How to a Grow a Mulberry Tree

How to grow mulberry in cold climates.

By Steven Biggs

Fowling in Love with Mulberry

My neighbour Hubert handed me a pheasant and a duck from his freezer. I was working for the summer in a rural part of the UK, and regularly saw pheasant when I went out for a jog. Now I’d get to taste one!

As a 20-something-year-old, I’d never cooked either before…and had never even tasted pheasant.

But I remembered reading that the meat is rich and dark, well-suited to a tangy accompaniment.

And I remembered a mulberry tree in a nearby hedgerow.

I’d been grazing fruit from the mulberry tree every time I walked past it. But I had yet to cook the mulberry fruit.

This was my chance! Not really sure what I was doing, I made up a mulberry-Cointreau sauce for basting the roast. The company I had for supper thought it was pretty good.

Roasted fowl with mulberry-Cointreau sauce cemented my appreciation for the taste of mulberry.

Mulberry for Home Gardens

There are many types of mulberry suited for gardens in cold climate. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

Mulberries gets a bad rap. Mention mulberries and many people picture polka-dot-stained sidewalks and bird-bespattered cars. Or experienced gardeners worry that it’s a weedy plant.

Why is it that gardeners always want what’s difficult to grow? Why not appreciate what grows on its own?

This fruit does not play hard-to-get.

Mulberry is a great fit for home gardens because it’s:

Fast-growing

Hardy

Problem-free

Tolerant of many conditions

Very fruitful

And it’s a fruit that you likely won’t find for sale at grocery stores. Too fragile to ship when ripe.

Too bad mulberries get a bad rap for being vigorous growers.…and for the purple stains from falling fruit. They’re a great fruit for home gardens in cold climates.

What does a Mulberry Tree Look Like?

What does it look like? The question should really be, “What does a mulberry tree look like when pruned to feed people, not birds. (More on that below.)

Don’t grow this as a specimen shade tree. There are nicer shade trees out there.

Grow mulberry as a fruit-producing crop – which means you’ll keep it much smaller than if left unchecked.

Types of Mulberry for Cold Climates

Mulberry names don’t describe the fruit colour. That means a white mulberry tree could be black-fruited, red-fruited, or white-fruited.

If you’re shopping for a mulberry tree, here at the three types you’re likely to find in North America:

• White mulberry (Morus alba)

• Red mulberry (Morus rubra)

• Black mulberry (Morus nigra)

Mulberry names don’t describe the fruit colour. While this ‘Carman’ white mulberry fruit is white, other white mulberry varieties can be purple or black. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

For cold-climate fruit growers, it’s the white mulberry and its hybrids with the red mulberry that are hardiest, some into USDA zone 4.

I’ve read articles in British gardening magazines that disparage the less flavourful white mulberry…but it’s what we have.

White mulberry can grow up to about 15 metres (50’) tall. Because it grows easily from seed—and because birds quickly spread the seeds—feral white mulberry trees are common. (It’s considered a weed tree in some jurisdictions.)

Red mulberry is a native of North America. Pure red mulberry trees are rare because feral white mulberry and red mulberry hybridize readily. Here in Ontario, where red mulberry is native in the south of the province, its threatened by the white mulberry due to their promiscuous hybridizing.

The more diminutive black mulberry, noted for the quality of its fruit, is less hardy, and not suited to northern gardens. It’s suited to conditions in USDA zones 6 and higher.

Other thoughts on selecting a mulberry tree:

There are weeping varieties that get to about 3 metres (10’) tall and can be perfect for small-space gardens (just beware, as there are fruitless varieties of weeping mulberry on the market)

There are dwarf varieties that get to about 6 metres (20’) tall

White-fruited varieties might be the ticket is you’re averse to mulberry stains

‘Illinois Everbearing’ is noted for having a long season of fruiting

Plant a Mulberry Tree

Mulberry trees fend for themselves quite well once established, but here are things you can do to give them a good start.

If you’re planting a container-grown mulberry tree, the first thing to do is look at the roots. Because mulberry is a vigorous grower, it’s common to find roots tightly wound around and knitted together.

Use your fingers to tease apart the roots. We want the roots to grow outwards into the surrounding soil once planted, not continue to grow around in circles.

Water well when first planted and until established.

Pruning Mulberry Trees

Many sources suggest that regular pruning is not necessary with mulberry.

That’s fine if you want to feed the birds.

But if you’re growing the mulberries for yourself, I suggest a different approach: Be aggressive – and do it every year.

Your goal is to create a permanent scaffold of branches that you cut back to every year (see below).

Formative Pruning

Grow mulberry trees in an umbrella shape, so you can reach all of the fruit. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

The best way to get a tree with a well-arranged scaffold is to make it yourself. Get a whip, which is a young, unbranched tree. (You probably won’t find this sort of tree at a garden centre; look for a specialist fruit-tree nursery.)

Then prune that whip so that it grows into a spreading tree. Think short and wide.

Start this pruning process by removing the “leader,” which is the growing tip of the tree. Linda Grimo, at Grimo Nut Nursery, a specialist nursery, suggests, “Stand as tall as you can with your pruners in your hand and clip off the top of the tree.” She explains that this stops it from growing upwards, and encourages the growth of side branches at a height you can reach without a ladder.

Umbrella-shaped mulberry tree in summer. Prune hard to keep berries at picking height. Photo by Grimo Nut Nursery.

Grimo says she likes to grow mulberry trees in an umbrella-shaped scaffold, with side branches (laterals) spaced out around the tree. For ease of getting under the tree to pick, don’t grow the side branches too low on the tree; her preferred height is just over a metre (4’) above the ground.

Annual Pruning

Mulberry trees growing in good soil put on a tremendous amount of growth every year. After formative pruning is complete, prune back almost all of the new growth every year, leaving just 1-2 buds from which the tree can send up replacement shoots.

This harsh pruning doesn’t affect cropping because fruit forms on new growth. “Don’t be afraid, you can’t kill a mulberry tree,” is what Grimo tells concerned first-time mulberry growers.

Prune in late winter, when dormant.

Mulberry Tree Feed and Water

Mulberry trees have extensive root systems, which means that they can do quite well without coddling.

Mulch with compost around the base of the tree to feed the soil and suppress weed growth.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Mulberry Tree Pollination

Mulberry trees are self-fertile, which means you only need one tree to get fruit.

The small, unremarkable flowers are wind pollinated. (There are even some varieties that set fruit without pollination.)

Mulberry Tree Propagation

Dwarf or weeping mulberry varieties are well-suited to use in small-space foodscapes, even in more traditional gardens.

Mulberry plants grown from seed will be different from the parent plant. Just like apples. There is a juvenile period before a seed-grown mulberry tree will flower and produce fruit, often 5-10 years.

It’s easy to grow from seed. In fact, this is a tree that might just seed itself in your garden.

I don’t recommend growing mulberry from seed, because you don’t know what the fruit quality will be like—and you’ll have to patiently wait through that juvenile stage.

Another unknown if growing from seed: Some mulberry trees are dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are on separate plants…and that could leave you with a tree that doesn’t bear any fruit.

If you want good fruit quickly, start with a known variety. Clonally produced trees—grafts and cuttings—can fruit right away because the clone is from a mature tree, and no longer in the juvenile stage.

Some nurseries propagate mulberry by cutting, some by grafting. For grafting, Grimo says cleft grafts work well. Propagation from cuttings can be more challenging for home gardeners without a misting system, bottom heat, and rooting hormone.

Mulberry Trees in Garden Design

Mulberry trees are quite versatile in garden design. Here are ideas for using mulberry trees in the landscape:

Dwarf or weeping varieties are well-suited to use in small-space foodscapes

Large, minimally pruned mulberry trees can be used for a canopy layer in a food forest

Smaller mulberry varieties can fit a forest-edge niche in a food forest because the tree tolerates partial shade

From a permaculture perspective, mulberry is an interesting option because along with fruit, it can provide poles and animal fodder (see below)

Mulberry for More than the Fruit

Because it grows very quickly, mulberry is well suited to pollarding and coppicing techniques. Here are branches from my neighbour’s mulberry pollard that I use as poles in the garden.

Mulberry is an excellent tree choice if you’re gardening with a permaculture mindset.

My neighbour Troy used to give his mulberry tree a harsh haircut every year. The long, straight branches made excellent poles that he gave me for staking plants and making trellises.

He grew his tree as a “pollard,” meaning he lopped off all of the growth a few feet above the ground. (Pollarding is often done with catalpa trees, for ornamental purposes.)

The other twist on this idea of using your mulberry tree to produce poles, is to grow it as a “coppice.” Coppicing is when you cut off a tree close to the ground to get it to send out lots of stems. Coppicing has traditionally been used to produce wood for baskets, fences, and fuel.

Mulberry Tree Location

Mulberry trees prefer full sun and rich soil. But they tolerate partial shade and a variety of soils.

And much worse.

To say they’re forgiving of poor conditions is an understatement.

I’ve seen lovely mulberry trees growing between cracks in the pavement. They do amazingly well in inhospitable locations. As I write this I’m looking out the window at the self-seeded mulberry tree in my front garden that I’m training into an espalier. It’s growing right underneath a row of spruce trees, hardly an ideal location. But it persists!

So save the prime real estate in your garden for plants that really need it. Your mulberry isn’t fussy. And, remember, pick a spot where purple spotting is not a nuisance.

The one thing to avoid is standing water. Pick a well-drained location, though occasional wetness is fine.

Challenges

Your mulberry tree will be a bird beacon.

Got a white car? Hanging out clothes to dry?

Then you might want to net the tree to keep away the birds. Netting is easier to do when you’ve grown a compact mulberry tree.

Harvest and Store Mulberries

If you’ve started with a tree grown from a graft or cutting, you might start getting fruit in as little as 2-3 years.

Not all the fruit on a tree ripens at the same time. As they ripen, fruit fall to the ground.

White mulberries can be very sweet, while black mulberries are more balanced, with some tartness. I prefer white mulberries a little bit under ripe—while they’re less sweet. (Remember, a white mulberry tree can have black fruit!)

A couple notes on picking mulberries:

The fruit are fragile, and the juice easily comes out of the fruit when picked…so expect red hands if it’s a dark-coloured variety

Ripe fruit will drop from tree as you pick

A common recommendation when harvesting from large mulberry trees with many unreachable fruit above is to place a sheet on the ground and shake the branches.

The fruit has a short life once picked. There’s a little stem on it – and you can eat it stem and all.

Here are 6 simple ideas to grow lots of fruit in a home garden.

Mulberries in the Kitchen

You can use mulberries raw, use them in preserves, or cook them. Here are ideas:

Mulberry pie

Mulberry wine

Mulberry cobbler

Mulberry liqueur

Dried mulberries (great in a trail mix!)

Mulberry juice

Mulberry FAQ

How fast do mulberry trees grow?

Mulberry trees grow very quickly.

Where do mulberry trees grow?

White mulberry and its hybrids are suited to cold-climate gardens into USDA zone 4. Black mulberry is less cold-tolerant.

Can you grow a mulberry tree from a cutting?

Yes. You can grow mulberry trees from cuttings.

Do mulberries grow on trees or bushes?

Mulberries naturally have a tree form, but you can prune to encourage branching and a bush-like shape.

Can you grow a mulberry tree in a pot?

Cold-climate gardeners who are determined to try black mulberry can grow it in a pot that is stored in a protected area over the winter.

How do you keep a mulberry tree small?

Prune it very aggressively every year.

Do mulberry trees grow near black walnut trees?

Mulberry trees are not affected by the compound “juglone” that is given off by black walnut trees. So if a black walnut tree has limited your growing options, consider mulberry.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Fruit

Get our free guide with 6 ways to grow more fruit in your garden.

Articles and Interviews about Growing Fruit

Here are more resources to help you grow fruit.

Courses on Fruit for Edible Landscapes and Home Gardens

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

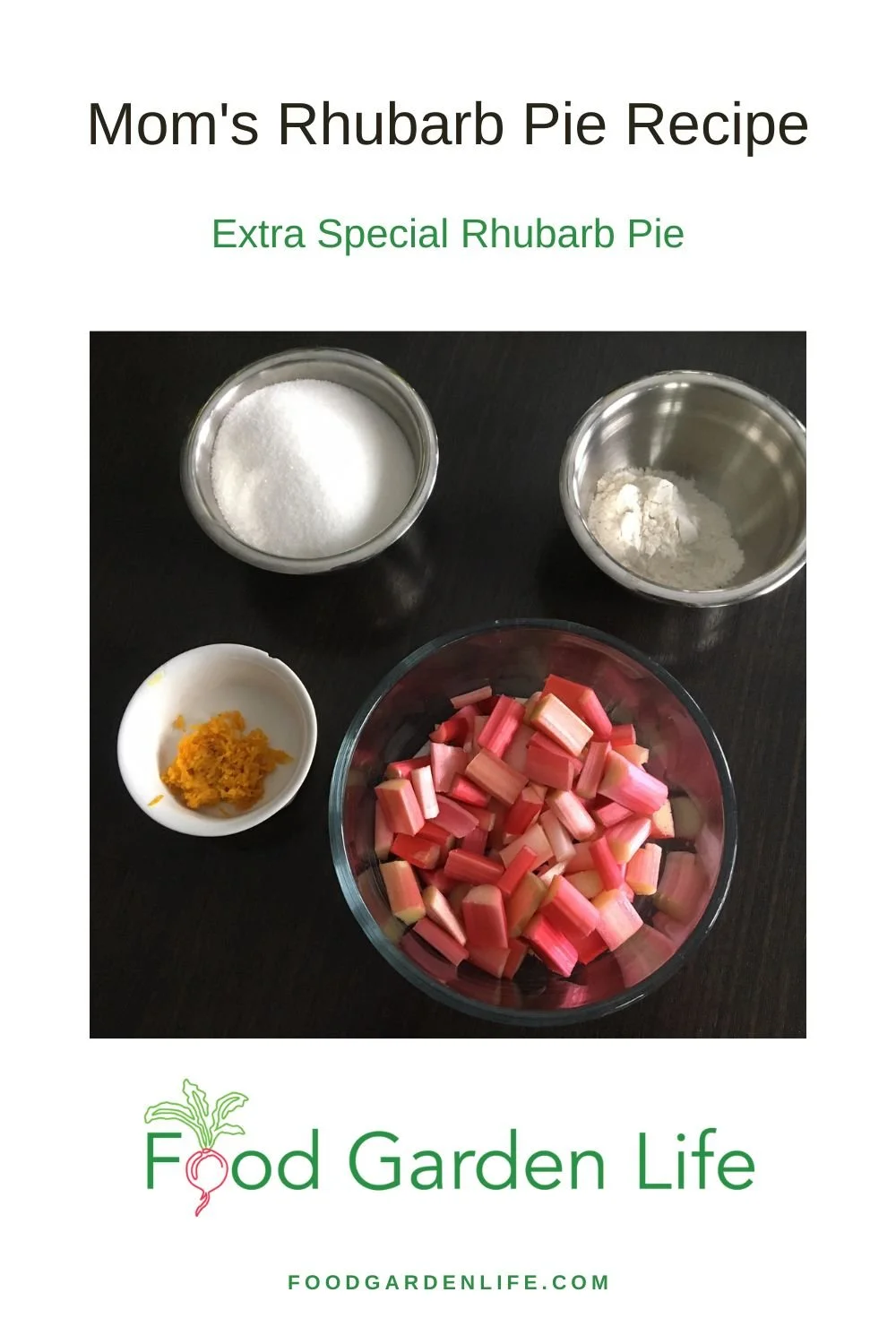

Mom's Rhubarb Pie Recipe

Mom’s rhubarb pie recipe. This is a very good rhubarb pie!

By Steven Biggs

Stalking Out the Best Rhubarb for Pie

In spring, Mom put an upside-down bushel basket over a corner of her rhubarb patch. The dark, warmer conditions within coaxed longer, rosy-red stalks from the rhubarb roots below.

Those rosy-red stalks made great rhubarb pie.

Ingredient for an Extra Special Rhubarb Pie

Mom’s spring-forced rhubarb made great pie because when you force rhubarb—when you grow it in warmer, dark conditions—you get stalks with a bright red colour. It’s quite different from the stringier, greenish-red stalks you get from rhubarb exposed to sunlight.

Along with the colour, the other thing about forced rhubarb is that it’s more tender. Cooked into a pie, it’s melt-in-your-mouth tender.

So I recommend forced rhubarb if you want an extra special rhubarb pie.

If not, though, regular rhubarb still makes great rhubarb pie. I share Mom’s recipe below.

Where to get Forced Rhubarb

Rhubarb I forced in my basement.

Force it yourself: You can force it in the garden, like Mom did—or you can even force it indoors over the winter.

Find out how to force your own rhubarb indoors over the winter.

Depending where you are, you might also be able to buy forced rhubarb in the winter and early spring.

Another Special Ingredient for Rhubarb Pie

Mom always added orange zest to her rhubarb pie. It’s a pairing that I love. I think they’re made to go together. The orange zest doesn’t blunt the tanginess of the rhubarb or disguise the flavour.

Because I grow potted citrus here in Toronto, I experiment with other types of citrus zest. Yuzu and Meyer lemon zest both work very nicely with rhubarb.

Hear about cold-hardy citrus such as yuzu.

Find out how to grow a potted Meyer lemon tree.

The Rhubarb Pie Crust

Mom used vegetable shortening. My wife, Shelley, swears by lard, like her grandmother taught her to use.

I’m not too sophisticated when it comes to pastry…but I appreciate a good one. If I’m in a rush, I just buy a pre-made pastry shell.

These days I have a rolling pin, but in my first kitchen, I rolled my pastry with a quart beer bottle. (Labatt 50 in case you’re wondering!)

Pastry-Related Tip

Something that I think works very nicely with rhubarb pie is sugar granules on the crust. It looks nice—and fits well with the sweet-and-sour in a rhubarb pie.

Here’s what to do:

Before you pop your pie into the oven, brush the top with milk, and then lightly sprinkle sugar over the top.

Serving Rhubarb Pie

Keep it simple.

Vanilla ice cream or whipped cream are all that I’d pair with rhubarb pie.

I was once served rhubarb pie with chocolate ice cream. Yuck! It hid the rhubarb flavour.

Soggy Bottom Crust and Rhubarb Pie

When I was learning to make pie, Mom explained why she liked to start off her rhubarb pie at a higher temperature. The higher temperature was to make sure the bottom crust isn’t soggy.

Because there’s a lot of moisture in rhubarb, it’s common to get a soggy lower crust. A blast of higher heat when you first start baking helps prevent that.

Rhubarb Pie Recipe

Ingredients

Only 4 ingredients in this easy-to-make rhubarb pie recipe.

4 cups chopped rhubarb

1 cup sugar (I actually prefer pie with ¾ cups of sugar, but Mom used a cup)

¼ cup flour

Zest of half an orange

Directions

Chop rhubarb into 2 cm (3/4”) pieces

Mix together ingredients

Place in a pie shell

Put on the upper crust (crimp well with a fork because this is a juicy pie, and you don’t want that precious juice coming out the side!)

Use a fork to poke some vent holes in the upper crush

Bake at 450°F for 10 minutes

Turn down the temperate to 350°F and bake 30 more minutes

More on Rhubarb

Hear farmer Brian French explain how he forces rhubarb.

Find out how to force your own rhubarb.

Did You Know?

Rhubarb looks great in an edible garden. My neighbour Chris planted it next to his pond because of the large tropical-looking leaves and the charming flowers.

If the idea of a garden that has edible plants woven into it, you might be interested in my Edible Garden Makeover masterclass.

More Food Gardening Resources

Course

Create your own edible oasis…including a patch of rhubarb. Edible Garden Makeover guides you through creating an edible garden you love.

Guide to Growing Nanking Cherry: An Easy-to-Grow Bush Cherry

Guide to growing Nanking Cherry, an easy-to-grow cherry bush.

By Steven Biggs

Grow Nanking Cherry

The Nanking cherry bush has a spectacular bloom early in the spring.

“Dad, someone’s taking a picture of your garden,” shouts one of the kids. It’s early May, so I know which plant will be in the photo.

The Nanking cherry, a.k.a. Prunus tomentosa. Even though our front garden is a party of spring flowering bulbs, when the Nanking cherry is blooming, it steals the show.

The Nanking cherry bush is like a stop sign. Pedestrians going past our house change gears from a brisk walk to a full stop and then take photos.

Spring isn’t the only time it looks great: it looks great again as the fruit colours up. And unlike cherry trees, where you have to look upwards, this cherry bush is at eye level.

Perfect Fruit for a Home Garden

Nanking cherry is ideal for a home food garden because it’s compact, ornamental, and easy to care for. By comparison, many fruit trees require a fair bit of pruning and pest and disease management. And they take more space.

The small, bright-red cherries are juicy. I’d place the taste somewhere between sweet and sour cherries.

Where to get Nanking Cherry

Nanking cherry flower buds

When I teach about edible landscapes, most students haven’t heard of Nanking cherry because it’s not too common in the horticultural trade. It’s a pity because this is such a fantastic home garden fruit bush.

Look for a nursery specializing in fruit and cold-hardy plants. Or, better yet, find somebody who is already growing it, because many of the seeds that drop around the bush will grow.

(I once mentioned this to my class and was asked by students if that meant I had extras to share. I did. And I took in a tray of small cherry bushes the following class.)

By Seed

While many fruit trees and bushes are propagated commercially by cuttings or grafting, Nanking cherry is commonly seed grown. You can grow them from seed at home:

Look for small Nanking cherry plants growing from seed near a mature, fruit-bearing bush.

When saving seeds to grow, don’t let them dry out too much

In the fall, place seeds in damp potting soil

Store potted seeds in a cold location until spring (a fridge or animal-free shed or garage is fine)

In spring, watch them grow!

When you grow from seed, the seedlings will all be genetically distinct, so expect some variability between plants. Seed-grown plants often flower in less than five years.

Cuttings

If you have a Nanking cherry plant that you really like, you can also propagate it from cuttings. Root softwood cuttings in early summer, as fruit ripens, or root cuttings from dormant hardwood in the spring. High humidity and rooting hormone increase the percentage of cuttings that root.

Create Your Own Unique Edible Landscape

That fits for your yard, and your style!

Layering

Another way to propagate Nanking cherry is by layering. This is the practice where a low-lying branch is covered with soil until it grows roots and can be detached from the main plant. I find it’s often enough to simply to pin a low-lying branch to the soil by covering it with a brick.

Nanking Cherry Varieties

Red-fruited, white-flowered varieties of Nanking cherry are the most common in the horticultural trade.

There are not a lot of improved varieties available commercially. At the time of writing this, I’ve just ordered one called ‘Pink Candles.’

Along with the common seed-grown, white-flowered, red-fruited Nanking cherry varieties, look for:

White-fruited varieties

Pink-flowered varieties (like ‘Pink Candles, above)

Cold-Climate Cherry

If you’re gardening in a cold zone, Nanking cherry withstands cold winters and hot summers. My grandfather grew Nanking cherry in Calgary, a mercurial climate if ever there was one. His cherry bushes soldiered on through snow in summer and balmy winter chinook winds.

(Incidentally, he also made wine from Nanking cherry, although I was too young at the time to partake!)

Cold hardiness is never an exact science as there are many variables. But this is a very cold hardy plant, surviving winter temperatures as low as -40°C (-40°F).

Pick a Location for your Nanking Cherry

Sunlight: Full sun is best. As with many crops, if you only have partial sun, it’s worth a try. You’ll still likely get something.

Soil: Well-drained soil, enriched with compost.

Snow load: Winter snow coverage is, if anything, helpful, as it insulates the bush. I have one next to my driveway, and it’s covered every year with heaps of snow.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

Prune Nanking Cherry

One of the things that makes fruit bushes far more suited to home gardens is that the burden of pruning is less. You can prune annually if you want – and you’ll be rewarded with a nicer form and more yield. But if you’re busy and don’t get around to it, that’s fine too.

Timing: Prune in late winter.

Size: Remember, as the gardener, you decide the final height of your Nanking cherry bush. Depending on the growing conditions, it will get to 1.5 – 3 metres high (5 – 10 feet). Bushes can get fairly wide if space permits.

I keep mine pruned to about 1.5 metres (5’) high. That’s because I don’t want it to block the sight line between my garden and the sidewalk. And another important consideration is not to let the bush get any higher than you can pick!

In general, pruning that encourages young branches encourages more fruit. Keeping the canopy open with pruning helps to minimize the chance of any diseases because there is good air circulation. Pruning tips:

Remove some of the older branches

Trim out dead branches

Cut out crossing branches

Prune to shorten the bush

Nanking Cherry Pests and Diseases

Nanking cherry is in the same family as cherries and plums, which are affected by a number of pests and diseases. But I’ve never found the need for pest or disease control.

The one challenge I occasionally encounter is branch dieback where leaves on a branch dry up, and the branch eventually dies. Some sources attribute this to fungal diseases. For dieback, prune affected branches back to the main stem.

Harvesting Nanking Cherries

We eat lots of our Nanking cherries right in the garden! But they are versatile in the kitchen too.

Nanking cherries are an early summer fruit. Around here, that means that I’m picking them around the same time as strawberry season is finishing up.

Unlike sweet and sour cherries, where the stem is left attached to the fruit when picked, the stubby little stems on Nanking cherry stay on the bush. As a result, the fruit don’t last as long as other cherries.

Nanking Cherry in the Kitchen

The kids and I sometimes stand around a bush and guzzle cherries and then see who can spit the seeds the farthest. And that’s an important point I should make: like all cherries, there’s a pit!

Use Nanking cherries for whatever recipes call for sour cherries. I also freeze some for winter use. Because of the size, they are a bit fiddlier to pit than larger cherries.

Here are ways we enjoy using Nanking Cherry:

Nanking cherry juice

Nanking cherry compote

Nanking cherry bump (not for the kids!)

And…one other food related idea: I consider cherry wood the finest wood for smoking meat. So when I prune my Nanking cherry, I keep the branches to use for smoking.

Nanking Cherry FAQ

Do I need more than one Nanking cherry bush?

Many sources report the need for two bushes for cross pollination. I started out with one bush – the only one in the neighbourhood – and had good fruit set. There are reports of some self-fertile varieties.

When should I move my Nanking cherry bush?

The best time to move it is in the spring, while it’s still dormant.

Can I grow my Nanking cherry bush in shade?

It will grow best in full sun, but can grow respectably well in part sun/shade. Just know that you probably won’t get as much fruit as you would if it were growing in a full-sun location. As home gardeners we don’t always have perfect conditions.

Can I grow my Nanking cherry in a wet location?

Well drained soil is best. If the water table is high, consider growing in a raised bed.

What about animal pests eating the Nanking cherries?

The birds will like them just as much as you do. But unlike large tree fruit, such as apples and peaches, there’s much more to share when we grow small-fruited crops such as cherries.

Should I cover my Nanking cherry if there’s a frost?

The flowers are early in the season, when the risk of frost is still high. Most years I still get good fruit set here in Toronto. I’ve had reduced fruit set caused by a freeze once in a dozen years.

Is there a Nanking cherry tree?

Nanking cherry naturally grows as a bush.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More on Growing Cherries

Find out about 5 Types of Cherry Bush to Grow in Edible Landscapes and Food Forests

Hear Dr. Ieuan Evans talk about the Evan’s Cherry

More on Growing Fruit

These Courses Can Help you Grow Your Own Fruit

Edible Native Plants...and My Quest for a Rare Toronto Persimmon Tree

Native North American Fruits and Nuts (including persimmon and pawpaw!)

By Steven Biggs

Ontario Native Edible Fruits and Nuts

Pointing to two trees, Tom Atkinson explains that we have the makings of a golf club.

“There you have the shaft of the club; here you have the head,” he says, pointing from one tree to the other:

The shagbark hickory, with a bit of give in the wood, is ideal for the shaft.

The American persimmon, as part of the ebony family, has extremely hard wood that is suitable for whacking the ball.

Both are native North American species; and both have edible parts.

Hunting Pawpaw and Persimmon in Toronto

Our tree trek today is the result of my interest in another North American native, the pawpaw tree.

Because of my fascination with pawpaw, I tracked down Atkinson, a Toronto resident and native-plant expert, whose backyard is packed with pawpaw trees.

After I visited his yard and soaked up some pawpaw wisdom, he mentioned a fine specimen of American persimmon growing here, in Toronto.

I took the bait.

Under a Toronto Persimmon Tree

Now, in the shadow of that persimmon tree, I’m learning far more from Atkinson than persimmon trivia:

The nut of the shagbark hickory, a large native forest tree, is quite sweet.

He points to a pin oak, explaining that the leaves are often yellowish here in Toronto, where such oaks have trouble satisfying their craving for iron.

Waving toward a couple of conifers, Atkinson explains that fir cones point upwards, while Norway spruce cones point down.

There’s stickiness on the bud of American horse chestnuts, but not on their Asian counterparts.

And while the buckeye nut is normally left for squirrels, he’s heard that native North Americans prepared it for human consumption using hot rocks.

Landscape with Fruit

That’s easy to grow in a home garden!

A Backyard Native Fruit Food Forest

In his own garden, Atkinson’s focus is on native trees and shrubs. Many of them are considered Carolinian and are, here in Toronto, at the northern limits of their range.

My own interest in native trees and shrubs has gustatory motivations, but Atkinson’s came about because of his woodworking hobby. “I thought, if I was using wood, I should be putting it back,” he explains. While no longer woodworking, he still has a garden full of native trees and shrubs.

The edible native North American fruit and nut trees in his backyard food forest include sweet crabapple, black walnut, bitternut hickory, red mulberry and beaked hazelnut. “It is really for the creatures of the area, all this bounty,” he adds. I’m taken aback by his generous attitude towards harvest-purloining wildlife, but it’s consistent with his approach of putting something back.

Find out about elderberry, a native fruit bush.

American Persimmon

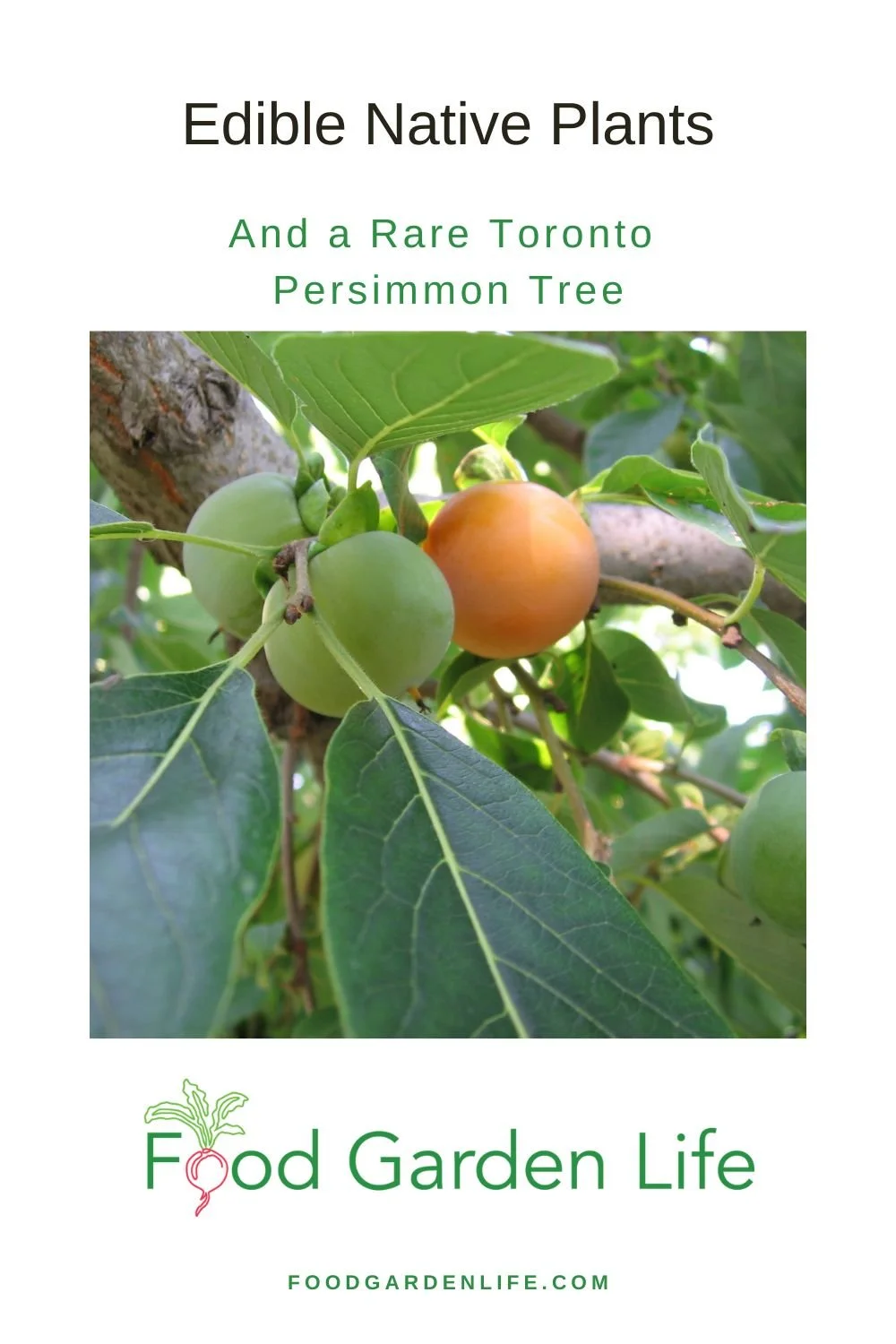

In the shadow of an American persimmon in Toronto. Grow persimmon in the warmer parts of Ontario.

Sitting under the American persimmon tree and looking up, I’m dismayed to find that the fruits are still green. Atkinson cautions that the fruit are astringent and bitter when unripe, so I satisfy myself with snapping pictures.

He explains that although this is a native North American species, it doesn’t usually grow wild this far north. But it grows well under cultivation.

(I found ripe, orange American persimmons a week later at Grimo Nut Nursery in Niagara, where the more temperate climate aids in ripening fruit earlier than in Toronto. They are sweet and velvety on the tongue; I’m delighted that the young persimmon tree I’ve been nurturing in my garden will have been worth the effort when it starts to fruit. And the fruit-laden trees are beautiful.)

Pawpaw

Atkinson's Toronto backyard, where he grows pawpaw trees and other native fruit trees.

Pointing to clusters of mango-like fruit, Atkinson says, “The fragrance of the pawpaw when ripe is aromatic.” He finds that the texture is like custard.

Each fruit usually contains four to eight seeds. “Like a watermelon, spit out the seeds,” Atkinson adds.

Don’t wait too long to pick it. “If it’s starting to turn brown, give it to the squirrels or raccoons,” he advises.

Pawpaws can be found growing wild on the north shore of Lake Erie into the Niagara region. Like the American persimmon, you’re not likely to find wild ones here in Toronto, but they do grow well here when planted. The large, lush leaves add a tropical feel to the garden.

Serviceberry

Serviceberry is a native edible plant well suited to growing in the city.

When it comes to native edible plants, Atkinson believes that one of the best to grow in the city is the serviceberry.

“There’s a whole bunch of them,” he explains, listing the related members of the serviceberry (Amelanchier) clan. They all have in common an edible fruit similar in size to a blueberry.

Palatability varies by species and variety. The saskatoon berry, which is also grown commercially, has consistently good fruit quality, according to Atkinson.

Serviceberry is widely planted in Toronto parks and is common in the nursery trade. They can be grown as a small tree or a bush.

In my own garden, I end up sharing my serviceberry harvest with robins if I don’t pick them quickly enough. Atkinson says that cedar waxwings like them, too.

Aside from the fruit, the serviceberry leaves turn a vibrant orange-red in the fall and the bark, smooth and grey, is showy, too.

Here’s a member of the serviceberry family that’s grown as a commercial crop: Guide to Growing Saskatoon Berries: Planting, Pruning, Care

American Hazelnut

American hazelnut is a native nut bush. It’s related to the European hazelnuts sold in grocery stores, but the nuts are smaller.

Hazelnuts send out attractive catkins in late winter, before any leaves are out.

Crabapple

“They’re a delight to look at,” agrees Atkinson as we change gears and talk about the sweet crab, a wild crabapple. “It puts on a really good show of flowers,” he says as he describes a blush of pink on white flowers in the spring, adding, “It’s as good as a flowering dogwood but in a different sort of way.” The fruit is very waxy, and very attractive, having a greenish yellow colour.

“Squirrels don’t touch it,” he exclaims. He likes the fall leaf colours, which range from yellow to burnt orange.

On the culinary side, he says the sweet crab fruit is sour, but a perfect accompaniment when roasted with a rich meat such as pork, where the tartness of the fruit cuts the richness of the meat.

Black Walnut

Atkinson speaks warmly of towering black walnut trees and of the beautiful dark wood they yield. He notes how common they are in the Niagara peninsula: “They’re almost like weeds.”

I agree with the weedy bit: My neighbour’s black walnut stops me from growing anything in the tomato family at the back of my yard. Despite its hostile actions towards my tomatoes, I have grown fond of sitting under that tree, never really considering why. “The shade under a walnut is really quite lovely,” he says, describing dappled light that results from the long leaf stalks adorned with small leaflets.

He discourages me from promoting the black walnut for edible uses because the nut meat is very difficult to extract: the shells are rock hard, requiring a hammer to crack. And the meat doesn’t come out easily like an English walnut, but has to be picked out. But by this point I’ve already decided to write about edible native plants because of their ornamental appeal.

Read about wicking beds, a way to deal with black walnut toxicity, a.k.a. juglone.

Growing Native Fruit in Urban Areas

I thank Atkinson for the tour and email correspondence. A couple of weeks later, Atkinson emails me a photo of a broken pawpaw branch. He writes: “Steve, here is what befalls a pawpaw when in an urban setting, and there are hungry raccoons about. I do not begrudge my masked friends at all for doing what inevitably they will do when after pawpaws.”

FAQ American Persimmon

Can persimmon grow in Ontario? Can you grow persimmons in Canada?

American persimmon is reported to be hardy into Canadian hardiness zone 4, though a long growing season with summer heat is needed for fruit ripening. Best in zones zones 5b-8.

Remember: Zones are only a guideline. Sometimes you can cheat if you have a warm microclimate.

Can I grow a persimmon tree from seed?

If you grow American persimmon from seed, the main thing to remember is that they are “dioecious.” This just means that a plant can be male or female. If you grow a seed and get a male plant, you won’t get fruit from it.

Many commercial varieties produce fruit without a male.

Interested in Forest Gardens?

Here are interviews with forest garden experts.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

More Information on Growing Fruit

Articles and Interviews about Growing Fruit

Courses on Fruit for Edible Landscapes and Home Gardens

Home Garden Consultation

Book a virtual consultation so we can talk about your situation, your challenges, and your opportunities and come up with ideas for your edible landscape or food garden.

We can dig into techniques, suitable plants, and how to pick projects that fit your available time.

Guide: How to Grow Sorrel (& How to Use it!)

Find out how to grow sorrel, and get ideas for creative sorrel recipes.

By Steven Biggs

Planting Sorrel: An Easy-to-Grow Perennial Vegetable

Sorrel is one of my favourite crops because it checks off a number of important things for me:

It’s easy to grow (it’s a perennial that comes back year after year)

It’s difficult to find fresh sorrel leaves in stores (and if you find them, they’re expensive)

It is versatile in the kitchen (soups, meat, salads, and more)

(And I've cooked with sorrel on TV!)

Sorrel also has a rich herbal history, with a variety of uses.

I’m no herbalist, so in this post I’ll tell you how to grow sorrel and give you lots of ideas for using it in the kitchen.

Haven’t Seen a Sorrel Plant? You’re Not Alone!

Garden sorrel is a hardy perennial.

Sorrel is a familiar ingredient in European cuisine. That’s how it came to North America—with European settlers.

The “wild” sorrel sought after by foragers is simply sorrel that’s escaped cultivation.

Yet many people in North America don’t know to sorrel.

If you’re new to sorrel, it’s grown for its leaves. It’s sour leaves. I think of it as a lemon substitute for northern gardeners.

When I shop at eastern European shops, I see jarred sorrel…horrid sludge. I don’t recommend it. Grow yourself fresh sorrel!

Grow your own sorrel, and skip the brined sorrel!

But it was an eastern European connection that go me growing sorrel. As a teen, I took Ukrainian lessons (hoping to learn my mom’s first language—which she never taught us.) I never did pick up the language—but the teacher, who knew I was a gardener, couldn’t believe I’d never heard of sorrel. And brought me a clump of this plant that she said was an essential ingredient in the old country.

What is Sorrel?

Sorrel is a hardy perennial plant that grows in a clump. It’s tough as nails, hardy into Canadian zone 4.

The long, narrow leaves are ready to pick early in the season, making it one of the first greens to harvest.

You can use the leaves fresh—or cook with them. (See How to Use Sorrel, below.)

Types of Sorrel

There’s more than one type of sorrel. Here are three common ones:

Garden sorrel leaves can be over 30 cm long when plants are in moist, rich soil.

Garden Sorrel (Rumex acetosa). Garden sorrel was brought to north America by European settlers. It's grown in gardens, but is also an escapee that can be found growing wild. Leaves reach 30-60 cm (12-24 inches) long, depending on the growing conditions.

Sheep Sorrel (R. acetosella). Sheep sorrel is another escapee. Sometimes called sourgrass. You might find it filling in exposed spots like vacant lots and roadsides. Seed stalks take on a reddish colour. Spreads by seed and running roots. This is the less-loved cousin to garden sorrel, with smaller, narrower leaves that have a distinct lobe at the base, a bit like an arrowhead. I wouldn’t plant this fast-spreading plant in the garden, but it’s an excellent edible, and popular with foragers.

French Sorrel (R. scutatus). French sorrel is also called round-leaved sorrel. The leaves are shield shaped. Plants are shorter than garden and sheep sorrel.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

How Sorrel Grows

Sorrel grows best in rich, moist soil, in full sun or partial shade. Though that doesn’t mean it won’t grow elsewhere…as evidenced by the behaviour of sheep sorrel in vacant lots!

But in a garden setting, give it water if it’s in a dry location. If it’s in partial shade, you won’t need to water as much.

Flower stalks turn into red-tinged seed spikes. Remove stalks to encourage young leaves—unless you want to collect sorrel seed. If you’ve been diligently removing flower stalks, you’ll be able to continue harvesting for the whole growing season, until the plant shuts down for winter—when the top dies back with fall frosts.

Where to Grow Sorrel Plants

Because sorrel is ready to harvest early, I like to have mine close to the kitchen.

Growing Sorrel in Perennial Borders

As a perennial plant, sorrel is at home in the perennial border. Stick it at the front so it’s easy to reach.

Sorrel in the Vegetable Patch

A row of garden sorrel with seed heads. See the red tinge?

I don’t plant sorrel in my main veggie patch, where I move around crops from year to year. Because it is a perennial plant, I grow sorrel around the periphery, with the rhubarb and asparagus—other perennial vegetables.

I’ve seen an entire row of sorrel plants used as a border in a formal edible garden.

Find out more about perennial vegetables.

Sorrel in the Herb Garden

Garden sorrel and French sorrel are well behaved plants that make a nice addition to a herb garden.

Looking for vegetable garden planning ideas? Here are articles to help you plan and design your vegetable garden.

How to Harvest Sorrel

Young sorrel leaves in the spring are the most tender.

You’ll get the best flavour and texture in spring, from young leaves.

But you can harvest sorrel until fall frosts shut the plant down for winter.

How to Propagate Sorrel

There are two ways to propagate sorrel plants.

Division. When a clump is big enough, divide it in the spring.

Seed. Sow sorrel seeds indoors in early spring. Move to the garden after the risk of frost has passed. Space plants about 30 cm (1 foot) apart in the garden.

FAQ: Sorrel Plants

Will Sorrel Grow in Shade?

Sorrel grows in full sun and partial shade. Because it produces larger, more tender leaves in moist soil, semi-shaded conditions are a good option where conditions are hot.

Are sorrel and hibiscus the same?

An unrelated plant, Hibiscus sabdariffa, also goes by the name sorrel. It’s tangy flowers are used in Caribbean cuisine.

Can I forage for sorrel?

In North America, both garden sorrel and sheep sorrel grow wild.

If you’re interested in foraging, listen to our chat with foraging expert Robert Henderson.

What are oxalates?

Wood sorrel is of no relation to garden sorrel, but it, too, has a sour tasting leaf.

Sorrel contains oxalic acid, a compound also found in spinach and rhubarb. If you go overboard and eat too much, it can cause tummy upset. That means don’t be a pig. You wouldn’t eat a whole bowl of lemons, would you? Consume it with other foods. It’s for flavour—not the main course.

One other thing about oxalic acid is that it can provoke existing joint and kidney problems. So if you have a history of kidney stones, skip the sorrel

What about wood sorrel?

Related in name only, wood sorrels (Oxalis sp.) can be grazed too.

Bloody dock is also known as red-veined sorrel.

Is bloody dock a sorrel?

Bloody dock, R. Sanguineus, is also known as red-veined sorrel. It’s related to sheep, garden, and French sorrel.

But don’t waste a second on it. Unless it’s as an ornamental. (It's quite beautiful.) You’ll find shoe leather that’s more tender than bloody dock leaves.

How to Use Sorrel

Before we get to using sorrel in the kitchen, enjoy sorrel while you’re in the garden. You can graze as you garden. The tangy leaves are refreshing.

Because sorrel is tangy, it pairs well with rich food.

Here are ways to use sorrel:

Use sorrel leaves in salads (I find a sorrel-only salad a bit too tangy, so I mix it with other greens)

Sorrel leaves in sandwiches

Sorrel soup (see recipes below)

In recipes that call for greens such as spinach or lambs quarters, substitute part or all of the greens with sorrel (I add it to my Swiss-chard-and-leek spanakopita)

Add it to sauces for a lemony flavour (I throw in pieces of sorrel leaf when braising meat)

Add sorrel leaf bits to an omelette or frittata

Chop and freeze for use through the winter

I’ve seen a recipe for devilled eggs that includes bacon and sorrel…sounds divine

Gourmet butter: Finely chop sorrel leaves and mix in with soft butter

Making a ranch-style sour-cream or yogurt dip? Add chopped sorrel

Make ordinary pesto shine by adding a bit of sorrel (oh yeah, pairs nicely with blue cheese!)

Sorrel Recipes

Sorrel Soup

Pin this post!

Here’s an easy-to-make sorrel soup recipe.

Ingredients

3 tbsp. butter

1 onion, chopped

3 potatoes, cubed

3 cups sorrel leaves, stem removed

8 cups broth

½ cup sour cream

Salt and pepper to taste

Directions

Fry onion in butter until golden

Add potato, sorrel, broth and simmer (covered) for about 15 minutes, until potatoes are soft

Puree (I use a hand immersion blender)

Whisk in sour cream

Heat to serve (don’t boil)

Sorrel Vichyssoise Soup

If you want to take sorrel soup to the next level—and use some of your homegrown leeks—this take on the creamy potato-leek classic is delicious.

Sorrel vichyssoise soup, topped with a sorrel leaf, a dollop of sour cream, and edible redbud flowers.

Ingredients

2 tbsp. butter

3 cups of sorrel leaves, stem removed

1 large leek, chopped (use both white and pale green parts)

1 onion, chopped

3-4 potatoes, cubed

4 cups water or broth

2 tbsp. salt

4 cups whole milk (use cream if you want something more decadent)

Directions

Fry leek and onion in butter until onion is golden

Add potato, salt, water/broth, sorrel and bring to a boil

Simmer until potatoes are tender

Stir in milk, and then puree

Serve chilled

When serving, I like to float a dollop of sour cream on top, alongside a raft of croutons.

Sorrel Paste and Sorrel Soup

Hear this interview with forager Robert Henderson, who talks about how to make sorrel paste and sorrel soup.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Courses

Edible Garden Makeover. Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

Container Vegetable Gardening Masterclass. Here’s a course that gives you everything you need to know for container vegetable gardening success.

Skip the Transplants: Direct Sowing Seeds

Find out how and what to direct seed in your vegetable garden.

by Steven Biggs

Why Direct Sow Seeds?

Ever had transplants that put on the brakes after you move them to the garden?

It’s disappointing.

But a big transplant isn’t always better than a wee seed.

Sometimes, it’s better to plant seeds straight into the garden.

This is called direct sowing (or direct seeding.)

This post tells you how to direct sow, best crops for direct sowing—and simple ways to sow seeds in a home garden.

What is Direct Sowing?

Direct sowing is when we sow seeds directly in the garden.

This is instead of starting seeds indoors—known as growing “transplants.”

Why Direct Sow Vegetable Seeds?

There are many reasons to direct-sow vegetables.

Here are a few reasons:

Pin this post!

Easier (there's no need to care for seedlings indoors)

Less expensive (no need for potting soil or containers)

Less environmental footprint (yeah, your coir-based and peat-based potting soils have an environmental footprint)

Saves indoor seed-starting space for crops that really need to be started indoors

No need to “harden off” young seedlings before planting them in the garden

Some crops don’t transplant well…and don’t bounce back well from transplanting

When Direct Sowing is NOT the Best Choice

Direct seeding isn’t the best choice for all crops, or in all situations.

Here are a few things to consider:

In areas with a short growing season, crops that take a long time to mature are grown from transplants

Slugs and other bugs can devastate small, direct-sown seedlings as they emerge…whereas a larger transplant might get through some insect damage

During hot summer weather, seed germination can be spotty (see below for a summer seed-sowing hack)

In low-lying area, the garden soil might be too wet to plant seeds in the spring

You’re new to gardening and won’t know the difference between emerging direct-seeded crops and the weed seedlings!

How to Direct Sow Seeds

Before sowing seeds, prepare the soil.

Start by preparing the soil ahead of time. When sowing seeds, we want to break up any crust on top of the soil surface, and break up bigger chunks of soil. That way, germinating seeds don’t hit roadblocks.

(Yes, there’s a whole body of work out there on no-dig techniques—and there is a time and place for this…but if you want the best results when planting seeds, prepare the soil.)

Planting Depth

Use the size of the seed as a guide to planting depth. Seed packets usually recommend a depth too.

Plant the seed about twice as deep as it is wide. Too shallow is better than too deep.

But don't feel as if you need to measure and be precise.

If you’re planting seeds into trenches, you can make well-spaced trenches using a garden rake that has pieces of pipe on it.

Like most things in gardening (and life), direct sowing isn't an exact science.

Trench for Sowing Seeds

If you direct-sow seeds in rows, make a trench with your trowel or the corner of a hoe.

Then, place your vegetable seeds into the trench, and cover with soil.

OR, make your trenches by fitting pieces of pipe onto a garden rake!

Poke Seeds in the Soil (Planting Seeds Simplified!)

This is low-tech and might be laughable to a commercial grower—but in a home-garden setting, can be a simple approach to direct sow seeds!

I drop large seeds into place, and then just poke them into the soil. Then I scuff the soil to fill the holes.

Poking works well for larger seeds that you can easily see:

Poking large seeds into the soil is a simple way of planting seeds.

Peas

Beans

Beets

Swiss chard

Squash

Zucchini

If you’re planting a whole block with seeds, as I like to do with beets and Swiss chard, you can do what I call the “scatter-and-poke” method. Scatter seeds to approximately the spacing you want—and then poke them into the soil. Scuff soil to fill in holes.

(Gardening is a great cure for perfectionism, and the scatter-and-poke approach dispenses with all notions of perfection in a garden!)

Broadcast and Cover

You can sprinkle small seeds such as these carrot seeds by hand, and then cover with soil.

If you’re filling a block or wide row with small seeds (e.g. carrot or lettuce), sprinkle by hand, and then cover with soil.

You might wonder, “Where do I get the soil I’m covering the seed with?” Rake aside some garden soil before you sprinkle your seed in place—and replace it over top of the seed afterwards.

Broadcast and Rake!

I’m always interested in methods that make my life simpler. And raking aside soil before I broadcast seed is a bother.

So I simply broadcast the seed, and then use an up-and-down motion with a hand rake to work some of those seeds into the soil.

Note: There will be some seeds that aren’t at an ideal depth. That’s OK. I’m a home gardener—not a commercial grower. I just seed more heavily to compensate.

Direct Sowing Hacks

Using a broadfork to make straight rows.

Folded paper. Forget the seed-dispensing gizmos for small seed. Fold a sheet of paper in half. Pour seed onto the folded sheet. Now, use a pencil or a nail to dispense individual seeds off the end of this folded sheet. Low tech, yes—but works well.

Broadfork. When my daughter, Emma, wanted side-by-side trial rows of a number of crops, she used the broadfork to make a tidy set of trenches. (The broadfork is normally used to loosen soil…but this works nicely!)

Seed tape. Seeds embedded in a strip of biodegradable paper. Yeah, a bit gimmicky. I don’t use this. But if you’re gardening with kids, or you have shaky hands and can’t easily dispense seed, it can be useful.

Using boards to keep the soil moist for direct seeding in the summer.

Pelleted seed. Small seeds bulked out with a clay coating. Like seed tape, you pay more per seed. But again, could be useful if you’re direct seeding with kids, or you’re having trouble coping with smaller seeds.

Boards. Yup, low-tech boards over summer-sown small seeds can be a life saver. In summer heat, soil can quickly form a crust that seedling have difficulty breaching. But a board over the soil during the germination window keeps the soil underneath moist. No crust.

Web trays. As soon as squirrels see freshly turned soil in my garden, they’re eager to disinter seeds. It’s infuriating. Who would have thought there’s a higher purpose for those horrid plastic webbed trays that the horticulture industry so loves! Inverted web trays over top of your directly sown seeds keep digging varmints at bay.

Direct Seeding by Crop

Take that, squirrels!

Leafy Greens. I grow transplants of leafy green crops such as lettuce, spinach, and Swiss chard. I also direct-sow seeds into the garden.

Why both ways?

So I have a succession of harvests.

(It is also insurance. If weather or pests cause less successful results one way, I have a backup!)

Root Crops. I direct sow all my carrots, parsnips, and beets. These crops can all be direct-sown in the garden early. And they don’t respond well to root disturbance.

“Fruit” Veg. For those fruits that we insist on calling veg—tomatoes, peppers, and eggplant—I grow everything by transplants because I’m in a cold climate and I extend the harvest window with transplants.

Vining Crops. The vining crops in the squash and cucumber clans don’t respond well to root disturbance. So direct sowing is always a good strategy.

(But, like the leafy greens, I hedge my bets and both direct sow and start a few transplants.)

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Courses

Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

Move Over Bedding Plants...and Try These Edible Garden Plants Instead

Replace some of your bedding plants with edible plants! Find out how to choose suitable crops to use as bedding plants.

by Steven Biggs

A Few Plants for Edible Landscaping

Attractive? Check.

Low maintenance? Check.

Edible? Check.

The peppers were the finishing touch in my front-yard edible landscape. Right by the sidewalk. A nice pop of colour.

What had been my front lawn three months before was an edible front yard—edible plants including salad greens, herbs, vegetables, fruit bushes, and edible flowers.

I was enjoying the mix of colour, height, and texture as I popped one of those peppers into my mouth.

Sound the fire alarm. My face lit up scarlet. I grabbed a basket and, between hiccups, plucked all those hot peppers…worried about hot-pepper misadventures with the school kids that go by twice a day.

So the hot peppers were not a home run.

But with those little scorchers harvested, I left the pepper plants. They had dark green leaves and compact form. Nice bedding plants nonetheless. Just not next to the sidewalk.

If you’re interested in edible plants for edible landscaping, keep reading. This post gives you design ideas and top crops for using as edible bedding plants.

What’s a Bedding Plant?

Bedding plants are display plants for seasonal plantings. Here’s a good example, at Butchart Gardens in BC.

Bedding plants are display plants for seasonal plantings. Garden bling. So choices usually combine fast-growing, colour, and resilience.

Some, like coleus, have fabulous foliage. Many have showy flowers. Commonly they’re flowering annuals—though not always. Others, like fuchsia, are tender perennials.

But what they have in common is that they’re typically transplanted into a garden to give an immediate show. Then they’re yanked out at the end of the season.

Lots of common vegetable-garden and herb-garden plants can fit the bill as bedding plants in an edible landscape.

What Makes a Good Bedding Plant?

A good bedding plant is low maintenance. It doesn’t need pruning or staking. You don’t need to hold its hand.

For summertime plantings, a good bedding plant also performs well through the heat of the summer.

Why Use Edible Plants as Bedding Plants?

Using edible plants to make ornamental plantings—instead of traditional bedding plants.

I have nothing against flowers. I go overboard planting flowers every year.

But like many home gardeners, I never have enough space to grow all of the plants I want to grow.

So if I can kill two birds with one stone—edibles for both eating and appearance—count me in. Give me space in the flower garden for some veggies…I'll make it into an edible landscape.

Bedding Plants Through the Seasons

Pin this post!

Most ornamental bedding plants are planted after the last spring frost, but there are exceptions. The most common is pansies—which shine on despite a frost.

(If you didn’t know, pansy flowers are edible!)

You might see plantings of ornamental kale and cabbage in the fall. They soldier on through fall frosts while most bedding plant snivel.

(You can eat ornamental cabbage and kale—though they’re bred for looks, not as gustatory delight.)

Just as plant choice can keep the curtains open longer for a flower garden, choosing the right edible bedding plants keeps an edible landscape looking tip-top into the fall.

Designing Edible Landscapes with Edible Bedding Plants

Swiss chard hanging out with some ornamental bedding plants.

The way you use bedding plants depends on the situation and your taste (sorry about the pun.)

My advice? Be wildly creative and do something that your neighbours aren’t doing. Gardening can be more than practical; it can be creative, too.

(It should be creative, that’s the fun part!)

To get your creative juices going, here are three broad ways of using bedding plants in your edible landscape:

Formal. Think of public display gardens with formal flower beds and symmetrical patterns. (If you’re a detail person, this might be up your alley.)

Informal. This is where you’re getting playful with colour and texture and not constrained by having one big formal flower bed. Like icing on a cake, you “ice” the garden bed…a smear of bedding plants here and there.

Carpet. I once worked at a company where we made the company logo from bedding plants. That’s carpet bedding. We’re talking about a tightly planted, intricate pattern. Like painting with plants.

5 Edible Bedding Plants to Start With

Here are five edible bedding plants you can start with. There are lots more (including the pansies and kale I mentioned above.) But these five edible plants are all work horses, easy to find, and give a good mix of colour and texture.

Swiss Chard. Such an underrated plant. While so many of its leafy-green brethren make haste to flower and die, Swiss chard just grows leaves all summer. And along with green varieties, there are red, orange, yellow—even striped red-and-white varieties. Find out why Swiss chard is also a great choice in the fall garden.

Swiss chard. This underused leafy green makes an excellent bedding plant.

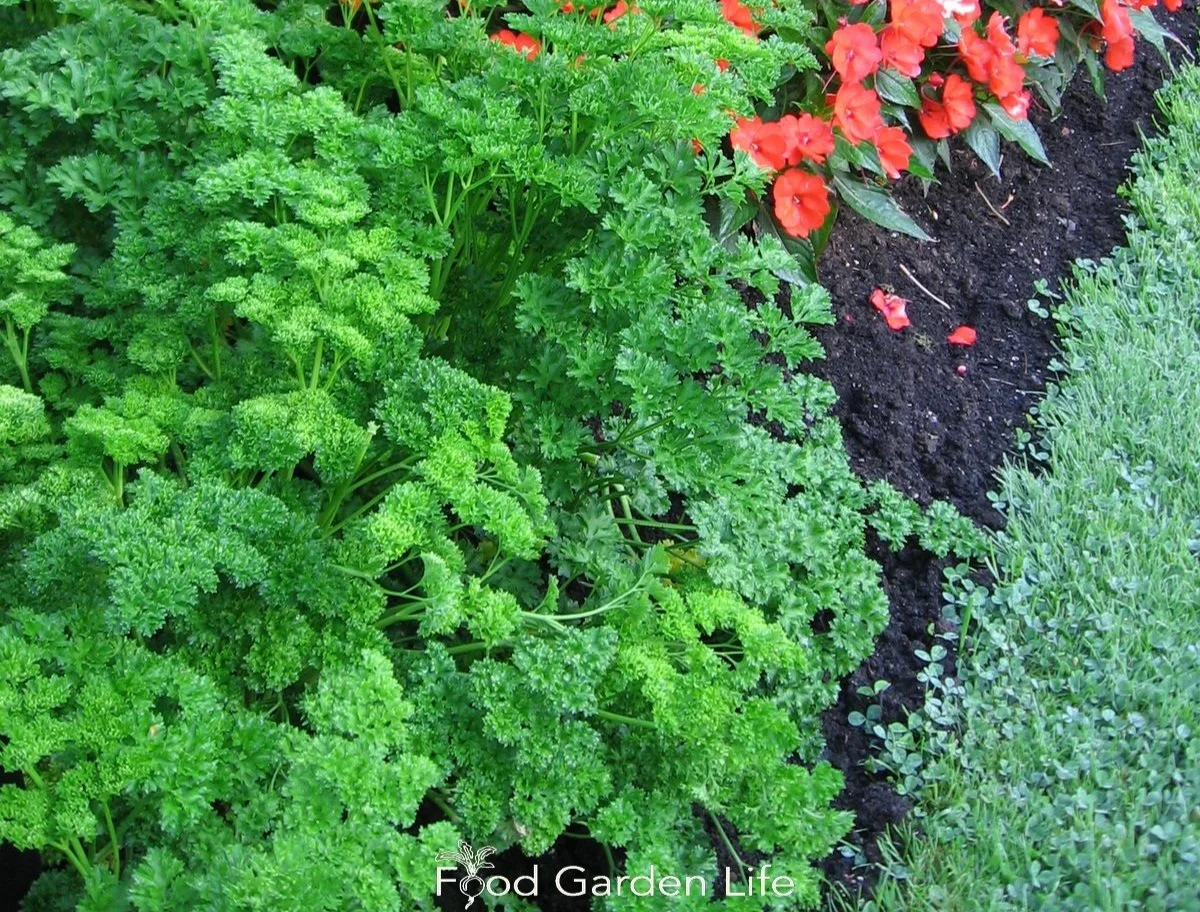

Parsley. The world needs more parsley. Seriously. Beyond garnishing a cheese tray or bulking out your bruschetta mix, parsley is a performer in the edible landscape. Great for edging borders. Planted in larger blocks, curly-leaf parsley is a brush-stroke of texture. And it lasts nicely even as fall frosts fell heat-loving crops.

Parsley. A top-notch bedding plant.

Cardoon. How many edible plants can you describe as elegant? This one has a touch of class. I was riveted when I saw cardoon punctuating the landscape of the historic Spadina House mansion in Toronto. What a bold beauty this plant it! Find out more about cardoon.

Cardoon. An elegant bedding plant!

Basil. From compact, little-leaf varieties to more gangly family members, you can choose from quite a range of plant and leaf sizes. And for leaf colour, remember there’s red and purple, as well as green. The compact basils are great for carpet-style designs. Keep in mind that basil, after a spell of cold fall weather, will quickly pack it in for winter.

Basil. So many choices…here’s a shot from a trial garden.

Eggplant. Compact plant. Attractive flowers. Beautiful fruit. Eggplant can be front and centre in an edible landscape. I love the small-fruited varieties with interesting colours, such as red-fruited eggplant or the skinny striped ones. Eggplant as a bedding plant? I bet your neighbours aren’t doing this!

Eggplant. Even if you don’t love eggplant, you have to admit it’s beautiful!

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your edible-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Courses

Here’s a course that guides you through creating an edible garden you love. It’s my ode to edible gardening. You’ll find out how to think outside the box and create a special space. Get the information you need about a wide range of edible plants.

A Dragon's Garden for Children (Toothy, Pointy, Spiny Plants!)

By Steven Biggs

Kids Gardening…with Fun Themes

A dragon-themed garden never occurred to me.

It was Finn’s idea.

Finn and him mom came to my daughter Emma’s talk about gardens for children.

She told the kids they didn’t have to garden like grown ups. They could make their gardens fun.

Grow a tickling garden with plants that are good for tickling

A purple garden

Or a giant’s garden with giant sunflowers and mammoth pumpkins

Then Emma told the kids about one of her favourite plants that year: a bean with unusual markings called ‘Dragon Tongue.’

Finn Decides on a Theme Garden

The next morning Finn’s mom sent us a note. He loved the ‘Dragon Tongue’ bean. He loved dragons.

So he decided he’d grow a dragon-themed garden.

Dragon Tongue beans for a dragon-themed garden. (Photo by Emma Biggs)

Emma and I loved Finn’s idea.

So we scoured seed websites for dragon-themed plants. Here’s what we came up with:

Dragon’s Egg cucumber

Purple Dragon carrot

Red Dragon arugula

Dragon’s Fire arugula

Tongue of Fire bean

Snapdragon…and there are so many sizes and colours

Dragon’s Toe pepper

Green Dragon cucumber

Thai Dragon hot pepper

Blue Dragon dracocephalum

Flower Dragon watermelon

Black Dragon coleus

Taking the Dragon Idea Further

Then we thought about how we’d describe a dragon. We came up with ideas like spiny, toothy, winged, and pointy.

That helped us find even more plant ideas for the dragon-themed garden:

Litchi tomato for spiny skin!

Toothy. (An agave looks pretty toothy to my imagination. Or, if you want to stretch things, dandelion comes from French—dent-de-lion—which means "lion's tooth.” I even found a daylily called ‘Snaggle Tooth.’)

Long and pointy for the tail. (Corn? …I’ll let the kids brainstorm this one.)

Leathery or spiny for dragon-like skin. (I’m picturing citrus rind here; and Litchi Tomato would be perfect!)

Serpent-like shape. (I think snake gourds might work!)

Wings (How about a winged bean, angel wing begonia…or maybe something with winged seeds such as maple?)

I’m sure there are lots more plants with a dragon connection. E-mail us if you have any to add to the list!

Another Themed Garden

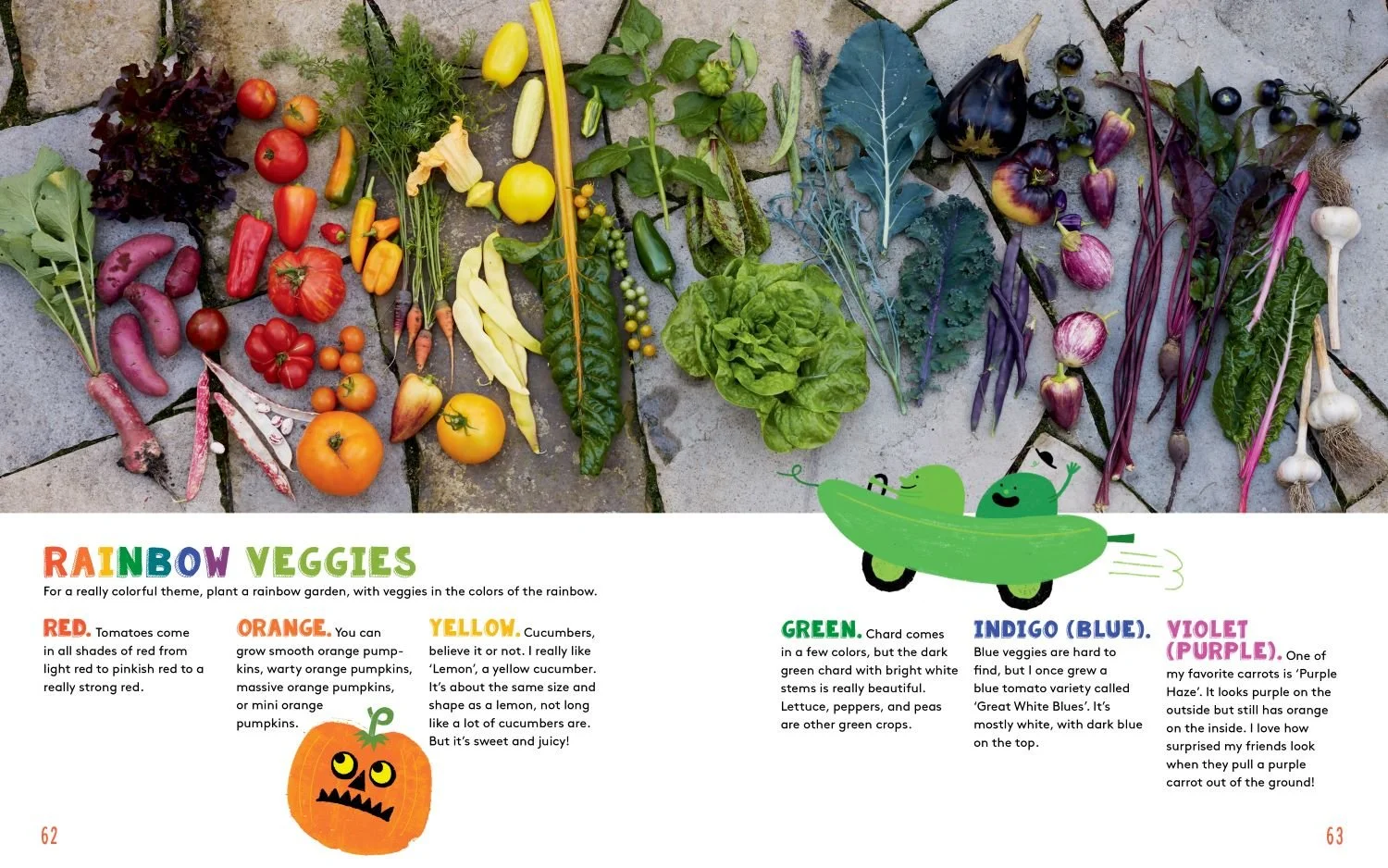

Check out the picture below of the harvest from Emma’s rainbow-themed garden.

A Rainbow-themed garden, from the book Gardening with Emma.

More theme ideas:

Pizza garden

Salsa garden

Bug’s garden (maybe include logs and rocks that kids can lift up to hunt for bugs)

More Ideas for a Garden for Children

Kids Gardening Articles and Interviews

Kids Gardening Books

Want fun books to inspire the kids in your life to explore the garden? Here are kids gardening books, signed by the author, Emma Biggs.

Driveway Makeover! 5 Ideas for Growing a Container Garden for Vegetables

A container vegetable garden is a good way to fit lots of vegetable crops into a small space. Find out how to get started.

by Steven Biggs

My Driveway Container Vegetable Garden

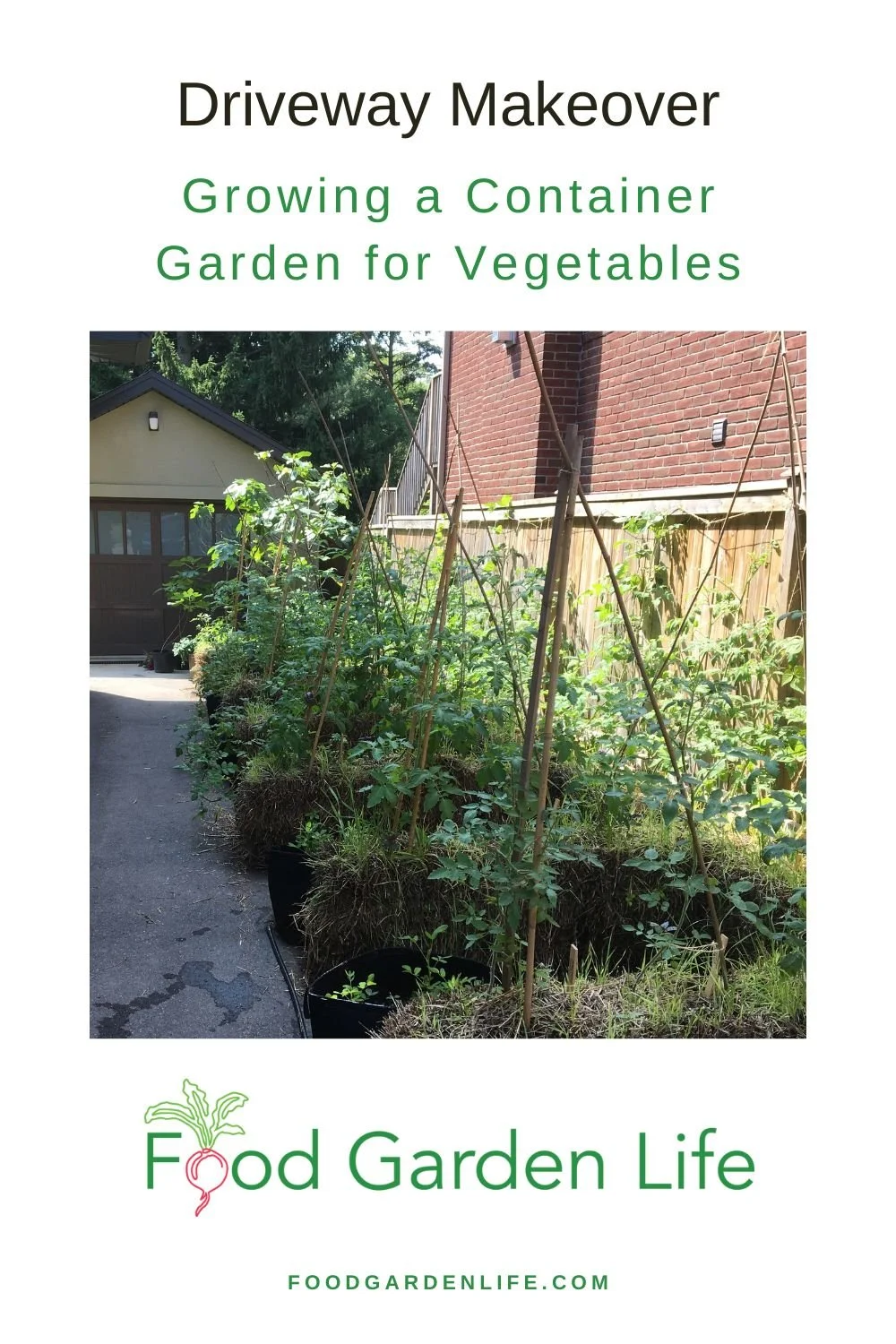

Not enough space to grow everything you want? Be creative! A container garden are a great way to fit more vegetables into your yard.

Here’s our driveway container garden. The driveway container garden is a quick, temporary space-making solution so we can grow extra tomato, pepper, potato, summer squash, and chard plants.

In this vegetable container garden, we use straw bales, fabric pots, nursery pots, bushel baskets, and vertical gardening techniques to make the most of the space.

In this post, I talk about these five vegetable container gardening techniques, along with container plants and container garden tips.

Ideas for Your Vegetable Container Garden

Container gardening is part science, and part creativity. There are lots of ways to approach it. Here are five ideas we’ve used to make the most of our driveway for growing vegetables.

1. Strawbale Gardens: Grow Vegetables in Containers that are Biodegradeable

Wetting the straw bales to start the “conditioning” process.

A lot of visitors take a second look at my straw-bale garden and wonder where I put the potting soil. There is no potting soil: The straw bale is both the container and the growing medium. No potting mix required!

The decomposing straw gives plant roots needed air while retaining moisture…like a big sponge.

By the end of the season, when we pull apart a bale, the inside is dark and crumbly. It’s already partially composted and perfect to use as mulch on our gardens. Then, we start again with new bales the following year.

We plant the top with tomato plants and leafy greens. Then we put bush beans on the sides of the bales.

Important: If you’re starting with new, fresh, dry bales, the first step is to get microbial activity underway by watering them and feeding them. This step is called “conditioning.”

Find out more about straw-bale gardening.

2. Bushel Baskets: Growing Vegetables in Containers that are Repurposed

Container vegetable gardening with repurposed stuff! Potatoes growing in lined bushel baskets.

We often have extra bushel baskets from our fall cider-making. So we use them for growing potatoes. (We can’t grow potatoes in our back yard because our neighbour’s black walnut tree gives off a compound that kills them.)

We line the bushel baskets with plastic bags so that the potting soil stays moist longer and so the bushel baskets won’t decompose as quickly. (We poke drainage holes in the bottom of the bags!)

There are lots of repurposed items that work well as containers. Here are a few ideas:

Milk crates. I’ve used these in previous gardens. Just cover the openings on the side and bottom with newspaper or cardboard, so the soil doesn’t escape.

Old wheelbarrow. A friend uses an old wheelbarrow as a driveway planter.

Wash basins. I have neighbours who use metal wash basins as vegetable garden planters. (Make sure to drill drainage holes in the bottom.)

3. Fabric Pots: Garden in Pots that are Moveable

Fabric pots are moveable, and a great way to start container gardening.

These pots are widely available. What we like about them is that they have handles so we can move them aside if we need to move anything large along the driveway.

I’ve seen impressive rooftop container gardens created with fabric pots. While some gardeners use drip irrigation to keep the soil consistently moist, a more simple approach is to put a saucer underneath; as the potting mix begins to dry, water in the saucer wicks upwards.

4. Fence: Grow Vegetable Plants on Surrounding Features

We train tomato plants up the twine that is dangling from the top of the fence.

Sometimes it’s possible to squeeze more crops into a space by growing some of them upwards—a concept that’s often referred to as “vertical gardening.” In the case of our driveway, there’s a wonky board fence that I like to hide with a wall of tomato and squash!

We plant tomatoes next to the fence, and then train them up twine suspended along the fence. We also grow squash vines along the fence—well past where the garden is.

Idea: I’ve also grown squash along hedges and up trees. Because the vines roam around, there are lots of vertical-gardening possibilities.

Here’s more about vertical gardening.

5. Nursery Pots: Figs Growing in Containers

Next to my garage is my potted fig “orchard.” It’s a collection of potted fig plants growing in nursery pots. These fig trees spend the winter in my garage.

Nursery pots are an inexpensive way to start container gardening. Talk with garden centres and arborists—you can often get them for free or very inexpensively.

If you’re interested in growing figs in a cold climate, here’s more about how to do it.

Grow a Container Vegetable Garden

And get an early harvest of crops that usually take too long!

Plan Your Container Vegetable Garden

Choose the Location

If you’re thinking about a container vegetable garden but don’t know where to start, choose your location first.

Then, once you’ve decided on a location, you’ll know how much sunlight you’re dealing with. Remember that full-sun crops such as tomatoes can do respectably well in partial sun. (This is not something a commercial market gardener would do…but if you’re a home gardener, conditions often aren’t perfect.)

Something else to think about is access to water. Is there a tap or hose nearby?

Choosing Container Plants

When it comes to choosing container gardening crops, a good starting point is things you like to eat.

Then, think about crops that do well in containers. Most vegetables grow well if a container is big enough, but some crops are more practical than others.

For example:

Pole beans are great if they're next to something they can grow on, but, otherwise, bush beans are more practical because you don't need to make a trellis.

Parsnips and Brussels sprouts take the whole summer and fall to mature. Instead, look for crops that mature more quickly, like carrots and carrots.

Here’s a list of best vegetables to grow in pots.

If the location is shady, here’s a list of crops that grow in shade.

Consider Containers with Reservoirs

A key to success—and common reason for failure—with container vegetable gardening is watering. When the soil in containers regularly dries out, your vegetable plants put on the brakes. Growth stalls. Or, even worse, your plants skip straight to flowering before they're big enough.

Pin this post!

(When you’re looking for bargain plants at a big-box store and see what looks like a bonsai cauliflower plant that’s only six inches tall, chances are that the plant got parched too often…and that stress made it flower before its time.)

If the potting soil is consistently moist, your crop will be miles ahead. It makes a big difference.

You can keep the potting mix consistently moist with what’s called “sub-irrigated” pots. This is just a fancy way of saying a container with a reservoir. As the potting mix begins to dry, water from the reservoir wicks upwards, keeping the soil continuously moist.

This sort of container is widely available—but you can easily make your own.

Find out more about sub-irrigated (a.k.a. self-watering) pots.

More Container Ideas

If space is tight, small containers might be your only option. I've made herb container gardens by dotting potted plants on a staircase.

Don't forget window boxes. Although they're shallow, they work well for shallow-rooted crops such as leafy greens.

Hanging baskets are a great way to fit more vegetable plants into your container garden.

Find This Helpful?

If we’ve helped in your container-gardening journey, we’re always glad of support. You can high-five us below! Any amount welcome!

Guide: Growing Raspberries (high yield, NO fuss fruit)

This article explains how to plant and care for raspberries in a home garden.

How to Grow Raspberry Plants

At the back of my aunt and uncle's house was a berm made of heavy yellow sticky clay. It was the soil excavated from an addition to their house. The contractor just dumped soil and rubble at the back of their yard.

And it became their raspberry patch.

Raspberries are well suited to the home garden because they’ll thrive in imperfect conditions like that hard-packed berm.

A home gardener can take a very systematic approach to raspberry care…or a hands off approach. Both work with raspberries. (Though by investing some time, you increase the harvest.)

If you want to find out how to grow raspberries, get ideas for using them in the landscape, and find out top tips for raspberry care, keep reading. This post tells you how.

Primer for Growing Raspberries

Let’s start with some raspberry basics.

How Raspberries Grow

A raspberry plant has perennial roots, but the canes live for only two years.

Raspberry bushes have perennial roots (meaning it lives for many years) but the tops—called the “canes”—live for only two seasons.

First-year canes are called “primocanes.” They start out green and tender, and get brown and woody as the season progresses.

Second-year canes are called “floricanes.” Floricanes flower and produce fruit, and then die at the end of the season.

Raspberries that produce fruit on the floricanes are called summer-bearing raspberries or summer-fruiting raspberries.

But some varieties of red and yellow raspberries grow a later crop of fruit on primocanes. These are called everbearing raspberries, fall-bearing raspberries, autumn-fruiting raspberries, or primocane raspberries.

Raspberry Fruiting

Raspberries are late to flower, so flowers are not likely to be hit by late frosts.

You don’t need multiple varieties to get fruit because raspberries are self-fertile. You will get fruit even if you have only one plant.

Here’s when raspberry fruit ripens:

Fruit on floricane-fruiting varieties ripens early summer through to midsummer.

Fruit on fall-bearing varieties ripens mid to late summer. If winter is slow to arrive, you can harvest raspberries until there’s a heavy frost.

Raspberry Growth by Fruit Colour

Yellow raspberries are the same species are red raspberries.

There are red, yellow, black, and purple raspberries. The red raspberries and yellow raspberries are the same species. Black raspberries are a different species. And purple raspberries are a hybrid of red and black.

Red and Yellow Raspberries

Red raspberry and yellow raspberry plants send up new canes from the base of existing canes. New canes also grow from the roots. That means that they don’t remain in a clump, and plants spread out in all directions.

Black and Purple Raspberries

These grow in a tidy clump, with new shoots growing from the base of the clump.

Where to Plant Raspberries

Black raspberries.

If you want to grow raspberries by the book, look for full sun and a rich, well-drained soil.

But in a home garden setting, we don’t always have the ideal conditions that a market gardener might have.

You don’t have to give raspberries the prime real estate.