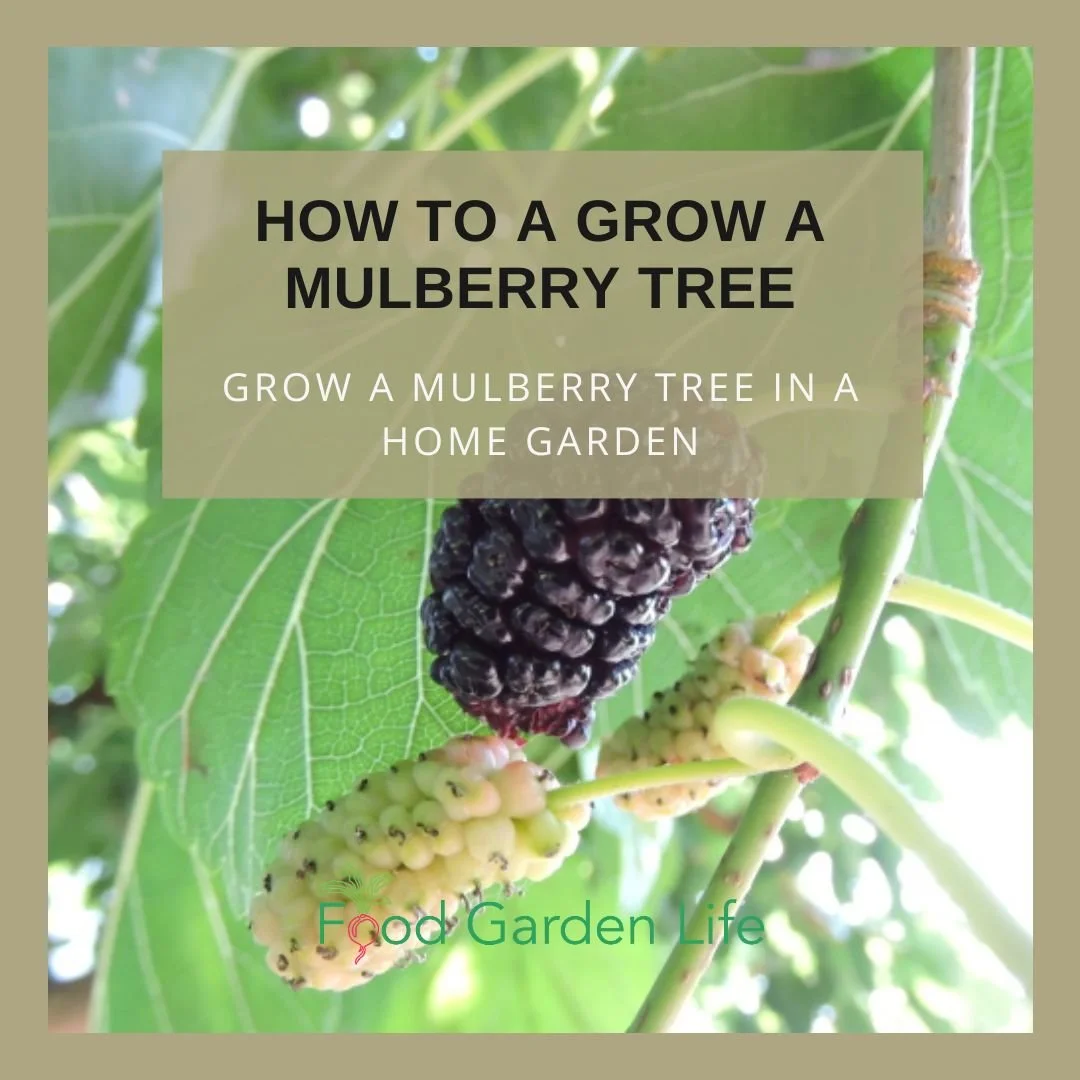

How to a Grow a Mulberry Tree

How to grow mulberry in cold climates.

By Steven Biggs

Fowling in Love with Mulberry

My neighbour Hubert handed me a pheasant and a duck from his freezer. I was working for the summer in a rural part of the UK, and regularly saw pheasant when I went out for a jog. Now I’d get to taste one!

As a 20-something-year-old, I’d never cooked either before…and had never even tasted pheasant.

But I remembered reading that the meat is rich and dark, well-suited to a tangy accompaniment.

And I remembered a mulberry tree in a nearby hedgerow.

I’d been grazing fruit from the mulberry tree every time I walked past it. But I had yet to cook the mulberry fruit.

This was my chance! Not really sure what I was doing, I made up a mulberry-Cointreau sauce for basting the roast. The company I had for supper thought it was pretty good.

Roasted fowl with mulberry-Cointreau sauce cemented my appreciation for the taste of mulberry.

Mulberry for Home Gardens

There are many types of mulberry suited for gardens in cold climate. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

Mulberries gets a bad rap. Mention mulberries and many people picture polka-dot-stained sidewalks and bird-bespattered cars. Or experienced gardeners worry that it’s a weedy plant.

Why is it that gardeners always want what’s difficult to grow? Why not appreciate what grows on its own?

This fruit does not play hard-to-get.

Mulberry is a great fit for home gardens because it’s:

Fast-growing

Hardy

Problem-free

Tolerant of many conditions

Very fruitful

And it’s a fruit that you likely won’t find for sale at grocery stores. Too fragile to ship when ripe.

Too bad mulberries get a bad rap for being vigorous growers.…and for the purple stains from falling fruit. They’re a great fruit for home gardens in cold climates.

What does a Mulberry Tree Look Like?

What does it look like? The question should really be, “What does a mulberry tree look like when pruned to feed people, not birds. (More on that below.)

Don’t grow this as a specimen shade tree. There are nicer shade trees out there.

Grow mulberry as a fruit-producing crop – which means you’ll keep it much smaller than if left unchecked.

Types of Mulberry for Cold Climates

Mulberry names don’t describe the fruit colour. That means a white mulberry tree could be black-fruited, red-fruited, or white-fruited.

If you’re shopping for a mulberry tree, here at the three types you’re likely to find in North America:

• White mulberry (Morus alba)

• Red mulberry (Morus rubra)

• Black mulberry (Morus nigra)

Mulberry names don’t describe the fruit colour. While this ‘Carman’ white mulberry fruit is white, other white mulberry varieties can be purple or black. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

For cold-climate fruit growers, it’s the white mulberry and its hybrids with the red mulberry that are hardiest, some into USDA zone 4.

I’ve read articles in British gardening magazines that disparage the less flavourful white mulberry…but it’s what we have.

White mulberry can grow up to about 15 metres (50’) tall. Because it grows easily from seed—and because birds quickly spread the seeds—feral white mulberry trees are common. (It’s considered a weed tree in some jurisdictions.)

Red mulberry is a native of North America. Pure red mulberry trees are rare because feral white mulberry and red mulberry hybridize readily. Here in Ontario, where red mulberry is native in the south of the province, its threatened by the white mulberry due to their promiscuous hybridizing.

The more diminutive black mulberry, noted for the quality of its fruit, is less hardy, and not suited to northern gardens. It’s suited to conditions in USDA zones 6 and higher.

Other thoughts on selecting a mulberry tree:

There are weeping varieties that get to about 3 metres (10’) tall and can be perfect for small-space gardens (just beware, as there are fruitless varieties of weeping mulberry on the market)

There are dwarf varieties that get to about 6 metres (20’) tall

White-fruited varieties might be the ticket is you’re averse to mulberry stains

‘Illinois Everbearing’ is noted for having a long season of fruiting

Plant a Mulberry Tree

Mulberry trees fend for themselves quite well once established, but here are things you can do to give them a good start.

If you’re planting a container-grown mulberry tree, the first thing to do is look at the roots. Because mulberry is a vigorous grower, it’s common to find roots tightly wound around and knitted together.

Use your fingers to tease apart the roots. We want the roots to grow outwards into the surrounding soil once planted, not continue to grow around in circles.

Water well when first planted and until established.

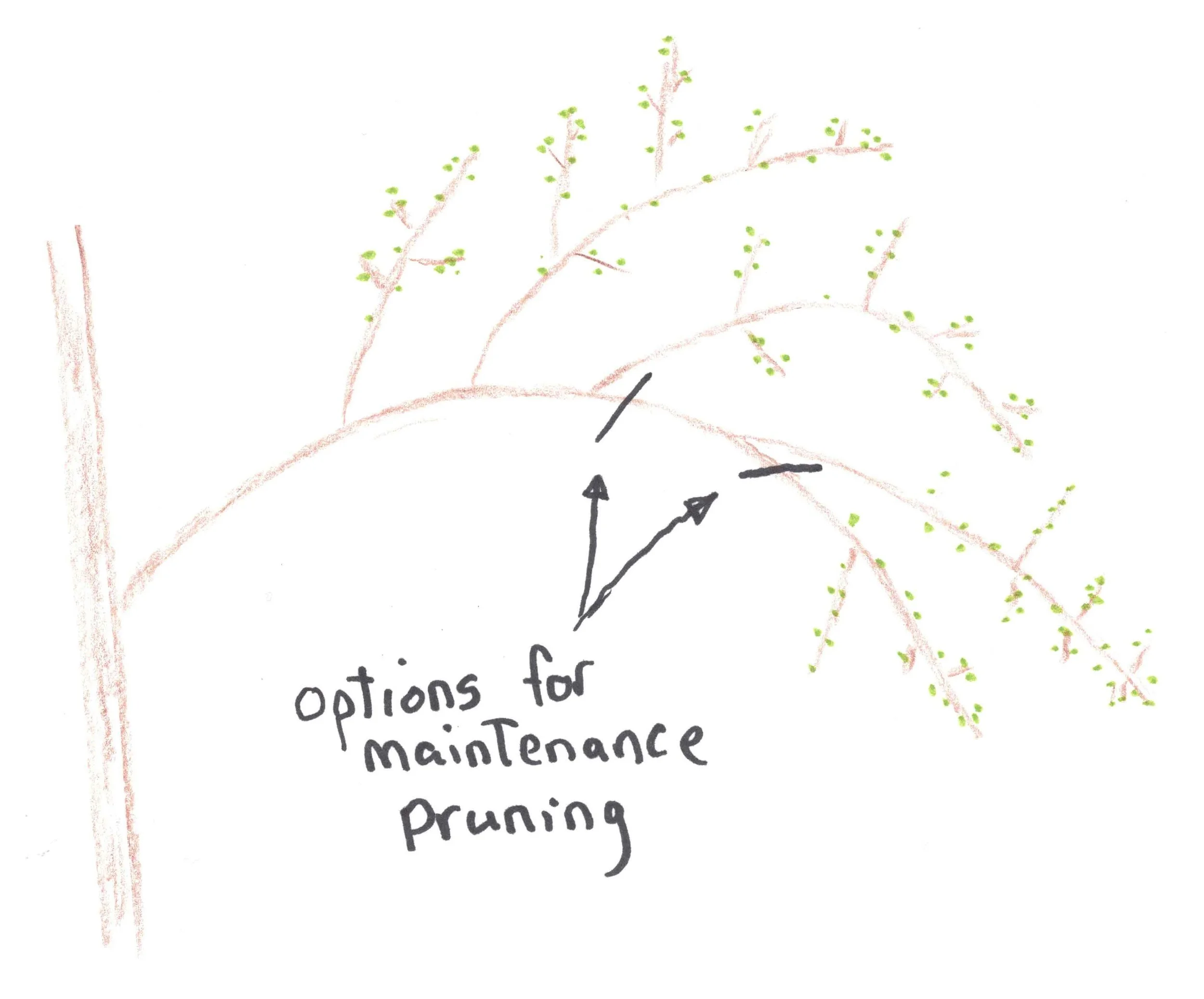

Pruning Mulberry Trees

Many sources suggest that regular pruning is not necessary with mulberry.

That’s fine if you want to feed the birds.

But if you’re growing the mulberries for yourself, I suggest a different approach: Be aggressive – and do it every year.

Your goal is to create a permanent scaffold of branches that you cut back to every year (see below).

Formative Pruning

Grow mulberry trees in an umbrella shape, so you can reach all of the fruit. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

The best way to get a tree with a well-arranged scaffold is to make it yourself. Get a whip, which is a young, unbranched tree. (You probably won’t find this sort of tree at a garden centre; look for a specialist fruit-tree nursery.)

Then prune that whip so that it grows into a spreading tree. Think short and wide.

Start this pruning process by removing the “leader,” which is the growing tip of the tree. Linda Grimo, at Grimo Nut Nursery, a specialist nursery, suggests, “Stand as tall as you can with your pruners in your hand and clip off the top of the tree.” She explains that this stops it from growing upwards, and encourages the growth of side branches at a height you can reach without a ladder.

Umbrella-shaped mulberry tree in summer. Prune hard to keep berries at picking height. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

Grimo says she likes to grow mulberry trees in an umbrella-shaped scaffold, with side branches (laterals) spaced out around the tree. For ease of getting under the tree to pick, don’t grow the side branches too low on the tree; her preferred height is just over a metre (4’) above the ground.

Annual Pruning

Mulberry trees growing in good soil put on a tremendous amount of growth every year. After formative pruning is complete, prune back almost all of the new growth every year, leaving just 1-2 buds from which the tree can send up replacement shoots.

This harsh pruning doesn’t affect cropping because fruit forms on new growth. “Don’t be afraid, you can’t kill a mulberry tree,” is what Grimo tells concerned first-time mulberry growers.

Prune in late winter, when dormant.

Mulberry Tree Feed and Water

Mulberry trees have extensive root systems, which means that they can do quite well without coddling.

Mulch with compost around the base of the tree to feed the soil and suppress weed growth.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Mulberry Tree Pollination

Mulberry trees are self-fertile, which means you only need one tree to get fruit.

The small, unremarkable flowers are wind pollinated. (There are even some varieties that set fruit without pollination.)

Mulberry Tree Propagation

Dwarf or weeping mulberry varieties are well-suited to use in small-space foodscapes, even in more traditional gardens.

Mulberry plants grown from seed will be different from the parent plant. Just like apples. There is a juvenile period before a seed-grown mulberry tree will flower and produce fruit, often 5-10 years.

It’s easy to grow from seed. In fact, this is a tree that might just seed itself in your garden.

I don’t recommend growing mulberry from seed, because you don’t know what the fruit quality will be like—and you’ll have to patiently wait through that juvenile stage.

Another unknown if growing from seed: Some mulberry trees are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are on separate plants…and that could leave you with a tree that doesn’t bear any fruit.

If you want good fruit quickly, start with a known variety. Clonally produced trees—grafts and cuttings—can fruit right away because the clone is from a mature tree, and no longer in the juvenile stage.

Some nurseries propagate mulberry by cutting, some by grafting. For grafting, Grimo says cleft grafts work well. Propagation from cuttings can be more challenging for home gardeners without a misting system, bottom heat, and rooting hormone.

Mulberry Trees in Garden Design

Mulberry trees are quite versatile in garden design. Here are ideas for using mulberry trees in the landscape:

Dwarf or weeping varieties are well-suited to use in small-space foodscapes

Large, minimally pruned mulberry trees can be used for a canopy layer in a food forest

Smaller mulberry varieties can fit a forest-edge niche in a food forest because the tree tolerates partial shade

From a permaculture perspective, mulberry is an interesting option because along with fruit, it can provide poles and animal fodder (see below)

Mulberry for More than the Fruit

Because it grows very quickly, mulberry is well suited to pollarding and coppicing techniques. Here are branches from my neighbour’s mulberry pollard that I use as poles in the garden.

Mulberry is an excellent tree choice if you’re gardening with a permaculture mindset.

My neighbour Troy used to give his mulberry tree a harsh haircut every year. The long, straight branches made excellent poles that he gave me for staking plants and making trellises.

He grew his tree as a “pollard,” meaning he lopped off all of the growth a few feet above the ground. (Pollarding is often done with catalpa trees, for ornamental purposes.)

The other twist on this idea of using your mulberry tree to produce poles, is to grow it as a “coppice.” Coppicing is when you cut off a tree close to the ground to get it to send out lots of stems. Coppicing has traditionally been used to produce wood for baskets, fences, and fuel.

Mulberry Tree Location

Mulberry trees prefer full sun and rich soil. But they tolerate partial shade and a variety of soils.

And much worse.

To say they’re forgiving of poor conditions is an understatement.

I’ve seen lovely mulberry trees growing between cracks in the pavement. They do amazingly well in inhospitable locations. As I write this I’m looking out the window at the self-seeded mulberry tree in my front garden that I’m training into an espalier. It’s growing right underneath a row of spruce trees, hardly an ideal location. But it persists!

So save the prime real estate in your garden for plants that really need it. Your mulberry isn’t fussy. And, remember, pick a spot where purple spotting is not a nuisance.

The one thing to avoid is standing water. Pick a well-drained location, though occasional wetness is fine.

Challenges

Your mulberry tree will be a bird beacon.

Got a white car? Hanging out clothes to dry?

Then you might want to net the tree to keep away the birds. Netting is easier to do when you’ve grown a compact mulberry tree.

Harvest and Store Mulberries

If you’ve started with a tree grown from a graft or cutting, you might start getting fruit in as little as 2-3 years.

Not all the fruit on a tree ripens at the same time. As they ripen, fruit fall to the ground.

White mulberries can be very sweet, while black mulberries are more balanced, with some tartness. I prefer white mulberries a little bit under ripe—while they’re less sweet. (Remember, a white mulberry tree can have black fruit!)

A couple notes on picking mulberries:

The fruit are fragile, and the juice easily comes out of the fruit when picked…so expect red hands if it’s a dark-coloured variety

Ripe fruit will drop from tree as you pick

A common recommendation when harvesting from large mulberry trees with many unreachable fruit above is to place a sheet on the ground and shake the branches.

The fruit has a short life once picked. There’s a little stem on it – and you can eat it stem and all.

Here are 6 simple ideas to grow lots of fruit in a home garden.

Mulberries in the Kitchen

You can use mulberries raw, use them in preserves, or cook them. Here are ideas:

Mulberry pie

Mulberry wine

Mulberry cobbler

Mulberry liqueur

Dried mulberries (great in a trail mix!)

Mulberry juice

Mulberry FAQ

How fast do mulberry trees grow?

Mulberry trees grow very quickly.

Where do mulberry trees grow?

White mulberry and its hybrids are suited to cold-climate gardens into USDA zone 4. Black mulberry is less cold-tolerant.

Can you grow a mulberry tree from a cutting?

Yes. You can grow mulberry trees from cuttings.

Do mulberries grow on trees or bushes?

Mulberries naturally have a tree form, but you can prune to encourage branching and a bush-like shape.

Can you grow a mulberry tree in a pot?

Cold-climate gardeners who are determined to try black mulberry can grow it in a pot that is stored in a protected area over the winter.

How do you keep a mulberry tree small?

Prune it very aggressively every year.

Do mulberry trees grow near black walnut trees?

Mulberry trees are not affected by the compound “juglone” that is given off by black walnut trees. So if a black walnut tree has limited your growing options, consider mulberry.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Fruit

Get our free guide with 6 ways to grow more fruit in your garden.

Articles and Interviews about Growing Fruit

Here are more resources to help you grow fruit.

Courses on Fruit for Edible Landscapes and Home Gardens

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Guide to Growing Nanking Cherry: An Easy-to-Grow Bush Cherry

Guide to growing Nanking Cherry, an easy-to-grow cherry bush.

By Steven Biggs

Grow Nanking Cherry

The Nanking cherry bush has a spectacular bloom early in the spring.

“Dad, someone’s taking a picture of your garden,” shouts one of the kids. It’s early May, so I know which plant will be in the photo.

The Nanking cherry, a.k.a. Prunus tomentosa. Even though our front garden is a party of spring flowering bulbs, when the Nanking cherry is blooming, it steals the show.

The Nanking cherry bush is like a stop sign. Pedestrians going past our house change gears from a brisk walk to a full stop and then take photos.

Spring isn’t the only time it looks great: it looks great again as the fruit colours up. And unlike cherry trees, where you have to look upwards, this cherry bush is at eye level.

Perfect Fruit for a Home Garden

Nanking cherry is ideal for a home food garden because it’s compact, ornamental, and easy to care for. By comparison, many fruit trees require a fair bit of pruning and pest and disease management. And they take more space.

The small, bright-red cherries are juicy. I’d place the taste somewhere between sweet and sour cherries.

Where to get Nanking Cherry

Nanking cherry flower buds

When I teach about edible landscapes, most students haven’t heard of Nanking cherry because it’s not too common in the horticultural trade. It’s a pity because this is such a fantastic home garden fruit bush.

Look for a nursery specializing in fruit and cold-hardy plants. Or, better yet, find somebody who is already growing it, because many of the seeds that drop around the bush will grow.

(I once mentioned this to my class and was asked by students if that meant I had extras to share. I did. And I took in a tray of small cherry bushes the following class.)

By Seed

While many fruit trees and bushes are propagated commercially by cuttings or grafting, Nanking cherry is commonly seed grown. You can grow them from seed at home:

Look for small Nanking cherry plants growing from seed near a mature, fruit-bearing bush.

When saving seeds to grow, don’t let them dry out too much

In the fall, place seeds in damp potting soil

Store potted seeds in a cold location until spring (a fridge or animal-free shed or garage is fine)

In spring, watch them grow!

When you grow from seed, the seedlings will all be genetically distinct, so expect some variability between plants. Seed-grown plants often flower in less than five years.

Cuttings

If you have a Nanking cherry plant that you really like, you can also propagate it from cuttings. Root softwood cuttings in early summer, as fruit ripens, or root cuttings from dormant hardwood in the spring. High humidity and rooting hormone increase the percentage of cuttings that root.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Layering

Another way to propagate Nanking cherry is by layering. This is the practice where a low-lying branch is covered with soil until it grows roots and can be detached from the main plant. I find it’s often enough to simply to pin a low-lying branch to the soil by covering it with a brick.

Nanking Cherry Varieties

Red-fruited, white-flowered varieties of Nanking cherry are the most common in the horticultural trade.

There are not a lot of improved varieties available commercially. At the time of writing this, I’ve just ordered one called ‘Pink Candles.’

Along with the common seed-grown, white-flowered, red-fruited Nanking cherry varieties, look for:

White-fruited varieties

Pink-flowered varieties (like ‘Pink Candles, above)

Cold-Climate Cherry

If you’re gardening in a cold zone, Nanking cherry withstands cold winters and hot summers. My grandfather grew Nanking cherry in Calgary, a mercurial climate if ever there was one. His cherry bushes soldiered on through snow in summer and balmy winter chinook winds.

(Incidentally, he also made wine from Nanking cherry, although I was too young at the time to partake!)

Cold hardiness is never an exact science as there are many variables. But this is a very cold hardy plant, surviving winter temperatures as low as -40°C (-40°F).

Pick a Location for your Nanking Cherry

Sunlight: Full sun is best. As with many crops, if you only have partial sun, it’s worth a try. You’ll still likely get something.

Soil: Well-drained soil, enriched with compost.

Snow load: Winter snow coverage is, if anything, helpful, as it insulates the bush. I have one next to my driveway, and it’s covered every year with heaps of snow.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Prune Nanking Cherry

One of the things that makes fruit bushes far more suited to home gardens is that the burden of pruning is less. You can prune annually if you want – and you’ll be rewarded with a nicer form and more yield. But if you’re busy and don’t get around to it, that’s fine too.

Timing: Prune in late winter.

Size: Remember, as the gardener, you decide the final height of your Nanking cherry bush. Depending on the growing conditions, it will get to 1.5 – 3 metres high (5 – 10 feet). Bushes can get fairly wide if space permits.

I keep mine pruned to about 1.5 metres (5’) high. That’s because I don’t want it to block the sight line between my garden and the sidewalk. And another important consideration is not to let the bush get any higher than you can pick!

In general, pruning that encourages young branches encourages more fruit. Keeping the canopy open with pruning helps to minimize the chance of any diseases because there is good air circulation. Pruning tips:

Remove some of the older branches

Trim out dead branches

Cut out crossing branches

Prune to shorten the bush

Nanking Cherry Pests and Diseases

Nanking cherry is in the same family as cherries and plums, which are affected by a number of pests and diseases. But I’ve never found the need for pest or disease control.

The one challenge I occasionally encounter is branch dieback where leaves on a branch dry up, and the branch eventually dies. Some sources attribute this to fungal diseases. For dieback, prune affected branches back to the main stem.

Harvesting Nanking Cherries

We eat lots of our Nanking cherries right in the garden! But they are versatile in the kitchen too.

Nanking cherries are an early summer fruit. Around here, that means that I’m picking them around the same time as strawberry season is finishing up.

Unlike sweet and sour cherries, where the stem is left attached to the fruit when picked, the stubby little stems on Nanking cherry stay on the bush. As a result, the fruit don’t last as long as other cherries.

Nanking Cherry in the Kitchen

The kids and I sometimes stand around a bush and guzzle cherries and then see who can spit the seeds the farthest. And that’s an important point I should make: like all cherries, there’s a pit!

Use Nanking cherries for whatever recipes call for sour cherries. I also freeze some for winter use. Because of the size, they are a bit fiddlier to pit than larger cherries.

Here are ways we enjoy using Nanking Cherry:

Nanking cherry juice

Nanking cherry compote

Nanking cherry bump (not for the kids!)

And…one other food related idea: I consider cherry wood the finest wood for smoking meat. So when I prune my Nanking cherry, I keep the branches to use for smoking.

Nanking Cherry FAQ

Do I need more than one Nanking cherry bush?

Many sources report the need for two bushes for cross pollination. I started out with one bush – the only one in the neighbourhood – and had good fruit set. There are reports of some self-fertile varieties.

When should I move my Nanking cherry bush?

The best time to move it is in the spring, while it’s still dormant.

Can I grow my Nanking cherry bush in shade?

It will grow best in full sun, but can grow respectably well in part sun/shade. Just know that you probably won’t get as much fruit as you would if it were growing in a full-sun location. As home gardeners we don’t always have perfect conditions.

Can I grow my Nanking cherry in a wet location?

Well drained soil is best. If the water table is high, consider growing in a raised bed.

What about animal pests eating the Nanking cherries?

The birds will like them just as much as you do. But unlike large tree fruit, such as apples and peaches, there’s much more to share when we grow small-fruited crops such as cherries.

Should I cover my Nanking cherry if there’s a frost?

The flowers are early in the season, when the risk of frost is still high. Most years I still get good fruit set here in Toronto. I’ve had reduced fruit set caused by a freeze once in a dozen years.

Is there a Nanking cherry tree?

Nanking cherry naturally grows as a bush.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Cherries

Find out about 5 Types of Cherry Bush to Grow in Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

Hear Dr. Ieuan Evans talk about the Evan’s Cherry

More on Growing Fruit

These Courses Can Help you Grow Your Own Fruit

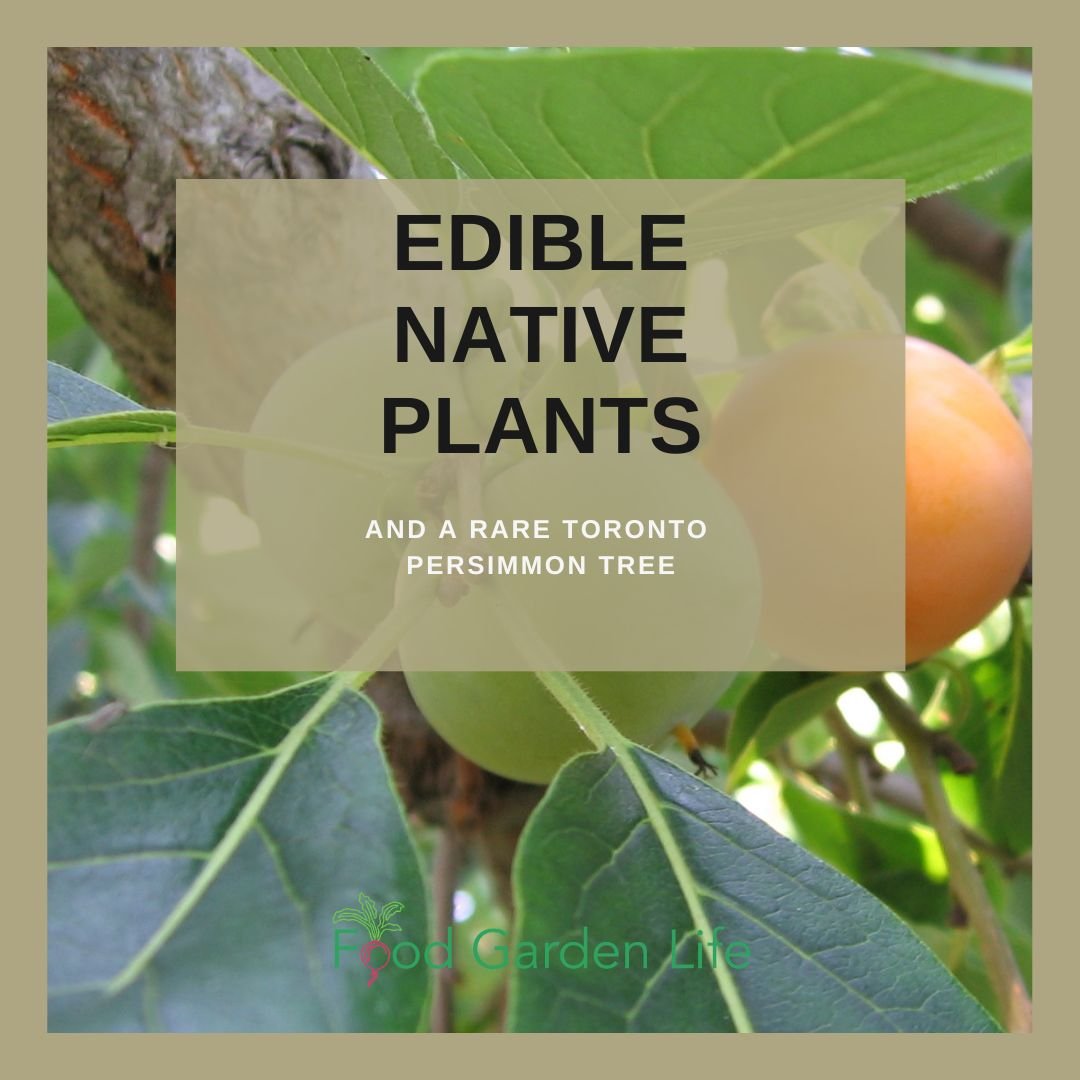

Edible Native Plants...and My Quest for a Rare Toronto Persimmon Tree

Native North American Fruits and Nuts (including persimmon and pawpaw!)

By Steven Biggs

Ontario Native Edible Fruits and Nuts

Pointing to two trees, Tom Atkinson explains that we have the makings of a golf club.

“There you have the shaft of the club; here you have the head,” he says, pointing from one tree to the other:

The shagbark hickory, with a bit of give in the wood, is ideal for the shaft.

The American persimmon, as part of the ebony family, has extremely hard wood that is suitable for whacking the ball.

Both are native North American species; and both have edible parts.

Hunting Pawpaw and Persimmon in Toronto

Our tree trek today is the result of my interest in another North American native, the pawpaw tree.

Because of my fascination with pawpaw, I tracked down Atkinson, a Toronto resident and native-plant expert, whose backyard is packed with pawpaw trees.

After I visited his yard and soaked up some pawpaw wisdom, he mentioned a fine specimen of American persimmon growing here, in Toronto.

I took the bait.

Under a Toronto Persimmon Tree

Now, in the shadow of that persimmon tree, I’m learning far more from Atkinson than persimmon trivia:

The nut of the shagbark hickory, a large native forest tree, is quite sweet.

He points to a pin oak, explaining that the leaves are often yellowish here in Toronto, where such oaks have trouble satisfying their craving for iron.

Waving toward a couple of conifers, Atkinson explains that fir cones point upwards, while Norway spruce cones point down.

There’s stickiness on the bud of American horse chestnuts, but not on their Asian counterparts.

And while the buckeye nut is normally left for squirrels, he’s heard that native North Americans prepared it for human consumption using hot rocks.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

A Backyard Native Fruit Food Forest

In his own garden, Atkinson’s focus is on native trees and shrubs. Many of them are considered Carolinian and are, here in Toronto, at the northern limits of their range.

My own interest in native trees and shrubs has gustatory motivations, but Atkinson’s came about because of his woodworking hobby. “I thought, if I was using wood, I should be putting it back,” he explains. While no longer woodworking, he still has a garden full of native trees and shrubs.

The edible native North American fruit and nut trees in his backyard food forest include sweet crabapple, black walnut, bitternut hickory, red mulberry and beaked hazelnut. “It is really for the creatures of the area, all this bounty,” he adds. I’m taken aback by his generous attitude towards harvest-purloining wildlife, but it’s consistent with his approach of putting something back.

Find out about elderberry, a native fruit bush.

American Persimmon

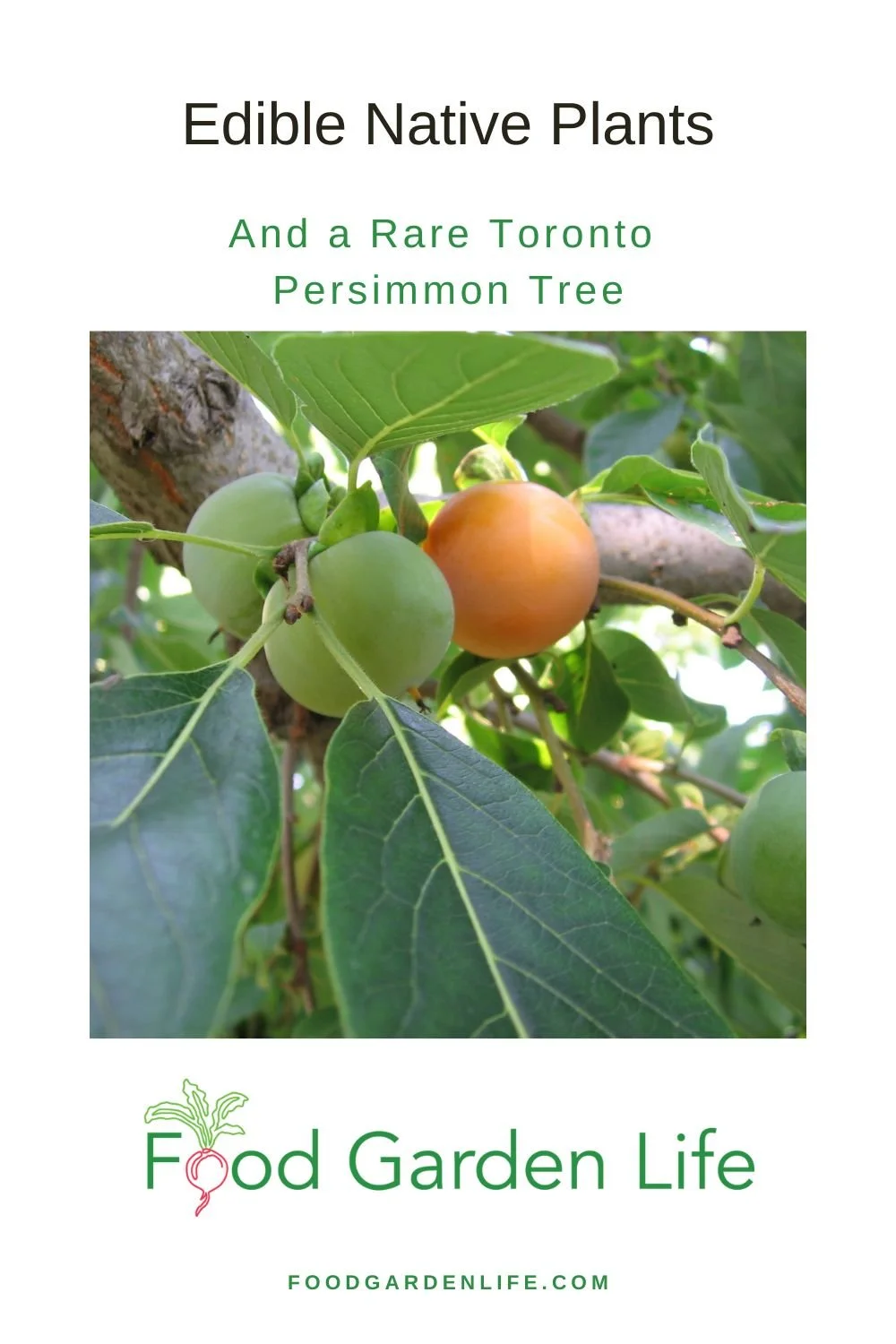

In the shadow of an American persimmon in Toronto. Grow persimmon in the warmer parts of Ontario.

Sitting under the American persimmon tree and looking up, I’m dismayed to find that the fruits are still green. Atkinson cautions that the fruit are astringent and bitter when unripe, so I satisfy myself with snapping pictures.

He explains that although this is a native North American species, it doesn’t usually grow wild this far north. But it grows well under cultivation.

(I found ripe, orange American persimmons a week later at Grimo Nut Nursery in Niagara, where the more temperate climate aids in ripening fruit earlier than in Toronto. They are sweet and velvety on the tongue; I’m delighted that the young persimmon tree I’ve been nurturing in my garden will have been worth the effort when it starts to fruit. And the fruit-laden trees are beautiful.)

Pawpaw

Atkinson's Toronto backyard, where he grows pawpaw trees and other native fruit trees.

Pointing to clusters of mango-like fruit, Atkinson says, “The fragrance of the pawpaw when ripe is aromatic.” He finds that the texture is like custard.

Each fruit usually contains four to eight seeds. “Like a watermelon, spit out the seeds,” Atkinson adds.

Don’t wait too long to pick it. “If it’s starting to turn brown, give it to the squirrels or raccoons,” he advises.

Pawpaws can be found growing wild on the north shore of Lake Erie into the Niagara region. Like the American persimmon, you’re not likely to find wild ones here in Toronto, but they do grow well here when planted. The large, lush leaves add a tropical feel to the garden.

Serviceberry

Serviceberry is a native edible plant well suited to growing in the city.

When it comes to native edible plants, Atkinson believes that one of the best to grow in the city is the serviceberry.

“There’s a whole bunch of them,” he explains, listing the related members of the serviceberry (Amelanchier) clan. They all have in common an edible fruit similar in size to a blueberry.

Palatability varies by species and variety. The saskatoon berry, which is also grown commercially, has consistently good fruit quality, according to Atkinson.

Serviceberry is widely planted in Toronto parks and is common in the nursery trade. They can be grown as a small tree or a bush.

In my own garden, I end up sharing my serviceberry harvest with robins if I don’t pick them quickly enough. Atkinson says that cedar waxwings like them, too.

Aside from the fruit, the serviceberry leaves turn a vibrant orange-red in the fall and the bark, smooth and grey, is showy, too.

Here’s a member of the serviceberry family that’s grown as a commercial crop: Guide to Growing Saskatoon Berries: Planting, Pruning, Care

American Hazelnut

American hazelnut is a native nut bush. It’s related to the European hazelnuts sold in grocery stores, but the nuts are smaller.

Hazelnuts send out attractive catkins in late winter, before any leaves are out.

Crabapple

“They’re a delight to look at,” agrees Atkinson as we change gears and talk about the sweet crab, a wild crabapple. “It puts on a really good show of flowers,” he says as he describes a blush of pink on white flowers in the spring, adding, “It’s as good as a flowering dogwood but in a different sort of way.” The fruit is very waxy, and very attractive, having a greenish yellow colour.

“Squirrels don’t touch it,” he exclaims. He likes the fall leaf colours, which range from yellow to burnt orange.

On the culinary side, he says the sweet crab fruit is sour, but a perfect accompaniment when roasted with a rich meat such as pork, where the tartness of the fruit cuts the richness of the meat.

Black Walnut

Atkinson speaks warmly of towering black walnut trees and of the beautiful dark wood they yield. He notes how common they are in the Niagara peninsula: “They’re almost like weeds.”

I agree with the weedy bit: My neighbour’s black walnut stops me from growing anything in the tomato family at the back of my yard. Despite its hostile actions towards my tomatoes, I have grown fond of sitting under that tree, never really considering why. “The shade under a walnut is really quite lovely,” he says, describing dappled light that results from the long leaf stalks adorned with small leaflets.

He discourages me from promoting the black walnut for edible uses because the nut meat is very difficult to extract: the shells are rock hard, requiring a hammer to crack. And the meat doesn’t come out easily like an English walnut, but has to be picked out. But by this point I’ve already decided to write about edible native plants because of their ornamental appeal.

Read about wicking beds, a way to deal with black walnut toxicity, a.k.a. juglone.

Growing Native Fruit in Urban Areas

I thank Atkinson for the tour and email correspondence. A couple of weeks later, Atkinson emails me a photo of a broken pawpaw branch. He writes: “Steve, here is what befalls a pawpaw when in an urban setting, and there are hungry raccoons about. I do not begrudge my masked friends at all for doing what inevitably they will do when after pawpaws.”

FAQ American Persimmon

Can persimmon grow in Ontario? Can you grow persimmons in Canada?

American persimmon is reported to be hardy into Canadian hardiness zone 4, though a long growing season with summer heat is needed for fruit ripening. Best in zones zones 5b-8.

Remember: Zones are only a guideline. Sometimes you can cheat if you have a warm microclimate.

Can I grow a persimmon tree from seed?

If you grow American persimmon from seed, the main thing to remember is that they are “dioecious.” This just means that a plant can be male or female. If you grow a seed and get a male plant, you won’t get fruit from it.

Many commercial varieties produce fruit without a male.

Interested in Forest Gardens?

Here are interviews with forest garden experts.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More Information on Growing Fruit

Articles and Interviews about Growing Fruit

Courses on Fruit for Edible Landscapes and Home Gardens

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Guide: How to Grow Sorrel (& How to Use it!)

Find out how to grow sorrel, and get ideas for creative sorrel recipes.

By Steven Biggs

Planting Sorrel: An Easy-to-Grow Perennial Vegetable

Sorrel is one of my favourite crops because it checks off a number of important things for me:

It’s easy to grow (it’s a perennial that comes back year after year)

It’s difficult to find fresh sorrel leaves in stores (and if you find them, they’re expensive)

It is versatile in the kitchen (soups, meat, salads, and more)

(And I've cooked with sorrel on TV!)

Sorrel also has a rich herbal history, with a variety of uses.

I’m no herbalist, so in this post I’ll tell you how to grow sorrel and give you lots of ideas for using it in the kitchen.

Haven’t Seen a Sorrel Plant? You’re Not Alone!

Garden sorrel is a hardy perennial.

Sorrel is a familiar ingredient in European cuisine. That’s how it came to North America—with European settlers.

The “wild” sorrel sought after by foragers is simply sorrel that’s escaped cultivation.

Yet many people in North America don’t know to sorrel.

If you’re new to sorrel, it’s grown for its leaves. It’s sour leaves. I think of it as a lemon substitute for northern gardeners.

When I shop at eastern European shops, I see jarred sorrel…horrid sludge. I don’t recommend it. Grow yourself fresh sorrel!

Grow your own sorrel, and skip the brined sorrel!

But it was an eastern European connection that go me growing sorrel. As a teen, I took Ukrainian lessons (hoping to learn my mom’s first language—which she never taught us.) I never did pick up the language—but the teacher, who knew I was a gardener, couldn’t believe I’d never heard of sorrel. And brought me a clump of this plant that she said was an essential ingredient in the old country.

What is Sorrel?

Sorrel is a hardy perennial plant that grows in a clump. It’s tough as nails, hardy into Canadian zone 4.

The long, narrow leaves are ready to pick early in the season, making it one of the first greens to harvest.

You can use the leaves fresh—or cook with them. (See How to Use Sorrel, below.)

Types of Sorrel

There’s more than one type of sorrel. Here are three common ones:

Garden sorrel leaves can be over 30 cm long when plants are in moist, rich soil.

Garden Sorrel (Rumex acetosa). Garden sorrel was brought to north America by European settlers. It's grown in gardens, but is also an escapee that can be found growing wild. Leaves reach 30-60 cm (12-24 inches) long, depending on the growing conditions.

Sheep Sorrel (R. acetosella). Sheep sorrel is another escapee. Sometimes called sourgrass. You might find it filling in exposed spots like vacant lots and roadsides. Seed stalks take on a reddish colour. Spreads by seed and running roots. This is the less-loved cousin to garden sorrel, with smaller, narrower leaves that have a distinct lobe at the base, a bit like an arrowhead. I wouldn’t plant this fast-spreading plant in the garden, but it’s an excellent edible, and popular with foragers.

French Sorrel (R. scutatus). French sorrel is also called round-leaved sorrel. The leaves are shield shaped. Plants are shorter than garden and sheep sorrel.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

How Sorrel Grows

Sorrel grows best in rich, moist soil, in full sun or partial shade. Though that doesn’t mean it won’t grow elsewhere…as evidenced by the behaviour of sheep sorrel in vacant lots!

But in a garden setting, give it water if it’s in a dry location. If it’s in partial shade, you won’t need to water as much.

Flower stalks turn into red-tinged seed spikes. Remove stalks to encourage young leaves—unless you want to collect sorrel seed. If you’ve been diligently removing flower stalks, you’ll be able to continue harvesting for the whole growing season, until the plant shuts down for winter—when the top dies back with fall frosts.

Where to Grow Sorrel Plants

Because sorrel is ready to harvest early, I like to have mine close to the kitchen.

Growing Sorrel in Perennial Borders

As a perennial plant, sorrel is at home in the perennial border. Stick it at the front so it’s easy to reach.

Sorrel in the Vegetable Patch

A row of garden sorrel with seed heads. See the red tinge?

I don’t plant sorrel in my main veggie patch, where I move around crops from year to year. Because it is a perennial plant, I grow sorrel around the periphery, with the rhubarb and asparagus—other perennial vegetables.

I’ve seen an entire row of sorrel plants used as a border in a formal edible garden.

Find out more about perennial vegetables.

Sorrel in the Herb Garden

Garden sorrel and French sorrel are well behaved plants that make a nice addition to a herb garden.

Looking for vegetable garden planning ideas? Here are articles to help you plan and design your vegetable garden.

How to Harvest Sorrel

Young sorrel leaves in the spring are the most tender.

You’ll get the best flavour and texture in spring, from young leaves.

But you can harvest sorrel until fall frosts shut the plant down for winter.

How to Propagate Sorrel

There are two ways to propagate sorrel plants.

Division. When a clump is big enough, divide it in the spring.

Seed. Sow sorrel seeds indoors in early spring. Move to the garden after the risk of frost has passed. Space plants about 30 cm (1 foot) apart in the garden.

FAQ: Sorrel Plants

Will Sorrel Grow in Shade?

Sorrel grows in full sun and partial shade. Because it produces larger, more tender leaves in moist soil, semi-shaded conditions are a good option where conditions are hot.

Are sorrel and hibiscus the same?

An unrelated plant, Hibiscus sabdariffa, also goes by the name sorrel. It’s tangy flowers are used in Caribbean cuisine.

Can I forage for sorrel?

In North America, both garden sorrel and sheep sorrel grow wild.

If you’re interested in foraging, listen to our chat with foraging expert Robert Henderson.

What are oxalates?

Wood sorrel is of no relation to garden sorrel, but it, too, has a sour tasting leaf.

Sorrel contains oxalic acid, a compound also found in spinach and rhubarb. If you go overboard and eat too much, it can cause tummy upset. That means don’t be a pig. You wouldn’t eat a whole bowl of lemons, would you? Consume it with other foods. It’s for flavour—not the main course.

One other thing about oxalic acid is that it can provoke existing joint and kidney problems. So if you have a history of kidney stones, skip the sorrel

What about wood sorrel?

Related in name only, wood sorrels (Oxalis sp.) can be grazed too.

Bloody dock is also known as red-veined sorrel.

Is bloody dock a sorrel?

Bloody dock, R. Sanguineus, is also known as red-veined sorrel. It’s related to sheep, garden, and French sorrel.

But don’t waste a second on it. Unless it’s as an ornamental. (It's quite beautiful.) You’ll find shoe leather that’s more tender than bloody dock leaves.

How to Use Sorrel

Before we get to using sorrel in the kitchen, enjoy sorrel while you’re in the garden. You can graze as you garden. The tangy leaves are refreshing.

Because sorrel is tangy, it pairs well with rich food.

Here are ways to use sorrel:

Use sorrel leaves in salads (I find a sorrel-only salad a bit too tangy, so I mix it with other greens)

Sorrel leaves in sandwiches

Sorrel soup (see recipes below)

In recipes that call for greens such as spinach or lambs quarters, substitute part or all of the greens with sorrel (I add it to my Swiss-chard-and-leek spanakopita)

Add it to sauces for a lemony flavour (I throw in pieces of sorrel leaf when braising meat)

Add sorrel leaf bits to an omelette or frittata

Chop and freeze for use through the winter

I’ve seen a recipe for devilled eggs that includes bacon and sorrel…sounds divine

Gourmet butter: Finely chop sorrel leaves and mix in with soft butter

Making a ranch-style sour-cream or yogurt dip? Add chopped sorrel

Make ordinary pesto shine by adding a bit of sorrel (oh yeah, pairs nicely with blue cheese!)

Sorrel Recipes

Sorrel Soup

Pin this post!

Here’s an easy-to-make sorrel soup recipe.

Ingredients

3 tbsp. butter

1 onion, chopped

3 potatoes, cubed

3 cups sorrel leaves, stem removed

8 cups broth

½ cup sour cream

Salt and pepper to taste

Directions

Fry onion in butter until golden

Add potato, sorrel, broth and simmer (covered) for about 15 minutes, until potatoes are soft

Puree (I use a hand immersion blender)

Whisk in sour cream

Heat to serve (don’t boil)

Sorrel Vichyssoise Soup

If you want to take sorrel soup to the next level—and use some of your homegrown leeks—this take on the creamy potato-leek classic is delicious.

Sorrel vichyssoise soup, topped with a sorrel leaf, a dollop of sour cream, and edible redbud flowers.

Ingredients

2 tbsp. butter

3 cups of sorrel leaves, stem removed

1 large leek, chopped (use both white and pale green parts)

1 onion, chopped

3-4 potatoes, cubed

4 cups water or broth

2 tbsp. salt

4 cups whole milk (use cream if you want something more decadent)

Directions

Fry leek and onion in butter until onion is golden

Add potato, salt, water/broth, sorrel and bring to a boil

Simmer until potatoes are tender

Stir in milk, and then puree

Serve chilled

When serving, I like to float a dollop of sour cream on top, alongside a raft of croutons.

Sorrel Paste and Sorrel Soup

Hear this interview with forager Robert Henderson, who talks about how to make sorrel paste and sorrel soup.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Courses

Edible Garden Makeover. Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

Container Vegetable Gardening Masterclass. Here’s a course that gives you everything you need to know for container vegetable gardening success.

Vegetables to Grow: 12 Tips to Choose What’s Best for Your Vegetable Garden

Choose the best vegetables to grow in your garden with these 12 crop-choosing tips.

by Steven Biggs

Choose Which Veggies to Grow in a Garden

12 tips to help you choose vegetables to grow.

“Grow radishes!”

It’s a recommendation I often hear given to new gardeners. That’s because radishes are easy to grow. And they grow quickly.

True.

But in my house, it’s the radishes that are still on the veggie platter when everything else has been devoured.

So while the easy-to-grow crops are part of a good vegetable garden plan, there are other things to think about too.

Keep reading to find out how to pick vegetable crops and varieties for your needs and situation. Instead of being prescriptive and telling you what you should grow, this post gives you 12 tips to help you choose which vegetables to grow.

1. Grow What You Love

So back to the radishes, there’s no point growing what you won’t eat—even if it’s easy to grow

Even if it’s nutritious.

Grow things you’ll enjoy eating.

2. Grow for How You Cook

I love big slabs of eggplant that I can marinate and grill, so I grow large-fruited eggplant varieties

As you choose crops and varieties, think about how you’ll use your harvest.

Here’s an example:

I love big slabs of eggplant that I can marinate and grill—or use to make eggplant parmesan. So I always go for large-fruited eggplant varieties

For tomatoes, I like to make sauce all winter, so I grow good sauce-making varieties

3. Rule Out Some Crops

There might be crops that aren’t a fit for your garden. I’m talking about space hogs—and crops that will probably be a frustration.

Space Hogs

Some crops use up a lot of space—more than makes sense in a small garden.

For example:

I love Brussels sprouts. But they’re big plants that tie up the same patch of garden for an entire season. So I leave them to the market gardeners.

I love edamame too. But for the amount I get considering the amount of space they take in the garden, they’re not my top choice.

Unnecessary Frustrations

Depending on what your situation, there might be crops that disappoint—or frustrate—you.

Here’s are examples:

Corn. I love corn. So do all the raccoons around here. So I don’t grow it. I don’t need the chest pains!

Tomatoes. Some people prefer cherry tomatoes to big beefsteak tomatoes because that way there’s lots more tomatoes to harvest. That way, the gardener gets lots even if wildlife steals some.

4. Try Something New

Have you added something new to your garden? I like to grow something new every year.

Recently it was celtuce, a.k.a. stem lettuce. It’s easy to grow and fun to cook with. Not a new crop at all…just new to me.

20 years ago I grew cucamelons for the first time and have grown them ever since.

20 years ago I tried cucamelons and have loved them and grown them every year since.

Look for neat varieties (e.g. a pepper variety I love is the corkscrew-shaped ‘Corbacci’

Or branch out into a crop from a cuisine you’re not familiar with (okra was new to me…but after I learnt a Cajun fiddle tune I wanted to learn how to make Cajun-style gumbo soup…and now I aways grow okra for making gumbo soup!)

5. Consider Diseases

Variety choice sometimes helps with disease problems. For example:

Downy mildew ravaged my basil for a couple of years. So now when I’m getting basil seeds, I look for mildew-resistant basil varieties

There’s no totally blight-proof tomatoes, but there are blight-resistant varieties, worth adding to the mix in a garden so that in years when blight decimates the tomato patch, there are still a few plants producing late in the season

6. Pick Crops for Small Spaces

If space is a challenge, crop choice can often help you harvest much, much more.

Crops for Vertical Gardening

If you’re gardening in a small space, choose vegetable crops that you can grow upwards on trellises, tee-pees, or fences.

If you’re gardening in a small space, choose veg that you can grow vertically. When you grow upwards, that frees up space on the ground—so you can fit more into a small space.

Here are a couple of my favourites:

Runner beans. I love runner runner beans! The flowers are edible, great for bouquets, attract hummingbirds. Oh, did I mention there’s beans too! (If you’re in a maritime climate, you might find runner beans produce more than pole beans.)

Zucchini: Many zucchini varieties have a bush-like growth habit, and the plant can take up a fair bit of space. But if you grow a climbing zucchini variety, it won’t take up as much space…so there’s room to plant more in your garden.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Plants with Multiple Edible Parts

You might also think about plants with more than one edible part, so in a limited space you’re getting multiple harvests from one crop

Radishes have edible seed pods.

Snap peas (you can eat the peas and the pod…and don’t forget young tendrils)

Squash (eat the flowers, the squash…and shoot tips!)

Beets (both leaves and roots are edible)

Radish (along with the roots, the seed pods are edible)

Find out more crops with more than one edible part.

Hear a chef talk about using squash shoot tips and other uncommon ingredients.

7. Choose for an Early Harvest

Look for crops and varieties that can move up your first harvest.

For example:

I like broad beans, which can be planted far ahead of all the other types of beans

Look for fast-maturing varieties (I grow fast-maturing arugula and spinach varieties in my cold frames in late winter because I want that first harvest as soon as possible)

Do the same with your beets, carrots, tomatoes and other crops

To choose faster-maturing varieties, compare the days-to-maturity information with other varieties (often called “DTM”)

8. Remember Fall Harvesting

Parsley holds up well when fall frosts arrive.

Remember to add in cool-season crops that keep producing as fall frosts arrive.

Cabbage family

Kale

Celery

Parsley

9. Choose for a Short Growing Season

If you’re dealing with a short growing season, there might be some crops you don’t want to bother with. I have friends who won’t grow eggplant and pepper.

More ideas:

Bush beans give a quicker, more concentrated harvest than pole and runner beans

Look for varieties that mature more quickly (e.g. we love Cream of Saskatchewan watermelon, which ripens melons much more quickly than watermelon varieties grown in warmer zones.)

10. Grow for Year-Round Enjoyment

Many gardeners like to enjoy the harvest year-round. If that’s you, here are some ideas:

· Grow dry beans that you can easily store for later use

· Look for root crops that store well (these tend to be varieties that grow larger roots)

· Thought of kohlrabi…there’s a storage variety too

· You can harvest leeks right through the winter when there’s a thaw

Get more crop ideas for year-round enjoyment.

11. Plan an Edible Landscape

Looking for attractive veg to add an ornamental touch to a landscape?

Here are ideas:

Asparagus looks great at the back of a perennial border, with its tall, ferny foliage

Runner beans have beautiful flowers

Lovage is a perennial with a celery-like taste, great for the perennial border

Eggplant has beautiful flowers

Kale is a great way to add colour and texture into a garden

Here are more perennial edibles.

If you’re serious about edible landscaping and want to create an awesome out-of-the box edible landscape, check out this course.

12. Crop Substitution for Less Work

Pin this post!

Keep your workload to a minimum through crop choice!

Here are examples of the type of thinking you can use to make less work for yourself.

Leaf celery instead of stalk celery. Stalk celery takes lots of water and feeding to get tender, crispy stalks. Leaf celery doesn’t make big stalks—you just get lots of leaves on short stems, and it’s far less bother if you don’t mind consuming celery this way. (I chop it into soups, stews, and salads for that same celery taste.)

Ground cherry instead of cape gooseberry. I actually prefer the taste of cape gooseberries…but they need a longer growing season, meaning I have to start the seeds earlier, and then give them prime, hot, garden real estate to get a decent harvest. Ground cherries are far easier to grow. (Find out more about these two different husk cherries.)

Broccoli instead of cauliflower. Not only is cauliflower more finicky, to get snow-white heads it must be blanched, which is often done by tying leaves over the head with an elastic. It’s a lot of bother compared to broccoli, which requires no blanching.

Squash instead of potato and sweet potato. Squash is far less work. Instead of transplanting sweet potato plants, you just poke squash seeds into the soil. And instead of digging out sweet potato roots, you just snip squash from the vine. You still get the sweet, orange ingredient for baking.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Vegetable Garden Planning

More on Growing Vegetables

Vegetable Gardening Articles and Interviews

For more posts about how to grow vegetables and kitchen garden design, head over to the vegetable gardening home page.

Vegetable Gardening Courses

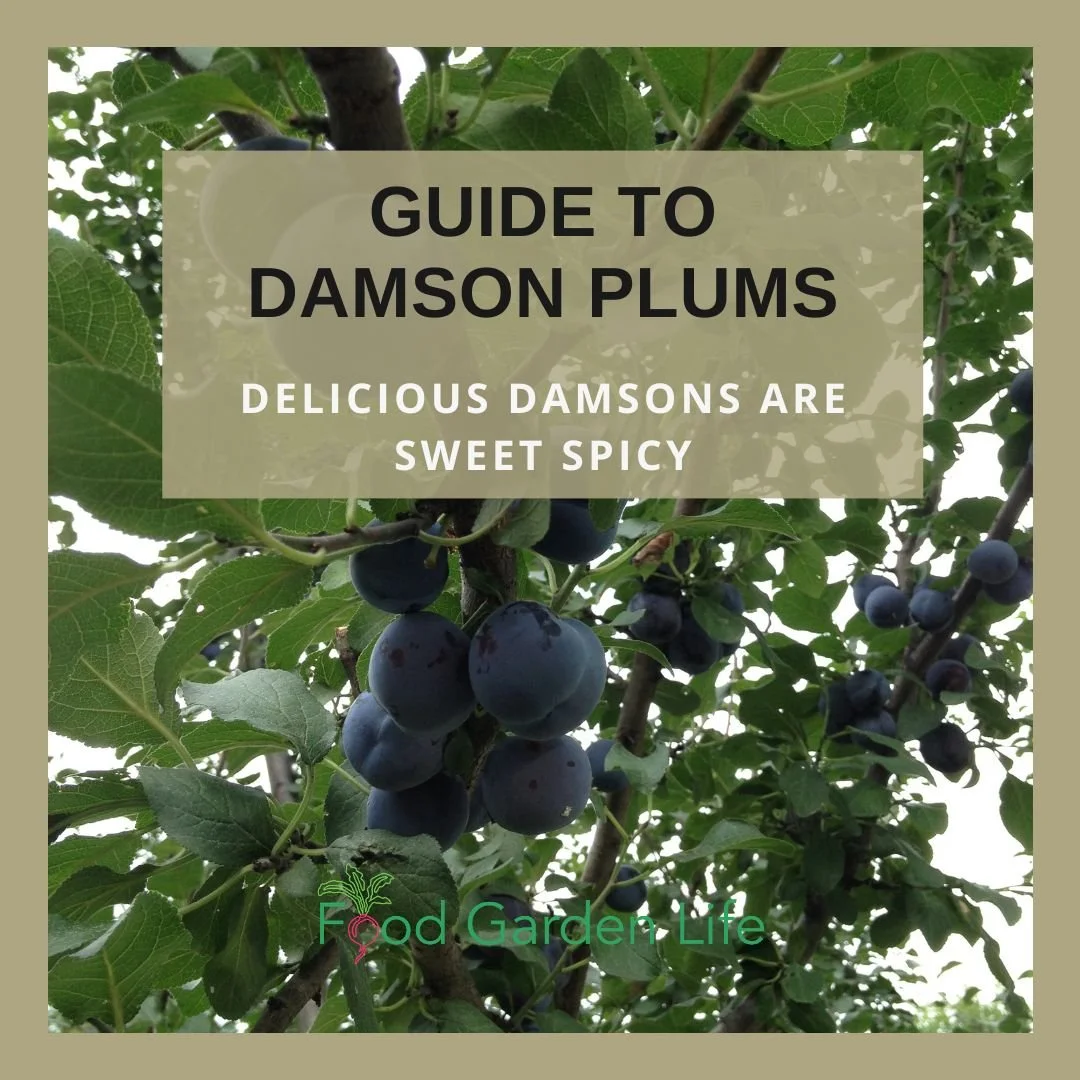

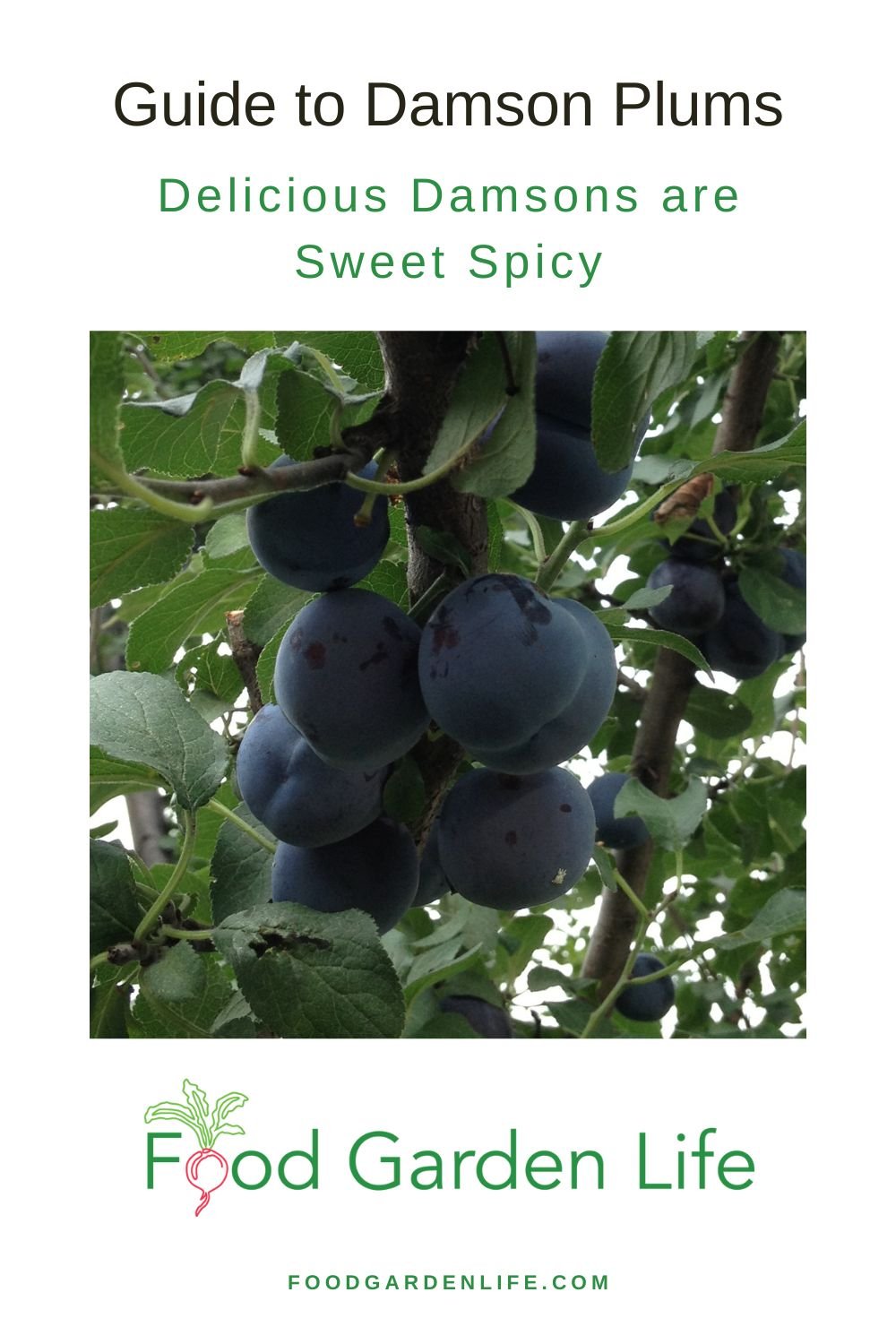

Damson Plums: This Forgotten Fruit Combines Dry, Sweet, Spicy, and Bitter (and it’s a perfect home-garden crop)

Find out how to grow this forgotten fruit that has a rich, complex flavour. It’s a gem in the kitchen, and easy to grow in a home garden.

By Steven Biggs

Disappearing Damsons

I remember when Nana started to ration the jam. The damson jam.

She was running low on her homemade damson jam. And what was left was reserved for damson tarts—one of her specialties.

She couldn’t get damsons any more.

Why the fuss? Because damsons have a special flavour and make marvellous jam. They’re the ultimate plum for cooking, with a rich, complex flavour that combines sweet, spicy, slightly sour, and a touch of bitter.

I was just a kid at the time. Since then, I’ve rarely seen damson fruit or damson trees for sale. Too bad, because it’s a unique fruit that’s well worth a place in a home garden.

But they’re not completely forgotten.

When I drove through the Kamouraska region of Quebec, I took a detour especially to visit Maison de la Prune, a small damson orchard and museum in what was once a major damson production area. I came home with damson syrup, and sweet and savoury jellies.

Keep reading to find out more about this special plum, and how to successfully grow it.

Hear a Damson Expert Explain What’s Special About Damsons

What is a Damson Plum?

Damsons (Prunus insititia) are smaller and not as sweet as their cousin the European plum (Prunus domestica). (Quick plum primer…it’s a big family, including Japanese plums, P. salicina, North American plums, P. americana, and the cherry plum, P. cerasifera.)

A damson is a small, oval-shaped plum. The skin is often a deep blue-purple colour, with yellow flesh, although there are also yellow-skinned varieties. They’re a “clingstone” fruit, meaning that the flesh, which is quite firm, is attached to the stone. Like many fruit in the plum family, the fruit has a waxy “bloom” on it, giving fresh damsons a silvery hue.

Damsons are self-fertile—meaning only one tree is needed to get fruit. They bloom in early spring, with fruit starting to ripen in late summer.

How are Damsons Different From Other Plums?

The damson is smaller than the European plum. These damsons will ripen to a purple colour.

When it comes to the plant itself, the trees have a more compact growth than other domestic plums, developing a gnarled shapes as they get older.

The fruit is smaller too, with more stone and less fruit than other domestic plums—up to one third stone. The fruit is also drier than European plums and Japanese plums.

While damsons are sweet, they’re also slightly astringent, giving them a complex flavour and making them superb for cooking. (Perhaps less attractive for fresh eating, though I love them.)

Along with the astringency comes a spiciness and sweetness that sets them apart from domestic plums.

What is a Bullace?

It’s worth noting a couple of other relatives that are sometimes included when talking about damsons. Along with damsons, Prunus insititia includes bullaces, and St. Julian plums.

St. Julian plum is mostly grown as a rootstock for grafting damsons

The round bullace fruit is smaller than damsons, ripening later, and has a less complex flavour

The bullace is different from the sloe (Prunus spinosa) which is bushier. If the sloe is new to you, look up sloe gin. (I know of sloes because my dad had a bottle of sloe gin when I was growing up.)

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

How to Grow Damsons

Planting Damsons

The first thing to know is that damsons are self-fertile. This means that you can plant one damson tree and get fruit.

Like other fruit that flower early—while there’s still a risk of frost—choose a location where there’s less chance of flowers getting hit by frost. This means:

Avoid low-lying pockets that get heavy frost when other parts of your garden don’t

If you’re in an area with late spring frosts, a north-west-facing slope can be safer than a south-facing slope (it might seem counter-intuitive…but they’ll bloom earlier on a south-facing slope, meaning more chance of frost damage)

Hear a fruit expert talk about site selection in cold climates.

Where to Plant a Damson Tree

Full sun is best for damsons. They tolerate semi-shade if that’s all you have.

Damsons grow in a wide range of soil types. Avoid acidic soils and soils that dry quickly—meaning sandy soils.

Stake newly planted trees for a year to prevent shifting.

Spacing When Planting Damsons

Damsons are a relatively small tree.

Here are a couple of considerations when deciding on spacing between damson trees:

With grafted trees, the tree size and optimal spacing depends on the rootstock

Space between trees allows air flow, which helps reduce disease pressure

In a home garden setting, there are often competing needs for a small space. In that case, you might want to be creative with spacing. For example:

Plant more than one damson tree in a hole – a clump of damsons

How to Care for Damson Plums

Below is more information about how to care for damsons. But to sum it up quickly in case you’re already a fruit grower: Treat damsons as you would other plums.

How to Prune Damson Plum Trees

Damson fruit in mid summer. They have a golden-yellow flesh when ripe.

If you’re growing damsons in a hedge, you might take a hands-off approach to pruning.

When you’re growing damsons as separate trees, use pruning to shape the tree into a framework of branches that gives good strength, and allows air circulation and ease of picking.

A tree from a nursery might already have a framework developed. If it’s a young tree, you can develop the framework of branches yourself. Damsons can be formed into central-leader style trees, vase-shaped trees, or into a bush. For a bush, picture a short trunk, with branches coming out above that.

Pruning fruit trees is an entire article unto itself, but here are top tips:

Avoid narrow, v-shaped angles

Don’t make sloppy cuts that leave a nub of branch beyond a bud

Remove crossing branches

Aim to keep the canopy of the tree open, to allow air movement

Like other stone fruit, damsons don’t respond well to attempts to train them into cordons.

Prune in late winter.

Protecting Damson Blossoms from Frost

With a well-chosen site you’re less likely to have frost damage in the spring…but if there is a late frost, and if your damson tree is small enough, a simple cover might protect the blossoms.

Drape the plant with burlap or horticultural fleece. (I’ve even covered tender plants with an old shower curtain!)

Damson Hardiness

Damsons are very cold hardy. There’s no question of hardiness here in my Toronto garden.

I’ve seen Canadian nurseries listing damson varieties hardy into Canadian Plant Hardiness Zone 3, and American nurseries suggesting USDA Zone 5. Here’s a list of nurseries that sell fruit trees.

Consider zones a general guide. Conditions within a zone can vary—and microclimates allow gardeners to push zone boundaries. There can be “frost pockets” in low-lying areas, and moderate areas near large bodies of water.

With grafted plants, hardiness depends on how hardy the top (scion) is—and how hardy the bottom (rootstock) is.

How to Propagate Damson Plums

Damson Seeds and Suckers

In times past, damsons were commercially propagated using seeds and suckers.

Seeds. When grown from seed, many damson varieties “come true,” meaning the new plant is like the parent. If you want to seed-grow damsons, first stratify the seed, and then sow in a pot or directly in the garden.

Suckers. Suckers are the shoots that come from the base of a mature plant, and already have roots. This is an easy way to get started if you know that the tree is not grafted. (If it’s a grafted tree, a sucker might actually be coming from the rootstock.)

Grafting Damsons

Most commercially produced damsons are propagated by grafting.

Under some conditions, damson trees can grow up to 6 metres (20’) tall. But if conditions are not as good—or if trees are grafted onto a rootstock that restricts growth—they’ll be smaller.

This means that it’s good to know how rootstock can affect damson tree size.

Here are common damson rootstock:

Large. Myrobalan B, Brompton

Medium. St Julian A

Small. Pixy, VVA-1

Damson Harvest

Pick damsons as they develop colour and as the fruit becomes softer to the touch.

Damsons ripen in late summer and early fall.

When are Damson Plums Ripe?

Pick as the damsons become soft to the touch. (You can pick them earlier if making gin.)

Why Damsons Sometimes Fruit Every Second Year

It’s common to have what’s called “alternate bearing,” meaning a large crop one year, and then very little—or nothing—the next. This happens because when a fruit tree carries a heavy crop, energy goes to the ripening of that crop—and flower buds are not formed for the next year.

You can prevent alternate bearing by thinning fruit.

Damson Pests and Diseases

Black knot disease.

Mice and rabbits often gnaw on fruit tree bark over the winter. While damson trees are young, use a spiral tree guard around the trunk for the first few winters to protect the bark from rodents.

Black knot is a fungal disease that affects many plants in the plum family, including damsons. Some damson varieties have more black-knot resistance than others. You can recognize black knot by the black, woody growth encircling a branch. (My kids called it poo on a stick when they were little.)

If you see black knot, prune the affected branch back at least 20 cm (8”) below the knot. Don’t leave the pruned-off branch near your damson trees because the knot provides inoculum for more infection.

Damson Recipes

I started off by telling you about my Nana’s damson plum jam. It was so delicious because of the balance that the damsons give, with the combination of fruitiness, sweetness, spiciness, tartness, and a little bit of astringency. Damsons are excellent for jams, fruit butters, and for making fruit cheese because they contain a lot of pectin.

Because they’re “clingstone,” the fruit is usually separated from the stone after cooking.

There are many more ways to use damsons. You’re more likely to come across these in the UK, where there’s a longer tradition of cooking with them.

Damson chutney

Pickled whole damsons

Damson vinegar

Damson gin

Use them where you would use other tart fruits. And think of using them with savoury dishes—not just sweet. That’s because the combined tartness and astringency work well with rich dishes.

(And if you don’t have the time or inclination to spend a lot of time in the kitchen, stewed damsons are a true delight. When I lived in the UK there were damsons in a nearby hedgerow. I’d stew them, cooking with a bit of water and sugar until soft enough to the damson stones. Then I’d eat them with clotted cream.)

For more recipe ideas, I recommend the book Damsons: An Ancient Fruit in the Modern Kitchen.

Where to Buy a Damson Plum Tree

While you might not see damsons at garden centres, specialist fruit tree nurseries often carry them. If ordering online, look for bare-root trees so shipping costs are lower.

Here’s a list of fruit tree nurseries.

The choice of damson varieties in North America tends to be limited. I’ve most often seen damsons sold as Blue Damson.

(You sometimes see them sold as “Damas Bleu,” as there’s also a long history of damson production in Quebec. If you want to delve into that, here’s a fun book: Les Fruits du Québec: Histoire et traditions des douceurs de la table, by Paul-Louis Martin, who is the proprietor of Maison de la Prune that I mentioned earlier.)

In the UK there is a wider selection of damson varieties. I have a 1926 text that lists Blue Prolific, Bradley’s King, Farleigh Prolific, Quetsche, Rivers’ Early, Shropshire Prune, Merryweather. If you search UK nurseries, you’ll see many of these are still available.

Using Damson Trees in Garden Design

Damsons are good choice for a home garden because they are self-fertile. That means that in a small space, you only need one tree to get fruit.

Here are ideas for using damson trees in garden design.

Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

Damsons work well in edible landscapes with a mixed planting of edibles, and in a food-forest setting. Like many fruit trees, they do best in full sun, but tolerate the sort of partial shade that you can get in an urban edible landscape or on the periphery of a food forest.

Home Orchard or Stand-Alone Specimens

A more traditional planting gives each tree enough space to fully develop. The amount of space needed for well developed, well-spaced damson trees depends on the rootstock.

Hedges and Hedgerows

In my own garden, my damsons are part of a fruiting hedge. There are damson and other plum trees in a long row, underplanted with currants and gooseberries. At ground level are strawberries. It’s still rather neat and tidy, but damsons could work well in a less formal hedgerow or windbreak too, mixed with other small fruit.

Here’s a chat with a small fruit specialist to get ideas for less common fruit for a hedge.

FAQ: Damson Plums

How long should I stake a damson tree?

Remove stakes after the damson tree is established and has rooted into the surrounding soil, usually after one season.

Why are so many fruit dropping off in early summer?

There’s a natural fruit drop in early summer. As long as there are lots of fruit remaining on the tree, everything is probably OK.

Do damson trees fruit every year?

Not always. If there’s a heavy crop one year, there might not be a crop the following year. This is called alternate bearing. You can thin fruit to reduce alternate bearing.

What is the botanical name for damsons? Why am I seeing two different botanical names for damsons?

Good question. You might find damsons as Prunus insititia or as Prunus domestica subsp. insititia. That’s because plant taxonomists sometimes rename things.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Fruit Crops

Articles: Grow Fruit

Visit the Grow Fruit home page for more articles about growing fruit.

Here are a few popular articles:

Courses: Grow Fruit

Here are self-paced online courses to help you grow fruit in your home garden.

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Grow Microgreens at Home for Easy-to-Grow Salad Greens all Year

How to grow microgreens indoors. The setup is simple. The materials are easy to get. There’s no need for fancy lights or equipment.

By Steven Biggs

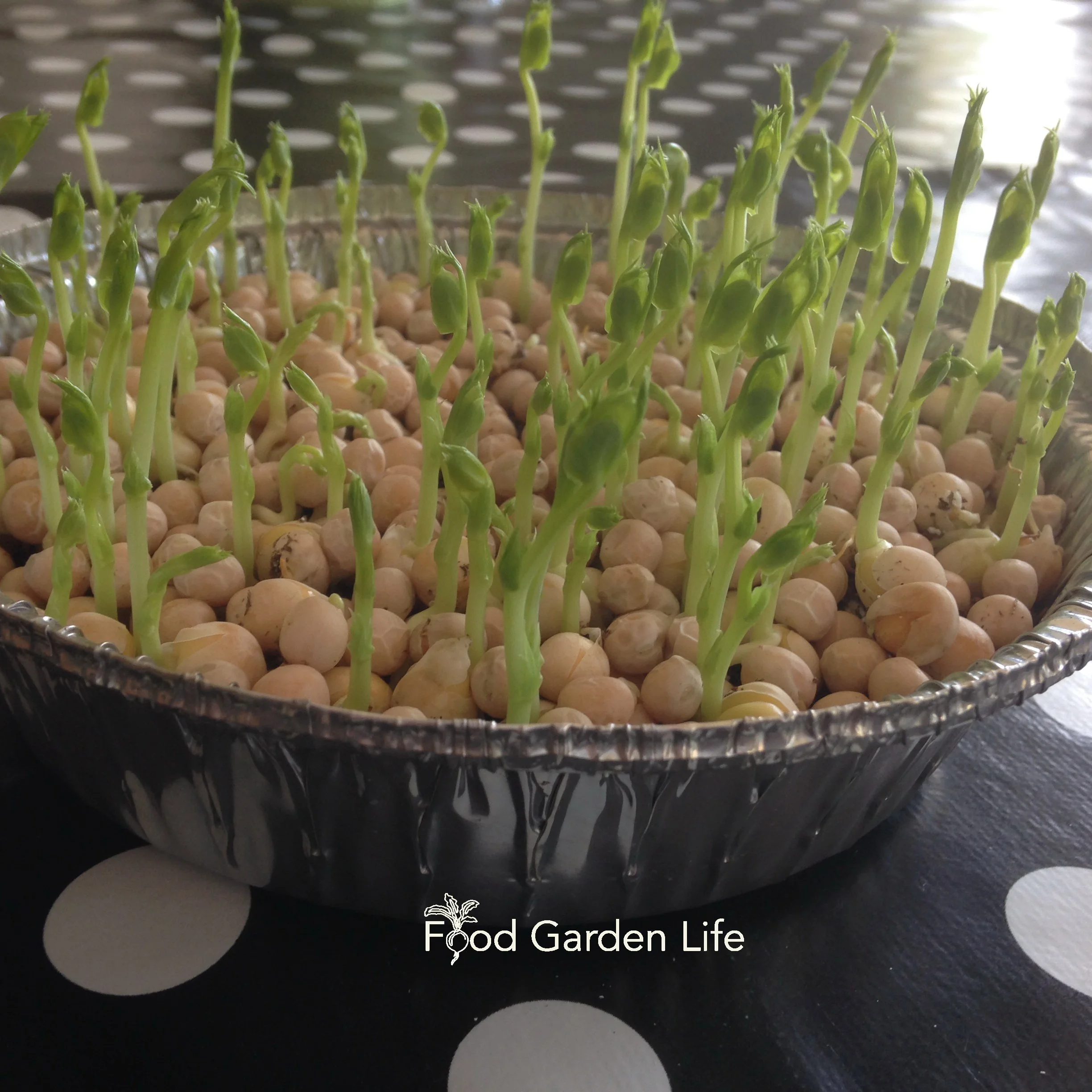

Growing Microgreens at Home is Easy

Pea shoots grown at home: All you need is a handful of dried peas, a pie plate, potting soil, and a windowsill.

On a recent trip to the grocery store I noticed small containers of pea microgreens. Gulp…a whopping $4.99.

The same amount of pea microgreens grown at home takes only a handful of dried peas, a pie plate, potting soil, and a windowsill.

Growing microgreens costs pennies—and it’s easy.

The setup is very simple. The materials are easy to get. There’s no need for fancy lights or equipment. And you can grow microgreens indoors any time of year.

Keep reading and I’ll tell you how to grow your own microgreens.

What are Microgreens?

Microgreens are immature plants. They’re often vegetable or herb plants. There are a few other fun ones, like sunflower and corn (deliciously sweet!)

They’re harvested while the plants are small and the stems still tender. Harvesting means cutting off the tops. Seems brutal, but it’s a short-term crop.

Why Grow Microgreens?

They’re easy to grow, quick to mature, and inexpensive: A perfect indoor crop for home gardeners.

I have a big garden, with lots to harvest into the fall and early winter. But microgreens are my go-to green crop for winter. When I want a green salad mid-winter, instead of lettuce or other leafy greens, I chop up microgreens.

If you’re already a microgreen connoisseur, another reason to grow microgreens at home is that you can grow microgreen crops you won’t find at the grocery store.

Grow microgreens with different tastes:

Spicy (e.g. radish)

Sweet (e.g. pea)

Bitter (e.g. lentil)

Nutty (e.g. sunflower)

A colourful tray of fresh microgreens.

And microgreens with different colours:

Light green

Dark green

Red

Purple

Crops for Home Microgreens

There are many different plants suited to a crop of microgreens, including vegetables, herbs, flowers—and others, like some common field crops!

Before you grow something into a microgreen, make sure it it’s edible. I’ve listed many microgreen crops below. If in doubt, see what seed vendors sell for microgreens.

Vegetable Seeds for Microgreens

Here are vegetables that are commonly grown as microgreens:

Grow microgreens from many different types of seed, giving you different tastes, textures, and colours.

amaranth, arugula, beet, broccoli, cabbage, carrot, chard, cress, dandelion, kale, kohlrabi, mizuna, mustard, onion, orach, pac choi, pea, radish, tatsoi, watercress

Herb Seeds for Microgreens

Here are herbs that are commonly grown as microgreens:

basil, cilantro, dill, fennel, lemon balm, parsley, shiso, sorrel

Flower Seeds for Microgreens

Here are flowers that are grown as microgreens:

borage, celosia, marigold, sunflower

Field Crop Seeds for Microgreens

Here are field crops that can be grown as microgreens:

alfalfa, barley, clover, chickpea, corn, lentil, quinoa, wheat

Microgreen Seed Mixes

There are also seed mixes with more than one type of microgreen seed, giving a blend of taste and colour.

My favourite is pea microgreens—a.k.a. pea shoots. They’re sweet, crunchy, and easy to grow. I also love sunflower microgreens for the delicious nutty flavour. (The husk of the sunflower seed is easy to remove as the sunflower microgreens get bigger.)

Buying Microgreen Seeds

Dried green peas from the grocery store.

When shopping for microgreen seeds you might come across the interchangeable terms “sprouting seeds” and “microgreens seeds.” It means the seeds are untreated and uncoated. They’re usually sold in a larger volume than seeds intended for the garden—so it’s better value. And in some cases, it means that the seed company tests the seed to be sure there’s no contamination with pathogens.

I use dried peas and lentils from the grocery store—the same dried whole peas used for cooking.

Stick with food grade seeds from the grocery store or seeds sold for microgreens.

Seed sold for planting in the garden is sometimes “treated,” which usually means with fungicides. Treated seed is not suitable for growing into microgreens.

First Microgreen Crop? Give Peas a Chance

First time growing microgreens? I like the peas-and-pie-plate approach. It’s easy!

I recommend pea microgreens (also known as pea shoots) as a first microgreen crop. Dried peas are easy to find at the grocery store, easy to grow, and have a sweet flavour—much like snow peas and snap peas.

It doesn’t matter whether you use green peas or yellow peas—the key thing is to use whole peas, not split peas…they won’t grow!

How to Grow Microgreens at Home

Choose a Location to Grow Microgreens

When you grow microgreens you’re using the energy saved up in the seed. The goal is a tender young stem and leaves that you cut off and eat as a green. That means you don’t need bright light. It doesn’t matter if the plants are gangly.

Supplies for Growing Microgreens Indoors

Here are supplies to grow microgreens at home:

Seed

Potting soil

Container

Spray botte (optional)

Soil for Microgreens

The potting soil is to hold moisture and let the microgreen plants anchor themselves as they grow. You don’t need to supply nutrients because the plants are using energy stored in the seeds. Start with fresh soil every time—don’t reuse soil.

Moisten the potting soil before planting.

Use a soilless potting soil. Coir or peat moss as a growing medium work well too.

Containers for Microgreens

There are lots of options for microgreens containers. You only need to have about an inch of potting soil, so any shallow container works.

Here are examples:

Lentil microgreens growing in a plastic container.

A standard 10”x20” plant tray

A pie plate

Takeout containers

Smaller containers dry out faster, so you’ll need to water more often.

If you trust your judgement with watering, don’t make drainage holes. But if you think you might overwater, punch a few holes in the bottom of your container.

Spray Bottles

A spray bottle for microgreens is optional. I don’t use one. Some gardeners use a spray bottle to avoid splashing around small seeds. Instead, you can water carefully with a gentle stream of water.

How to Plant Microgreens

Soak larger seeds such as pea, lentil, and sunflower overnight. (Soaking gives a faster, more uniform germination.)

Put an inch or two of potting soil in the container.

Put seeds on top of the soil, spacing them so that they’re close to each other, but not covering each other. Don’t cover seeds with soil.

Water so that the soil is moist but not wet. (You want the soil moist, not wet...don’t float your seeds!)

Place under lights or on a windowsill.

Pea Microgreens Step by Step

Top Tip: When seeds are in contact with the soil you get a faster, more uniform germination. Put something heavy over the microgreens after sowing. The weight pushes down on the seeds so that they are in contact with the soil. (I stack my pie plates full of seeds.)

Don’t do this: Don’t fertilize them. There’s enough stored energy in the seed to grow the microgreens until harvest.

Location for Microgreens

Growing microgreens under lights. Less light is OK too.

You don’t need perfect growing conditions, so make do with what you have. If you have a bright window or set of grow lights, these work well.

Low light is also OK too, because the plants are growing using energy stored in the seed. I’ve grown them on a dim countertop.

The warmer the temperature, the more quickly the microgreens grow.

Seeds sprout more quickly in warmer conditions. Here are ways to give your microgreen seeds more heat:

A heat mat

A sunny windowsill

The top of a hot-water radiator

A heated floor.

Growing Your Microgreen Crop

If you put something heavy on top of the seeds, remove it after a couple days. These amaranth microgreens were covered a bit too long…but they’ll bounce back.

Check daily to make sure the soil is moist and to see if your seeds are germinating.

If you put something heavy on top of the seeds, remove it after a couple days.

Harvesting Microgreens

Harvesting Pea Shoots

When I grow windowsill pea microgreens over the winter at room temperature, I expect to harvest them about 2 weeks after sowing.

Harvest microgreens when they get 3-4 inches tall, a size when they are tender and not fibrous.

The first cut is the largest. There might be a couple more smaller harvests with pea shoots. (Not all microgreens regrow from what remains after harvest.)

Spotty germination in this container of pea microgreens because the potting soil got too dry.

When the energy in the seeds is used up and they no longer send up new growth, compost them.

Harvesting Other Microgreens

The height and time to harvest depends on the microgreen crop. Most crops are harvested before a second set of leaves grows.

Harvesting Microgreens: Here's a Hack

In commercial operations growers often use shallow trays so that it’s easy to harvest microgreens with a knife. (With a deeper tray, the edge of the tray gets in the way of cutting close to soil level.)