Skip the Transplants: Direct Sowing Seeds

Find out how and what to direct seed in your vegetable garden.

by Steven Biggs

Why Direct Sow Seeds?

Ever had transplants that put on the brakes after you move them to the garden?

It’s disappointing.

But a big transplant isn’t always better than a wee seed.

Sometimes, it’s better to plant seeds straight into the garden.

This is called direct sowing (or direct seeding.)

This post tells you how to direct sow, best crops for direct sowing—and simple ways to sow seeds in a home garden.

What is Direct Sowing?

Direct sowing is when we sow seeds directly in the garden.

This is instead of starting seeds indoors—known as growing “transplants.”

Why Direct Sow Vegetable Seeds?

There are many reasons to direct-sow vegetables.

Here are a few reasons:

Pin this post!

Easier (there's no need to care for seedlings indoors)

Less expensive (no need for potting soil or containers)

Less environmental footprint (yeah, your coir-based and peat-based potting soils have an environmental footprint)

Saves indoor seed-starting space for crops that really need to be started indoors

No need to “harden off” young seedlings before planting them in the garden

Some crops don’t transplant well…and don’t bounce back well from transplanting

When Direct Sowing is NOT the Best Choice

Direct seeding isn’t the best choice for all crops, or in all situations.

Here are a few things to consider:

In areas with a short growing season, crops that take a long time to mature are grown from transplants

Slugs and other bugs can devastate small, direct-sown seedlings as they emerge…whereas a larger transplant might get through some insect damage

During hot summer weather, seed germination can be spotty (see below for a summer seed-sowing hack)

In low-lying area, the garden soil might be too wet to plant seeds in the spring

You’re new to gardening and won’t know the difference between emerging direct-seeded crops and the weed seedlings!

How to Direct Sow Seeds

Before sowing seeds, prepare the soil.

Start by preparing the soil ahead of time. When sowing seeds, we want to break up any crust on top of the soil surface, and break up bigger chunks of soil. That way, germinating seeds don’t hit roadblocks.

(Yes, there’s a whole body of work out there on no-dig techniques—and there is a time and place for this…but if you want the best results when planting seeds, prepare the soil.)

Planting Depth

Use the size of the seed as a guide to planting depth. Seed packets usually recommend a depth too.

Plant the seed about twice as deep as it is wide. Too shallow is better than too deep.

But don't feel as if you need to measure and be precise.

If you’re planting seeds into trenches, you can make well-spaced trenches using a garden rake that has pieces of pipe on it.

Like most things in gardening (and life), direct sowing isn't an exact science.

Trench for Sowing Seeds

If you direct-sow seeds in rows, make a trench with your trowel or the corner of a hoe.

Then, place your vegetable seeds into the trench, and cover with soil.

OR, make your trenches by fitting pieces of pipe onto a garden rake!

Poke Seeds in the Soil (Planting Seeds Simplified!)

This is low-tech and might be laughable to a commercial grower—but in a home-garden setting, can be a simple approach to direct sow seeds!

I drop large seeds into place, and then just poke them into the soil. Then I scuff the soil to fill the holes.

Poking works well for larger seeds that you can easily see:

Poking large seeds into the soil is a simple way of planting seeds.

Peas

Beans

Beets

Swiss chard

Squash

Zucchini

If you’re planting a whole block with seeds, as I like to do with beets and Swiss chard, you can do what I call the “scatter-and-poke” method. Scatter seeds to approximately the spacing you want—and then poke them into the soil. Scuff soil to fill in holes.

(Gardening is a great cure for perfectionism, and the scatter-and-poke approach dispenses with all notions of perfection in a garden!)

Broadcast and Cover

You can sprinkle small seeds such as these carrot seeds by hand, and then cover with soil.

If you’re filling a block or wide row with small seeds (e.g. carrot or lettuce), sprinkle by hand, and then cover with soil.

You might wonder, “Where do I get the soil I’m covering the seed with?” Rake aside some garden soil before you sprinkle your seed in place—and replace it over top of the seed afterwards.

Broadcast and Rake!

I’m always interested in methods that make my life simpler. And raking aside soil before I broadcast seed is a bother.

So I simply broadcast the seed, and then use an up-and-down motion with a hand rake to work some of those seeds into the soil.

Note: There will be some seeds that aren’t at an ideal depth. That’s OK. I’m a home gardener—not a commercial grower. I just seed more heavily to compensate.

Direct Sowing Hacks

Using a broadfork to make straight rows.

Folded paper. Forget the seed-dispensing gizmos for small seed. Fold a sheet of paper in half. Pour seed onto the folded sheet. Now, use a pencil or a nail to dispense individual seeds off the end of this folded sheet. Low tech, yes—but works well.

Broadfork. When my daughter, Emma, wanted side-by-side trial rows of a number of crops, she used the broadfork to make a tidy set of trenches. (The broadfork is normally used to loosen soil…but this works nicely!)

Seed tape. Seeds embedded in a strip of biodegradable paper. Yeah, a bit gimmicky. I don’t use this. But if you’re gardening with kids, or you have shaky hands and can’t easily dispense seed, it can be useful.

Using boards to keep the soil moist for direct seeding in the summer.

Pelleted seed. Small seeds bulked out with a clay coating. Like seed tape, you pay more per seed. But again, could be useful if you’re direct seeding with kids, or you’re having trouble coping with smaller seeds.

Boards. Yup, low-tech boards over summer-sown small seeds can be a life saver. In summer heat, soil can quickly form a crust that seedling have difficulty breaching. But a board over the soil during the germination window keeps the soil underneath moist. No crust.

Web trays. As soon as squirrels see freshly turned soil in my garden, they’re eager to disinter seeds. It’s infuriating. Who would have thought there’s a higher purpose for those horrid plastic webbed trays that the horticulture industry so loves! Inverted web trays over top of your directly sown seeds keep digging varmints at bay.

Direct Seeding by Crop

Take that, squirrels!

Leafy Greens. I grow transplants of leafy green crops such as lettuce, spinach, and Swiss chard. I also direct-sow seeds into the garden.

Why both ways?

So I have a succession of harvests.

(It is also insurance. If weather or pests cause less successful results one way, I have a backup!)

Root Crops. I direct sow all my carrots, parsnips, and beets. These crops can all be direct-sown in the garden early. And they don’t respond well to root disturbance.

“Fruit” Veg. For those fruits that we insist on calling veg—tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant—I grow everything by transplants because I’m in a cold climate and I extend the harvest window with transplants.

Vining Crops. The vining crops in the squash and cucumber clans don’t respond well to root disturbance. So direct sowing is always a good strategy.

(But, like the leafy greens, I hedge my bets and both direct sow and start a few transplants.)

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Courses

Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

Driveway Makeover! 5 Ideas for Growing a Container Garden for Vegetables

A container vegetable garden is a good way to fit lots of vegetable crops into a small space. Find out how to get started.

by Steven Biggs

My Driveway Container Vegetable Garden

Not enough space to grow everything you want? Be creative! A container garden are a great way to fit more vegetables into your yard.

Here’s our driveway container garden. The driveway container garden is a quick, temporary space-making solution so we can grow extra tomato, pepper, potato, summer squash, and chard plants.

In this vegetable container garden, we use straw bales, fabric pots, nursery pots, bushel baskets, and vertical gardening techniques to make the most of the space.

In this post, I talk about these five vegetable container gardening techniques, along with container plants and container garden tips.

Ideas for Your Vegetable Container Garden

Container gardening is part science, and part creativity. There are lots of ways to approach it. Here are five ideas we’ve used to make the most of our driveway for growing vegetables.

1. Strawbale Gardens: Grow Vegetables in Containers that are Biodegradeable

Wetting the straw bales to start the “conditioning” process.

A lot of visitors take a second look at my straw-bale garden and wonder where I put the potting soil. There is no potting soil: The straw bale is both the container and the growing medium. No potting mix required!

The decomposing straw gives plant roots needed air while retaining moisture…like a big sponge.

By the end of the season, when we pull apart a bale, the inside is dark and crumbly. It’s already partially composted and perfect to use as mulch on our gardens. Then, we start again with new bales the following year.

We plant the top with tomato plants and leafy greens. Then we put bush beans on the sides of the bales.

Important: If you’re starting with new, fresh, dry bales, the first step is to get microbial activity underway by watering them and feeding them. This step is called “conditioning.”

Find out more about straw-bale gardening.

2. Bushel Baskets: Growing Vegetables in Containers that are Repurposed

Container vegetable gardening with repurposed stuff! Potatoes growing in lined bushel baskets.

We often have extra bushel baskets from our fall cider-making. So we use them for growing potatoes. (We can’t grow potatoes in our back yard because our neighbour’s black walnut tree gives off a compound that kills them.)

We line the bushel baskets with plastic bags so that the potting soil stays moist longer and so the bushel baskets won’t decompose as quickly. (We poke drainage holes in the bottom of the bags!)

There are lots of repurposed items that work well as containers. Here are a few ideas:

Milk crates. I’ve used these in previous gardens. Just cover the openings on the side and bottom with newspaper or cardboard, so the soil doesn’t escape.

Old wheelbarrow. A friend uses an old wheelbarrow as a driveway planter.

Wash basins. I have neighbours who use metal wash basins as vegetable garden planters. (Make sure to drill drainage holes in the bottom.)

3. Fabric Pots: Garden in Pots that are Moveable

Fabric pots are moveable, and a great way to start container gardening.

These pots are widely available. What we like about them is that they have handles so we can move them aside if we need to move anything large along the driveway.

I’ve seen impressive rooftop container gardens created with fabric pots. While some gardeners use drip irrigation to keep the soil consistently moist, a more simple approach is to put a saucer underneath; as the potting mix begins to dry, water in the saucer wicks upwards.

4. Fence: Grow Vegetable Plants on Surrounding Features

We train tomato plants up the twine that is dangling from the top of the fence.

Sometimes it’s possible to squeeze more crops into a space by growing some of them upwards—a concept that’s often referred to as “vertical gardening.” In the case of our driveway, there’s a wonky board fence that I like to hide with a wall of tomato and squash!

We plant tomatoes next to the fence, and then train them up twine suspended along the fence. We also grow squash vines along the fence—well past where the garden is.

Idea: I’ve also grown squash along hedges and up trees. Because the vines roam around, there are lots of vertical-gardening possibilities.

Here’s more about vertical gardening.

5. Nursery Pots: Figs Growing in Containers

Next to my garage is my potted fig “orchard.” It’s a collection of potted fig plants growing in nursery pots. These fig trees spend the winter in my garage.

Nursery pots are an inexpensive way to start container gardening. Talk with garden centres and arborists—you can often get them for free or very inexpensively.

If you’re interested in growing figs in a cold climate, here’s more about how to do it.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Plan Your Container Vegetable Garden

Choose the Location

If you’re thinking about a container vegetable garden but don’t know where to start, choose your location first.

Then, once you’ve decided on a location, you’ll know how much sunlight you’re dealing with. Remember that full-sun crops such as tomatoes can do respectably well in partial sun. (This is not something a commercial market gardener would do…but if you’re a home gardener, conditions often aren’t perfect.)

Something else to think about is access to water. Is there a tap or hose nearby?

Choosing Container Plants

When it comes to choosing container gardening crops, a good starting point is things you like to eat.

Then, think about crops that do well in containers. Most vegetables grow well if a container is big enough, but some crops are more practical than others.

For example:

Pole beans are great if they're next to something they can grow on, but, otherwise, bush beans are more practical because you don't need to make a trellis.

Parsnips and Brussels sprouts take the whole summer and fall to mature. Instead, look for crops that mature more quickly, like carrots and carrots.

Here’s a list of best vegetables to grow in pots.

If the location is shady, here’s a list of crops that grow in shade.

Consider Containers with Reservoirs

A key to success—and common reason for failure—with container vegetable gardening is watering. When the soil in containers regularly dries out, your vegetable plants put on the brakes. Growth stalls. Or, even worse, your plants skip straight to flowering before they're big enough.

Pin this post!

(When you’re looking for bargain plants at a big-box store and see what looks like a bonsai cauliflower plant that’s only six inches tall, chances are that the plant got parched too often…and that stress made it flower before its time.)

If the potting soil is consistently moist, your crop will be miles ahead. It makes a big difference.

You can keep the potting mix consistently moist with what’s called “sub-irrigated” pots. This is just a fancy way of saying a container with a reservoir. As the potting mix begins to dry, water from the reservoir wicks upwards, keeping the soil continuously moist.

This sort of container is widely available—but you can easily make your own.

Find out more about sub-irrigated (a.k.a. self-watering) pots.

More Container Ideas

If space is tight, small containers might be your only option. I've made herb container gardens by dotting potted plants on a staircase.

Don't forget window boxes. Although they're shallow, they work well for shallow-rooted crops such as leafy greens.

Hanging baskets are a great way to fit more vegetable plants into your container garden.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your container-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Prevent Leggy Seedlings and Grow Vegetable Transplants Like an Expert

The best way to solve the problem of spindly seedlings is to prevent them from getting that way in the first place. Find out how.

By Steven Biggs

Your Seedlings are Leggy? Keep Reading!

If your seedlings are doing the downward dog, this post is for you.

When young seedlings are so fragile that they fold into two, they don’t stand a good chance of success once you transplant them into the garden.

Yet leggy seedlings is a common problem for home gardeners starting seeds indoors. That’s because in a home setting, conditions are often less than ideal.

But there’s good news.

Even if you don’t have perfect conditions—even if you don’t have a greenhouse—you can grow healthy seedlings that will thrive. It’s just a matter of setting up your seed-starting area so you can give small seedlings:

An appropriate temperature

Enough light

A suitable potting soil

Combine these with a suitable container, and you’re away to the races. You can grow strong and healthy plants.

This article tells you how much light you need, what you need to know about temperature, what to look for (and avoid!) in a potting soil, and how to choose a suitable container. Get these four things right, and you’ll prevent leggy seedlings.

Heat to Sow Seeds Indoors

Warmer than room temperature to germinate, cooler than room temperature after germination.

If you see different seed-starting temperature recommendations for different crops, don’t sweat it. You’re probably starting all of your different crops in the same indoor space anyway.

Here’s the big picture, a simple way to think about temperature:

When you start seeds indoors, a temperature a bit above room temperature is helpful for faster, uniform germination

Once your seeds germinate, a temperature slightly cooler than room temperature helps to keep your seedlings more compact

Higher Temperature for Germination

Speed up germination with more heat. Seed tray beside a heat duct to speed up germination.

You can raise the soil temperature without turning your house into a tropical conservatory. Just use what’s called “bottom heat.”

Bottom heat refers to heating the soil from below. There are purpose-made heat mats, like heating pads for plants, that go underneath pots and trays. With a heat mat, you’re only heating a small area.

Here are other ways you might be able to give your seeds bottom heat:

Heated floor

Hot-water radiator

An appliance that gives off heat (my former beer fridge was always warm on top)

In a previous house, I put seed trays beside basement heat ducts (over top of my wine rack!) to get seeds to germinate quickly. They sprouted seedlings faster than the trays in a cooler location.

Hold in Heat

Along with heat from the bottom, hold in heat and keep the humidity higher during the germination period. There are commercially available humidity domes for trays, or you can use clear plastic bags or cling wrap.

Cooler Temperature for Growing

Once seeds have germinated, a cooler temperature helps to develop sturdy stems. So remove the heat mat if you’re using one, and if you’re using a cover, set it ajar to let out some heat and humidity.

I grow seeds in a basement room with the heat ducts closed. It’s slightly cooler than the rest of the house and the temperature works well for raising seedlings.

Sufficient Light

Insufficient light is one of the things that will cause lanky seedlings.

There's a wide variety of grow lights available for home gardeners. But if you’re growing vegetable transplants indoors, you don’t need fancy grow lights. That’s because you’re not trying to grow the crop indoors for its entire life cycle.

All you’re trying to do is to get a healthy seedling to transplant into the garden. And once it’s in the garden, it gets full sunlight.

Grow Lights

Adequate light is important; but there’s no need for perfect light because seedlings get full sunlight when moved to the garden.

I still use fluorescent lights because that's what I have and I'm on a limited budget. You can buy fancy schmancy lights; there’s no need.

If you’re using artificial light, consider the distance of the seedling from the grow light. Some grow lights have adjustable lights that can be moved close to seedlings, and then moved up as seedlings get taller.

If, like me, you don't have that option, place something under the seedlings to raise them up, closer to the light source. (Mandarin orange crates work well in my setup!) As the plants get bigger, lower them so they’re not touching the lights.

Natural Light

If you’re using natural light, the brightest windows are usually south-facing. One challenge is that south-facing windows can be hot. Warmer temperatures can cause leggy seedlings. A simple solution to this is to place a fan in the area to disperse the heat.

Soil

Even with good light and a suitable temperature, if you have poor-quality soil, your seedlings might flop!

When it comes to soil, the top two things to think about are:

Use a light soil with lots of air space to allow excess water to drain and small roots to grow

Choose soil that’s free from pests and diseases

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Disease in Potting Soil

Little seedlings are delicate and they're vulnerable to attack by disease. In a seed-starting environment, the most common disease is what’s called “damping off” disease. This fungal disease can come with the soil—so one of the easiest ways to prevent the disease is to use soil free from damping off.

Here’s how to lessen the chance of damping off:

Don’t reuse potting soil for starting seeds (unless you’re planning to heat sterilize it)

Don’t use garden compost for seed starting; it has more microbial activity—which is great in the garden—just not ideal for indoor seed-starting

Potting Soil Shopping Tips

Big bales. It’s buyer beware with potting soil. Some potting soils are great…some suck. The large compressed bags (a.k.a. bales) that are sold to commercial growers tend to have consistently better quality because commercial growers are more discerning. Big bales are also much better value. They’re compressed, and often quite dry—so also less likely to have eggs of pesky fungus gnats.

Finely-ground potting soils. There are seed-starting potting soils that are more finely ground, the idea being that big particles can get in the way of small seeds. This makes sense in a commercial setting where uniform, perfect germination is a must. It’s absolutely unnecessary in a home-garden setting. Don’t waste your money.

Skip the meal deal. Seeds germinate and start to grow using energy stored in the seed. Don’t buys soil with added fertilizer; it can actually burn tender seedling roots.

And…If you see soil on special at a big box store for a couple of bucks, remember that a bargain isn’t always a bargain.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Containers

When I worked in the horticultural supply industry we sold various seedling trays, pots, the “cell packs” used in commercial seedling production.

Many of these are available to home gardeners, though not necessary.

The key things to think about with containers:

Drainage holes to allow excess water to drain

Not contaminated with damping off disease (see Reusing Pots and Trays, below)

Plug trays for starting seeds indoors. Not necessary, but useful when you grow lots of the same thing.

Container Type and Size

If you’re growing a lot of one type of seed, you might like to have containers that are the same size because it simplifies watering. When my daughter raised hundreds of tomato seedlings, I got her what’s called “plug trays” so she could grow lots of small plants in our small space. They all had the same amount of soil, and dried out at the same speed.

I don’t use the expanding peat pellets. I think they’re gimmicky.

Use What’s in Your Recycling Bin

I am a big fan of scouring the recycling bin for seedling pots. For example:

Yogurt containers

Mandarin orange crates (my favourite for lettuce seedlings)

Tubs for mushrooms

Using a mandarin orange crate to grow tomato seedlings.

Tips when using recycled containers:

The volume of soil in different containers will vary—so water accordingly

Put holes in the container for drainage

Reusing Pots and Trays

If you're reusing pots and trays, it’s a good idea to first sterilize them to prevent damping off disease. That’s because any soil crusted on the container from the previous year can harbour the disease. If you haven’t had damping off disease in the past you might be OK…but personally, I don’t risk it. So I sterilize them.

When damping off disease attacks seedlings, it can wipe out a whole tray in just a day or two. It can be quite devastating.

Cell packs drying after washing and sterilizing to prevent damping off disease on seedlings.

Here’s what I do to sterilize containers:

Soak containers in water

Scrub off any crusted soil

Place them in a solution of 10 parts water with one part bleach

Let them air dry

What About Fibre Pots?

There are a few types of fibre-based biodegradable pots. Recently I saw some made from cow dung! Some people make newspaper pots, or reuse toilet paper rolls for seed starting. In principle, you can plant these pots straight into the ground, but there are a couple of caveats.

The pots wick out moisture, away from plant roots…and they can dry out quickly. So watch the soil moisture to make sure that it doesn't get too dry for your seedlings.

Later, when you transplant seedlings in the garden, if the lip of the pot is above the soil level, it'll wick the water away from around the roots, so the soil around the roots can be drier than the garden soil. So tear off the top of the pot—or bury it. That solves the wicking problem.

FAQ – Leggy Seedlings

Can you fix leggy seedlings? Can leggy seedlings recover? Can you fix stretched seedlings?

You can’t correct leggy seedlings...but if the seedlings aren’t too far gone, you can change the growing conditions so that the seedlings grow thicker stems.

Why are my seedlings flopping over? Why is my plant growing tall and skinny?

It can be too little light, too much heat, excess moisture—or a combination of these.

Can I bury leggy seedlings deeper? Can I fix leggy tomato seedlings?

In many cases, no. First of all, very thin stems can easily be crushed. And most seedlings don’t do well when planted deeper than the level they’re been growing at. Leggy tomato seedlings can be an exception—they do well when planted deeper—but it will depend how long, skinny, and delicate the spindly seedling is. Better to avoid the leggy seedlings in the first place!

Find Out About About Seed Starting in this Podcast

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your food-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Vegetable Seeds

More on Growing Vegetables

Vegetable Gardening Articles and Interviews

For more posts about how to grow vegetables and kitchen garden design, head over to the vegetable gardening home page.

Vegetable Gardening Courses

Want more ideas to make a great kitchen garden? We have great online classes that you can work through at your own pace.

Ripen Green Tomatoes to Extend Your Harvest

Find out how to ripen the green tomatoes that you still have in your garden, by picking them before the first frost, and bringing them indoors.

By Steven Biggs

How to Ripen Green Tomatoes Indoors

You can eat homegrown tomatoes through the winter. No greenhouse needed.

I’ve even eaten my own homegrown, “fresh” tomatoes in April. These are tomatoes I picked green the previous October, just before the first fall frost killed the plants. Then, I ripened them indoors.

You don’t need special conditions to ripen your green tomatoes because unripe tomatoes that have reached a “mature” size (nearly the final size) will keep ripening after they’re removed from the plant.

You can prolong your tomato harvest for weeks – even months.

Keep reading for pointers on picking, storing, and using your green tomatoes in the fall.

How do they Taste?

A plate of tomatoes picked green and ripened indoors.

A vine-ripened tomato from the garden has better flavour. That’s because tomatoes ripened on the vine in the garden develop more sugars and acids.

But a green tomato ripened indoors can have a respectable flavour – and it’s certainly far better than the insipid, mealy excuses for tomatoes found at grocers over the winter.

When to Pick Green Tomatoes for Indoor Ripening

Pick your green tomatoes before the first frost in the fall. Tomatoes exposed to frost get mushy and don’t store or ripen well indoors.

I pick tomatoes that are a mature size, as well as small, undeveloped tomatoes.

What to Pick

I pick everything:

I leave tomatoes that are already colouring up on the kitchen windowsill.

Tomatoes that are a mature size to ripen indoors.

Tomatoes that are small and not fully developed to cook or use in preserves (see my green tomato mincemeat recipe below).

How to Harvest Green Tomatoes

I pick larger tomatoes individually, leaving a small bit of stem attached. The reason that I like to leave a bit of stem attached is that with some tomato varieties, it’s easy to tear the skin while trying to remove the stem.

I leave cherry- and grape-type tomatoes on the stem and harvest the whole cluster.

Another approach is to harvest the whole plant. Cut off entire branches – or even cut off the stem at ground level, leaving the unripe green tomatoes on the plant.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

You Control the Ripening Speed

Small tomatoes that are not close to the final size won’t ripen well, but can be used in the kitchen.

Mature tomatoes give off ethylene gas, which causes them to ripen to ripen more quickly. All we have to do is tweak how much of this gas stays around the tomato.

You can stagger the ripening of your green tomatoes using two things:

Temperature. At warmer temperatures ripening happens more quickly.

Ethylene gas. This is the gas the mature tomatoes give off – and which stimulates ripening. If you want to speed up ripening, let the gas accumulate around the tomatoes. If you want to slow down ripening, allow air movement so the ethylene disperses.

How to Ripen Green Tomatoes

I lay out my green tomatoes in plastic trays lined with newspaper.

You don’t need sunlight to ripen green tomatoes.

There are a number of ways to ripen green tomatoes indoors. I lay out my green tomatoes in plastic trays lined with newspaper. (The newspaper prevents smaller tomatoes from falling through the holes; and absorbs juice from any tomatoes that rot.)

I keep the tray in a cool room in my basement. As tomatoes start to show colour, I bring them up to the kitchen to put on my windowsill, where it’s warmer – and where I monitor them more closely as they finish ripening.

If you want to speed up ripening, just capture some of the ethylene gas by putting the tomatoes in an enclosed space. Here are ways to capture some of that ethylene:

Speed up ripening by putting the tomatoes in an enclosed space. Adding a ripe apple or banana speeds it up more.

Place them in a closed drawer.

Place tomatoes in a closed paper bag (preferable to plastic, which doesn’t breathe at all).

Lay them out in a tray like I do—or on a shelf—and cover with a sheet of newspaper.

Wrap individual tomatoes in newspaper.

If you’ve left on pieces of stem, just be careful not to let the stem puncture any other tomato.

The Banana Trick

Bananas and ripe apples give off ethylene, so you can put a banana or apple in with tomatoes to provide more ethylene and speed up ripening. (I find I don’t need to do this, they ripen fast enough for me.)

Hanging Tomato Plants

If you’ve harvested entire stems or entire plants, simply hang the stems or plants in a cool, dark area and let the tomatoes slowly ripen.

I’m not a fan of this approach because as the tomatoes ripen, they detach from the stem and…splat!

As tomatoes start to show colour, I bring them up to the kitchen to put on my windowsill.

Varieties Suited to Indoor Ripening

A thick-skinned tomato variety that lasts me until spring.

You can ripen all types of tomatoes indoors, but thick-skinned varieties are best for longer-term indoor ripening.

Thin-skinned beefsteak varieties are more prone to rot. It doesn’t mean you can’t ripen these ones indoors – it just means they’re less likely to last long into the winter.

Green Tomato Ripening FAQ

What else can I do with green tomatoes?

I love green tomato fried in the skillet in bacon fat, sprinkled with salt and garlic powder. Some years I make a green tomato mincemeat. You can also make lactic-acid fermented green-tomato pickles – same idea as sauerkraut and brined dill pickles, except using green tomatoes.

Should I wash green tomatoes after picking them?

I don’t. Some people wash them in a bleach solution to disinfect them. Sounds like a lot of bother to me…and I like to keep gardening simple. I wash them once they are ripe, just before I use them.

Can I ripen green tomatoes indoors in the summer too?

Yes! I’ve had large 2-3 pound tomatoes, and just as they ripen a squirrel came along and ate off a corner. It would have been better to pick these before they were fully ripe, and ripen them indoors.

Can you really get them to last until April?

Green tomatoes with cracks and blemishes often rot, so sort them out of your tomato harvest and cook them instead of trying to ripen them.

Yep! The trick is to grow a “keeper” tomato variety. I grow one that came to me from my Dad’s friend Dino. It’s small and thick-skinned...not the juiciest tomato, not the most flavourful tomato – but I can make bruschetta with my own fresh tomatoes in early spring. Not bad!

What about tomatoes that have cracks or blemishes on them?

Tomatoes with cracks and blemishes will not keep for a long time. If they are close to colouring up, you can try to ripen them – just watch closely so you’ll see if they begin to rot around the damaged area. Otherwise, use these tomatoes in one of your green-tomato recipes.

Want to Store More of Your Own Food?

Storage Crop Ideas for Your Vegetable Garden

Here are 25 storage crops you can grow in your garden.

More Tomato Articles

Tomato Interviews

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles: Growing Vegetables

Courses: Grow Vegetables

Propagate Blackberries by Tip Layering

Propagate your blackberry plants with tip layering.

By Steven Biggs

A Simple Way to Grow Your Own Blackberries

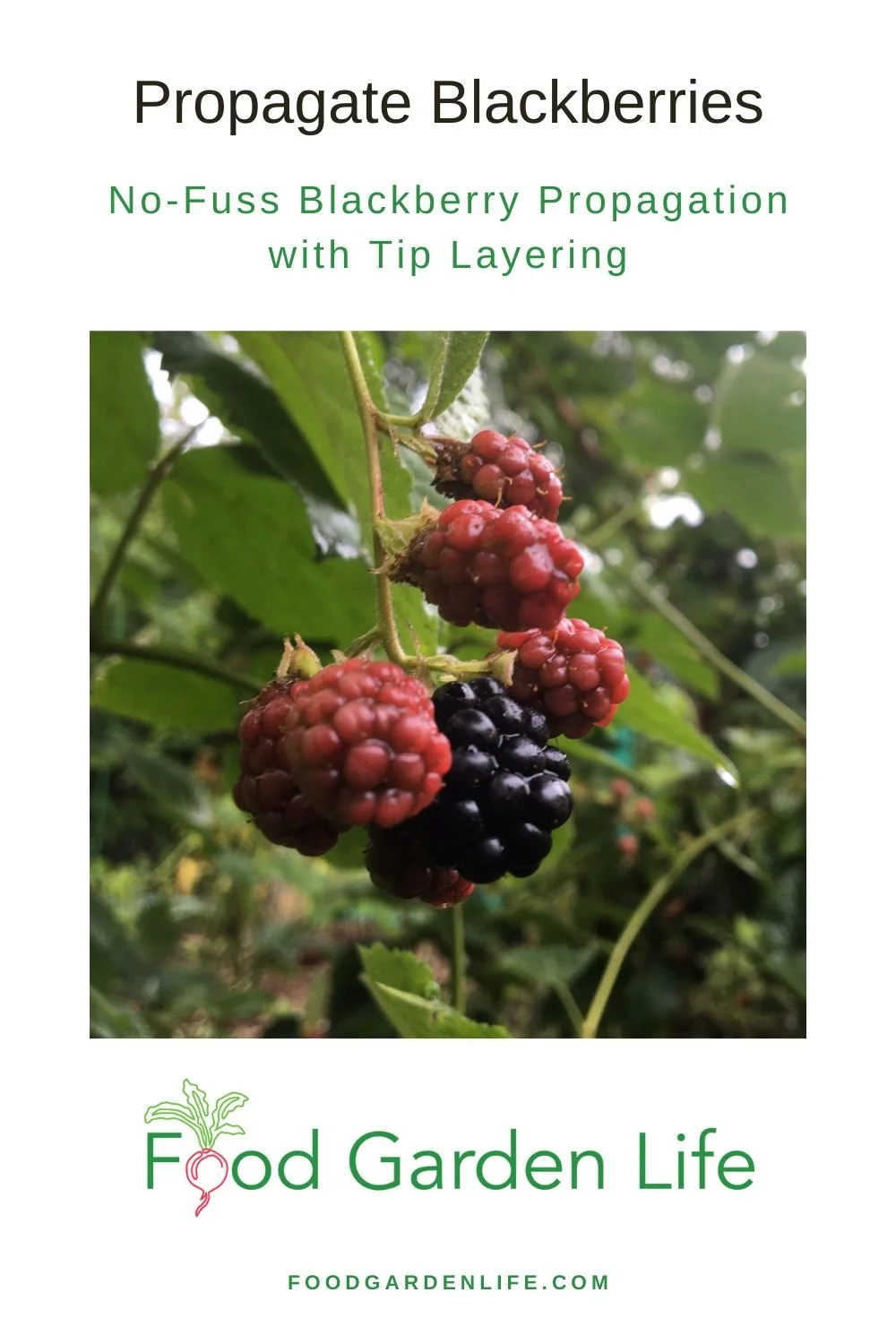

What is the easiest way to make more blackberry plants?

It's called "tip layering."

In mid-summer, as their long, arching canes reach the ground, blackberry plants often propagate themselves by tip layering.

If you want to make more blackberry plants, it’s an easy way to do it. I once tip-layered a single blackberry plant into a 30-foot stretch of blackberries along a chain-link fence!

This article tells you about this simple approach to propagating blackberries.

What is "Layering"?

I once tip-layered a single blackberry plant into a 30-foot living blackberry-plant wall along a chain-link fence.

Layering is when roots form on a stem while it's still attached to a parent plant.

Many plants naturally layer when low-lying branches touch the soil. (I find currant "layers"—rooted currant branches—in my currant patch. Find out more about how to grow and propagate currants.)

Some plants don't layer as easily, and gardeners can help the process by:

Wounding the stem where it will contact the soil

Applying a rooting hormone

Pinning the stem to the ground (or burying a portion of it)

Once it has its own root system, the rooted layer can be detached from the parent plant.

What is "Tip Layering"?

Tip layering is when the tip of a stem touches the soil and forms roots. (It's sometimes called "tip rooting.")

Unlike blackberry stem cuttings, which need ongoing care, blackberry tip layering is a hands-off blackberry propagation method.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

How Blackberry Plants Grow

A blackberry plant has long arching stems, called canes. The canes grow upwards, and when they get tall enough, they start to bend. They keep growing, and the tip of the can will often bend over and touch the ground.

Once the tip of the blackberry cane touches the ground, it will grow roots. This cane has reached the ground and will stop getting longer, and instead form roots.

Once the tip of the blackberry cane touches the ground, it will grow roots. When the roots are well developed, you can cut the cane to detach it from the parent plant, and you now have a new blackberry plant.

Other Cane Fruit for Tip Layering

Purple and black raspberries can also be propagated by tip layering.

(Red and yellow raspberries are different. They send out lots of suckers and grow into a patch. To make more red and yellow raspberry plants, simply dig up plants around the edge of the patch.)

Training to Prevent Tip Layering

Tip layering is an easy blackberry propagation method. But you can have too much of a good thing…

I've seen enthusiastic gardeners inadvertently allow and an impenetrable thicket of new blackberry plants to form!

Where you don't want additional plants, train the canes to keep them off the ground. If you have a fence, simply tie them to the fence. Or put in a few stakes to which you can tie the canes to keep them above the ground.

Pruning Blackberry Plants

One other thing to keep in mind as you grow blackberries is that the canes only live for two years.

Year 1: Stems grow upwards from the base of the plant, and as they get tall enough, arch over

Year 2: The stems produce fruit

So if you want to keep pruning simple, at the end of the growing season, remove any canes that have produced fruit.

FAQ Blackberry Tip Layering

What time of year do you propagate blackberries?

The blackberry canes often begin to tip layer on their own mid-summer, as the canes get long enough to bend over and touch the ground.

Are there other types of layering?

Yes. Along with the basic layering and tip layering we talk about above, there is:

Serpentine (compound) layering, where we make several layers on a long stem by burying several sections of it.

Stool (mound) layering where a shrub or tree is cut to ground level, causing it to send up multiple shoots, which are then mounded with soil. This gives multiple, rooted stems. (It's what I use to propagate my apple rootstock.)

Air layering, where soil or a damp medium is wrapped around an above ground portion of stem to induce root formation. (I sometimes use this if want to root a long, gangly fig branch. Find out more about fig propagation.)

Why grow so many blackberry plants?

For blackberry daiquiris, of course.

More on Growing Fruit

Succession Planting: Here's How You Can Harvest Vegetables Season Long

By Steven Biggs

Succession Crops are the Ticket to an Uninterrupted Harvest

"Succession planting" is when we grow more than one crop in the same space over the growing season. We grow a succession of crops.

As one crop finishes, the succession crop takes its place.

Many crops mature before growing season is done, leaving time to plant a second (or even a third) crop. This means we can follow our spring crops with warm season crops and fall crops.

A "succession crop" is just a fancy name for the crop(s) that come after the first crop is done.

Succession planting works in large gardens, small gardens—and even containers!

If you are interested in the idea of a continuous harvest, keep reading: This article explains how you can use the same garden space for more than one crop.

Plan for an Uninterrupted Harvest

As you plan your vegetable garden, there's more than one way to achieve successive harvests. See how you can slot these planting methods into your garden.

Find out more garden planning and layout ideas.

Different Crops - One Follows Another

A common succession planting method is follow one crop with another one. For example, when the summer harvest of green beans is finished, a new crop of kale for winter harvest takes its place.

Different Crops - At the Same Time

Planting carrots and radish together.

Planting two different crops at the same time is not really succession planting, but it's worth mentioning here because it's a useful idea in garden planning, and can be a good way to get multiple harvests from the same space.

Some people use the term companion planting to describe this idea.

Here are examples:

Fast-growing crops with slower crops: My favourite fast-slow combo is to plant beets in the same space as radish. The radishes grow much more quickly than the beets. So you'll have harvested the radishes by the time your beet seedlings need more space. (And don't forget...beet greens are edible too!)

Sun-lovers with Shade-lovers: Another example of putting two crops together is pairing a tall plant with a shade-loving plant. In this case, summertime lettuce (which lasts longer in shade) under tomatoes.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Same Crop - Staggered Plantings to Spread out the Harvest

By staggering plantings of a crop you can get a longer harvest window. This is especially helpful if you grow lettuce or other leafy greens that bolt quickly.

Unless you’re a market gardener, you probably don’t need an entire row of lettuce ready at once. So only plant part of the row. Then, a couple of weeks later, plant more of the same. And repeat.

Same Crop - Different Maturity Dates

Days to maturity (DTM) is a measure of how long it takes a crop to be ready to harvest. Get a few varieties of the same crop, each with a different DTM so that you have an ongoing harvest. Look for DTM on the seed packet or catalogue.

(The number of days it takes for a crop to be ready to harvest varies with growing conditions, so use DTM as a guide, not an exact planning tool.)

Find out more about seed shopping and lingo such as DTM.

Succession Crops

Succession crops are crops that don’t take the whole growing season to mature. They only need part of a season.

Here are common succession crops:

Bush beans are a common succession crop.

Leafy Greens (plan for successive sowings if you want leafy greens during the summer)

Beets (baby beets for pickling are often from a succession crop of beets planted in the summer)

Cabbage

Carrots

Bush beans

Green onions (I keep an extra bag of onion sets in the fridge, ready as a second crop when I need more green onions)

Kohlrabi

Radish and winter radish

Rapini (I like to plant rapini as a mid-summer succession crop when I harvest garlic in July, because it’s fast-growing and does well in the heat of the summer)

Rutabaga

Summer squash (a good second crop where you start off with early spring greens)

Swiss chard (does well in heat without bolting)

Winter squash

Turnip (I like turnip as a late-summer crop…and you can eat the leaves too!)

Find out how to slow down lettuce bolting.

Interested in growing storage crops? Here are 25 storage crops.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Sowing Summer Crops

Hot summer growing conditions are not always suitable for starting seeds directly in the garden.

That’s because:

In hot, dry weather, place a board over fine seeds to keep in soil moisture and improve germination.

Hot weather can affect germination.

In hot, dry summer conditions a crust can form on some types of soil.

Pest pressures are higher.

Here are tips to plant crop successions in hot weather:

Start transplant in pots, in protected conditions.

For plants that are best directly sown into the garden (e.g. carrots), place a board over the soil so that conditions are more moist for germination

Water regularly because dry conditions really mess up germination.

Transplanting Succession Crops

Summer conditions can make transplanting difficult because transplanting into the hot sun is a big stress for the plant.

So wait for a rainy or cloudy day if possible. At the least, don't transplant in the heat of the day.

Make shade for your transplants using mini hoop houses covered with shade cloth or a light floating row cover.

Or even easier: Put an inverted web tray over top of your transplant for a few days. (The webbed plastic trays from garden centres.)

And then water transplants regularly until they are established.

Lettuce transplants for succession cropping.

One Key to Successful Succession Planting

With intensive growing like succession planting, we’re taking more from the soil. That makes it especially important to manage soil fertility. Feed the soil by amending with compost between crops.

Final Succession Cropping Suggestions

Keep extra seed packets on hand for succession planting!

And don’t forget to grow microgreens indoors over the winter.

Find out how to grow our own microgreens indoors.

More Vegetable Gardening Articles

Courses

Prevent Lettuce from Bolting: 5 Ways to Beat the Bitterness

5 Ways to prevent lettuce from bolting as quickly.

By Steven Biggs

Delay Bitterness and Bolting Lettuce

Once day you're looking at a bed of perfect lettuce plants with juicy, tender leaves. Looks like you have enough lettuce for days.

But before you know it the lettuce heads change shape and start to stretch up in the centre. Your lettuce is bolting.

And with the change in shape comes a change in taste. Bitterness comes with bolting.

But there are ways that you can delay lettuce bolting. This article tells you how.

Bolting Lettuce Plants

It's a normal thing for a lettuce plant to bolt. Lettuce plants start out in leaf-making mode. They make leaves, get bigger, store energy.

But as the lettuce plant gets big enough—and as things around it act as triggers—the lettuce plant changes gears and moves into flowering mode. It bolts.

Lettuce plants are annuals, meaning they have a one-year life cycle. In that one year they flower and make seed.

So your bolting lettuce is a normal thing.

Bolting lettuce plants can get quite tall!

What Bolting Lettuce Looks Like

Bolting lettuce looks a bit like plant yoga as the centre of the leaf rosette begins to stretch upwards. Next, the now-lanky lettuce sends up a flower stalk.

Meanwhile, the leaves become bitter and tough.

What Makes Lettuce Bolt?

Bolting is normal. But lettuce plants don't bolt according to the calendar. A lettuce plant bolts because it's triggered by what's going on around the plant.

Here are triggers:

Heat

Dry conditions

Long days

As you see, lettuce bolts as we get normal summer weather. But you can still enjoy lettuce leaves in the summer using the ideas below.

5 Ways to Delay Lettuce Bolting:

Here are ways to keep growing these cool-season plants during the summer for continuous supply of salad greens:

Choose Slow-to-Bolt Lettuce Varieties

Some lettuce varieties don't bolt as quickly in summer weather. As you're shopping for lettuce seeds, look for a "heat-tolerant" or "bolt-resistant" lettuce variety.

Provide Shade for Summer Lettuce

When conditions are cooler and moister in the spring, lettuce does well in full-sun locations.

But as things heat up, give your lettuce some shade. When it's shadier it's also cooler and there's often more soil moisture.

There are a few ways to grow a shaded lettuce crop in the summer:

Growing lettuce in pots placed in a shady location.

Grow lettuce underneath taller crops that shade it. I grow lettuce underneath staked tomato plants.

Put up a mini hoop tunnel with shade cloth over top of the lettuce.

Grow vining crops such as cucumbers over an A-frame—and grow your lettuce in the shaded space underneath

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Mind the Moisture

Well-watered lettuce doesn't bolt as quickly. Water regularly.

If you're growing in rows and can mulch around plants, a generous layer of mulch helps to hold in moisture.

Don't Overcrowd

Prevent lettuce from bolting quickly with heat-resistant varieties, ample moisture, shade, enough space—and a shock treatment!

Stress can cause lettuce to bolt sooner. When lettuce plants are tightly packed into a garden, there's less space for roots, less space for leaves to grow—and less moisture. These stresses can make lettuce plants bolt sooner.

When I sow a bed of lettuce, I seed fairly densely. But as the little lettuce plants grow, I pull out some of the small plants as I harvest. This allows more space between remaining plants.

Shock Treatment

A little shock can temporarily derail the plant's readiness to bolt. Dig up and transplant a few of your perfect heads of lettuce to give yourself a few extra days of lettuce harvest.

A Non-Bolting Lettuce Alternative

Here's another idea for you: Grow a leafy green that won't bolt.

Swiss chard has a two-year life cycle. It's a "biennial."

That means that for the whole first year, the plant makes leaves. It only bolts in its second year.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Let a Few Lettuce Plants Flower

Lettuce producing seeds that float around the garden if left long enough. Grow your own lettuce seed—and attract birds to the garden with lettuce seed.

When the lettuce begins to bolt, I remove most of the plants. But I keep a few.

Here's why to keep a bolting lettuce plant:

Grow your own seeds. You can save the seeds to plant later, or, you can allow the wind to move the floating seeds around your garden.

Attract finches to the garden. I love to watch gold finches swoop in and land on the tall lettuce seed head to dine on the seeds.

FAQ: Bolting Lettuce

Can you eat bolted lettuce?

It's not toxic, but it's hardly palatable. But if you enjoy something that combines bitter and tough, give it a try.

Can you prevent lettuce from going to seed?

Short of killing the plant, you probably can't derail that one-year life cycle that terminates with seed.

But if you follow the steps above, you can delay bolting and seed formation.

What other leafy greens bolt?

Arugula, spinach, cilantro, bok choy, and mustard are common leafy greens that bolt.

More Vegetable Gardening Ideas

Articles

Courses

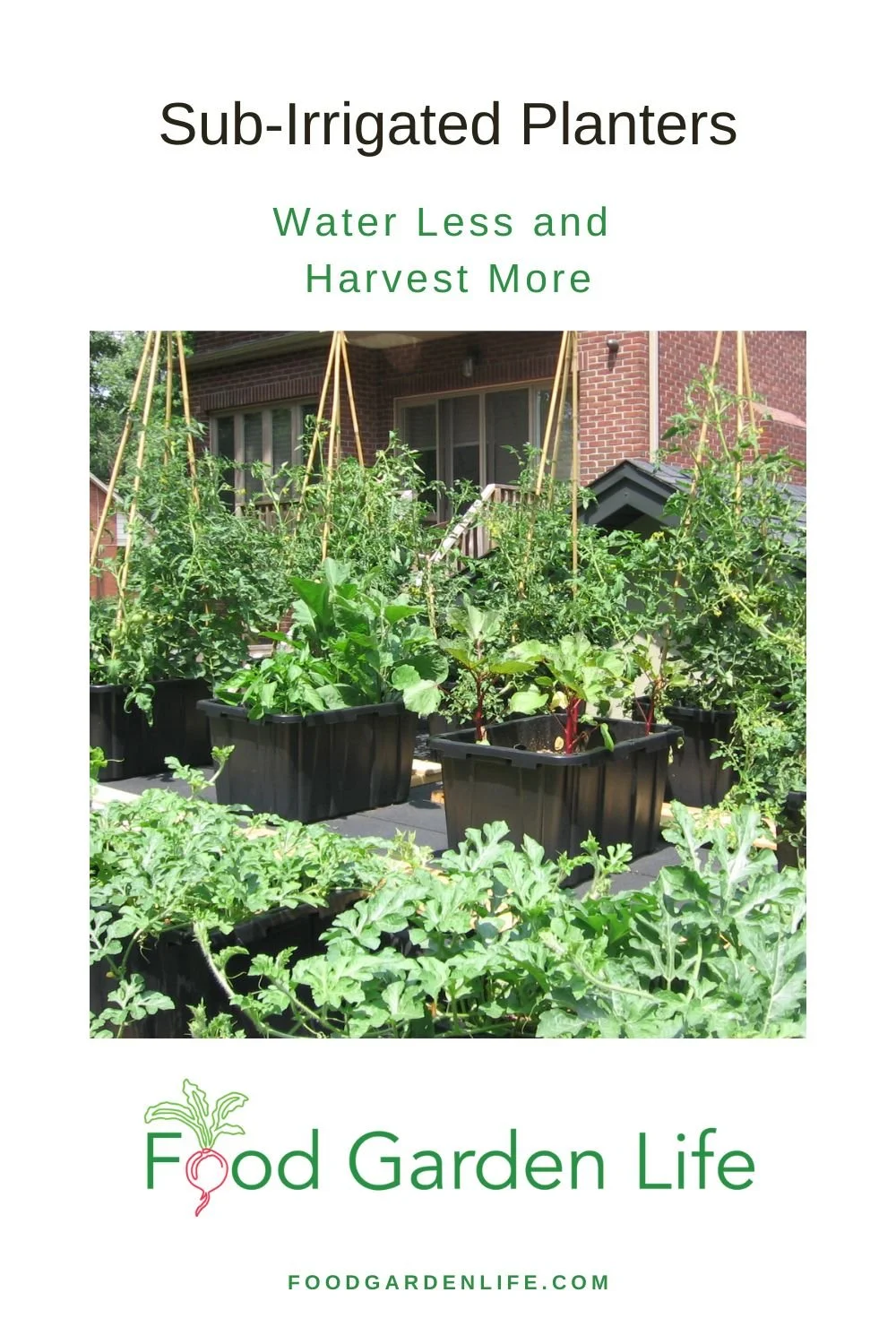

Want to Water Less and Harvest More? Try Sub-Irrigated Planters

Find out how to make your own sub-irrigated planter (a.k.a. self-watering container).

By Steven Biggs

Wilted by Noon

When I first started container gardening on my garage rooftop, I watered every morning. But in the heat of summer, my plants were parched and wilting by noon.

A sub-irrigated planter is an excellent way to solve the problem of parched plants. We want to prevent wilting, because it’s a sign of stress. Drying out is a stress for the crop.

And that stress can delay (or reduce!) your harvest.

Consistent soil moisture is best. Not sopping wet. Not dry.

And that’s where a sub-irrigated planter helps: It keeps the potting mix consistently moist, but not too wet.

This sort of planter is also known as a SIP, a self-watering container, or a self-watering planter.

Keep reading and I’ll explain how a self-watering system works and how you can make your own.

What are Sub-Irrigated Planters?

Sub-irrigation planters are simply planters with a water reservoir at the bottom. The reservoir is right under the soil.

Through capillary action, water wicks up through the potting mix, giving plant roots a consistent supply of moisture. Then, as the plants use water in the soil (creating a moisture gradient) more water wicks upwards from the reservoir.

There are many commercially produced sub-irrigated planters available. Some are fairly basic and resemble a normal container. Others have a gauge that shows the water level in the reservoir.

Self-Watering Planters vs. SIPS vs. Sub-Irrigation Planters

These are all different terms used to describe the same thing: Containers that have a water reservoir below, so that moisture can wick up into the soil.

By the way, they are not truly “self-watering.” The gardener must still fill the reservoir. (If you like do-it-yourself projects, you can automate this with irrigation, see below.)

Benefits of Sub-Irrigated Planters

First, though, let’s look at the benefits of these self-watering containers.

Less waste:

There is less waste of water and fertilizer because it's a closed system, with less runoff

Higher yield because:

A continuously moist growing medium means the plant has no water stress (plant growth can slow, or flowers drop when the plant is under stress…)

When gardening in a container, the growing medium is warmer than soil in the garden, and that means that harvest begins earlier

Fewer weeds because:

The soil surface is not regularly moistened from overhead watering, giving dry surface conditions are not as good for weed seeds to germinate

The other reason that the soil surface is not as wet is that the farther you are from the reservoir, the less moist the soil (remember, it's going against gravity!)

Less disease because:

With no overhead watering, there's less splashing of disease organisms from the potting soil onto the leaves

And with tomatoes, SIPS usually solve blossom end rot (which actually is not a disease, but a physiological disorder that's caused by swings in soil moisture)

And the benefit of a SIP system that goes without saying: You spend less time spend watering!

Where to Grow in a Sub-Irrigated Planter

I made a garden on my garage rooftop using sub-irrigated (self-watering) planters.

As with any sort of container garden, a SIP makes it possible to grow on patios, decks, driveways.

You can also use them to grow over top of areas with tree roots or compacted soil.

If you’ve been eyeing up a space next to that water-hungry cedar hedge, this is your solution!

If you’re concerned about soil contamination, making a container garden is a simple solution.

Find out more about soil contamination.

What’s Inside a SIP

Here's what you'll usually find in a self-watering planter.

A water-tight area (the reservoir) at the base of the container (underneath the potting mix)

Something to hold the potting mix above the reservoir area: it could be a false bottom such as mesh, or hollow containers, or tubing

A way to add water to the reservoir (a fill-tube that extends above the soil surface)

A wick (the wick is usually the potting mix itself, but a fabric wick can be used too)

An overflow hole, so that if there's too much water, it can escape

How a Sub-Irrigation Planter Works

Think of how water moves up a sponge. Or put a piece of paper towel in water and watch the water move upwards.

The same thing happens in a self-watering planter.

The water that's stored in the reservoir moves up through the soil.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Plants That Thrive in Sub-Irrigated Planters

Annual vegetable and herb crops do well in sub-irrigation planters.

Avoid plants that are susceptible to root rot when overwatered. (For example, I grow potted lemon trees, and they hate “wet feet,” soil that says consistently wet. Read more about potted lemon trees.)

Potting Soil for Sub-Irrigated Planters

Choose a potting soil with good wicking properties. Do not use garden top soil or sand.

Sometimes this is easier said than done...because you won't find "wicking" on potting soil labels.

(A bargain isn't always a bargain when it comes to potting soil. If you see discounted bags at big-box retailers, be wary.)

The large compressed bales of potting mix made for commercial growers have a more consistently good quality. If in doubt, start with these.

If you're making your own peat-based potting mix, here’s an important point:

There are different qualities of peat. The darker peat from lower down in a bog is not as good at wicking as the lighter coloured, "blond" peat that comes from the top of a bog. Blond peat isn't always available at garden centres; you might need to go to an outlet that supplies commercial growers to find it.

Make Your Own Sub-Irrigated Planter

It's fairly simple to make your own self-watering planters.

Below is a series of pictures from a batch of planters I made for my garage rooftop garden.

The materials I used were inexpensive, and available at a hardware store:

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric

The tools needed to make these were:

Drill to make overflow hole

Saw or utility knife to cut the weeping tile and dishwasher drain pipe

Scissors to cut the landscape fabric

At the time I made these, I spent about $20 per planter, a fraction of what commercially available self-watering planters cost.

Making a Planter, Step by Step

Supplies to Make a Sub-Irrigated Planter

Plastic storage bin

Weeping tile (4” bendable plastic drain used around the foundation of buildings…the term used for this seems to vary by region)

Dishwasher drain pipes

Landscape fabric (not shown)

Weeping Tile with Fill Tube

Weeping tile coiled around the bottom of the bin.

A hole cut into the weeping tile with a utility knife allows a piece of dishwasher drain hose to be installed as a fill tube.

Landscape Fabric

The reservoir space created with the weeping tile is covered with landscape fabric so that potting soil doesn’t fill up the weeping tile.

Don’t Forget This!

Drill a drainage hole near the top of the weeping tile.

The hole shown here was too small…and was blocked by a piece of perlite, so i had to drill a bigger hole.

Recycled Items to Make a Self-Watering Planter

I've also made self-watering systems using materials from the recycling bin, or things we already had on hand.

Here are examples of items you can use:

For the Water-Tight Reservoir

Retrofitting a large plastic pot to make a sub-irrigated planter. The reservoir is made from old flower pots, which are covered with wire mesh. The wick (not shown) is fabric. The mesh is covered with landscape fabric so that the potting soil does not fill up the reservoir.

A water-tight container such as a pail

Or, a liner to make a water-tight area in a container with holes (for example, pond liner or construction plastic)

To Hold the Soil Above the Reservoir Area

Drainage pipe

Downspout extenders

Downspouts

Weeping tile

Upside-down flower pots

Landscape fabric, or old t-shirts

For a Fill Tube

Water bottles

Dishwasher drain hose

Pop bottles (“soda” bottles if you’re in the US)

PVC pipe

Retrofit Containers into a Sub-Irrigated Planter

A hypertufa planter with sub-irrigation.

You can retrofit any traditional pot into a sub-irrigation system…even if they have holes in them.

Use a liner to make a water-tight reservoir area at the bottom, and then create an overflow hole.

Planter Maintenance

Potting mixes lose structure over time as the organic matter decomposes. Plan to refresh the potting mix periodically. How often you need to do this depends on the mix, and the conditions. Pay especial attention to the soil in the lower area that acts as a wick.

If you're using a fabric wick, check it annually to see its condition. Fabrics made from natural fibres break down fairly quickly.

Sub-Irrigated Planter FAQ

How deep should a sub-irrigated planter be?

Making a sub-irrigated planter from a smaller, shallower planter. This is perfect for shallow-rooted crops such as leafy greens.

A soil depth of about 30cm (12") is usually lots. Remember, gravity is working against the wicking action...and when the soil is very deep the water doesn't wick all the way to the top.

The larger the plant you’re growing, the larger the volume of soil that you'll need. A smaller container with a 15 cm (6") soil depth can be fine for many smaller crops, such as leafy greens. If you're growing something that gets larger, for example bush-type tomatoes, a larger volume of soil is suitable. (That's why I used the storage bins in the example above. Along with determinate tomatoes, we use them for okra, peppers, and eggplant.)

Can I cover the soil on a self-watering planters?

Plastic mulch over the soil holds in moisture and deters squirrels from digging up transplants in the spring.

Yes. A plastic mulch holds in moisture and stops weed seeds from germinating. There are biodegradable plastic mulches that last for a single growing season.

Lay the mulch over the potting mix, and then tuck it in tight at the sides. Once it's snug, you can cut and X in it with a sharp knife, and then plant into the X.

A springtime challenge for us is squirrels digging up newly transplanted seedlings from our planters. A simple solution is the plastic mulch, which seems to deter digging. (Soil is out of sight, and it’s out of their wee little squirrel minds.)

Or, if you don't like the look of the plastic, burlap works well too. (It's a natural fibre, so doesn't hold in as much moisture, but it deters digging and reduces growth of weed seeds.)

What about watering plants in a SIP from above?

This is fine. It will keep the soil surface moister, so there's more chance of weed seeds germinating. But there's nothing wrong with this...other than it can be much slower than filling using a fill tube.

Can I reuse the soil in my self-watering planter?

Over time, as the organic materials in soil break down, potting soil loses its structure. When is has less structure (fewer bigger particles and fewer air pores) it doesn’t wick as well.

So for best wicking, fresh potting mix work best.

But...replacing potting mix every year is both wasteful and expensive. I usually mix in some new soil mix every year, about 20 per cent.

What is an Earthbox?

It is a well-known brand of sub-irrigated planters.

Is a “global bucket” a sub-irrigated planter?

Yes. I suggest you search online to find out more about this easy-to-make pail-in-pail SIP planter that has a reservoir.

What is a wicking bed?

With a wicking bed, we're taking the same ideas we use in a sub-irrigated planter—just on a larger scale. Now we’re talking about a raised bed. A wicking bed has a water reservoir, fill tube, and overflow just like a SIP does.

If you’re researching wicking beds, you’ll see that the names SIP and wicking bed are often used interchangeably. For me, if it’s a moveable planter, it’s a SIP. If it’s a permanent bed, it’s a wicking bed. But don’t sweat the lingo—as long as you understand how it works inside.

Find out more about wicking beds.

Are there any things to watch for with SIPS?

Yes, salt build-up. Normally, excess salts that can accumulate near the soil surface wash away with watering, and then drain from the bottom of a container. But with a SIP, we’re not washing down salts with water, and any runoff is captured.

That means it's a good practice to flush out your SIPs in the spring. Water heavily from the top, enough to cause lots of water to drain through the overflow holes and carry away excess salts.

How can I automate watering in my self-watering planter?

An irrigation spaghetti tube goes into the fill tube on the SIP.

You can set it up with automatic irrigation that refills the reservoirs.

You want what’s called “spaghetti tubes,” small tubes that run from an irrigation line. One tube goes to each planter. (This sort of system is often used to irrigate container gardens, with “drip emitters” at the end of each spaghetti tube to regulate how much water comes out and onto the soil surface in the container.)

But when you’re setting up spaghetti tubes and drip emitters for a SIP garden, just put the tube and drip emitter right into your fill tube, so that when you turn on the irrigation, you’re replenishing the water in the reservoir—not wetting the soil surface. (That way, less water is lost to evaporation, and you’re not creating conditions suited to weed-seed germination.)

Experience will teach you how long to leave on the water supply to fill up the reservoir.

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Course

Get great ideas for your edible garden in Edible Garden Makeover. Planning. Design. Crops. How-to.

How to Make a Wicking Bed

Harvest more and water less when you grow in a wicking bed. Find out how to make a wicking bed.

By Steven Biggs

Make Your Own Wicking Bed

Harvest more. Water less.

Wicking beds are a great way to maximize the use of space in a small garden. They also save time for busy gardeners.

What’s a Wicking Bed?

A wicking bed is simply raised bed with a reservoir—a water storage area—at the bottom.

They work the same way that sub-irrigation planters (a.k.a. SIPS or “self-watering” pots) work.

Find out more about sub-irrigated planters.

Water wicks upwards from a reservoir below into the soil above through capillary action.

Keep reading to find out how to make a wicking bed.

Less Plant Stress

When plants get thirsty—when there is “water stress”—it can have a big effect on yield.

Because wicking beds prevent water stress, the increase in yield can be considerable. Of course, no one minds the time saved by having to water less frequently.

Even in the heat of summer, when the tomato plants are quite big, we water our wicking beds about once a week.

We turbo-charged our backyard tomato production using wicking beds.

Another Reason to Use a Wicking Bed

Our neighbour’s large black walnut tree is beautiful. But walnut trees give off a compound called “juglone.” And juglone affects the growth of many plants…including tomatoes.

We tried growing tomatoes in the backyard many times…and they always died.

BUT MY DAUGHTER Emma had a vision of a tomato plantation in our backyard, near that walnut tree.

I wondered if we could solve the problem by growing in wicking beds, because the tomato roots would never get into the juglone-contaminated soil below.

It worked—and we now grow tomatoes right under the walnut tree.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Make Your Own Wicking Bed

Be creative with the materials you choose. We decided to use cedar fence posts to make our wicking beds.

Below are photos of wicking beds that I made with my kids using cedar fence posts.

I chose cedar fence posts because they are long-lasting and not much more expensive than dimensional lumber.

Beds made with dimensional lumber often sag outwards over time...and I’m not interested in rebuilding my wicking beds any time soon.

I chose pond liner to create the reservoir because I already had pond liner here.

Be Creative

Be creative! You might want to make a wicking bed from salvaged material—or maybe you want a bed that ties in with the aesthetic in your landscape.

On the practical side, I’ve see wicking beds made from large plastic bins and from recycled lumber.

On the ornamental side, I think red brick would look smashing! One day…

Materials List for My Wicking Bed

Cedar fence posts.

Pond liner. The pond liner holds water in the bottom of the bed. Once the sides of the liner are bent upwards and fixed into place, it creates a shallow water storage area at the bottom of the bed--about as high as the weeping tile.

Weeping tile.

3/4” gravel. Use “clear” gravel, which means that it does not have smaller pieces of gravel that will fill up the spaces in between. That way the space is available to hold water.

Dishwasher drain tube. To create a fill tube.

Landscape fabric. Its purpose is to keep the soil from filling up the piping and the spaces between gravel.

Steps for Making a Wicking Bed

Cut posts to length and notch the ends.

Place notched posts directly on the ground. Level the ground first.

Nail spikes into the corners of the posts to keep them in place.

Install liner at the bottom by placing it on the ground, and up about 8-10 inches at the side. Secure temporarily with staples, to keep it in place until the gravel pins it into place.

Place coils of weeping tile in the bottom. The tile permits water to quickly move through the reservoir, and it also holds up the soil above.

Add gravel. It supports the weight of the soil above, while the spaces between the pieces of gravel fill with water. Water moves upwards through the gravel by capillary action.

Note the fill tube at the far end, a piece of drain hose installed into the weeping tile. This permits filling of the reservoir with a hose after soil has been added.

Cover with landscape fabric to keep soil out of the reservoir area. Note the depressing in the top-right corner: While in theory water wicks up the gravel, I also created this soil-filled wick that dips into the reservoir.

Approximately one foot of soil works well. If there is too much soil, the water will not wick all the way to the top.

Watering my Wicking Beds

I know that there is enough water in the bed as I'm filling it because once the storage area is full of water, I see water coming out of the side of the bed. It's low-tech—but it works.

One More Reason for Wicking Beds

Soil contamination is another reason to consider growing in a wicking bed. Soil contamination can be a concern in areas where there is a history of industry, and also on former orchard lands where sprays with heavy metals might have been used.

Find out more about soil contamination and what to do about it.

Another Way to Add Growing Space in a Small Garden

Straw-bale gardening is a great way to grow on paved areas and areas with poor soil.

Find out more about straw-bale gardening.

More on Growing Vegetables

Articles and Interviews

Courses: Edible Gardening

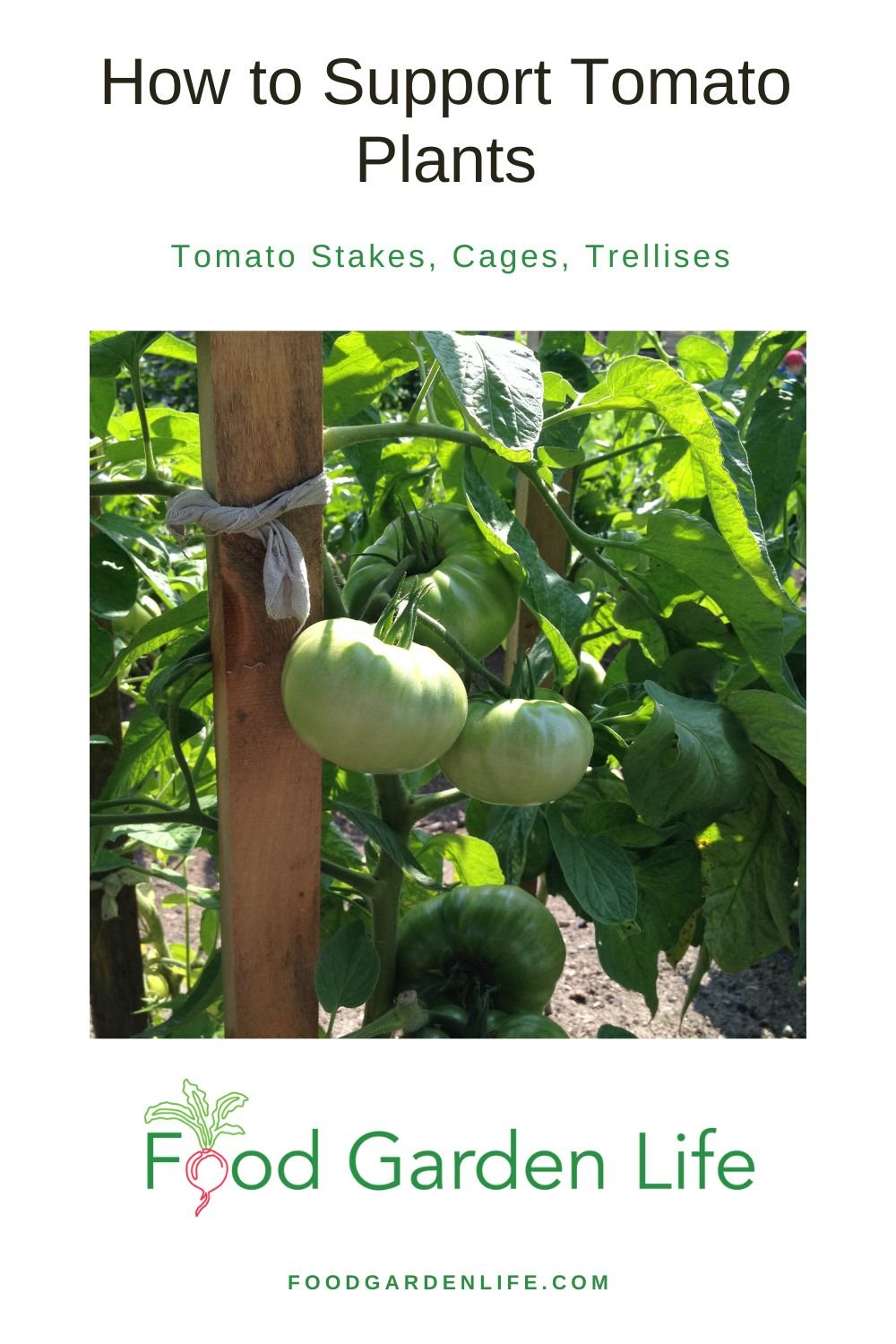

Tomato Staking Guide: How to Support Tomato Plants

Support those tomato plants! This guide tells you how to stake, trellis, train, and cage tomatoes so you can fit in more plants and get a great harvest.

By Steven Biggs

Tomato Stakes, Cages, Trellises

Support tomato plants. Pick a method that suits your garden and your style of gardening.

Joe stakes his tomato plants.

I don’t.

My neighbour Joe’s backyard is all garden. Full-on tomato production. He fills it with row after row of tomato plants, neatly staked, pruned, and trained.

My garden is maxed out on tomatoes too. But my tomato patch looks entirely different from Joe’s.

I grow some tomato plants in cages. The tomato plants on my driveway (where I can’t hammer in a stake) are supported by a trio of stakes in a teepee formation.

In another area, I grow tomatoes up twine.

Joe and I both grow our tomato plants in ways that suit our garden layout and approach to gardening.

This guide to staking and supporting tomato plants will help you pick a method that fits your garden.

To Stake or not to Stake

When tomato plants are staked or supported, the fruit isn’t touching the soil.

The easiest way to grow tomato plants is to simply let them sprawl on the ground.

This is how tomatoes are often grown on a field scale. Take a road trip to a tomato-growing region such as Leamington, Ontario, and you’ll see fields with tomato plants sprawling on the ground.

There are reasons for home gardeners to support tomato plants:

When tomato plants are staked or supported, the fruit isn’t touching the soil, meaning clean tomatoes, and less chance of rot and insect damage

Upright plants take up less space…so if you stake tomatoes, you can fit more plants into your garden

An upright tomato plant has more air circulation around the leaves—and that reduced the chance of disease

In my garden we have a high-density approach to growing tomatoes because my daughter grows over 100 varieties in our urban yard. We grow them much more densely than many gardeners, but it works well because we support and prune the plants.

Tomato Support Depends on Plant Type

The type of tomato plant you grow affects the need for staking and pruning.

“Dwarf” tomato plants are quite compact and usually don’t need any pruning or support. Great for container gardeners!

“Bush” tomato plants (also called “determinate” tomato plants) get to a certain height and then don’t get any taller. The harvest window is shorter. Great if you want a concentrated harvest for sauce-making or processing. Stake or cage determinate tomato plants to increase planting density and to keep tomatoes off the ground.

“Indeterminate” tomato plants keep getting taller and taller all summer long. Great if you want an ongoing harvest. This is the sort of tomato plant often grown in commercial tomato greenhouses. Prune and support indeterminate tomato plants to optimize production—and know that they can get very tall by the end of the summer.

Tomato Staking and Support Ideas

There are lots of ways you can stake and support tomato plants. Pick one that suits your garden and the amount of time you want to spend tending your tomato crop.

Here are ideas for supporting your tomato plants:

Staked tomato plants with wooden tomato stakes.

Tomato Stakes

Tie your tomato plant to a stake. A lot of gardeners keep one main stem, pinching off side shoots (called suckers). See ideas for tomato stakes below.

Tomato Cages

Grow the tomato inside a supportive cage-like frame. Plants in cages can be wider—so having more than one main stem is common. See below for a tip on making your own tomato cages.

Grow Tomato Plants up Twine

Visit a commercial tomato greenhouse and you’re likely to see tomato plants growing up a piece of twine suspended from above.

We use a variation of this twine method in our garden, where we make tall A-frames with bamboo, and run a horizontal pole between them—six feet up in the air. Then we dangle pieces of twine from the horizontal pole, and train our tomato plants up the twine. This way we can space our tomatoes very closely together so that we can fit more tomato varieties into the garden.

We make tall A-frames with bamboo, and run a horizontal pole between them.

Then we dangle pieces of twine from the horizontal pole, and train our tomato plants up the twine.

Florida Weave for Tomatoes

The “Florida Weave,” where twine supported by two end stakes is woven around the tomato plants for support.

In this method of supporting tomato plants, we weave the tomato stems between horizontal rows of twine. Start by putting stakes at both ends of your tomato row. As plants get taller, keep adding rows of twine, and weave the stems between them.

Grow a Tomato Arch

If you have an archway in your garden, use it for tomato plants.

Indeterminate tomato varieties get taller, and taller, and taller. As they reach the top of the arch, you can train them down the other side.

Tomato-Staking Tip

Don’t get hung up on supporting tomatoes the “right way.”

There are many ways to do it—and you just need to pick one that suits the way you want to garden and the type of tomato plants you’re growing.

Make Your Own Tomato Cages

Make a tomato arch with cattle panel wire.

A lot of the so-called tomato cages sold at garden centres are just too small to be useful. And if you find larger cages, they can cost you an arm and a leg.

We make our own tomato cages from the sheets of wire mesh used to reinforce concrete.

Cut the 4’ x 8’ sheet into two 4’ x 4’ sections (bolt cutters work well)

Then, bend the mesh into a cage

The bending takes effort as this is a strong material (I find that it works best if I place a board over the line I want to bend along, and then stand on the board as I bend the wire upwards)

These homemade tomato cages are long-lasting. Our oldest ones are over 15 years old and going strong.

If you’re creative, you might come up with other materials to make your own tomato cages. I’ve seen old bundle buggies used!

Be creative! A bundle buggy as a tomato cage.

My daughter Emma and I made our own tomato cages by cutting and bending wire mesh.

Tomato Stake Ideas

Bamboo stakes are an option for staking—but be sure to get large enough stakes as smaller ones might be too flimsy.