Raspberry-Leaf Tea and other uses of the Genus Rubus

It’s an astringent. And it might already be growing in your yard or nearby. Today we take you beyond eating raspberry fruit to explore the herbal and medicinal properties of the plant itself—along with its relatives in the genus Rubus. Ever heard of raspberry-leaf tea? Tune in, and find out about the many uses of this plant.

Conrad Richter from Richters Herbs talks about the genus Rubus and its medicinal and herbal uses, such as raspberry-leaf tea.

It’s an astringent. And it might already be growing in your yard or nearby. Today we take you beyond eating raspberry fruit to explore the herbal and medicinal properties of the plant itself—along with its relatives in the genus Rubus.

Ever heard of raspberry-leaf tea? Tune in, and find out about the many uses of this plant.

Raspberry Family

Conrad Richter from Richters Herbs joins us to delve into the history, herbal, and medicinal properties of the approximately 700 species of the genus Rubus.

Science meets History

Richter, who trained in botany, also has a keen interest in history. “I do straddle those two worlds very well,” he says.

He says that the earliest recorded use of Rubus dates back 10,000 years. And 2,000 years ago, the ancient Greeks recorded its use for treating diarrhoea. As an “astringent,” a class of herbs that shrinks tissue, it’s medicinal properties were well documented.

Fast forward to the present day, and Richter says that there is interest in using Rubus leaves in creams to “tonify” the skin, and in the health benefits of the anthocyanins in the fruit.

Cultivate a Taste for Bitter Foods...and Cardoon Plants

Toronto chef and author Jennifer McLagan talks about how to cook bitter foods such as cardoon plants. Photo by Shane Reid.

Chef and author Jennifer McLagan joins us to talk about bitter foods, explaining what bitterness is, and how to effectively use bitter in the kitchen.

McLagan is the author of the book, Bitter: A Taste of the World’s most Dangerous Flavor, with Recipes.

The Loss of Bitter

McLagan recalls the grapefruit that her mother served her as a child. They had a slight bitterness—an “edge.” Her mother balanced that bitterness with a sprinkle of sugar on top.

McLagan says bitterness has been bred out of modern grapefruit. Now they’re sweet and pink…with no bitterness.

That loss inspired her book. “They don’t taste like grapefruit any more,” she says.

What is Bitter?

McLagan says that many people confuse bitter with sour. It is different from sour—one of the four basic tastes, along with sour, sweet, and salty.

“It adds a complexity and depth to the food,” says McLagan, explaining that using bitterness—like salt—makes food more interesting and less flat.

Cardoon plants are one of the bitter foods in Jennifer McLagan’s book, Bitter

She gives the example of crème brulée: The caramel topping has a bitter edge, which plays well with the sweet, rich pudding below.

Cooking with Bitter Foods

McLagan says that bitter is not as popular in North American cuisine as it is in other parts of the world. “The American palate is very geared towards sweet,” she explains.

Bitter pairs well with fat and with sweetness. “Bitter and fat are the two perfect things; one rounds out the other,” she says.

Here are ideas for using bitter in the kitchen:

McLagan talks about making turnip ice cream. She also suggests caramelizing turnips, which go well with baked apple or apple pie.

McLagan suggests cooking Belgian endive in butter (because fat and bitterness work well together) and then using that juice to make béchamel sauce, with added emmenthal cheese, to serve over top of the Belgian endives.

She has surprises in her book! There is a pannacotta with tobacco. McLagan says that small pieces of cigar give it a complex taste. A pannacotta is rich and creamy, and the bitterness from the tobacco comes through very gently at the back of the throat, making it a much more complex dish.

How to Cook Cardoon

For those who have never seen cardoon, McLagan describes it as “celery on steroids.” It has big, wide ribs. And it’s in the cover photo of her book.

The part of the plant that is eaten is the leaf rib. The rest of the leaf is discarded.

She describes it as having an artichoke-and-mushroom flavour—one that will seduce you once you appreciate the bitterness.

Here are McLagan’s tips for preparing and cooking cardoon:

Cut the cardoon stalks from the base.

Remove the spikes along the edge of the rib using a knife.

Next, remove the strings from the stalk (it’s like pulling the strings from a celery stalk).

McLagan finds a sharp knife works better than a vegetable peeler because there are a lot of strings and a peeler plugs up.

Once the stalks are prepared and you begin to chop them, you might find additional strings. If so, remove them.

Once chopped, place them immediately into water with lemon juice to prevent them from browning.

Cook in salted water until tender (the salt is important because salt helps pull out bitterness).

Drain.

Remove any remaining strings.

She says a great way to serve cardoon is with a cheese sauce. “When you put cheese on something, people love it,” she says.

MgLagan notes that the inner stalks are milder, with a better texture. They are less stringy, with a delicate silver-green colour and feathery leaves. She advises using stringy outside stalks for soup; and the more tender inside ones for a gratin or salad.

Here are the cardoon recipes she includes in the book:

Cardoon gratin

Cardoon soup

Warm cardoon and potato salad

Cardoon beef tagine

Cardoon cheese

Cardoon and bitter-leaf salad

Cardoon with braised bitter greens,

My daughter Emma with a cardoon flower. The plants have great ornamental value too.

Bitter in the Garden

One of the challenges—and delights—of growing new food crops in the garden is figuring out how to use them in the kitchen. Looking to add bitter to your garden? Here are ideas:

Arugula

Belgian endive

Cardoon

Citrus rind

Olives

Radicchio

Turnip

Tasty Tomatoes for Small Spaces: The Dwarf Tomato Breeding Project

We’re joined by tomato expert Craig LeHoullier to talk about the Dwarf Tomato Breeding Project, preserving seed varieties, and to find out what’s new in his garden.

LeHoullier, an avid seed saver with a passion for saving and sharing heirloom tomato varieties, says that his seed collection contains somewhere between 50,000 and 70,000 seed packets.

Dwarf Tomato Breeding Project

The project began in 2004. LeHoullier was getting a lot of questions about compact varieties at his annual tomato-plant sale.

He explains that dwarf tomato varieties, which grow vertically at approximately half the rate of other indeterminate tomato varieties, already existed at the time. But these dwarf varieties were obscure and hard to find.

He teamed up with a friend in Australia to start breeding new dwarf tomato varieties. That initiative soon grew into an open source, volunteer-run, worldwide breeding project. The goal was to breed stable, open-pollinated, dwarf tomato varieties from which gardeners could save their own seed.

The project began releasing dwarf tomato varieties to seed companies in 2010.

By 2020, 135 varieties had been released. And the project continues!

Farming Cold-Hardy Citrus in South Carolina

The Johnny Appleseed of cold-hardy citrus, Stan McKenzie, joins us to talk about how to grow citrus in cold climates.

McKenzie talks about how he became a "citraholic" and started down the path of growing citrus on his USDA Zone 8 farm and nursery in South Carolina.

McKenzie Farms specializes in citrus suited for cold climates.

McKenzie says that he coined the term “citraholic” to describe people with a citrus-growing obsession. “It’s not really expensive, and the hangover isn’t nearly as bad,” he says with a laugh.

Getting Started in Cold-Hardy Citrus

He recalls his parents taking him to visit his grandmother when he was a child. Near her house was a scraggly tree that died back to the ground every winter. When he learned it was an orange tree, he was fascinated, and asked his dad to order citrus trees from Florida for their farm.

“Every one of them was killed the very first winter,” he says, explaining that he and his father didn’t know how to overwinter citrus.

Fast forward many years, while visiting Charleston, South Carolina, McKenzie saw a grapefruit tree loaded with golden grapefruit. “It lit the match again,” he says.

As he researched cold-hardy citrus he learned that satsuma trees are grown commercially in colder parts of Japan. It wasn’t long before he started growing satsuma. As his satsuma tree grew and prospered, everybody who saw the tree wanted one.

“That put me in the citrus business,” he says.

Cold-Hardy Citrus Tips

Overwintering Citrus Outdoors

McKenzie says that when overwintering in-ground citrus plants in borderline areas such as his, some citrus enthusiasts wrap the tree in a string of incandescent lights and then cover it with and insulating material. The lights give off enough heat to get the citrus plant through especially cold weather.

Another technique is “micromisting,” where a fine mist of water is sprayed over the trees. As the water freezes, it gives off heat—enough heat for the citrus plants to survive cold weather.

Overwintering Citrus Indoors

Where winter temperatures are more severe, people often bring potted citrus plants into the house over the winter. McKenzie says that the biggest challenge with this technique is that the air in most homes is too dry, causing the plants to drop leaves. The well-known Meyer lemon is especially finicky, he says. However, leaves will grow back in spring.

To maintain a higher humidity that is better suited to citrus plants, he recommends filling a tray (such as the foil trays sold for roasting turkeys) with pebbles and water. He says that spritzing with water regularly helps too.

Top Questions

Thorny growth at the base of the plant. McKenzie explains that many citrus are grafted onto a rootstock of trifoliate orange—a very thorny plant. Sometimes that root will send up a shoot, which, if left to grow, it will overtake the desired variety grafted onto it.

Wrinkled leaves and squiggly lines. He says that this is caused by an insect pest called the citrus leaf miner, which tunnels inside the leaf. While unsightly, they do no harm to the plant and do not affect the fruit.

Common Cold-Hardy Citrus

Prague Satsuma. This hardy satsuma survived the 8°F (-13°C) weater that killed many of the other satsuma varieties in his orchard.

Thomasville Citrangequat. McKenzie says that this cold-hardy citrus is a good lime substitute.

Crosses with trifoliate orange. He says there are many crosses with trifoliate orange that have excellent cold hardiness, but the fruit is usually bitter.

Yuzu, aka Japanese lemon, is very cold-hardy. He knows of people growing this citrus in colder areas such as Raleigh, North Carolina.

Poncirus Trifoliata (a.k.a. Trifoliate Orange)

The trifoliate orange, also known as trifoliate lemon and Poncirus, is extremely hardy, surviving in areas colder than USDA Zone 7. It is a common rootstock. McKenzie says that the small fruit are very seedy and bitter.

Connect with Stan McKenzie

Website: mckenzie-farms.com

Facebook: McKenzie-Farms-Nursery-174405135904728

Find Out How to Grow Your Own Lemons

Grow Lemons in Cold Climates Masterclass shows you how to grow a lemon tree in a pot or outside with protection. And get lemons!

Looking for More Citrus Information?

Plant Partners: Science-Based Companion Planting

Jessica Walliser, author of Plant Partners: Science-Based Companion Planting Strategies for the Vegetable Garden

We’re joined by Pittsburgh-based horticulturist and author Jessica Walliser to talk about her new book Plant Partners: Science-Based Companion Planting Strategies for the Vegetable Garden.

There is a lot of folklore that finds its way into discussions about companion planting. Walliser explains that her hope is to reboot the term “companion planting” by looking at it through a scientific lens.

What is Companion Planting?

Walliser says that companion planting is purposely planting two or more plants close together to get some sort of benefit.

Companion planting does not have to mean putting two plants together at the same time, however; it can also mean growing plants in succession.

Common terms used in science that overlap with the idea of companion planting are:

Intercropping

Plant partners

Interplanting

Polyculture

Benefits of Plant Partners

In her book, Walliser has chapters on seven different benefits of using plant partners in the vegetable garden.

Soil preparation and conditioning

Weed management

Support and structure

Pest management

Disease management

Biological Control

Pollination

An example of pest management is using “trap crops” to lure pests away from other crops. Squash bugs prefer blue hubbard squash to other squash varieties—meaning it can be used as a “trap crop.”

A plant partnership that helps to control aphid problems on lettuce is to grow sweet alyssum as a partner. The alyssum flowers are a favourite of both predatory and parasitic insects that help to control aphids.

For weed management, there are cover crops that suppress growth of weed seeds the following season. Those same cover crops also build soil structure as they decompose.

Living trellises are functional and can be aesthetically pleasing. A good example is using corn with beans.

Ever Heard of “Biodrilling”

An example of a plant partnership to help prepare the soil is the use of deep-rooted forage radishes as “biodrills” on heavy clay soil.

These plants have long tap roots that penetrate heavy soil. The roots are left in the soil to decompose instead of harvesting them. Walliser explains that it’s like using a living drill instead of tilling the soil!

From Market Farming to Italian Seeds

Will Nagengast and Lynn Byczynski, talk about their family business Seeds from Italy, food, and market farming

We head to Kansas to speak with Lynn Byczynski and Will Nagengast about market farming, cut flowers, farm journalism, Italian culinary traditions, and seeds. Their family business is Seeds from Italy.

Byczynski founded Growing for Market, a magazine for market farmers. She is the author of Market Farming Success, The Flower Farmer: An Organic Grower’s Guide to Raising and Selling Cut Flowers, The Hoophouse Handbook.

The Journey into the Seed Business

Byczynski says that when the farm wasn’t enough to support the family, she branched out into producing Growing for Market using her background in journalism and newspaper reporting.

She found that the writing and farming fed off of each other: While interviewing people for articles, she heard ideas that they could try on their farm; and things they were doing on their own farm could be shared with other farmers in Growing for Market.

Seeds from Italy

She says the hair on the back of her neck stood up when an advertiser for her Growing for Market newsletter told her that the sale of his Italian seed distribution business had fallen through. “I could just feel this was the next thing we were going to do,” she says.

The first thing that the family did after taking over Seeds from Italy was to take a trip to Italy to meet the owners of Franchi Seeds, the company whose seed they would be distributing in the United States.

Nagengast and Byczynski say that once home, they immersed themselves in the varieties they were selling by having weekly Italian-themed meals cooked with the Italian varieties they distribute.

Italian Seeds in North America

Italy has a varied climate, with many regional vegetable varieties. They list 23 varieties of zucchini! Most of these different varieties, they explain, are regional varieties.

For North American gardeners thinking about what Italian varieties are best suited to their gardens, they recommend looking to areas of Italy with a similar latitude.

Angelo's Fig Tree

In the Biggs-on-Figs segment for December 2020, we head to the Toronto suburb of Vaughan to get the scoop on the fig tree at Angelo’s Garden Centre.

Over the years Steven has had lots of people ask whether he knows of the tree. He sure does—he’s long admired it.

He finds out about the history of the 19-foot-high fig tree from Carlo Amendolia, owner of Angelo’s Garden Centre.

Grow Herbs in Containers

Herbs in Pots

In a broadcast that originally aired live on The Food Garden Life Radio Show, we chat with herb expert Sue Goetz about growing herbs in containers.

Goetz is an award-winning garden designer, writer, and speaker. Her motto is “Inspiring gardeners to create.” She gives us creative ideas for growing herbs in containers and for using herbs.

Goetz also shares ideas from her new book, Container Herb Garden Complete: Design and Grow Beautiful, Bountiful Herb-Filled Pots.

She is also the author of The Herb Lover’s Spa Book and A Taste for Herbs.

Emma’s Tomato-Talk Segment

In Emma’s tomato segment, we talk about some of Emma’s top tomato-variety recommendations for 2021.

Biggs-on-Figs Segment

In the Biggs-on-Figs segment, we head to the Toronto suburb of Vaughan to get the scoop on the fig tree at Angelo’s Garden Centre.

Over the years Steven has had lots of people ask whether he knows of the tree. He sure does—he’s long admired it.

He finds out about the history of the 19-foot-high fig tree from Carlo Amendolia, owner of Angelo’s Garden Centre.

Pictures of Angelo’s Fig Tree

Using Small Edible Landscapes to Make Big Change

We speak with author, educator, and edible-ecosystem designer Zach Loeks from Eastern Ontario.

A former market gardener, Loeks has converted his farm into the production of berries, fruit, and edible perennials.

He is also the director of the Ecosystem Solution Institute, which is involved in education projects such as an edible-biodiversity conservation area near Ottawa, Ontario. The site includes herbs, fruit trees, berry bushes, and ground covers, all labelled with interpretive signs.

He believes that many small actions can add up to big change. In his new book, The Edible Ecosystem Solution, he talks about ways to grow edibles, even in small spaces.

Starting Small

Loeks says, “I really believe in the power of the micro-landscape.”

For people interested in incorporating edible plants into a landscape, but unsure where to begin, Loeks shares a couple of tips:

Design around the lines on the property: Build out from lines such as fence lines, where sidewalk meets the yard, and the edge of the house.

Connect the dots: Connect the dots between existing ornamental trees instead of starting from scratch. Plant shrubs and herbs beneath the trees. It can be practical too: rather than having to cut the lawn around a tree, it’s easier to cut along the edge of a bed of edibles.

Beautifully Promiscuous and Tasty Tomato Project

We speak with farmer and plant breeder Joseph Lofthouse in northern Utah about breeding tomatoes, and his work with The Beautifully Promiscuous and Tasty Tomato Project.

Lofthouse focuses on breeding landrace crop varieties that are are locally adapted and genetically diverse.

Living in a mountain valley with cold nights and only gets 100 frost-free days, his work breeding tomatoes started out with the simple goal of breeding varieties suited to his growing conditions. “If I wanted to grow tomatoes, I basically had to breed my own tomatoes,” he explains.

He has found much more than cold tolerance.

The Beautifully Promiscuous and Tasty Tomato Project

Lofthouse explains that when tomatoes were domesticated, most of the genetic diversity was lost. So his breeding work has focused on reintroducing wild tomato genetics, with the hope of finding desirable traits not found in domesticated tomatoes.

Along with cold tolerance, the his tomato breeding has produced tomatoes with novel flavours. He says that tropical flavours such as citrus, guava, and mango are appearing. So, too, are other flavours, including smokiness and umami. One chef described the taste of one of the tomatoes as resembling sea-urchin.

While domesticated tomatoes mainly self-pollinate, wild tomatoes, he explains outcross. They readily cross with each other. Hence the use of the word promiscuous in the project name.

Other traits he has encountered in the trials include:

Shrubby growth — something he thinks could offer interesting harvest opportunities

Dense foliage, which could be useful in shading the ground below to minimize week competition

Sprawling growth like a squash plant

Canadian Garden Zones vs. US Garden Zones

Helen Battersby of torontogardens.com

We are joined by Helen Battersby, a Toronto garden blogger, garden coach, and publisher of the Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal.

She explores a topic that a lot of new gardeners are not even aware of—that there are different garden-zone systems used in Canada and the USA.

Always eager to push zone boundaries, Battersby finds that many gardeners live in a state of “zone denial.”

Garden Zones

Battersby talks about the difference between the Canadian and American garden zone systems—both of which provide gardeners with a zone number to use when selecting hardy plant material. The lower the number, the colder the garden zone.

She points out that while her garden is a zone 6 using the Canadian system, it’s a zone 5 using the American system.

The Canadian system uses a number of variables including lowest mean temperature of the coldest month, highest mean temperature of the hottest month, precipitation, and the number of frost-free days.

The American (U.S. Department of Agriculture, or USDA) zones are based solely on average annual minimum temperatures.

She likens the Canadian system to a Betamax; and the US systmem to the VHS.

TorontoGardens.com

Battersby and her sister, Sarah, run the award-winning blog torontogardens.com.

They started the blog at a time when a lot of Canadian gardening magazines were folding, with a goal of filling the gap left by the loss of the gardening magazines.

The Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal

The journal, in its 29th year, was started by Margaret Bennet-Alder. She entrusted the publication of the journal to the Battersby sisters when she was 90.

The journal was born out of tragedy. Bennet-Alder’s son David was diagnosed with schizophrenia. To track his medications and appointments, he created a booklet that had a pair of pages for each week. She saw his book with its seven weekdays, along with an empty eighth space. She decided to use that empty space for garden tasks. And so was planted the seed for The Toronto Gardener’s Journal.

Her son helped her refine the design and taught her how to use software for the creation of the first print run of 500. It became a meaningful project for the both of them.

Growing Perennial Vegetables

We chat with Ben Caesar about perennial vegetables and salad greens. Caesar, who runs Fiddlehead Nursery, specializes in perennial edibles.

He says that in Western cultures, annual vegetable crops are the norm. But with a shift in thinking, it’s easy to incorporate perennial vegetables into the diet.

That shift to perennial vegetables is good because not only can they be easier for gardeners to manage—they require less soil tilling, which means less release of carbon that’s locked up in the soil.

Top Perennial Edibles from Caesar’s Garden in 2020

Seedless sorrel is his all-time favourite this year, a very productive green that he recommends as a “bombproof groundcover”

Caucasian spinach is a little-known vine with excellent ornamental properties

Cutleaf coneflower is a native perennial that produces edible greens in the spring, and 6’ tall flowers in summer

Oxeye daisy, a common roadside weed in Ontario, is a European perennial that has naturalized, with leaves that he says are delicious

Patience dock has leaves that can grow up to 2’ long, but he says to use them when about 1’ long, fresh, cooked—or as a wrap as is often done with grape leaves

Garlic chives are often grown as ornamentals…and he suggests eating leaves and flowers

Bronze fennel has greens with a sweet, anise flavour, and seeds that can be eaten as a palate cleanser and used in pickles

Honewort is a shade-loving native perennial with leaves that Caesar says are delicious

Tips to get Started with Perennial Vegetables

Caesar says that if you already have a perennial garden, chances are that you might already be growing edible plants. Here are common edible plants that he says many people already have in their gardens:

Hosta

Solomon’s seal

Daylily

Stonecrop sedum

Creating New Tomato Varieties

Tomato expert Linda Crago with Emma at a seed exchange.

Tomato expert Linda Crago joins us to talk about how to create a new tomato variety.

At her Tree and Twig Heirloom Vegetable Farm in the Niagara Region of Ontario, she raises hundreds of varieties of tomatoes.

This past summer, Emma grew a couple of tomato varieties that Crago released. She tells us what she did to get them—and shares tips on creating new tomato varieties.

Accidental Crosses

“One was an accidental cross and I was delighted to see it,” says Crago as she talks about ‘TT Baby Blue.’

‘TT Baby Blue’ appeared on its own, from a tomato plant that self-seeded in one of her fields. She thinks that it’s a cross between a blue tomato and one of the currant-type tomatoes.

Crago says that she saved seeds from it and grew the seeds the following year, keeping seeds only from tomatoes that resembled the parent. She did this for six years, which she says is often how long it will take before a new variety becomes “stable.”

De-hybridizing a Hybrid Tomato

Crago says that a lot of people don’t save seeds from hybrid tomatoes because there is no knowing what those seeds will grow into. “You might get somethign you like,” she says.

A few years ago she saw a very interesting tomato at her local grocery store. She bought is so that she could save seeds from it. Those seeds gave her quite a great variety of plants. “I got multiple varieties; not many looked like the original tomato,” she says.

But one of those plants had tomatoes with a peanut-like shape that caught her eye. She grew and selected for that peanut shape for a number of years. Once it was stable, she named the variety ‘Zemoltt.’

Backyard Breeding: Cold-adapted Watermelon, Red-Podded Peas, Tomatoes

Colorado gardener and backyard plant breeder Andrew Barney

We speak with Colorado gardener and backyard plant breeder Andrew Barney about his work developing red-podded peas, cold-adapted watermelons, and new tomato varieties.

Connecting with Other Breeders

Barney connects with other plant breeders through seed swaps, social media groups, and online forums.

He says many people who are interested in plant breeding and preserving plant varieties are happy to share plant genetics.

“If people have something exciting they’re willing to share it.”

Approaches to Breeding

With his pea breeding, barney manages the crosses. It means that he spends time pollinating.

There are also breeding approaches that require less effort, such as landrace-style breeding he's using for his watermelons. In this approach, a number of varieties are planted in the same plot, and cross-pollination is left up to pollinating insects. The job of the breeder is then to select which resulting melons are worth saving seeds from to grow the following year. He’s been working on his melons now for about 10 years.

He’s also involved in The Big Wild Tomato Breeding Project, which he explains is introducing wild tomato genetics. The results, he says, are encouraging, with some participants reporting tomatoes with new flavour profiles that are described as being similar to mango and pineapple.

Top Tip

His advice to would-be backyard plant breeders is, "Just try it!"

Downtown Rooftop Edible Garden Gives a Breath of Fresh Air

Saskia Vegter, Urban Agricultural Co-ordinator at 401 Richmond

We’re joined by Saskia Vegter, the Urban Agricultural Co-Ordinator at 401 Richmond, a former industrial building that has been transformed into a cultural hub in a dense downtown Toronto neighbourhood.

Vegter, who previously worked in event management, felt drawn to work in horticulture.

"I just remembered the feeling of connection when my hands were in the soil.”

401 Richmond

401 Richmond is a former industrial building, built in 1899. Vegter explains that the currant owner restored the building to transform it into a cultural hub for artists and creative entrepreneurs.

Tenants currently include art galleries, a book publisher, a film festival, artists with studios, and a daycare.

The Rooftop Gardens

401 Richmond rooftop garden

The rooftop has three garden areas:

A deck-patio area, which includes trees and shrubs in containers

An extensive sedum green roof

The “mini farm,” which has fruit, vegetables, herbs, and flowers for cutting growing in containers

Tenants use the rooftop for meetings, lunches, to meditate—or just to get a breath of fresh air, says Vegter.

Children from the daycare often spend time on the rooftop, which provides the opportunity for activities such as herb tasting.

Rooftop Crops

Ultra-dwarf apple trees grow in the same containers as the chums (cherry-plums), with strawberry plants at the base

Luffa grows up the pergola

Planters with edibles are planned for edibility AND colour, using plants with ornamental properties

New to the garden this year is a fig tree

Wildlife on the Rooftop

Despite being on a rooftop in a downtown neighbourhood, Vegter says that there are lots of visitors. She laughs as she talks about the squirrel that left her gifts of half-eaten tomatoes during the summer.

She says that other wildlife includes swallowtail caterpillars, hummingbirds, honeybees, and ladybugs.

Profitable Small-Scale Farming

Small-scale farming expert JM Fortier joins us to talk about his road to profitable small-scale farming. He’s an innovator who is out to remake agriculture.

Fortier talks about his own farm, Les Jardins de la Grelinette, as well as his work in training a new crop of farmers at a model polyculture farm in Hemmingford, Quebec, Ferme des Quatre-Temps.

He hopes to connect with non-farmers too, so that they can have a window into the world of farming. He’s done that with a television show, and his newest project—a magazine.

Successful Small-Scale Farming

Fortier is quick to point out that a profitable small farm is not an oxymoron. In his book, The Market Gardener, he outlines the steps that he took to earn more than $100,000 from a 1.5-acre market garden. That figure has risen to over $200,000 today.

He notes that a key element to profitable small-scale farming is to manage expenses.

He says successful small-scale farmers share these traits:

Dedication

Entrepreneurial outlook

A strong sense of customer service

Ability to work with numbers and deal with accounting

Rock-Star Farmer

Fortier notes that there was a great response to the recent French-language television series Les Fermiers (The Farmers) which documented work at Ferme des Quatre-Temps.

The farmers, he says, became TV rock stars.

While celebrity is nothing new in culinary circles, he’s happy to see the growing interest in farming. And he’s not surprised, because he feels there’s a hunger for knowledge about food.

He notes that 95 per cent of the farmers-in-training he’s working with come from a background other than agriculture.

Connecting with Non-Farmers

The Market Gardener has sold more than 200,000 copies and been translated into 7 languages. Fortier says that the book appeals to would-be farmers as well as people who are simply interested in where food comes from.

His next project? A new magazine.

While many print publications are closing up shop, he says that—just like working with the soil—a print magazine is something that’s very tactile.

A return to small: A return to print—they work nicely together.

Getting Ready to Shop for Seeds

Heirloom vegetable grower and tomato expert Linda Crago joins us to talk about seed lingo, saving seeds—and sharing seeds.

An avid seed-saver, she concedes that she has a whole freezer dedicated to seeds alone.

Crago operates Tree and Twig Heirloom Vegetable Farm in the Niagara Region of Ontario. She also organizes an annual Seedy Saturday seed swap and event in her community.

Linda Crago with Emma at a Seedy Saturday

Crazy for Tomatoes

Every spring gardeners from far and wide trek to her farm for her annual Tomato Days sale—where she has transplants for over 500 tomato varieties.

Crago says there’s lots happening in the world of tomatoes—and that in the past 10 years there has been more change since people started growing them to eat.

Seed Lingo

Hybrid: Crago explains that hybrids can occur naturally. While some hybrids are known for disease resistance, hybrid varieties are not the best choice for home gardeners who want to save seed. That’s because seeds from hybrids won’t be like the plant they came from.

Heirloom: She says that heirlooms are varieties with a history and a story. They have been around for a long time; 50 years is a common guideline when calling a variety an heirloom.

Open Pollinated: These are stable varieties that give seeds like the parent plant (as long as they have not cross-pollinated with a nearby plant.) While all heirlooms are open pollinated, not all open-pollinated varieties are heirlooms.

Artisan: These are newer open-pollinated varieties with special taste or unique appearance.

Hybrid Heirlooms: This term is used by some seed companies to refer to hybrids that look like an heirloom. Crago explains that heirlooms are always open pollinated, making this a misleading label.

Crago points to newer open-pollinated varieties such as some of the blue tomatoes…they’re not heirlooms now, but who knows, maybe they will be in 50 years.

Saving Seeds

Crago says that it’s not necessary to buy new seed every year. Seeds for some crops, such as parsnip, do have a shorter life, but she says that with proper storage, it’s usually possible to get more than one year from a batch of seed.

If in doubt, she recommends doing a seed viability test. Simply put seeds in damp paper towel within a sealed bag, in a warm location. After a few days, check to see how many of the seeds have germinated.

“One of the ways we keep open-pollinated varieties in existence is by growing and eating them.”

Seed Exchanges and Seed Libraries

Crago says that the first seed library in Canada was in the nearby Grimsby Public Library.

She says it’s not uncommon to hear stories at seed exchanges: seeds often come with the story of how they were brought from another country by a relative—and the people sharing them are hoping that someone will keep the variety going.

“The stories are the best and the varieties you get are the best.”

Elderberry: Forgotten Fruit Makes a Comeback

In our second chat with Kentucky farmer and author John Moody, we talk about elderberry.

Moody is the author of The Elderberry Book, in which he explores not only the cultivation and use of elderberry, but also it’s rich history.

Long History of Elderberry Use

Moody told his publisher, “I want to write a book about elderberry because it’s been almost 1,400 years since there was a book written about only elderberry.”

With his knowledge of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, Moody has been able to explore its use and lore in ancient texts.

There is a lot of story and lore involving elderberry in more recent times too. He points out that they can be found in Harry Potter, Monty Python, Shakespeare—and are even the subject of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale.

Elderberry on his Farm

Moody says that on his farm, each of his children is required to have a homestead business. His daughter Abby chose elderberry syrup—and the business has done extremely well.

Elderberry is in demand: He says that there is currently not enough elderberry to supply demand in North America.

Using Elderberry

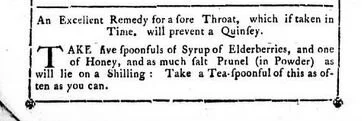

Elderberry recipe from a calendar made in Nova Scotia, Canada in 1793

The elderberry fruit has many uses, including juice, tea, jelly, pie, and marinades.

The flowers can also be consumed, and are frequently used in teas, salads, and fritters.

But Moody says there is a rich history of use of medicinal use of other parts of the elderberry plant.

Top Tips for Growing Elderberry

Moody’s top three tips for growing elderberry:

Grow a number of varieties to determine which will be the most productive in your conditions

The least expensive way to get plants is by rooting hardwood cuttings

Elderberry is a moisture-loving plant, so give it a wet location, for example, near a downspout

From Urban Junk-Food Junkie to Farmer

We chat with Kentucky farm educator and homesteader John Moody to learn how a junk-food-eating city kid ended up as a farmer and farm educator.

Moody, who had been heading towards a career in academia so that he could teach, says that in hindsight, “I got a farm so I can teach.”

Food-Buying Club

After a health scare, Moody and his wife began to change their eating habits, buy more whole foods and locally grown foods.

With the change in food buying habits, he noticed that his food bill went way up. “The farmers aren’t getting any of this money I’m spending,” he thought.

That led Moody and his wife to source food directly from farmers and start a food-buying club, Whole Life Buying Club.

Getting into Farming

His interest in growing food evolved out of his interest in healthy food—especially after meeting farmers who were sceptical about cutting their use of external inputs.

So he set out to do it himself.

“I bought a farm, soil not included,” says Moody as he talks about building soil from scratch on a degraded piece of land.

An Outsider’s Perspective

Moody talks about how, on a small farm such as theirs, 30 bottles of specialty elderberry syrup brings in roughly the same amount as what a conventional farmer might get from an acre of corn.

Growing Nuts in Cooler Climates

In this interview that first broadcast live on the Food Garden Life Radio Show in 2018, we chat with nut-growing expert Ernie Grimo from Grimo Nut Nursery in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario.

Nut expert Ernie Grimo

When Grimo set out to grow nuts in his yard, he couldn’t find local nurseries selling plants.

That was the beginning of his foray into collecting, breeding, and selling nut trees.

“When I had 100 trees in my backyard, it was time to find somewhere else to put them,” he says.

Cold-Adapted Nuts

At his farm and nursery in Niagara, Grimo grows a wide variety of cold-adapted nuts including:

heartnut

butternut

Persian walnut

black walnut

pine nut

hazelnut

chestnut

beech

hickory

pecan

He also has crosses such as the “hican,” a hickory-pecan cross.

Hazelnut Industry in Ontario

Grimo talks about the potential for a hazelnut industry in Ontario, noting that some people talk about the potential to have 40,000 acres in production.