.

Shopping for Cardoon Stalks

Cardone Vegetable

If you want to buy cardoon stalks, they might not be labelled “cardoon.”

At a local grocery store, cardoon stalks are labelled as “cardone.”

More Vegetable Gardening Ideas

More Mediterranean Crops to Grow in Cold Climates

Guide to Growing an Olive Tree in a Pot

Intro to Growing Figs in Cold Climates

How to Grow Artichoke in Northern Climates

Guide: How to Grow Lemon Trees Indoors That Actually Produce Lemons

Courses to Help You Grow Mediterranean Crops

Books to Help You Grow Mediterranean Crops

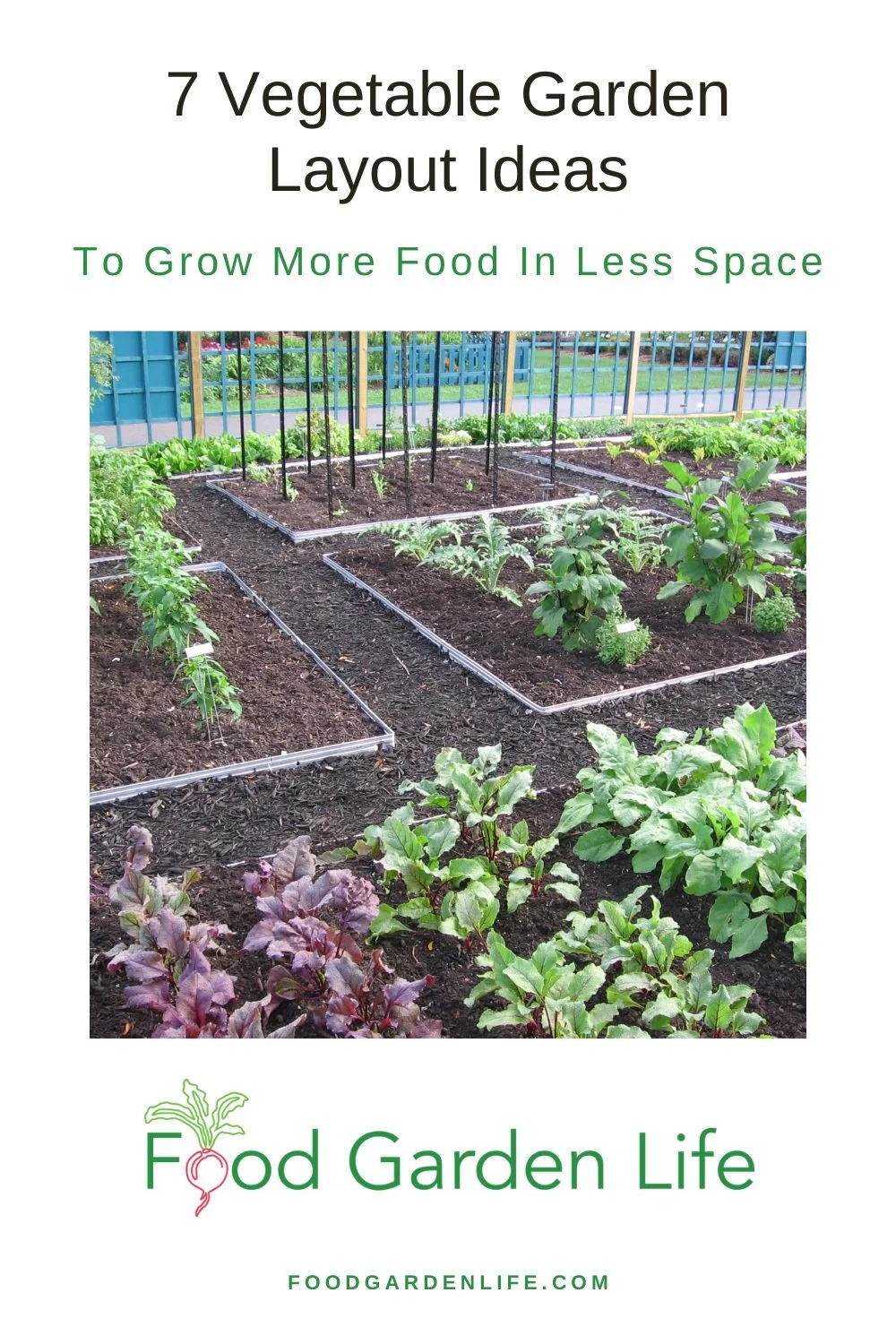

7 Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas To Grow More Food In Your Garden

By Steven Biggs

Garden Layout for Vegetables

Need help planning a vegetable garden layout? Here are ideas to get your started!

I was delighted when a neighbour removed her front lawn to grow vegetables.

One more edible garden in the neighbourhood! It's a nice departure from the driveway-and-shrub aesthetic around here.

She asked me to help her plan her vegetable garden layout.

But...

I didn’t have a simple explanation about how to make a vegetable garden layout! Keep reading, because this inspired me to map out the way I think when I'm veggie gardening.

As we studied her small, partially shaded front yard, I saw numbers in my mind—distances between plants, between rows, and between crops. I saw centimetres and inches (because we’re in Canada and can’t decide on which to use.)

There's a simpler approach, and I share it below.