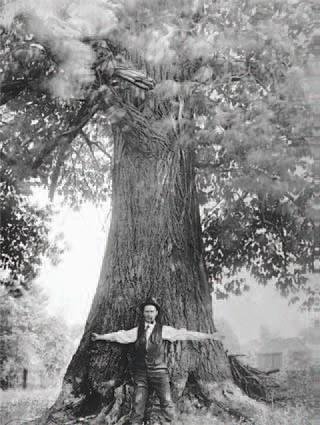

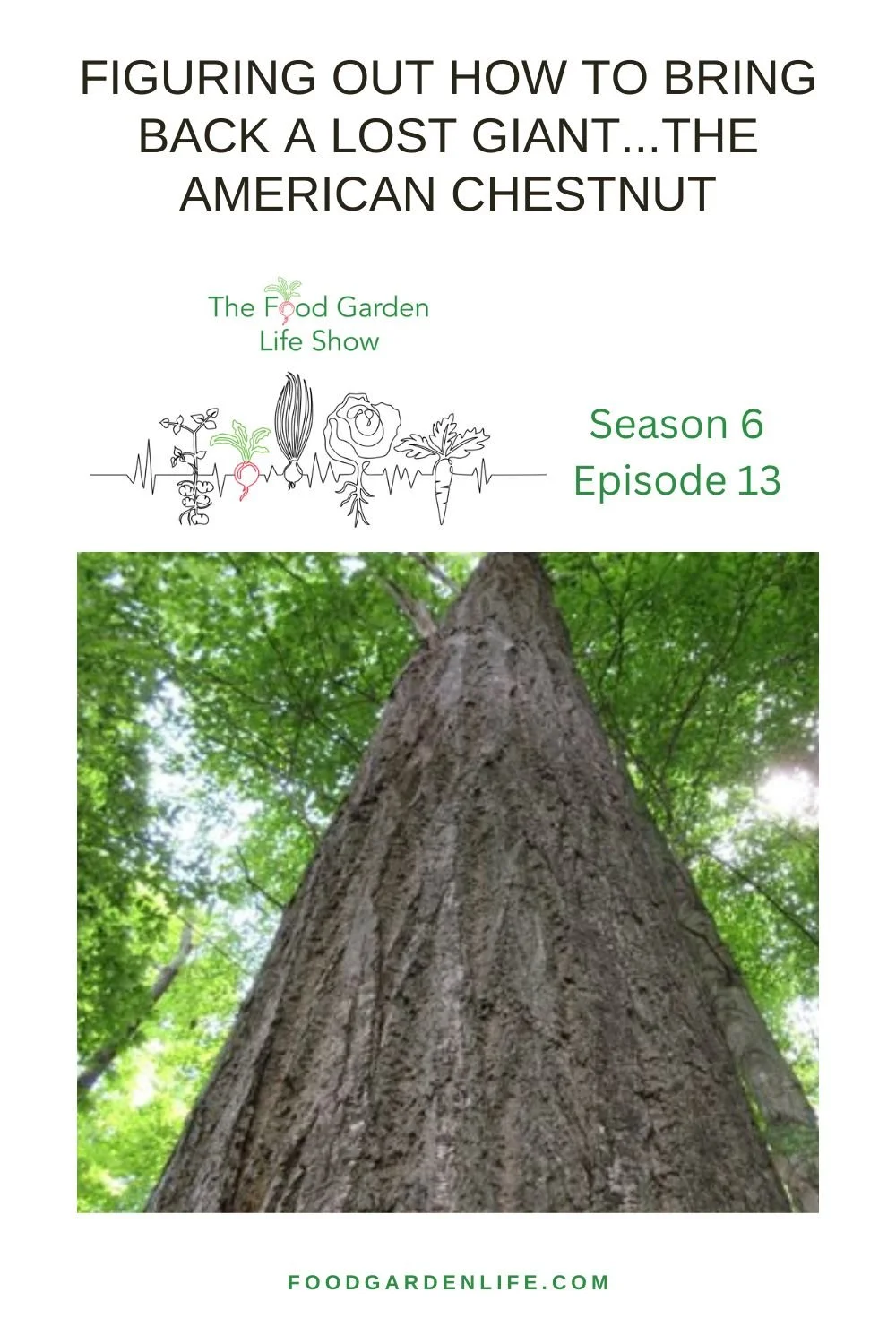

Figuring Out How to Bring Back a Lost Giant...the American Chestnut

Talking about the American chestnut and breeding disease-resistant varieties with Ron Casier from the Canadian Chestnut Council.

Blight-Resistant American Chestnut in Canada

In this episode, we dig into some history, a sad story – and hope.

All this from a tree that was known as the redwood of the east. A towering tree prized for its wood. A tree pivotal to the forest ecosystem.

And by the 1950s, it was thought to be extinct in Ontario.

But it wasn’t extinct. And it’s not extinct now.

We head to southwestern Ontario to find out what the Canadian Chestnut Council is doing to bring the American chestnut back to the landscape.

Whether you’re a forager, interested in food forests, or want to grow nuts, this is a fun chat.

Our chestnut guide is Ron Casier, chair of the Canadian Chestnut Council.

We talk about:

The American chestnut, and the place it held in the ecosystem

Chestnut blight, and its effect on chestnut populations

The “Canadian” American chestnut

Breeding disease-resistance American chestnut varieties

Cold-Hardy Fruit and Nuts, Gardens for Native Pollinators

In this episode: Cold-hardy fruit with Allyson Levy and Scott Serrano and gardening for native pollinators with Sheila Colla and Lorraine Johnson.

Talking about cold-hardy fruits and nuts and native pollinators.

Cold-Hardy Fruit and Nuts

In the first part of the show, we chat with veteran fruit growers Allyson Levy and Scott Serrano, founders of Hortus Arboretum and Botanical Gardens.

Their focus is cold-hardy fruit and nuts with good disease resistance and minimal pest problems — plants suited to home gardens and landscapes.

They tell us about:

Medlar

Mulberry

Himalayan Chocolate Berry

Honeyberry (a.k.a. Haskap)

Hazelnut

Their new book is Cold-Hardy Fruits and Nuts: 50 Easy-to-Grow Plants for the Organic Home Garden or Landscape.

Creating Habitat for Native Pollinators

In the second part of the show we talk about native bees and how we can support them in our gardens, with bumblebee researcher Sheila Colla and native plant expert Lorraine Johnson.

They tell us about:

Gardening as a way to support native bee species

How honeybees can impact native bee populations

The disappearance of the rusty patched bumblebee in Ontario

Their new book is A Garden for the Rusty-Patched Bumblebee: Creating Habitat for Native Pollinators.

Growing Nuts in Cooler Climates

In this interview that first broadcast live on the Food Garden Life Radio Show in 2018, we chat with nut-growing expert Ernie Grimo from Grimo Nut Nursery in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario.

Nut expert Ernie Grimo

When Grimo set out to grow nuts in his yard, he couldn’t find local nurseries selling plants.

That was the beginning of his foray into collecting, breeding, and selling nut trees.

“When I had 100 trees in my backyard, it was time to find somewhere else to put them,” he says.

Cold-Adapted Nuts

At his farm and nursery in Niagara, Grimo grows a wide variety of cold-adapted nuts including:

heartnut

butternut

Persian walnut

black walnut

pine nut

hazelnut

chestnut

beech

hickory

pecan

He also has crosses such as the “hican,” a hickory-pecan cross.

Hazelnut Industry in Ontario

Grimo talks about the potential for a hazelnut industry in Ontario, noting that some people talk about the potential to have 40,000 acres in production.

Grow a Food Forest

Ryan Cullen, field supervisor at Durham College, talks about the new food forest at Durham College.

Make a Food Forest

We chat with Ryan Cullen, the field supervisor at Durham College, about the newly planted food-forest garden at the college’s Whitby campus.

Cullen oversees a diverse market garden that includes tree fruit, small fruit, cut flowers, field vegetables, greenhouse vegetables, and microgreens. He previously joined us on the show in Aug 2019. Click here to tune in to that episode.

Food-Forest Garden

Cullen explains that the idea behind the food forest is to grow a mix of food-producing species, layered in the same way that a forest is. There’s a herbaceous layer at ground level, a shrub layer, and a canopy layer of trees above.

With time, the food forest becomes self-maintaining and, with the appropriate mix of plant species, can have self-renewing fertility.

The top layer of the food-forest garden is the “canopy” layer. Cullen says that they planted this layer with fruiting tree species including cherries, plums, persimmon—and even a hawthorn.

The lower herbaceous and shrub layers, which are still being developed, will be a polyculture—a mix of different plants. Along with edible properties, plants in the lower layers might make available soil nutrients (deep-rooted plants bring up nutrients,) supply nutrients (pea shrubs capture nitrogen from the air,) and attract pollinator species.

Lower-layer plants include bee balm, chamomile, rosa rugosa (for rose hips), strawberreis, and blueberries. Cullen says that this list will grow, as there is still a lot of planting to do in this layer.

Food and Farming Program

The on-campus market garden is part of Durham College’s Food and Farming program, which focuses on urban and small-scale agriculture.

The program has a field-to-fork philosophy. Located on a former industrial site, the market garden produces a variety of vegetables and fruits to supply the on-campus restaurant, Bistro 67.

In addition to supplying the restaurant, the harvest also goes into a community-shared agriculture program (CSA) and farmers market.