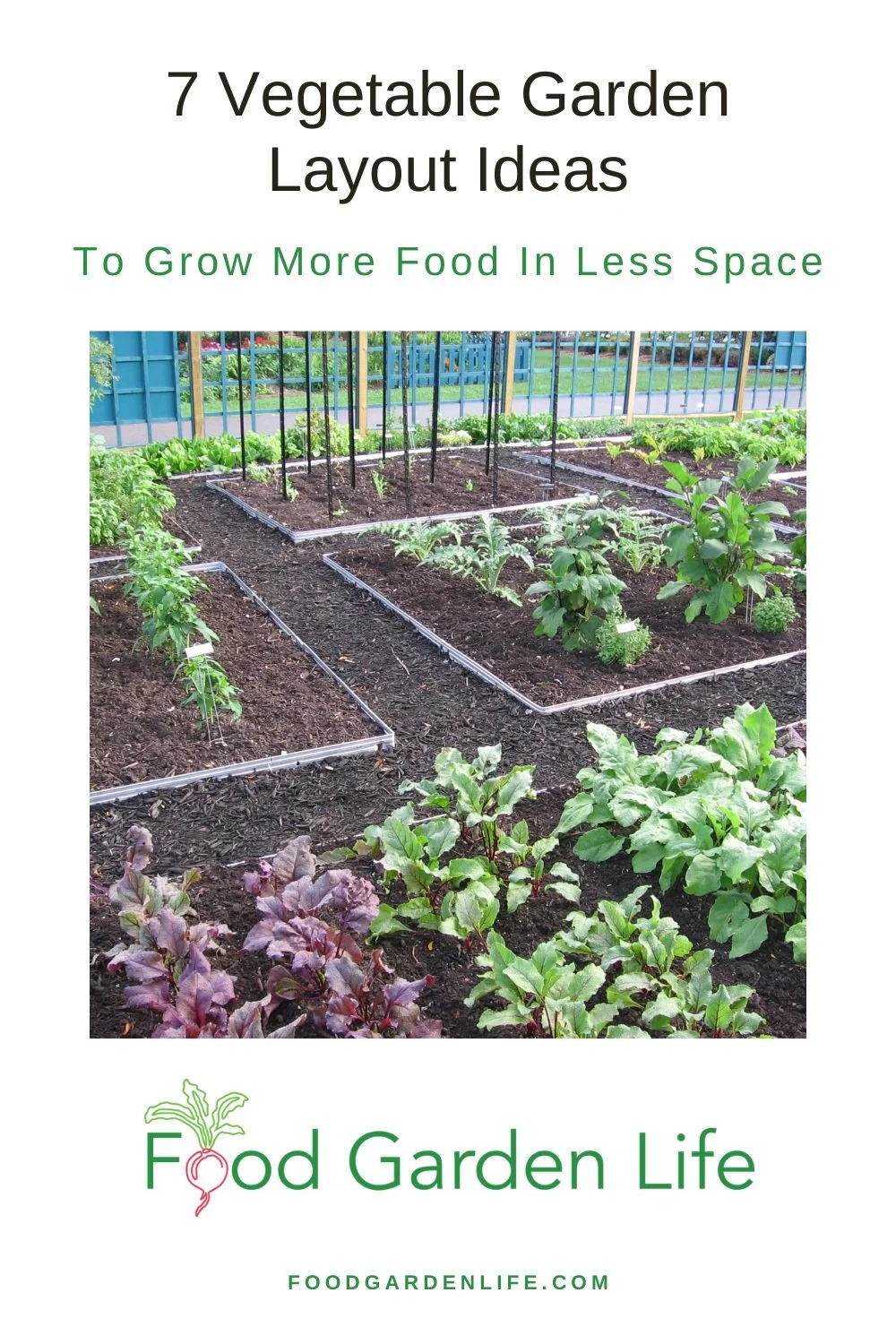

7 Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas To Grow More Food In Your Garden

By Steven Biggs

Garden Layout for Vegetables

Need help planning a vegetable garden layout? Here are ideas to get your started!

I was delighted when a neighbour removed her front lawn to grow vegetables.

One more edible garden in the neighbourhood! It's a nice departure from the driveway-and-shrub aesthetic around here.

She asked me to help her plan her vegetable garden layout.

But...

I didn’t have a simple explanation about how to make a vegetable garden layout! Keep reading, because this inspired me to map out the way I think when I'm veggie gardening.

As we studied her small, partially shaded front yard, I saw numbers in my mind—distances between plants, between rows, and between crops. I saw centimetres and inches (because we’re in Canada and can’t decide on which to use.)

There's a simpler approach, and I share it below.

Before we get to my top tips: Remember that there are lots of possible vegetable garden layouts. There are many ways to organize and space out vegetables in a garden. There's the growing. And then there's a creative aspect to it. That means that two gardeners given the same garden bed can come up with completely different layout plans. Enjoy the creative journey! There’s no perfect vegetable garden layout—there’s a layout that suits you and your situation.

Keep reading for 7 tips to help you come up with a vegetable garden layout that suits your situation:

1. Grow in Blocks

Rows are for Farms

There’s lots of bare soil when growing in rows. Grow in blocks instead of rows to optimize the use of space.

In a traditional row-gardening layout, there's space between rows for cultivating. That cultivating chops down little weed seeds that are germinating. Gardening this way allows one person to weed and tend a lot of plants when labour—not space—is limited.

Planting in rows can make sense on big pieces of land.

But in a home vegetable garden, we're growing on a different scale. In a home veggie garden, we’re limited by space.

And that means growing some vegetables in blocks, instead of spread-out rows of plants. By growing in solid blocks of plants, we fit lots of plants into a plot and have less bare ground showing.

(There are still some vegetables that will do best as single rows of plants, and we'll cover them below.)

Perennial Plants

If your garden design includes perennial vegetable plants, give them a separate block.

2. Grow Vegetables Vertically

Add height to your garden plan! A bamboo-and-wire-mesh A-frame is one way to make good use of the vertical space in a garden.

Plan for the dimension of height in your garden. Use the vertical space! This just means growing some plants upwards instead of letting them sprawl around the ground.

For example:

Growing a climbing plant up a stake or trellis frees up space on the ground for different plants.

Grow crops in layers. By growing vertically, you can also grow more than one crop in a small space. For example, make an A-frame for cucumbers, and underneath the A-frame, plant leafy greens that benefit from some shade during the summer.

And one more idea if you're making layers in your garden: Hanging baskets. They're great for herbs and many of the leafy greens.

Climbing Plants for Vertical Gardens

Here are a few of my favourite climbers to grow in a small space.

Malabar spinach (a vining spinach substitute, not really a spinach…but excellent during the heat of summer)

Achocha (a.k.a. Bolivian cucumber, it’s absolutely prolific, and a fun novelty)

Vining peas

Pole beans

Runner beans

Cucumber

Squash

3. Plant Densely, and then Thin

Seed Spacing…How Many plants?

Plant densely to grow more food in a small space. Here are densely planted carrots, and as the larger ones develop roots big enough to eat, they’re pulled out so there’s space for the remaining ones to develop.

Seed-spacing recommendations on seed packets and in articles are often geared towards commercial production. And these recommendations work fine in a home garden.

But…

Most plants do well with less than the spacing recommended on a seed packet.

So if you want to grow more food, plant more densely.

Forget Finicky

Commercial growers (or hard-core gardeners with big gardens) often use seeding machines to place seeds at a specific spacing. There are also hand-operated seed dispensers to help get perfect spacing.

Your plants won’t know the difference—and you can make your seeding less complicated by not being finicky.

Scatter-Seeding a Block is Not Finicky

When seeding a block, I hand-scatter seed. With practice, you can scatter seeds so that they are spread at approximately the distance you want. Don't sweat the exact spacing.

It’s not an exact process. You will get some seeds too close together; and some too far apart. (Remember, gardening is detox for perfectionists.)

Where seeds are too close, thin as plants start to grow.

Beets too close? Thin out a few and enjoy baby beet greens.

Carrots too close? Thin your block of carrots and have some baby carrots for supper.

When scatter-seeding blocks, you will use more seed than if you seed in rows.

That’s fine: It saves time and you get more veg from the same area.

4. Choose Crops to Maximize Your Harvest

To grow more food in less space, be strategic with your crop choices as you’re laying out a vegetable garden.

My first rule of vegetable gardening is to grow things you like. Sure, radishes are easy to grow. But do you like eating them three times a day?!

Here are three other things to think about as you fit more food plants into your space.

You might choose spreading crops that take a lot of space. That’s fine, just grow them upwards. You don’t see it in this picture, but there’s a whole crop of Swiss card below.

Next, avoid the space hogs. These are crops that take up a piece of garden for the entire growing season...and only give you something at the end of the year. That's right: if you have a small garden, think twice about those parsnips and Brussels sprouts!

Keep the vining space hogs, but grow them vertically (see above.) So instead of squash sprawling around the garden, grow it up a fence or trellis. (I’ve even grown squash along a cedar hedge!)

If you have a small plot, skip the stingy crops. I'm talking about something like edamame, which is easy to grow and delicious...but takes a fair bit of space considering what you get from it. You'll get way more bang for your buck with something like bush beans.

And let’s get back to the idea of rows versus blocks as we think about choosing which vegetables to grow.

What to Grow in Blocks

Here are examples of crops that I like to grow in solid blocks, instead of rows.

Beet

Carrot

Leafy greens

Garlic

What to Grow in Rows

It makes sense to grow certain crops in rows. Here are the ones I prefer to grow i rows:

Potatoes (so I can easily "hill" them)

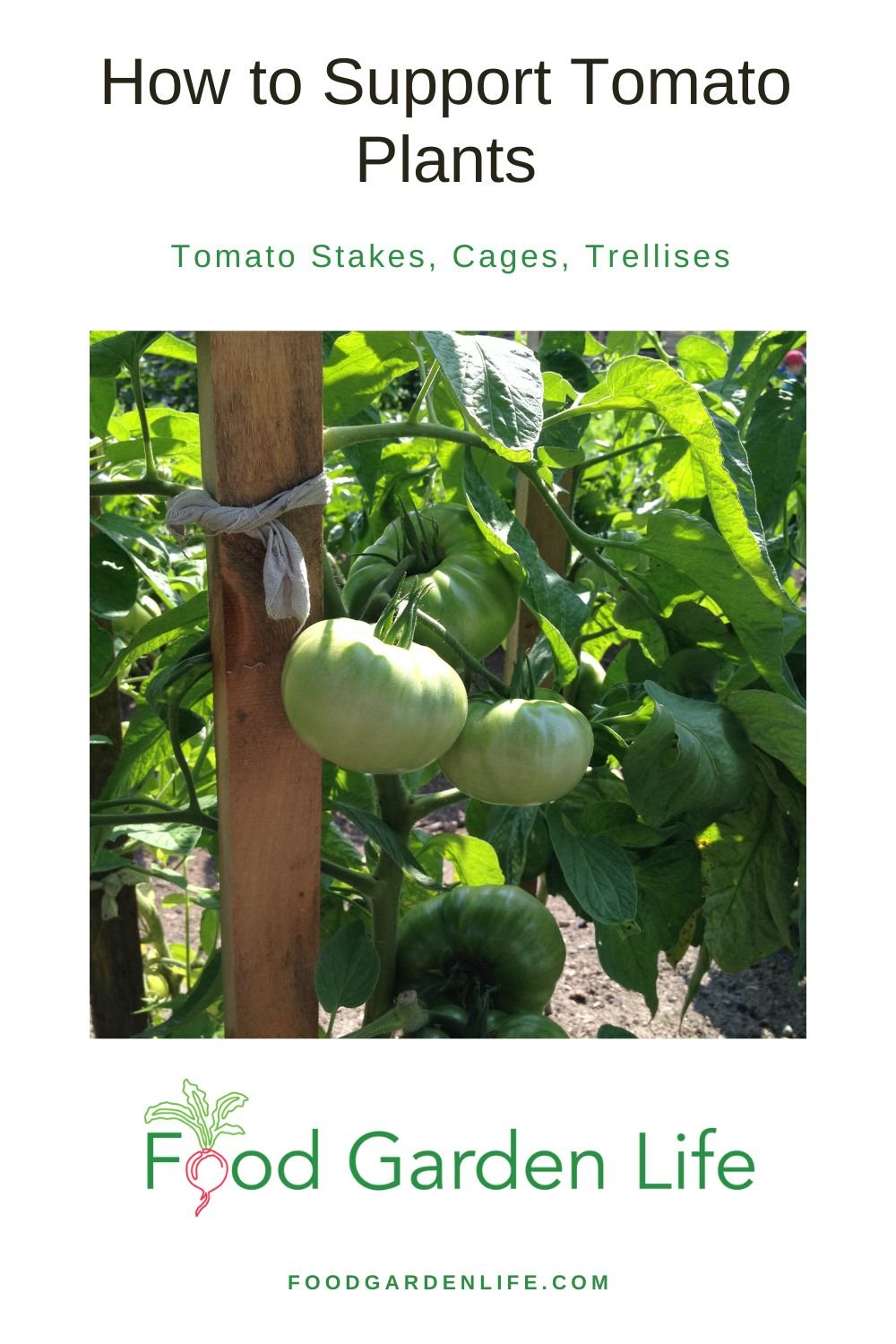

Tomatoes (because I stake them, and it's easiest when I can access them from both sides)

Peas (for ease of picking)

Pole beans (for ease of picking)

5. Keep Pathways to a Minimum

How much growing space could you add in this layout if the pathway down the middle didn’t go all the way through the bed? Lots!

An easy way to grow more food in less space has nothing to do with the distance between your plants!

Use less of the available ground for pathways.

As you map out your beds and pathways, play around with different layout options. Easy access is important, but sometimes there are ways to plan a garden that has access, but fewer pathways. A simple way to do this is with dead-end pathways that go part of the way into big beds…but not all of the way through. That way less of the growing space is sacrificed for pathway. (Having trouble picturing this? Imagine a keyhole garden, where there’s a pathway into the middle—but it doesn’t go all the way through.)

6. Plant Two Crops Together

Radishes and carrots seeded at the same time,. The radishes are ready to harvest, while the carrots roots are nowhere near ready for harvest, even as baby carrots.

Companion planting is another way to fit more plants into your vegetable garden.

Plant two vegetables in the same space—ones that are good companions because they mature at different speeds.

My favourite combination is fast-growing radish, with slower-growing carrots or beets.

When I scatter carrot seed on a block of garden, I also scatter radish seed. The radish grows much more quickly than the carrot, and is ready to harvest while the carrot seedlings are still quite small.

Harvesting the radishes frees up space for the carrot seedlings, and as the tap root of the radish comes out, it also loosens the soil around the carrot seedlings. It's a perfect combination.

(There is a lot of rubbish information out there on companion planting. I suggest this science-based book: Plant Partners: Science-Based Companion Planting Strategies for the Vegetable Garden.)

7. Grow Succession Crops

Rapini is one of my favourite summertime succession crops.

Growing vegetables in succession as each parcel of your garden makes sure none of it goes unused during the growing season.

As your spring-planted cool-season crops finish, plant a heat-loving crop for summer.

Bush beans done? Sow some beets.

Garlic done? I like to grow rapini (and for those of you who are avowed rapini haters because of the bitterness, get yourself a bowl of orecchiette pasta with rapini and some chunks of spicy sausage fried to crispy, and you’ll see rapini in a different light.)

Need more Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas?

In Edible Garden Makeover I walk you through lots of vegetable garden layout ideas, raised beds, making garden beds, raised beds, and lots of other ideas that help you grow your own food in a way that suits your setup. I help you imagine an amazing kitchen garden, and also an entire edible garden layout. Find out how you can make your yard into an edible landscape.

Still Not Enough Space?

Pin this post!

If you're using these seven approaches to make the best vegetable garden layout for your garden area, and you still want to grow more, think about adding containers to your vegetable garden.

Plant vegetables in containers on:

Paved spaces such as driveways

Decks or balconies

You can also incorporate containers as part of a vertical garden, to add the element of height. (I've squeezed in pepper crops between an asparagus and horseradish patch...where normally they wouldn't have stood a chance because of the competition. But because they were elevated above the ground in a container, they got sun exposure and had lots of growing space in the container.)

One more space-making idea for you, something that I've used to transform a long, little-used driveway into a tomato oasis.

This idea is quick to set up, easy to care for, and inexpensive compared with permanent container or raised-bed systems.

Add a straw-bale garden to your garden layout. Find out more about straw-bale gardens.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More Gardening Ideas

Courses

Here are self-paced online courses to help you grow an awesome vegetable garden.

These Edible Perennials and Perennial Vegetables Make a Delicious Edible Landscape

Edible perennials are perfect for an edible landscape! Find out which ornamental perennials are edible, and get ideas for perennial herbs and vegetables.

By Steven Biggs

Grow a Grazing Garden with Edible Perennials and Perennial Vegetables

When I was a child my dad showed me how to take a leaf of stonecrop sedum, methodically press the whole surface of the leaf between my thumb and forefinger to soften it, and then gently push sideways to loosen the skin on the front and back.

Once the skin was loose, we’d blow into the sedum leaf to inflate it – like a little balloon!

It’s a fun trick for a kids. And I still have fun showing it to kids who visit my garden.

Multi-Purpose Plants

In a small-space garden, I like to include multipurpose plants, plants that are more than just ornamental. Edible perennials and perennial vegetables are great for small-space gardens.

Stonecrop Sedum flowers late in the summer. And it’s edible!

Stonecrop sedum is very ornamental. It’s a reliable, easy-to-grow perennial that flowers in the late summer when most other perennials are done flowering.

It also adds winter interest to the garden. I leave the dry stalks and flower heads in the garden all winter. They add texture and catch the snow.

Beyond it’s ornamental appeal, chalk up two other things for stonecrop sedum (or, as Dad always calls it, frog’s belly.)

The balloon-like leaves are amusing for kids (and adults too!)

It’s edible. You can eat the leaves. They’re mild, slightly lemony.

Keep reading for some of my favourite edible perennials, including herbs, ornamental perennials, and vegetables.

Use Edible Perennials in the Landscape

Traditional vegetable gardening involves a lot of annual crops and annual preparation of the ground. It includes starting transplants indoors, sowing seeds directly into the garden, and preparing the garden soil to make a nice bed.

Even no-dig vegetable gardening systems usually include some sort of soil preparation, whether it’s solarizing the ground (by covering with tarps), scuffing the soil surface to kill small weed seedlings, or mulching.

With this traditional approach to food gardening, there’s often a focus on growing enough to preserve by canning, freezing, or drying.

Perennials for an Edible Landscape

What if you just want to be able to go out into your garden and pick something for the meal you’re about to cook? To see what looks good in the garden – and see what inspires you to be creative in the kitchen?

An attractive edible perennial: Airy yellow flowers and a bronze coloured leaf make bronze fennel a beautiful addition to a perennial garden. And leaves and flowers are edible too!

I call this “grazing.” It’s picking just enough for the meal at hand, and letting what you find in the garden inspire what you create in the kitchen.

If you’re a fan of the potager-style garden, which mixes up veggies with herbs, edible flowers, flowers for cutting, and fruit, you’ll get the idea. We’re talking about a grazing garden.

So let’s take this idea of a grazing garden and use it in our perennial flower beds, dotted the landscape with perennial plants that are edible and look nice. This approach to gardening is a great way to grow some of your own ingredients even if you don’t have the space or the time to undertake a more traditional vegetable garden.

Here are some of my favourite edible perennials for a grazing garden:

Perennial Vegetables and Herbs

Lovage deserves a space in any ornamental perennial bed. The celery-like leaves are great in soups and salads.

Asparagus: After you’ve finished harvesting asparagus spears in the spring, this perennial grows into a tall, ferny plant that adds great texture and movement to a garden. Because it’s tall, put it at the back of the garden. Support it to prevent it flopping onto its neighbours.

Bronze Fennel: The feathery, bronze leaves are edible, as are the flowers. The pollen can be used to decorate a plate: Tap the flowers over a white plate to adorn it with the brightly coloured yellow pollen. I like to use the seeds when I make sausage.

Chives: Both leaves and flowers are edible. A tidy, well-behaved plant that looks great when used to edge a garden.

Horseradish: The root is grated to make the well-known condiment. Leaf pieces are sometimes added to pickles. This is a bomb-proof plant with a deep root system that’s hard to remove once established, so put some thought into where you would like it to be in the long term.

Jerusalem Artichoke: This one is in the Weed Guide of Ontario…so beware. But it’s a versatile plant, taking full sun to part shade. The tubers are plentiful.

Lemon Balm: Use young leaves in salads, and dry leaves for tea. This is not a timid plant; it spreads. But I love if for the fragrant foliage. Plant it somewhere where you’ll brush against it while in the garden and you’ll be glad you have it.

Lovage: My neighbour Dave says that this is the secret ingredient for an award-winning tomato soup. The leaves have a celery taste. It’s an imposing perennial that deserves a space in any ornamental perennial bed.

Mint: My daughter got 19 types of mint one year: chocolate mint, spearmint, pineapple mint… There are so many types. It’s excellent for teas, and we enjoy making mint ice cream. Mint can be invasive. So grow it in containers if you don’t want it to overrun your garden. But if you have a shady corner where not much grows, this might be a suitable place to plant your mint in the ground.

Oregano: A well-known herb that is hardy and an excellent ground cover too. When it’s in bloom watch to see what a bee magnet it is.

Rhubarb: My neighbour Chris planted it next to his pond because the big leaves are so beautiful. Easy to grow and productive. Recommended for sun, tolerates part sun very well. Find out how to force rhubarb indoors in the winter.

Sage: Along with the common grey-green leafed sage, there are varietgated and tri-colour varieties. If, like me, you’ve over-saged the thanksgiving turkey stuffing one too many times and don’t care if you ever cook with it again, some of these tricolour sages still make a beautiful addition to a herb garden.

Sorrel: My favourite. Easy to grow, rarely for sale at the supermarket. I use these tangy leaves mixed in with salad greens, to make soups, and when braising fish and poultry. Think of sorrel as a lemon substitute for northern gardeners. There’s wild sorrel, as well as large-leaved cultivated varieties.

Edible Ornamental Perennials

Daylily flowers and buds are edible.

Bergamot: Great for attracting pollinators, very ornamental – and edible. The leaves can be used to make tea. And the edible flowers are nice when tossed into a fruit salad.

Daylily: A perennial that has naturalized in some rural areas here in southern Ontario, it’s grown as a vegetable in other parts of the world. Unopened flower buds are a great addition to a stir-fry. And the flowers are an excellent garnish. Idea: How about a daylily flower instead of an ice cream cone?

Hosta: This ornamental perennial is a very widely used perennial. It does well in shade, makes a good ground cover – and the unfurled leaves in spring are nice steamed and buttered.

Stonecrop: Like hosta, a perennial garden workhorse, with flowers late in the summer when many other plants in the perennial garden are done blooming. But the leaves are edible and can be used in salads. And…there’s the fun of blowing up the leaves!

More Edible-Landscape Ideas

Plant ideas, techniques, and creative ideas to transform yards into fantastic edible landscapes.

Ripen Green Tomatoes to Extend Your Harvest

Find out how to ripen the green tomatoes that you still have in your garden, by picking them before the first frost, and bringing them indoors.

By Steven Biggs

How to Ripen Green Tomatoes Indoors

You can eat homegrown tomatoes through the winter. No greenhouse needed.

I’ve even eaten my own homegrown, “fresh” tomatoes in April. These are tomatoes I picked green the previous October, just before the first fall frost killed the plants. Then, I ripened them indoors.

You don’t need special conditions to ripen your green tomatoes because unripe tomatoes that have reached a “mature” size (nearly the final size) will keep ripening after they’re removed from the plant.

You can prolong your tomato harvest for weeks – even months.

Keep reading for pointers on picking, storing, and using your green tomatoes in the fall.

How do they Taste?

A plate of tomatoes picked green and ripened indoors.

A vine-ripened tomato from the garden has better flavour. That’s because tomatoes ripened on the vine in the garden develop more sugars and acids.

But a green tomato ripened indoors can have a respectable flavour – and it’s certainly far better than the insipid, mealy excuses for tomatoes found at grocers over the winter.

When to Pick Green Tomatoes for Indoor Ripening

Pick your green tomatoes before the first frost in the fall. Tomatoes exposed to frost get mushy and don’t store or ripen well indoors.

I pick tomatoes that are a mature size, as well as small, undeveloped tomatoes.

What to Pick

I pick everything:

I leave tomatoes that are already colouring up on the kitchen windowsill.

Tomatoes that are a mature size to ripen indoors.

Tomatoes that are small and not fully developed to cook or use in preserves (see my green tomato mincemeat recipe below).

How to Harvest Green Tomatoes

I pick larger tomatoes individually, leaving a small bit of stem attached. The reason that I like to leave a bit of stem attached is that with some tomato varieties, it’s easy to tear the skin while trying to remove the stem.

I leave cherry- and grape-type tomatoes on the stem and harvest the whole cluster.

Another approach is to harvest the whole plant. Cut off entire branches – or even cut off the stem at ground level, leaving the unripe green tomatoes on the plant.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

You Control the Ripening Speed

Small tomatoes that are not close to the final size won’t ripen well, but can be used in the kitchen.

Mature tomatoes give off ethylene gas, which causes them to ripen to ripen more quickly. All we have to do is tweak how much of this gas stays around the tomato.

You can stagger the ripening of your green tomatoes using two things:

Temperature. At warmer temperatures ripening happens more quickly.

Ethylene gas. This is the gas the mature tomatoes give off – and which stimulates ripening. If you want to speed up ripening, let the gas accumulate around the tomatoes. If you want to slow down ripening, allow air movement so the ethylene disperses.

How to Ripen Green Tomatoes

I lay out my green tomatoes in plastic trays lined with newspaper.

You don’t need sunlight to ripen green tomatoes.

There are a number of ways to ripen green tomatoes indoors. I lay out my green tomatoes in plastic trays lined with newspaper. (The newspaper prevents smaller tomatoes from falling through the holes; and absorbs juice from any tomatoes that rot.)

I keep the tray in a cool room in my basement. As tomatoes start to show colour, I bring them up to the kitchen to put on my windowsill, where it’s warmer – and where I monitor them more closely as they finish ripening.

If you want to speed up ripening, just capture some of the ethylene gas by putting the tomatoes in an enclosed space. Here are ways to capture some of that ethylene:

Speed up ripening by putting the tomatoes in an enclosed space. Adding a ripe apple or banana speeds it up more.

Place them in a closed drawer.

Place tomatoes in a closed paper bag (preferable to plastic, which doesn’t breathe at all).

Lay them out in a tray like I do—or on a shelf—and cover with a sheet of newspaper.

Wrap individual tomatoes in newspaper.

If you’ve left on pieces of stem, just be careful not to let the stem puncture any other tomato.

The Banana Trick

Bananas and ripe apples give off ethylene, so you can put a banana or apple in with tomatoes to provide more ethylene and speed up ripening. (I find I don’t need to do this, they ripen fast enough for me.)

Hanging Tomato Plants

If you’ve harvested entire stems or entire plants, simply hang the stems or plants in a cool, dark area and let the tomatoes slowly ripen.

I’m not a fan of this approach because as the tomatoes ripen, they detach from the stem and…splat!

As tomatoes start to show colour, I bring them up to the kitchen to put on my windowsill.

Varieties Suited to Indoor Ripening

A thick-skinned tomato variety that lasts me until spring.

You can ripen all types of tomatoes indoors, but thick-skinned varieties are best for longer-term indoor ripening.

Thin-skinned beefsteak varieties are more prone to rot. It doesn’t mean you can’t ripen these ones indoors – it just means they’re less likely to last long into the winter.

Green Tomato Ripening FAQ

What else can I do with green tomatoes?

I love green tomato fried in the skillet in bacon fat, sprinkled with salt and garlic powder. Some years I make a green tomato mincemeat. You can also make lactic-acid fermented green-tomato pickles – same idea as sauerkraut and brined dill pickles, except using green tomatoes.

Should I wash green tomatoes after picking them?

I don’t. Some people wash them in a bleach solution to disinfect them. Sounds like a lot of bother to me…and I like to keep gardening simple. I wash them once they are ripe, just before I use them.

Can I ripen green tomatoes indoors in the summer too?

Yes! I’ve had large 2-3 pound tomatoes, and just as they ripen a squirrel came along and ate off a corner. It would have been better to pick these before they were fully ripe, and ripen them indoors.

Can you really get them to last until April?

Green tomatoes with cracks and blemishes often rot, so sort them out of your tomato harvest and cook them instead of trying to ripen them.

Yep! The trick is to grow a “keeper” tomato variety. I grow one that came to me from my Dad’s friend Dino. It’s small and thick-skinned...not the juiciest tomato, not the most flavourful tomato – but I can make bruschetta with my own fresh tomatoes in early spring. Not bad!

What about tomatoes that have cracks or blemishes on them?

Tomatoes with cracks and blemishes will not keep for a long time. If they are close to colouring up, you can try to ripen them – just watch closely so you’ll see if they begin to rot around the damaged area. Otherwise, use these tomatoes in one of your green-tomato recipes.

Want to Store More of Your Own Food?

Storage Crop Ideas for Your Vegetable Garden

Here are 25 storage crops you can grow in your garden.

More Tomato Articles

Tomato Interviews

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles: Growing Vegetables

Courses: Grow Vegetables

Top Vegetables to Plant in August for a Continuous Harvest

Top crops to sow in August for a late-summer and fall harvest.

By Steven Biggs

As August rolls around the mid-summer vegetable garden harvest includes heat-loving crops such as tomatoes, okra, and eggplant.

(August is also when many people realize they've planted too much zucchini!)

And by early August there's usually space open for succession crops as early crops finish:

The garlic and onions are done

Pea vines have withered in the summer heat

Early beans are kaput

There's still lots of the growing time left before the snow flies. Early August is a good time to sow seeds for fall vegetable gardening.

Not sure what to plant in August? Keep reading for ideas about what to plant in August.

Vegetable Garden Crops to Sow in August

August is the time to sow cool-weather crops for the fall garden.

It’s also last call for some fast-growing heat-loving crops too, such as bush beans.

By August, the remaining frost-free window is getting shorter. So our focus is crops that mature fairly quickly.

Tips for Planting in August

Summer conditions such as dry soil and scorching heat can be hard on seeds sown outdoors.

Here are tips for direct-sown crops:

Water regularly for faster, more consistent seed germination in hot weather

Where possible, shade young plants of heat-sensitive crops such as lettuce with row cover or mini hoop tunnels

Grow varieties that are fast to mature

Find out your first frost date so you can pick suitable crops (Here in Toronto I know that I can expect my first frost in late October.)

Top Late-Summer Crops for August Planting

Wondering what to plant in August?

If you are looking for ideas of what to plant in August, here are some of my favourites.

Beets

Beets are an excellent crop to plant in August.

My grandmother always made us pickled beets from perfect little cherry-sized beets. If you want smaller beets for a fall harvest, keep planting beets into August.

(Experiment with varieties and planting dates to figure out what works well in your area. The worst case scenario if you plant too late is that you will have lots of beet greens for your fall salads.)

Summer-Sowing Tip: Throw some radish seeds over top of your newly planted beet seeds. The radishes mature more quickly than the beets.

Find out more about storage crops such as beets.

Bush Beans

Keep harvesting beans all summer by sowing more bush beans in early August.

This is the last call to sow bush beans!

Summer-Sowing Tip: Speed up bean germination by soaking seeds in water overnight before planting.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Cabbage Family

August is a good time to transplant broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage seedlings

Now is a good time to transplant broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage seedlings into the garden. There’s not enough time to seed these directly in the garden at this time.

If you haven't already started your own seedlings, there’s no shame in buying them!

Don't worry if you don't have broccoli, cauliflower, or cabbage seedlings. There are other cabbage-family crops that don't need as much time to mature.

Kale. Planting kale seeds outdoors in August works well.

Rapini. A favourite of mine in the summer garden.

Carrots

Carrots are a must-have crop for serious succession gardeners.

Summer-Sowing Tip: Carrot seeds are fairly small, and can have a hard time breaking through dry, crusty soil in the summer. So water daily. Or, cover the bed to keep it moist. (I use old boards; and some people use burlap.)

Carrots and beets are root vegetables that store well in the ground for an early winter harvest. Find out about storage crops.

Keep sowing carrots in August.

Leafy Greens

Start planting lettuce for fall harvest in August. Grow lettuce in partial shade, or protect plants from full sun with row cover or a hoop house.

Many of the cooler weather leafy greens such as lettuce and spinach have faded by mid-summer. But August is the time to start planting more for a late summer and fall harvest.

I plant these cooler weather leafy greens about 8 weeks before the first fall frost.

Swiss chard usually keeps going in my garden all summer long. But in August I plant more, so that I have lots of small chard leaves to enjoy in the fall.

Green Onions

Get extra onion sets in the spring for planting in August.

When I buy onion sets in the spring I get extra sets to store in the fridge until August, when I start planting more so that I can enjoy green onions into the fall.

Turnip and Rutabaga

Often overlooked, and easy to grow.

And don’t forget that with turnips you have both an edible root and greens. Find out about other plants with more than one edible part.

Still not sure about turnip and rutabaga? Mom’s rutabaga casserole includes apple, and is topped with buttered bread crumbs…a nice way to enjoy these crops.

More Ideas for Fall Crops

More Vegetable Gardening Resources

Articles + Interviews

Courses

5 Heat-Tolerant Salad Greens to Grow All Summer Long (Plus a Great Garnish)

Lettuce bolting in hot weather? Here are 5 easy-to-grow and heat-tolerant salad greens to grow in hot weather. (Plus a delicious heat-loving garnish for your salad!)

By Steven Biggs

Pick Crops to Expand Your Hot-Weather Menu

As hot summer weather arrives, many spring greens start to bolt. When they bolt (when they send up flower stalks) they stop producing tender leaves. It’s game over.

Find out how to slow down lettuce bolting.

One way to harvest a steady supply of green leaves over the summer months is with succession crops. Make ongoing plantings of bolt-prone crops such as lettuce, spinach, and arugula. (Look for heat-tolerant lettuces.)

Here's more about succession crops.

But there's another way to get a steady supply of summer salads: Grow heat-tolerant greens.

If you want hot-weather greens, keep reading. As warm weather arrives, add some of these other leafy greens to the garden to spruce up your salads.

5 Leafy Greens for Summer Heat

Here are five of my favourite heat-tolerant greens for the summer garden.

Amaranth Leaves

Amaranth is easy to grow and thrives in the heat. It loves hot summers!

Amaranth is a versatile plant and a great choice for spots where you want to weave together the edible and ornamental. It's grown for its edible seeds, its ornamental uses, and for its edible leaves.

The leaves can be eaten raw when young. They taste a bit like spinach. Use larger leaves cooked, in soups and stews.

This is a crop that confidently self-seeds. Grow it once, and you're set for upcoming years. As little amaranth seedlings pop up in my veggie patch, I curate—I pull out some of the small amaranth plants for the salad bowl, and leave a few to grow where I want larger amaranth plants.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Beet Leaves

Steal a few leaves from the beet patch to add to summer salads.

As I make salads with summer greens, I like to steal a few small leaves from the beet patch.

Beet greens are edible. Use young leaves raw in salad, and cook larger leaves. (I add mature leaves to borsch. Here's Mom's borsch recipe.) Eaten fresh, these young leaves have a slightly earthy taste, like their kin, Swiss chard.

Even though I grow this crop for its root, taking a few small leaves is no problem; just don't take them all from one plant.

There's one beet variety that I grow especially for its leaves: 'Bulls Blood' has vibrant red leaves that add nice colour to a bowl of summer greens.

Malabar Spinach

Malabar spinach thrives in hot conditions. As a vining plant, it’s also great if you want to add vertical elements to a vegetable garden.

Malabar spinach (Basella alba) thrives in the heat of summer. This vining plant usually takes off as the regular spinach starts to wane in the heat.

Malabar spinach, despite the name, is of no relation to spinach. It has fleshy, mucilaginous leaves that you can eat raw or add to a stir fry. You can also use it to thicken soups.

Best of all, this tropical plant keeps growing all summer long, through the heat.

I don't often see Malabar spinach plants at garden centres. If you want it, plan to grow it from seed. There is a green-leafed type, as well as a strikingly beautiful red-leafed type.

Malabar spinach is also a great crop for vertical gardening. Find out how to save space by adding vertical crops to your garden.

Sorrel

Garden sorrel is a perennial, and a useful salad green over the summer.

This is a favourite in our garden. Sorrel is a perennial leafy green crop that's up early in the spring. It keeps producing tender leaves all summer long.

Sorrel has a tangy taste. I think of it as a lemon substitute for northern gardeners. Add sorrel leaves to a mixed green salad—or when making a sauce add in sorrel, and as the leaves cook into the sauce they add a citrusy tang.

Here's a recipe for sorrel soup.

Garden sorrel (Rumex acetosa) is what you'll find at garden centres. I like ‘Profusion’ garden sorrel, a large-leaved variety that doesn’t bolt.

If you're a forager, you might find sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella). Both are edible, though I wouldn't plant sheep sorrel in a home garden...it's a spreader.

(There's also a weed called wood sorrel. It's part of the oxalis clan, with clover-like leaves. It's edible too...but I'm not proposing you grow it—it shows up on its own.)

Find out more about how to grow sorrel.

Swiss Chard

Swiss chard has a two-year life cycle, so during its first year, even during the heat of summer, it keeps on making leaves.

This is my favourite summer green. Swiss chard is a work horse; pick heavily and continually all summer and it keeps growing.

Unlike lettuce and spinach, it doesn't try to flower in its first year. That’s because it has a two-year life cycle...and that makes it a very valuable heat-tolerant green.

When picked young, the small leaves can go straight into the salad. I like larger leaves and the more substantial leaf rib in stir-frys.

Along with green varieties, there are many colourful ones that paint the veg patch a rainbow of colours.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

One More Hot-Weather Crop

Squash tips and tendrils are edible.

Here’s a crop that doesn’t fit into my list of hot-weather salad greens because we cook it. But I’m including it in this post because it’s a fantastic garnish for a summer salad, and it has great heat tolerance.

Squash Tips

Squash shoot tips, squash tendrils, and squash leaves are all edible.

But…cook them briefly. A quick sauté in olive oil does the trick. That’s because when they’re not cooked, they’re a wee bit prickly. But cooked, they’re transformed.

Squash has many edible parts on the same plant: There's the fruit, the flowers, tender stems, and then the leaves and tips. You can cook larger leaves too, but harvest them before they’re too fibrous.

More Vegetable Gardening Ideas

Articles

Want to browse our articles and interviews about vegetable gardening? Check out the Vegetable Gardening Home Page

Do you have a shady yard? Here are things you can grow: Crops for Shade

Trying to figure out how to fit as much as possible into your vegetable garden? Try these Vegetable Garden Layout Ideas

Interviews

Courses

Check out our self-paced online courses. The practical information is in bite-size chunks, so you can work through them at your own speed.

Succession Planting: Here's How You Can Harvest Vegetables Season Long

By Steven Biggs

Succession Crops are the Ticket to an Uninterrupted Harvest

"Succession planting" is when we grow more than one crop in the same space over the growing season. We grow a succession of crops.

As one crop finishes, the succession crop takes its place.

Many crops mature before growing season is done, leaving time to plant a second (or even a third) crop. This means we can follow our spring crops with warm season crops and fall crops.

A "succession crop" is just a fancy name for the crop(s) that come after the first crop is done.

Succession planting works in large gardens, small gardens—and even containers!

If you are interested in the idea of a continuous harvest, keep reading: This article explains how you can use the same garden space for more than one crop.

Plan for an Uninterrupted Harvest

As you plan your vegetable garden, there's more than one way to achieve successive harvests. See how you can slot these planting methods into your garden.

Find out more garden planning and layout ideas.

Different Crops - One Follows Another

A common succession planting method is follow one crop with another one. For example, when the summer harvest of green beans is finished, a new crop of kale for winter harvest takes its place.

Different Crops - At the Same Time

Planting carrots and radish together.

Planting two different crops at the same time is not really succession planting, but it's worth mentioning here because it's a useful idea in garden planning, and can be a good way to get multiple harvests from the same space.

Some people use the term companion planting to describe this idea.

Here are examples:

Fast-growing crops with slower crops: My favourite fast-slow combo is to plant beets in the same space as radish. The radishes grow much more quickly than the beets. So you'll have harvested the radishes by the time your beet seedlings need more space. (And don't forget...beet greens are edible too!)

Sun-lovers with Shade-lovers: Another example of putting two crops together is pairing a tall plant with a shade-loving plant. In this case, summertime lettuce (which lasts longer in shade) under tomatoes.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Same Crop - Staggered Plantings to Spread out the Harvest

By staggering plantings of a crop you can get a longer harvest window. This is especially helpful if you grow lettuce or other leafy greens that bolt quickly.

Unless you’re a market gardener, you probably don’t need an entire row of lettuce ready at once. So only plant part of the row. Then, a couple of weeks later, plant more of the same. And repeat.

Same Crop - Different Maturity Dates

Days to maturity (DTM) is a measure of how long it takes a crop to be ready to harvest. Get a few varieties of the same crop, each with a different DTM so that you have an ongoing harvest. Look for DTM on the seed packet or catalogue.

(The number of days it takes for a crop to be ready to harvest varies with growing conditions, so use DTM as a guide, not an exact planning tool.)

Find out more about seed shopping and lingo such as DTM.

Succession Crops

Succession crops are crops that don’t take the whole growing season to mature. They only need part of a season.

Here are common succession crops:

Bush beans are a common succession crop.

Leafy Greens (plan for successive sowings if you want leafy greens during the summer)

Beets (baby beets for pickling are often from a succession crop of beets planted in the summer)

Cabbage

Carrots

Bush beans

Green onions (I keep an extra bag of onion sets in the fridge, ready as a second crop when I need more green onions)

Kohlrabi

Radish and winter radish

Rapini (I like to plant rapini as a mid-summer succession crop when I harvest garlic in July, because it’s fast-growing and does well in the heat of the summer)

Rutabaga

Summer squash (a good second crop where you start off with early spring greens)

Swiss chard (does well in heat without bolting)

Winter squash

Turnip (I like turnip as a late-summer crop…and you can eat the leaves too!)

Find out how to slow down lettuce bolting.

Interested in growing storage crops? Here are 25 storage crops.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Sowing Summer Crops

Hot summer growing conditions are not always suitable for starting seeds directly in the garden.

That’s because:

In hot, dry weather, place a board over fine seeds to keep in soil moisture and improve germination.

Hot weather can affect germination.

In hot, dry summer conditions a crust can form on some types of soil.

Pest pressures are higher.

Here are tips to plant crop successions in hot weather:

Start transplant in pots, in protected conditions.

For plants that are best directly sown into the garden (e.g. carrots), place a board over the soil so that conditions are more moist for germination

Water regularly because dry conditions really mess up germination.

Transplanting Succession Crops

Summer conditions can make transplanting difficult because transplanting into the hot sun is a big stress for the plant.

So wait for a rainy or cloudy day if possible. At the least, don't transplant in the heat of the day.

Make shade for your transplants using mini hoop houses covered with shade cloth or a light floating row cover.

Or even easier: Put an inverted web tray over top of your transplant for a few days. (The webbed plastic trays from garden centres.)

And then water transplants regularly until they are established.

Lettuce transplants for succession cropping.

One Key to Successful Succession Planting

With intensive growing like succession planting, we’re taking more from the soil. That makes it especially important to manage soil fertility. Feed the soil by amending with compost between crops.

Final Succession Cropping Suggestions

Keep extra seed packets on hand for succession planting!

And don’t forget to grow microgreens indoors over the winter.

Find out how to grow our own microgreens indoors.

More Vegetable Gardening Articles

Courses

Prevent Lettuce from Bolting: 5 Ways to Beat the Bitterness

5 Ways to prevent lettuce from bolting as quickly.

By Steven Biggs

Delay Bitterness and Bolting Lettuce

Once day you're looking at a bed of perfect lettuce plants with juicy, tender leaves. Looks like you have enough lettuce for days.

But before you know it the lettuce heads change shape and start to stretch up in the centre. Your lettuce is bolting.

And with the change in shape comes a change in taste. Bitterness comes with bolting.

But there are ways that you can delay lettuce bolting. This article tells you how.

Bolting Lettuce Plants

It's a normal thing for a lettuce plant to bolt. Lettuce plants start out in leaf-making mode. They make leaves, get bigger, store energy.

But as the lettuce plant gets big enough—and as things around it act as triggers—the lettuce plant changes gears and moves into flowering mode. It bolts.

Lettuce plants are annuals, meaning they have a one-year life cycle. In that one year they flower and make seed.

So your bolting lettuce is a normal thing.

Bolting lettuce plants can get quite tall!

What Bolting Lettuce Looks Like

Bolting lettuce looks a bit like plant yoga as the centre of the leaf rosette begins to stretch upwards. Next, the now-lanky lettuce sends up a flower stalk.

Meanwhile, the leaves become bitter and tough.

What Makes Lettuce Bolt?

Bolting is normal. But lettuce plants don't bolt according to the calendar. A lettuce plant bolts because it's triggered by what's going on around the plant.

Here are triggers:

Heat

Dry conditions

Long days

As you see, lettuce bolts as we get normal summer weather. But you can still enjoy lettuce leaves in the summer using the ideas below.

5 Ways to Delay Lettuce Bolting:

Here are ways to keep growing these cool-season plants during the summer for continuous supply of salad greens:

Choose Slow-to-Bolt Lettuce Varieties

Some lettuce varieties don't bolt as quickly in summer weather. As you're shopping for lettuce seeds, look for a "heat-tolerant" or "bolt-resistant" lettuce variety.

Provide Shade for Summer Lettuce

When conditions are cooler and moister in the spring, lettuce does well in full-sun locations.

But as things heat up, give your lettuce some shade. When it's shadier it's also cooler and there's often more soil moisture.

There are a few ways to grow a shaded lettuce crop in the summer:

Growing lettuce in pots placed in a shady location.

Grow lettuce underneath taller crops that shade it. I grow lettuce underneath staked tomato plants.

Put up a mini hoop tunnel with shade cloth over top of the lettuce.

Grow vining crops such as cucumbers over an A-frame—and grow your lettuce in the shaded space underneath

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Mind the Moisture

Well-watered lettuce doesn't bolt as quickly. Water regularly.

If you're growing in rows and can mulch around plants, a generous layer of mulch helps to hold in moisture.

Don't Overcrowd

Prevent lettuce from bolting quickly with heat-resistant varieties, ample moisture, shade, enough space—and a shock treatment!

Stress can cause lettuce to bolt sooner. When lettuce plants are tightly packed into a garden, there's less space for roots, less space for leaves to grow—and less moisture. These stresses can make lettuce plants bolt sooner.

When I sow a bed of lettuce, I seed fairly densely. But as the little lettuce plants grow, I pull out some of the small plants as I harvest. This allows more space between remaining plants.

Shock Treatment

A little shock can temporarily derail the plant's readiness to bolt. Dig up and transplant a few of your perfect heads of lettuce to give yourself a few extra days of lettuce harvest.

A Non-Bolting Lettuce Alternative

Here's another idea for you: Grow a leafy green that won't bolt.

Swiss chard has a two-year life cycle. It's a "biennial."

That means that for the whole first year, the plant makes leaves. It only bolts in its second year.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Let a Few Lettuce Plants Flower

Lettuce producing seeds that float around the garden if left long enough. Grow your own lettuce seed—and attract birds to the garden with lettuce seed.

When the lettuce begins to bolt, I remove most of the plants. But I keep a few.

Here's why to keep a bolting lettuce plant:

Grow your own seeds. You can save the seeds to plant later, or, you can allow the wind to move the floating seeds around your garden.

Attract finches to the garden. I love to watch gold finches swoop in and land on the tall lettuce seed head to dine on the seeds.

FAQ: Bolting Lettuce

Can you eat bolted lettuce?

It's not toxic, but it's hardly palatable. But if you enjoy something that combines bitter and tough, give it a try.

Can you prevent lettuce from going to seed?

Short of killing the plant, you probably can't derail that one-year life cycle that terminates with seed.

But if you follow the steps above, you can delay bolting and seed formation.

What other leafy greens bolt?

Arugula, spinach, cilantro, bok choy, and mustard are common leafy greens that bolt.

More Vegetable Gardening Ideas

Articles

Courses

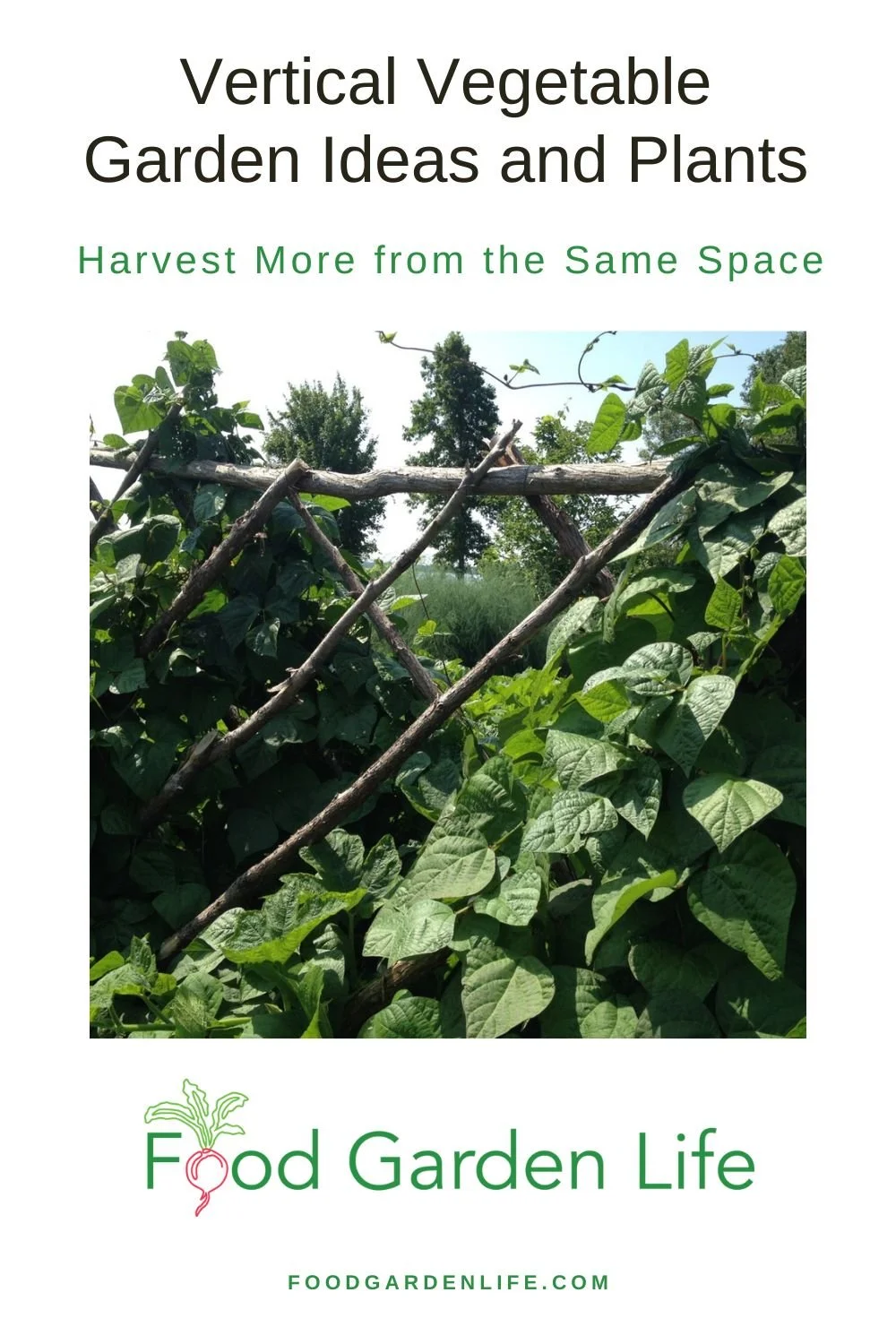

Guide: Vertical Vegetable Garden Ideas and Plants

Harvest more from the same space with these vertical-vegetable-garden ideas and vertical gardening crops.

By Steven Biggs

Vertical Gardens to Harvest More

Vertical vegetable gardening squeezes more plants into a limited space by making use of space above the ground.

By growing sprawling plants upwards, there’s space on the ground to grow more plants.

Other Vertical Garden Benefits

Along with making it possible to grow more plants in the same space, a vertical vegetable garden has a couple of other benefits:

Vertical vegetable gardens for easy harvests. Less bending, because crops are raised

Vertical Gardens Help Provide Shade. Some crops do better in partial shade during the summer. Leafy vegetables grown on the ground space in the shade of a vertical vegetable garden are sheltered from the midday sun.

If you’re interested in creating more growing space to grow vegetables, keep reading. This article includes vertical garden crops, vertical vegetable garden ideas, and easy-to-work-with materials to make supports and trellises.

How to Add Vertical Crops to a Garden

Vertical Vegetable Garden Ideas

There are many ways to add vertical elements to a vegetable garden.

Look for ready-to-use products if you want to start small. It can be something as simple as a tomato cage to support a vining plant—or a window box for cascading herbs.

There are also lots of creative ways to make your own support structures so that you can grow vertically.

Add Tiers with Containers

Containers are a simple way to fit more plants into a garden. Having different tiers means that the canopies of different crops aren’t competing for space at the same level.

Another advantage of containers is that they make it possible to add a crop to an area where there is root competition from a neighbouring crop.

Fences to Support Vines

Squash growing on a fence as part of a vertical vegetable garden.

Fences can be a great opportunity to grow a vertical garden. If the space next to the fence is paved, consider growing in a container.

Tie tomato plants to a chain-link fence

Run twine along a board fence for cucumbers and other vining plants

Grow strawberries or herbs in planters fastened to the fence

Hanging Baskets and Hanging Planters

Vertical gardening doesn’t always mean training a plant upwards.

It can include plants dangling down. A hanging garden.

There are lots of crop options for hanging baskets. Here are ideas to get started:

Add hanging baskets to vertical vegetable gardens.

Strawberries

Tomato plants

Herbs

Salad greens for hanging baskets in partial shade

Trailing nasturtiums (edible flowers!)

Stakes for a Vertical Vegetable Garden

Staked tomatoes leave space for some parsley plants at the ground level.

When staking a plant and growing it upwards you’re opening up space below for another crop. For many gardeners, the sight of staked tomatoes is familiar. Now picture those tomato plants with lettuce or parley underneath.

Some plants can wrap around or grab onto a stake. Other, such as tomatoes, must be tied to the stake.

Self-Supporting Structures for Vertical Gardens

There are many ways to make self-supporting structures for vertical growing.

Even if a vertical garden structure is self-supporting, it’s a good idea to secure it to the ground with a stake so that it doesn’t topple in strong wind.

Here are a few ideas to create vertical space:

Tee Pees

A-frames

A Row of angled, crossing poles jointed together with a pole laying across the top

Grow food vertically using simple bamboo structures such as teepees and A-frames.

Or make more permanent structures for climbing vegetables using lumber:

Lattice-and-lumber A-frame

Wood frames from which twine can be suspended for vining crops

Wooden A-frames over which vining crops grow; and under which shade-tolerant leafy greens thrive during the summer

Or make ornamental landscape features the double as support for growing crops:

Arbours

Pergolas

Use Plants in the Landscape for Vertical Growing Space

Use plants within the landscape to support vining vertical crops:

Save space by growing squash along a hedge!

Hedge (grow a squash vine along a hedge)

Tree (let runner beans grow into a small tree)

Sunflower or corn as a living trellis

Trellises for a Wall Garden

Trellises are a simple way to add more vertical growing space.

Turn an empty wall into a home for a vining crop

Add height to a fence with a trellis

Cover an unsightly utility pole and make it into a growing space

Vertical Garden Crops Ideas

Here are crops that are suited to growing vertically.

Achocha (a.k.a. Bolivian cucumber)

Achocha is a vining crop that’s easy to grow in a vertical vegetable garden.

If you’ve been frustrated by pests and diseases on more delicate vining crops such as cucumber, try achocha. It’s a survivor.

This vining crop has small pods that are eaten raw when small, and cooked when a bit bigger. (There’s a limit to how big they can get without being too woody, so aim to harvest them while small.)

Beans (pole beans and runner beans)

Both of these vining beans are a great addition to a vertical vegetable garden.

Grow them up trellises, garden structures, and tall fences.

Runner beans do better in cooler, maritime climates—and they tolerate partial shade.

Bitter melon

This vining crop has tendrils. Both fruit and young shoot tips are edible. Tolerates partial shade.

Burr Gherkin

Burr gherkin is a vining crop that’s easy to grow in a vertical vegetable garden.

Spiky little cucumber relatives with a citrusy taste. Tasty fresh, and good for pickles too. Vines grow like cucumbers.

Cucamelon

(a.k.a. Mouse Melon, Mexican Sour Gherkin)

This cucumber relative has smaller leaves and fruit, but is a vigorous grow that easily climbs a trellis.

The small, thumbnail-sized fruit are cucumber-like, with a bit of citrus. Eat fresh, or make into pickles.

Cucumbers

Along with conventional cucumbers, look for Armenian cucumbers (not actually a cucumber…but a relative). Both make excellent vining crops.

Luffa

While many people think of using mature luffa fruit for the sponge-like scrubbies, the young luffa is edible—like a summer squash.

If you’re in a cold zone, know that this is a heat-loving crop that does best with a long growing season.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Malabar Spinach

(a.k.a Indian spinach, Ceylon spinach, vine spinach)

This vining plant is a spinach in name only. The leaves are thicker and waxier than true spinach. But it grows all summer—and grows well in heat of summer. The red-leaved varieties are quite ornamental.

Melons

Worried that you can’t grow melons and watermelons vertically because they’re too heavy? Don’t worry. Just make a sling to support the fruit.

Peas

If you've grown bush-types peas, you might not think of them as a vertical vegetable. For vertical gardening, get vining-type peas, which grow 6-8’ tall. ‘Tall Telephone’ is a well-known variety. (Remember, tendrils and shoot tips are edible too!)

Squash

Be sure to grow a vining squash variety, as many of the summer squash have a bush-like growth habit.

And…remember that you can eat more than just the squash fruit. Shoot tips are edible too.

Find out about eating squash tips and other lesser-known edible plant parts.

If you’re growing large winter squash, give extra support with a sling.

Tomatoes

Grow “indeterminate” tomatoes (a.k.a. vining tomatoes) for training upwards. They get taller and taller all summer long.

Most people think of growing tomatoes upwards…but some gardeners also let them dangle down. How about a curtain of tomato vines coming off a low-roofed shed or outbuilding?

Malabar spinach.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Materials for Making DIY Vertical Support Structures

Bamboo Poles

Bamboo poles are an easy-to-use material that is widely available.

Use bamboo poles to stake individual plants, or to make trellises and A-frames.

When attaching poles together to create a trellis or support structure, use twine or zip ties. (Just don’t use the bright yellow zip ties like the ones in the photo below…clear ones are much less noticeable!)

Branches

For a natural look—and for good economy—nothing beats branches.

Twine

Natural-fibre twines such as jute and sisal readily break down when added to the compost pile or buried. They work well for tying plants and for making structures such as teepees.

If the twine will support a lot of weight (e.g. an 8’ high tomato-laden vine by the end of the season) consider something stronger. Either a thicker natural twine, or a synthetic twine.

Lumber

Like branches, lumber can often be scavenged for free.

The one caveat: Don’t use pressure-treated wood. It contains copper compounds.

Lattice

Looking to combine vertical growing with some privacy shields? Lattice could be a building material to consider.

A sheet of lattice usually bends when stood upright, so plan to frame it with wood so that it doesn’t bend.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Metal Stakes

Metal stakes last a long time!

T-bar stakes. Strong. Plan to use a post driver or a sledge hammer to drive them into the ground

Iron rebar. Thinner than T-bars, meaning that if the soil is moist, it can often be pushed into the ground.

PVC Pipe

Use PVC pipe to create supports for your vertical vegetable garden. It's readily available,

Looking for ways to connect horizontal poles to an upright T-bar? Stick a PVC plumbing tee-join on top of the T-bar – and now there are holes on either side into which to slip a horizontal pole.

Wire Mesh

There are a few types of wire mesh available; not all of them at garden centres. See what you can find at hardware and building-supply stores. And if you’re in a rural area, farm-supply stores often carry a good selection of wire.

To get you started as you think about using wire mesh…

Chicken wire. Easy to cut with tin snips.

Wire mesh to reinforce concrete. (A.k.a. remesh) Not galvanized like some other types of wire mesh, so it quickly takes on the patina of time and blends into the landscape. Tin snips won’t cut through this…plan for bolt cutter or a hack saw.

Hardware cloth. If you want closely spaced mesh that offers a visual shield, this can be an option. Cut with tin snips.

Cattle panels. Often galvanized. The spacing in the lower couple of courses of wire is often less than the other courses. More bendable than the mesh used for concrete—so if you’re looking to make an arch, a better choice.

Rolls of livestock fencing. Various gauges or wire and hole size available.

When buying mesh, think about this:

Do you want a galvanized product or not? Shiny obvious metal, or oxidized and less noticeable?

How will you transport it? Rolls can easily fit into the trunk of a car…but if you’re buying sheets of cattle panel or concrete mesh, you might need to put them on a roof rack (or track down a friend with a pickup truck!)

More Vegetable Gardening Information

Courses

Guide to Fruits and Vegetables that Grow in Shade

Looking for fruits, vegetables, and herbs that grow well in a shady garden. This article has partial-sun crop ideas for you.

By Steven Biggs

Shade-Tolerant Vegetables and Fruits for Home Gardens

But there are fruits, vegetables, and herbs that do nicely in a shady garden.

Not enough sunny real estate in your yard? Partial sun? Light shade? You're not alone.

When I first landscaped my place, my neighbour Bob asked, "Steve, why is your patio so far from your house?"

Here's what I told Bob:

"It's all about the vegetables. Direct sunlight for my vegetables, and the shady spot for the patio," I told him.

House, garage, fence, shed, tree, hedge...there are lots of things around a home that cast a little shade. And not all fruits and vegetables grow well in shade.

Lots of crops need "full sun" (6-8 hours of direct sunlight every day) to grow well.

But there are fruits, vegetables, and herbs that do nicely in a shady garden. This article has partial-sun crop ideas for you.

Perfectionism meets Shade Garden

Don’t have a sunny field for growing vegetables? That’s fine, there are many shade-tolerant crops.

Before we get to shade-tolerant crops, let's start with the elephant in the room.

Perfectionism.

Many seed packets suggest full sun...and many yards don't have full sun. You might be contrasting your shaded yard to bright, sunny fields of vegetables.

Your space doesn't compare...

So what?

So what if your plants don't look as good as what a commercial grower would grow! If you're a home gardener, you're just growing edible plants for yourself, not to sell at market.

When I needed more growing space, I decided to reclaim the end of my ridiculously long driveway as a straw-bale garden that I could pack full of tomato plants and pole beans. (Find out more about straw-bale gardens here.)

My driveway garden is in partial sun, nestled between two houses.

The driveway is nestled between two houses. It gets less than six hours of sun exposure. But it’s better to have some less-than-perfect tomato plants on that driveway and get a decent harvest than to have no tomatoes from that driveway.

Five hours of sun isn't perfect. So what? The results are still quite satisfactory.

A vegetable garden is a great cure for perfectionism. In home gardens we often have less-than-perfect conditions. So what!

A Word on Shade

Not all sun (and not all shade) is created equal. Here are things to consider as you look at the shady spots and sunny spots around a yard:

Dappled shade. Think of the shade under a locust tree, spotted with little flecks of light.

Deep shade. This is where no light is gets through or is reflected, like next to buildings or under trees with dense canopies. Norway maple...I'm talking about you!

Afternoon shade. A.k.a. morning sun...and morning sun isn't as strong as afternoon sun.

Morning shade. Or afternoon sun.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Choosing Crops that Tolerate Partial Shade

Start with Leafy Greens

Start with leafy greens when gardening in partial shade.

The reason partial shade is fine for leafy greens is that we're not trying to grow a perfect crop: All we want is the leaves. We're not growing for flowers or fruit or seeds.

(And with a bit of shade, leaves are often bigger!)

Many of the crops we grow as leafy greens (e.g. arugula, lettuce, and spinach) have a short life cycle that's less that the length of the growing season. And that means that at some point they give up making tender leaves, and send up a flower stalk. (This is called "bolting.")

Bolting happens more quickly in hot, sunny locations. By growing leafy green crops in partial shade during intense summer heat, they'll bolt more slowly, and make tender leaves for longer time.

So even if you have a north-facing garden area or planter, grow leafy vegetables.

Here’s more about how to prevent lettuce from bolting.

Leafy Vegetables That Grow in Shade

Here are a few leafy greens that do very nicely in partial shade:

These lettuce plants will do well in this dappled light over the summer. It’s cooler than in direct sun.

Amaranth

Arugula

Beets (for the edible leaves…don’t expect as much from the roots as you get in a sunny location)

Bok choy

Claytonia

Collards

Corn salad

Cress

Endive

Kale

Lettuce

Mizuna

Mustard greens

Spinach

Swiss chard

If you have a favourite leafy green that's not on this list, try it. Leafy greens usually do very nicely in partial shade.

One more crop that I don't think of as a leafy vegetable (even though we eat the leaves) is green onions. With green onions, we're not trying to encourage bulb development...we're just trying to get tender leaves. So partial shade is fine.

Try Vining Crops in Partial Shade

Grow vining crops that can grow upwards and into the sunlight.

If you have a partially shaded area where vining crops could grow up into a sunnier location, this can be a useful strategy.

Train them up a trellis, arbour, hedge, or tree into sunnier conditions.

Cucumbers. They also grow respectably well in partial shade. I've grown them in afternoon sun, up a trellis on the west side of a garage with very respectable results.

Squash. Like cucumber, they grow respectably well in partial shade. I've grown them along a semi-shaded cedar hedge, and was delighted to find the hedge studded with squash at the end of the season.

Pole and runner beans. The year I grew runner beans up a tee-pee underneath my apple tree they grew right up into the tree above...and those scarlet flowers looked great amongst the green apples!

Vining Peas. Some pea varieties are bush-like, but if you want a vining crop to grow up into a sunnier space, look for vining peas. And with peas, you can also harvest and eat young shoot tips and tendrils.

All of these vining crops work well for vertical gardening. Find out how to make a vertical vegetable garden.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Beyond Leafy Vegetables

I already told you about my 5-hour-a-day driveway tomatoes.

If you're experimenting with other sun-loving vegetables in partial shade, just expect them to have lanky growth and lower yield. And at a certain level of sunlight, you won't get enough to make it worth your while.

But if you don't try, you won't know.

Herbs for Partial Shade

Lovage is a perennial herb that tolerates some shade.

There are many herbs that grow in shade. Here are my favourites:

Chives

Cilantro

Dill

Lemon Balm

Lovage (this perennial herb lives in my semi-shaded perennial border)

Mint (see Full Shade, below)

Parsley

Fruit Crops for Partial Shade

When growing fruit in partial shade, take the same approach we do with veggies. Just adjust expectations accordingly.

Here are fruit crops that grow well in partial shade:

Choke cherry. Often found on the forest edge, where there's some shade. (Find out about 5 Types of Cherry Bushes for Edible Landscapes.)

Currants. My favourite. Here’s an article about how to grow currants.

Elderberry. Often found on the forest edge, where there's some shade.

Gooseberry. They take the same low-light conditions as currants.

Hardy Kiwi Vine.

Pawpaw. While young pawpaw trees benefit from shade, best fruit production is in full sun. But they fruit well in partial shade. No surprise as that's where you often find them in the wild.

Serviceberry. An understorey tree often found on the forest edge, where there's some shade. My favourite member of the serviceberry clan is the Saskatoon bush. Find out more about the Saskatoon bush.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

What About Full Shade?

This rhubarb plant is in partial shade, but I’ve seed decent rhubarb patches even in full shade.

If you have a space without any direct sunlight, reflected sunlight, or dappled sunlight, your crop options are more limited.

Here are ideas for you:

Mint is an invasive plant that I normally only grow in containers. But in full shade, mint can be your friend. This is the one situation where I plant mint in the ground.

Rhubarb can do very nicely in full shade. My friend Chris had a lovely rhubarb plant that graced the edge of his shady pond...it looked quite tropical with the big leaves! Find out how to force rhubarb indoors over the winter.

Currants and gooseberries are a good fit underneath bigger trees. My neighbour Mr. Browne had a currant bush growing in the full shade of an apple tree...and that bush faithfully fruited year after year, albeit not as much as it would have in a sunnier spot.

FAQ Shade Tolerant Crops

Pin this post!

What is the best shade tolerant vegetable?

Parsley. Hands down. Because it's delicious, tolerates a wide range of conditions—and it’s very ornamental. I’ve used it as a flower-border edging plant on the north side of a house. The curly-leaf types add great texture, and last well into the fall in cooler temperatures—until there's a hard freeze.

You might be saying, "But it's a herb." I've heard people argue it's a herb, others say it's a vegetable. In the quantities I use in my salads, I'm using it as a veg.

Can vegetables get too much sun?

Yes. Too much sun and too much heat cause many of the leafy greens to bolt quickly. They do better in shady areas in the heat of summer.

What is the difference between partial sun and partial shade?

If you read different sources, you'll come up with various definition.

To me, it's semantics. It just means less than full sun. I guess it depends whether you're the type of person who sees the glass as half full or half empty!

Parsley does very well in shady locations. And it’s a great plant for adding texture to a garden!

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More Articles on Growing Crops

Articles about Growing Vegetables

Find out how to stake and support tomato plants.

Courses

Want to Water Less and Harvest More? Try Sub-Irrigated Planters

Find out how to make your own sub-irrigated planter (a.k.a. self-watering container).

By Steven Biggs

Wilted by Noon

When I first started container gardening on my garage rooftop, I watered every morning. But in the heat of summer, my plants were parched and wilting by noon.

A sub-irrigated planter is an excellent way to solve the problem of parched plants. We want to prevent wilting, because it’s a sign of stress. Drying out is a stress for the crop.

And that stress can delay (or reduce!) your harvest.

Consistent soil moisture is best. Not sopping wet. Not dry.

And that’s where a sub-irrigated planter helps: It keeps the potting mix consistently moist, but not too wet.

This sort of planter is also known as a SIP, a self-watering container, or a self-watering planter.

Keep reading and I’ll explain how a self-watering system works and how you can make your own.

What are Sub-Irrigated Planters?

Sub-irrigation planters are simply planters with a water reservoir at the bottom. The reservoir is right under the soil.

Through capillary action, water wicks up through the potting mix, giving plant roots a consistent supply of moisture. Then, as the plants use water in the soil (creating a moisture gradient) more water wicks upwards from the reservoir.

There are many commercially produced sub-irrigated planters available. Some are fairly basic and resemble a normal container. Others have a gauge that shows the water level in the reservoir.

Self-Watering Planters vs. SIPS vs. Sub-Irrigation Planters

These are all different terms used to describe the same thing: Containers that have a water reservoir below, so that moisture can wick up into the soil.

By the way, they are not truly “self-watering.” The gardener must still fill the reservoir. (If you like do-it-yourself projects, you can automate this with irrigation, see below.)

Benefits of Sub-Irrigated Planters

First, though, let’s look at the benefits of these self-watering containers.

Less waste:

There is less waste of water and fertilizer because it's a closed system, with less runoff

Higher yield because:

A continuously moist growing medium means the plant has no water stress (plant growth can slow, or flowers drop when the plant is under stress…)

When gardening in a container, the growing medium is warmer than soil in the garden, and that means that harvest begins earlier

Fewer weeds because:

The soil surface is not regularly moistened from overhead watering, giving dry surface conditions are not as good for weed seeds to germinate

The other reason that the soil surface is not as wet is that the farther you are from the reservoir, the less moist the soil (remember, it's going against gravity!)

Less disease because:

With no overhead watering, there's less splashing of disease organisms from the potting soil onto the leaves

And with tomatoes, SIPS usually solve blossom end rot (which actually is not a disease, but a physiological disorder that's caused by swings in soil moisture)

And the benefit of a SIP system that goes without saying: You spend less time spend watering!

Where to Grow in a Sub-Irrigated Planter

I made a garden on my garage rooftop using sub-irrigated (self-watering) planters.

As with any sort of container garden, a SIP makes it possible to grow on patios, decks, driveways.

You can also use them to grow over top of areas with tree roots or compacted soil.

If you’ve been eyeing up a space next to that water-hungry cedar hedge, this is your solution!

If you’re concerned about soil contamination, making a container garden is a simple solution.

Find out more about soil contamination.

What’s Inside a SIP

Here's what you'll usually find in a self-watering planter.

A water-tight area (the reservoir) at the base of the container (underneath the potting mix)

Something to hold the potting mix above the reservoir area: it could be a false bottom such as mesh, or hollow containers, or tubing

A way to add water to the reservoir (a fill-tube that extends above the soil surface)

A wick (the wick is usually the potting mix itself, but a fabric wick can be used too)

An overflow hole, so that if there's too much water, it can escape

How a Sub-Irrigation Planter Works

Think of how water moves up a sponge. Or put a piece of paper towel in water and watch the water move upwards.

The same thing happens in a self-watering planter.

The water that's stored in the reservoir moves up through the soil.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Plants That Thrive in Sub-Irrigated Planters

Annual vegetable and herb crops do well in sub-irrigation planters.

Avoid plants that are susceptible to root rot when overwatered. (For example, I grow potted lemon trees, and they hate “wet feet,” soil that says consistently wet. Read more about potted lemon trees.)

Potting Soil for Sub-Irrigated Planters

Choose a potting soil with good wicking properties. Do not use garden top soil or sand.

Sometimes this is easier said than done...because you won't find "wicking" on potting soil labels.

(A bargain isn't always a bargain when it comes to potting soil. If you see discounted bags at big-box retailers, be wary.)