Virtual Apple Tasting

Susan Poizner talks about the virtual apple tasting she recently held to raise money for her community orchard.

Fruit-tree educator Susan Poizner from Orchard People talks about holding a virtual apple-tasting event.

Stop and smell the roses? Community event helps people to stop and smell…apples.

Susan Poizner recently helped 50 Torontonians to stop and smell…apples. Poizner, a fruit-tree-care educator and college instructor with a passion for growing fruit trees, organized a virtual apple-tasting event as a fundraiser for her local community orchard.

Virtual Apple-Tasting Event

Poizner visited an orchard specializing in heirloom apple varieties to get enough apples for 50 participants.

Participants received a paper bag containing the six apple varieties for the tasting. Each was marked with coloured stickers for identification.

To help participants think about what they were tasting, the event was facilitated by an apple sommelier, a researcher specializing in taste perception.

Poizner explains that researchers testing new apple varieties for consumer acceptance might consider upwards of 50 things.

For this event, participants were asked to share feedback on four things:

Overall apple intensity

Honey

Floral

Green-Herbaceous

Want to know more about apple tasting? Check out this Apple Tasting Wheel.

Apple Varieties

The tasting event took attendees to different parts of the world with six heirloom apple varieties.

Kindel Sinap (Turkey)

Cranberry Pippin (New England)

Baxter (Ontario)

Empire (New York)

Melrose (Ohio)

Horneburger Pancake (Germany)

Thinking of holding a tasting event? READ MORE about an apple-tasting event in this article.

Grow Quince and Garden Journal

Nan Stefanik talks about growing quince. Helen Battersby talks about the Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal

Today: Nan Stefanik of Vermont Quince talks about how to grow quince. Helen Battersby talks about the 30th anniversary of a garden journal with a special story.

Grow Quince in Cold Climates

Imagine a job that revolved around a plant you’re passionate about. What plant would it be for you?

For Nan Stefanik that plant is quince.

She first tasted quince as an adult, on an overseas trip. After returning home, she was surprised to learn it grew locally in New England.

With a long history of its cultivation in New England, knowledge of quince had receded over time.

#GrowQuince

Stefanik’s business, Vermont Quince, makes quince paste, quince preserves, and other specialty quince products using New-England-grown quince.

Along with food products, she has made it her mission to collect and share quince information.

Using a specialty-crop grant, she started a #GrowQuince campaign to share quince-growing information.

Find more information about how to grow and how to cook quince on the Vermont Quince website.

What’s next? Stefanik and her son have acquired land for a quince education centre where they can combine a shop, demonstrations, and hold scion exchanges.

A fabric showing the different types of quince used in a recent quince taste test.

Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal

Our second guest today is also passionate about what she does. Helen Battersby produces the Toronto and Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the journal, which includes information about frost dates, seed-starting dates, plant and seed sources — and also has space to record garden successes and failures.

There’s a deeply human story behind the journal, the story of a mother helping a son. Battersby shares that story, and talks about what’s new in the 2022 edition.

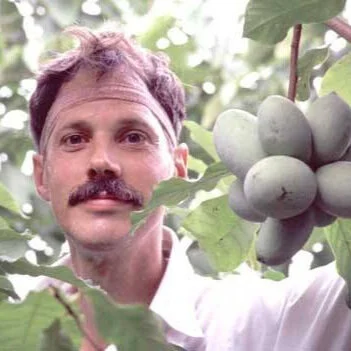

Pawpaw in Ontario with Paul DeCampo

Paul DeCampo talks about growing pawpaw in Ontario.

Paul DeCampo talks about pawpaw in Ontario: its history and how to grow it.

Pawpaw. It’s a fruit that has a long history in Ontario.

Yet it’s not well-known, nor do most people realize it grows wild in some parts of the province.

Paul DeCampo, Toronto’s pawpaw ambassador, planted his first pawpaw trees in 1994. “Nobody I knew had ever heard of this fruit,” he says.

Working in the food industry, he has had the opportunity to share his pawpaw fruit with chefs. Describing how, years later chefs will still talk about a fruit he gave them, he says, “Even if you’re someone who spends all day tasting the most interesting things, these are particularly astounding.”

Why Grow Pawpaw?

Pawpaw fruit from Paul DeCampo’s Toronto garden.

Besides the fact that the fruit is almost never available for sale, DeCampo says a pawpaw tree is a good fit for the challenges of a city yard.

That’s because:

Pawpaw does not require full sun

Pawpaw grows well under black walnut trees (which give off a compound that is toxic to many other plants)

There are very few pests that affect pawpaw

DeCampo’s Pawpaw Tips

DeCampo suggests thinking of a forest-edge garden when planting pawpaw. For urban gardeners, the shade of the forest is replaced by the shade of buildings.

Other tips:

Get three plants (two genetically-distinct plants are needed to get fruit…but nothing is certain in gardening, so DeCampo says to play it safe, and get three)

Life is short, so buy as large a tree as you can find and enjoy the fruit sooner

Pawpaw Resources

Plants: Grimo Nut Nursery

Books:

The Pawpaw Grower’s Manual for Ontario, by Dan Bissonnette

The novel The Overstory, by Richard Powers. The pawpaw is described as, “A sheepdog of trees;” the fruit having flesh that tastes like butterscotch pudding.

A Windy Newfoundland Homestead with a Sustainable Focus

David Goodyear talks about his homestead at Flatrock, Newfoundland.

David Goodyear

Old becomes new.

When David Goodyear began to think about food costs, sustainability, and how he and his family ate, he sat down with older relatives to hear how people used to eat. “Everybody ate root crops because they grew it themselves,” he was told.

Goodyear says there are many root crops that grow well in Newfoundland. It didn’t seem right when his grocery store had carrots from abroad. Nor did it didn’t seem sustainable.

Change in Diet Turns to Growing

Goodyear and his family started by changing their diet and eating more root crops. The food bill went down. They found more locally raised choices.

Then they decided to grow their own root crops.

Today they grow root crops, greens, tomatoes, strawberries…even figs. The next project? A food forest.

As Goodyear explains, his is a challenging climate. His town, Flatrock, is close to St. John’s, the third windiest city in the world. He has 110 frost-free days a year. “Winter starts in November; it doesn’t end till the end of May,” he says.

The focus on growing their own food led to an interest in storing the harvest. “If you’re going to grow a massive amount of root crops you need somewhere to put them,” says Goodyear as he talks about his root cellar.

Goodyear and his family switched up their diet; and have now switched up their life. Their homestead includes the gardens, a root cellar, a greenhouse, and a passive home.

Edible Front Yards and Sensory Gardens

Jennifer Lauruol on edible front yards, sensory gardens, and native plants

Regenerative-garden designer Jennifer Lauruol talks about edible front yards, sensory gardens, and native plants.

Jennifer Lauruol weaves together permaculture concepts, native plants, food plants, forest gardening, and educational elements in her regenerative-garden design work in Lancaster, England.

Her passion is edible ornamental gardening—especially in front yards.

Lauruol also uses many native plants in her designs. She finds that effective design helps people interpret the use of native plants as a garden.

Edible Front Yards

Lauruol recalls a neighbour’s concern that children might steal the fruit that Lauruol was growing in her front yard. Yet that was exactly her goal: that children would enjoy the fruit and learn where it comes from.

She says that a well-planned garden can have a succession of edible fruits and ornamental plants. Another way to weave edible plants into a landscape is to create an edible hedge.

While edible front gardens might not appeal to everyone’s taste, Lauruol does have a tip for gardeners worried about sceptical neighbours: “I do know what to do about the diehards: give them strawberries,” she says.

Native Plants

Lauruol explains that having a mown strip around plantings of native plants helps people understand it as something intentional. “If you create a frame around it then people can understand it,” she says.

Her own design with native plants is strongly influenced by Brazilian artist, painter, and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, who used big blocks of colour in his work. She says planting native plants in large drifts, as opposed to mixed plantings, is an approach that is less likely to be interpreted as sloppy.

Sensory Gardens

Lauruol creates sensory gardens for people with special needs. Her focus on sensory gardens stems from her own experience with her daughter Marie, who has special needs. “She comes alive when she is in nature,” says Lauruol, adding, “For me, the base of a sensory garden really needs to be a wildlife garden.”

Senses to stimulate with a sensory garden:

Sound. The sense of sound is often overlooked in garden design..

Sight. Lauruol likes to make colourful planting in the shape of a rainbow so visitors get a very strong sense of each colour

Taste.

Smell. “Different kinds of scent are like an orchestra,” says Lauruol. She says to remember scents other than floral scents, such as compost with its woody notes.

Touch.

Meet the Indiana Jones of Pawpaw

Neal Peterson hunted down lost pawpaw varieties to use for his pawpaw breeding work

Neal Peterson hunted down lost pawpaw varieties from the early 20th century to use in his pawpaw breeding work.

Meet Neal Peterson, the Indiana Jones of pawpaws. He was so moved by the taste of pawpaw that it became his life’s work.

There were improved pawpaw varieties in the early 20th century—but the fruit fell into obscurity.

Peterson dug through the literature to uncover past pawpaw breeding work, and then set out to track down lost varieties for use in his own pawpaw breeding work.

About Pawpaw

Peterson says that in the wild, pawpaws are an “understorey” tree, often growing in shade of larger forest trees. When they are in shady locations they become lanky and do not produce a lot of fruit.

But given more light, they produce much more fruit.

Two genetically distinct trees are needed to produce fruit.

Pawpaws sucker extensively, which can give rise to groves of pawpaw that are all clones from a single parent tree.

Peterson says that in the wild, pawpaw fruit can be quite seedy, with up to 25% seed by weight. In his work he has bred varieties with more fruit and less seed. His best variety has 4% seed by weight.

Pawpaws at Home

Pawpaw trees are well suited to a home garden, growing to approximately 20 feet high. While orchardists might space trees widely for equipment, home gardeners can reduce spacing.

Grow 2 in the space of 1: Peterson recommends planting two trees only a couple of feet apart if space is a challenge.

Choose a sunny site: While trees are shade-tolerant, they produce more fruit in sunny locations.

Minimize competition: Keep weeds and grass two feet away from the tree until it is well established

Keep soil moist: Mulch with compost to minimize weed growth and keep soil moist.

For cold climates: Choose early-ripening varieties such as ‘Shenandoah’ or ‘Allegheny’

Caution: Weed eaters can damage the bark.

Once established, pawpaw trees sucker profusely. If growing an improved variety that is grafted onto a rootstock, remove the suckers, which will be the same as the rootstock.

Grow Pawpaw from Seed

For gardeners who want to grow pawpaw from seed, Peterson notes that they are slow to germinate.

He suggests planting the seeds in the fall where they are to grow, or storing in the fridge in damp sphagnum moss in a sealed bag. They require a period of cold, moist conditions before germination.

Do not allow seeds to dry out because this will greatly reduce germination.

He says it can take 7 years until seed-grown trees flower.

Grow Fruit in a Small Garden

Christy Wilhelmi talks about how to grow fruit in small spaces

Christy Wilhelmi is a self-described garden nerd with a passion for growing fruit and vegetables, and is an expert at small-space edible garden design.

In a broadcast that originally aired live on The Food Garden Life Radio Show, we head to California to talk with Christy Wilhelmi, a self-described garden nerd with a passion for growing fruit and vegetables, and an expert at small-space edible-garden design.

In the podcast she shares tips about:

Incorporating fruit plants in small-space gardens

Growing fruit in containers

Pruning

Tips to succeed for gardeners who are new to growing fruit

Her obsession with gardening began in 1996 on the balcony of her Los Angeles apartment. That led her to a weekly gardening TV show, serving on the board for a community garden, and writing gardening books.

Wilhelmi is the author of the new book, Grow Your Own Mini Fruit Garden. Her previous books are Gardening for Geeks, and 400+ Tips for Organic Gardening Success.

Grow a Fruit Garden

Wilhelmi’s new book is Grow Your Own Mini Fruit Garden: Planting and Tending Small Fruit Trees and Berries in Gardens and Containers.

In the book she focuses on how to grow more food in less space, and how to turn a garden of any size into a “fruit factory.”

Foodscaping

Jeremy Cooper talks about foodscaping

Jeremy Cooper from Cooper’s Foodscaping talks about his path into foodscaping and shares his top tips.

Today on the podcast we talk about “foodscaping,” gardening that combines the ornamental with the edible, also known as edible landscaping.

Foodscaper Jeremy Cooper says he likes to work with plants that have multiple functions, including ornamental, herbal, medicinal, ecological, and edible.

Cooper worked in a number of jobs before focusing on foodscaping. In hindsight, he sees that he was circling this intersection of food, gardening, and the environmental before he even realized it.

Part of what he does as a foodscaper is to educate clients about smarter ways to garden. For example, many times he’ll find people battling plants that are edible. “That’s food!” he tells them, as he helps them see the plants in another light.

Foodscaping Tips

Cooper’s tips for gardeners interested in foodscaping:

Don’t be afraid to dream about other ways to use a space and think about what you might like in the long term. “Don’t be afraid to dream…it doesn’t have to be a lawn,” he says.

Grow foods you like to eat.

Make sure the soil is healthy, and, if in doubt, dig into the topsoil and then down below the topsoil to see what is there. He points out that in many new subdivisions, gardeners are left with hard-packed soil and gravel beneath a shallow layer of topsoil.

Cooper’s Favourite Food Plants

Serviceberry. Cooper says that while many people grow this as an ornamental plant, a lot of people don’t realize the fruit are edible. He points out that it’s an excellent understory tree that does well in partial sun.

Amaranth. Beautiful, colourful. Edible leaves and grain.

Currants.

Bergamot. Flowers and herbal uses.

Yarrow. Flowers and herbal uses.

Squashes.

Forest Gardens and Fruit

We chat with forest garden designer and edible landscaper Mark Lord about lesser know fruiting plants.

We chat with forest garden designer and edible landscaper Mark Lord in south-western Germany.

“A garden should be a holistic experience, feeding all of your senses, and your mind,” says Lord. He believes food gardens can be about more than just eating—that they can also be visually appealing, bio-diverse, and appeal to other senses such as smell.

We also digress into his experiments making liqueur including linden, serviceberry, cherry…and nettle!

Lord operates The Fruit Nursery, which specializes in unusual and rare plants that produce edible fruit.

Forest Garden Design

Lord talks about the 7 layers that he builds into his forest garden designs.

Upper Tree Layer. This includes taller tree species such as apple, mulberry, and quince.

Lower Tree Layer. This includes shorter trees such as serviceberry.

Vertical Layer. This is a climbing layer with vines such as kiwi, grape—or even vining peas.

Shrub Layer. This includes smaller shrubs such as barberry and currant.

Herb Layer. This layer includes herbaceous plants.

Ground-Cover Layer. This layer can include plants such as creeping bramble.

Underground Layer. This layer includes plants with edible roots, e.g. horseradish.

Lesser Known Fruit

Lord’s passion is unusual and rare plants that produce edible fruit. Here are some of the plants we discuss in the podcast:

Elderberry. In addition to Canada elderberry, he grows blue elderberry (Sambucus caerulea), which he loves for the visual impact of the bright blue fruit.

Serviceberry. He explains that in addition to fruit, serviceberry offers showy white flowers in spring, attractive grey bark in winter—and colourful leaves in the fall.

Haskap. Called “blue honeysuckle” in Europe, he feels this plant deserves space in more gardens for both the fruit and the fall leaf colour.

Clove Currant. This common hedging shrub belongs in edible landscapes too! It has flowers, fragrance, and fruit. “It’s kind of like a black-currant-not-lovers currant,” says Lord.

Cherry Plum. “Cherry plums are fantastic!”

Hardy Kiwi. The vining hardy kiwi is an excellent way to incorporate a vertical layer into a forest garden. He notes that 2 plants are necessary, both a male and female.

Cornelian Cherry. This is Lords favourite. Along with early flowers, this shrub has delicious fruit.

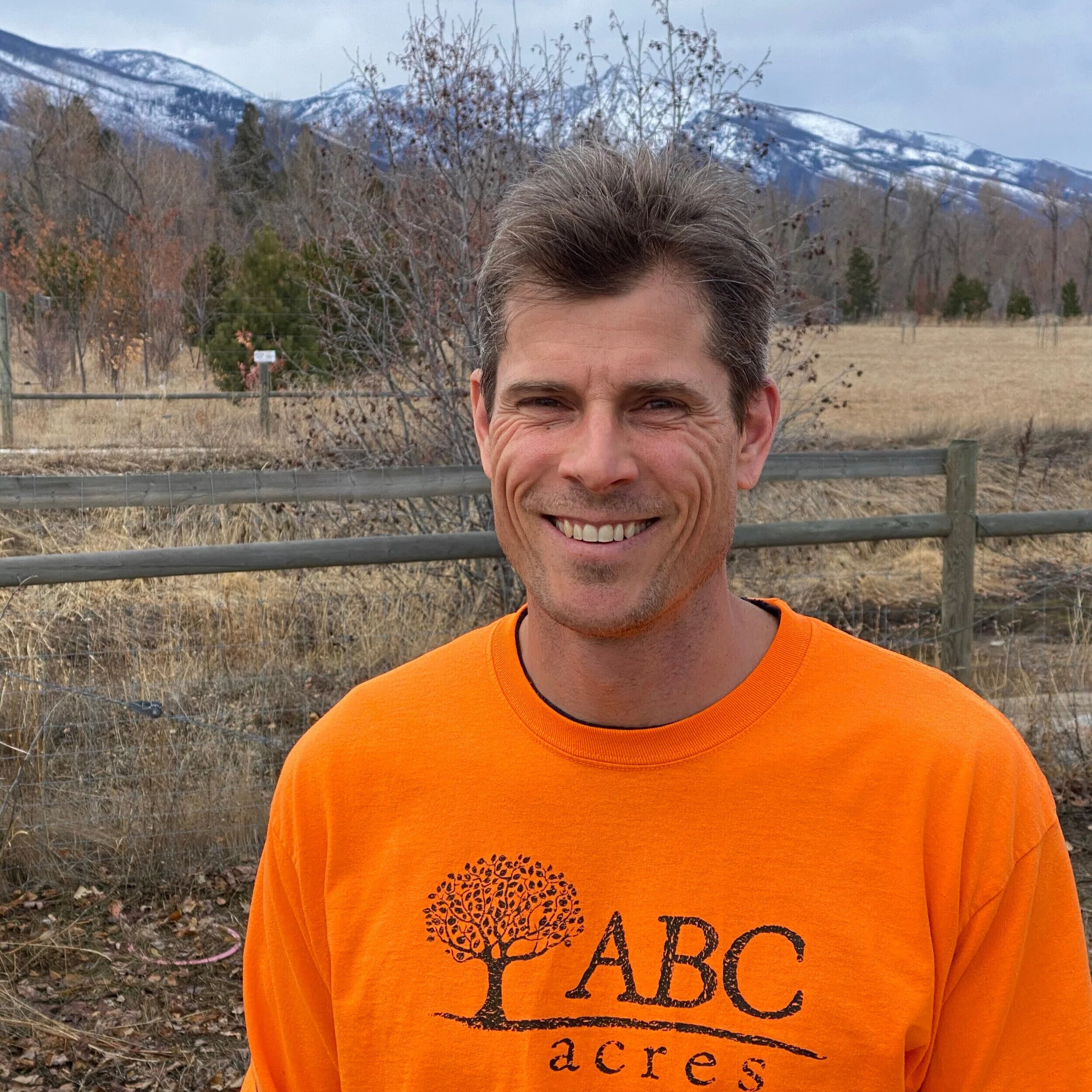

Crater Garden, Regenerative Farm and Family

This permaculture operation has neat features including a crater garden, food hedge, and chinampas.

Tim Southwell of ABC Acres in Montanna talks about a regenerative approach to farming, family, community—and about his crater garden.

“Our chickens know no boundaries.”

We head to Montana to chat with Tim Southwell of ABC Acres, the permaculture homestead he and his his wife Sarah created.

Southwell, who grew up in suburban Houston, explains that it was while living in Kansas City and growing a front-yard vegetable garden that he was introduced to permaculture and many of the concepts that he uses today on the farm.

In addition to livestock, they have a crater garden, a food hedge, chinampas, and a sunken greenhouse with citrus, bananas, figs, and papaya.

The unique microclimate created by the crater garden permits them to grow apples, peaches, plums, nectarines, and apricots in their harsh climate. He explains, “Every fruit tree we have, we build with it a microclimate.”

Crater Garden

Southwell says that the microclimate in the crater garden—a below-grade garden—is created by a number of things that work together:

The winter sun warms the south-facing slope of the garden.

Runoff from rain collects at the bottom of the garden, creating a pond—and the water in the pond collects heat that is then radiated at night.

The water reflects light onto plants in the surrounding crater garden.

Because the garden is below grade, cold winds pass over top of it.

While frost normally settles into low areas, it does not settle into the crater garden because the thermal mass of the water creates convection, so the air keeps moving.

Large rocks are partially submerged in the pond to act as “battery chargers” in the pond, adding to the thermal mass.

Food Hedge

The food hedge, which Southwell calls the “fedge,” provides privacy, blocks wind, attracts birds, and keeps livestock where they are supposed to be. Food plants in the fedge include:

brambles

sand cherry

serviceberry

goji

aronia

josta

honeyberry

“My children will be outside grazing the food hedge.”

Chinampas

Southwell explains that he was inspired by systems used by Aztec famers to create “chinampas” on a boggy section of flood plain.

He placed cottonwood logs on the low-lying ground, and then capped them with old hay and leaves, which decompose to create a rich soil. Over time, the decaying, spongy cottonwood logs help to wick moisture upwards.

He says that in this sort of situation it’s important to grow plants that don’t mind moisture. Raspberries grow well for them.

Agritourism

Agritourism become an income generator on the farm in 2017. Southwell noticed a big appetite for opportunities to connect with farms, food production, and nature.

But he felt that farms, and the stories behind them, were poorly represented online. He and Sarah created the online platform yonder.com as a way for to connect people with nature.

Raspberry-Leaf Tea and other uses of the Genus Rubus

It’s an astringent. And it might already be growing in your yard or nearby. Today we take you beyond eating raspberry fruit to explore the herbal and medicinal properties of the plant itself—along with its relatives in the genus Rubus. Ever heard of raspberry-leaf tea? Tune in, and find out about the many uses of this plant.

Conrad Richter from Richters Herbs talks about the genus Rubus and its medicinal and herbal uses, such as raspberry-leaf tea.

It’s an astringent. And it might already be growing in your yard or nearby. Today we take you beyond eating raspberry fruit to explore the herbal and medicinal properties of the plant itself—along with its relatives in the genus Rubus.

Ever heard of raspberry-leaf tea? Tune in, and find out about the many uses of this plant.

Raspberry Family

Conrad Richter from Richters Herbs joins us to delve into the history, herbal, and medicinal properties of the approximately 700 species of the genus Rubus.

Science meets History

Richter, who trained in botany, also has a keen interest in history. “I do straddle those two worlds very well,” he says.

He says that the earliest recorded use of Rubus dates back 10,000 years. And 2,000 years ago, the ancient Greeks recorded its use for treating diarrhoea. As an “astringent,” a class of herbs that shrinks tissue, it’s medicinal properties were well documented.

Fast forward to the present day, and Richter says that there is interest in using Rubus leaves in creams to “tonify” the skin, and in the health benefits of the anthocyanins in the fruit.

Farming Cold-Hardy Citrus in South Carolina

The Johnny Appleseed of cold-hardy citrus, Stan McKenzie, joins us to talk about how to grow citrus in cold climates.

McKenzie talks about how he became a "citraholic" and started down the path of growing citrus on his USDA Zone 8 farm and nursery in South Carolina.

McKenzie Farms specializes in citrus suited for cold climates.

McKenzie says that he coined the term “citraholic” to describe people with a citrus-growing obsession. “It’s not really expensive, and the hangover isn’t nearly as bad,” he says with a laugh.

Getting Started in Cold-Hardy Citrus

He recalls his parents taking him to visit his grandmother when he was a child. Near her house was a scraggly tree that died back to the ground every winter. When he learned it was an orange tree, he was fascinated, and asked his dad to order citrus trees from Florida for their farm.

“Every one of them was killed the very first winter,” he says, explaining that he and his father didn’t know how to overwinter citrus.

Fast forward many years, while visiting Charleston, South Carolina, McKenzie saw a grapefruit tree loaded with golden grapefruit. “It lit the match again,” he says.

As he researched cold-hardy citrus he learned that satsuma trees are grown commercially in colder parts of Japan. It wasn’t long before he started growing satsuma. As his satsuma tree grew and prospered, everybody who saw the tree wanted one.

“That put me in the citrus business,” he says.

Cold-Hardy Citrus Tips

Overwintering Citrus Outdoors

McKenzie says that when overwintering in-ground citrus plants in borderline areas such as his, some citrus enthusiasts wrap the tree in a string of incandescent lights and then cover it with and insulating material. The lights give off enough heat to get the citrus plant through especially cold weather.

Another technique is “micromisting,” where a fine mist of water is sprayed over the trees. As the water freezes, it gives off heat—enough heat for the citrus plants to survive cold weather.

Overwintering Citrus Indoors

Where winter temperatures are more severe, people often bring potted citrus plants into the house over the winter. McKenzie says that the biggest challenge with this technique is that the air in most homes is too dry, causing the plants to drop leaves. The well-known Meyer lemon is especially finicky, he says. However, leaves will grow back in spring.

To maintain a higher humidity that is better suited to citrus plants, he recommends filling a tray (such as the foil trays sold for roasting turkeys) with pebbles and water. He says that spritzing with water regularly helps too.

Top Questions

Thorny growth at the base of the plant. McKenzie explains that many citrus are grafted onto a rootstock of trifoliate orange—a very thorny plant. Sometimes that root will send up a shoot, which, if left to grow, it will overtake the desired variety grafted onto it.

Wrinkled leaves and squiggly lines. He says that this is caused by an insect pest called the citrus leaf miner, which tunnels inside the leaf. While unsightly, they do no harm to the plant and do not affect the fruit.

Common Cold-Hardy Citrus

Prague Satsuma. This hardy satsuma survived the 8°F (-13°C) weater that killed many of the other satsuma varieties in his orchard.

Thomasville Citrangequat. McKenzie says that this cold-hardy citrus is a good lime substitute.

Crosses with trifoliate orange. He says there are many crosses with trifoliate orange that have excellent cold hardiness, but the fruit is usually bitter.

Yuzu, aka Japanese lemon, is very cold-hardy. He knows of people growing this citrus in colder areas such as Raleigh, North Carolina.

Poncirus Trifoliata (a.k.a. Trifoliate Orange)

The trifoliate orange, also known as trifoliate lemon and Poncirus, is extremely hardy, surviving in areas colder than USDA Zone 7. It is a common rootstock. McKenzie says that the small fruit are very seedy and bitter.

Connect with Stan McKenzie

Website: mckenzie-farms.com

Facebook: McKenzie-Farms-Nursery-174405135904728

Find Out How to Grow Your Own Lemons

Grow Lemons in Cold Climates Masterclass shows you how to grow a lemon tree in a pot or outside with protection. And get lemons!

Looking for More Citrus Information?

Canadian Garden Zones vs. US Garden Zones

Helen Battersby of torontogardens.com

We are joined by Helen Battersby, a Toronto garden blogger, garden coach, and publisher of the Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal.

She explores a topic that a lot of new gardeners are not even aware of—that there are different garden-zone systems used in Canada and the USA.

Always eager to push zone boundaries, Battersby finds that many gardeners live in a state of “zone denial.”

Garden Zones

Battersby talks about the difference between the Canadian and American garden zone systems—both of which provide gardeners with a zone number to use when selecting hardy plant material. The lower the number, the colder the garden zone.

She points out that while her garden is a zone 6 using the Canadian system, it’s a zone 5 using the American system.

The Canadian system uses a number of variables including lowest mean temperature of the coldest month, highest mean temperature of the hottest month, precipitation, and the number of frost-free days.

The American (U.S. Department of Agriculture, or USDA) zones are based solely on average annual minimum temperatures.

She likens the Canadian system to a Betamax; and the US systmem to the VHS.

TorontoGardens.com

Battersby and her sister, Sarah, run the award-winning blog torontogardens.com.

They started the blog at a time when a lot of Canadian gardening magazines were folding, with a goal of filling the gap left by the loss of the gardening magazines.

The Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal

The journal, in its 29th year, was started by Margaret Bennet-Alder. She entrusted the publication of the journal to the Battersby sisters when she was 90.

The journal was born out of tragedy. Bennet-Alder’s son David was diagnosed with schizophrenia. To track his medications and appointments, he created a booklet that had a pair of pages for each week. She saw his book with its seven weekdays, along with an empty eighth space. She decided to use that empty space for garden tasks. And so was planted the seed for The Toronto Gardener’s Journal.

Her son helped her refine the design and taught her how to use software for the creation of the first print run of 500. It became a meaningful project for the both of them.

Downtown Rooftop Edible Garden Gives a Breath of Fresh Air

Saskia Vegter, Urban Agricultural Co-ordinator at 401 Richmond

We’re joined by Saskia Vegter, the Urban Agricultural Co-Ordinator at 401 Richmond, a former industrial building that has been transformed into a cultural hub in a dense downtown Toronto neighbourhood.

Vegter, who previously worked in event management, felt drawn to work in horticulture.

"I just remembered the feeling of connection when my hands were in the soil.”

401 Richmond

401 Richmond is a former industrial building, built in 1899. Vegter explains that the currant owner restored the building to transform it into a cultural hub for artists and creative entrepreneurs.

Tenants currently include art galleries, a book publisher, a film festival, artists with studios, and a daycare.

The Rooftop Gardens

401 Richmond rooftop garden

The rooftop has three garden areas:

A deck-patio area, which includes trees and shrubs in containers

An extensive sedum green roof

The “mini farm,” which has fruit, vegetables, herbs, and flowers for cutting growing in containers

Tenants use the rooftop for meetings, lunches, to meditate—or just to get a breath of fresh air, says Vegter.

Children from the daycare often spend time on the rooftop, which provides the opportunity for activities such as herb tasting.

Rooftop Crops

Ultra-dwarf apple trees grow in the same containers as the chums (cherry-plums), with strawberry plants at the base

Luffa grows up the pergola

Planters with edibles are planned for edibility AND colour, using plants with ornamental properties

New to the garden this year is a fig tree

Wildlife on the Rooftop

Despite being on a rooftop in a downtown neighbourhood, Vegter says that there are lots of visitors. She laughs as she talks about the squirrel that left her gifts of half-eaten tomatoes during the summer.

She says that other wildlife includes swallowtail caterpillars, hummingbirds, honeybees, and ladybugs.

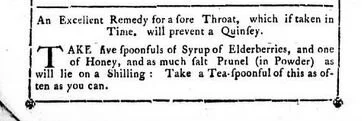

Elderberry: Forgotten Fruit Makes a Comeback

In our second chat with Kentucky farmer and author John Moody, we talk about elderberry.

Moody is the author of The Elderberry Book, in which he explores not only the cultivation and use of elderberry, but also it’s rich history.

Long History of Elderberry Use

Moody told his publisher, “I want to write a book about elderberry because it’s been almost 1,400 years since there was a book written about only elderberry.”

With his knowledge of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, Moody has been able to explore its use and lore in ancient texts.

There is a lot of story and lore involving elderberry in more recent times too. He points out that they can be found in Harry Potter, Monty Python, Shakespeare—and are even the subject of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale.

Elderberry on his Farm

Moody says that on his farm, each of his children is required to have a homestead business. His daughter Abby chose elderberry syrup—and the business has done extremely well.

Elderberry is in demand: He says that there is currently not enough elderberry to supply demand in North America.

Using Elderberry

Elderberry recipe from a calendar made in Nova Scotia, Canada in 1793

The elderberry fruit has many uses, including juice, tea, jelly, pie, and marinades.

The flowers can also be consumed, and are frequently used in teas, salads, and fritters.

But Moody says there is a rich history of use of medicinal use of other parts of the elderberry plant.

Top Tips for Growing Elderberry

Moody’s top three tips for growing elderberry:

Grow a number of varieties to determine which will be the most productive in your conditions

The least expensive way to get plants is by rooting hardwood cuttings

Elderberry is a moisture-loving plant, so give it a wet location, for example, near a downspout

Growing Citrus in Vancouver

Growing in-ground Meyer lemons, limes, and tangerines in Vancouver.

Greg Neal from North Vancouver tells us how he got the bug for growing citrus.

At last count he had 19 varieties around his suburban yard, some in the ground, some in pots, and some in his greenhouse.

He takes delight in seeing the look of surprise on the face of delivery people who notice lemons, tangerines, and limes growing in his front yard.

Lemons in Cold Climates

Neal says that memories of lemons growing around his aunt’s California yard inspired him to look into growing lemons at home.

He learned that Meyer lemons are quite cold hardy, and, seeing Meyer lemon plants for sale in 2006, came home with three plants.

He kept one plant in the house; it died. But the two that he stored in his cold garage for the winter lived.

He now grows Meyer lemon directly in the ground, covering it with a string of incandescent lights and fabric for winter protection. The lights emit just enough heat to get the plant through the coldest days.

He explains that the fruit takes about one year to mature—so it’s important to protect it from freezing over the winter.

His top tip for would-be lemon growers is not to grow them indoors.

Poncirus Trifoliata (a.k.a. Trifoliate Orange)

Neal grows trifoliate orange, which he says is mainly an ornamental.

Neal also grows trifoliate orange in his yard.

He explains that it is the most cold hardy of the citrus.

Unlike lemon, it drops its leaves for the winter.

With a laugh he says that some varieties of trifoliate orange are “sort of” edible, while with others, you think you’re being poisoned.

More on Cold-Climate Lemons

Looking for more information about growing lemons in cold climates? Head over to the Lemon Home Page.

Find Out How to Grow Your Own Lemons

Grow Lemons in Cold Climates Masterclass shows you how to grow a lemon tree in a pot or outside with protection. And get lemons!

Book: Growing Lemons in Cold Climates

If you’ve ever wanted to grow a lemon in a pot (or, in the ground if you’re in a borderline area), this book tells you how!

Getting Scrappy over Quince

Toronto master preserver and pastry chef Camilla Wynne joins us to talk about preserves—and about her Quince Scrap Jelly.

Wynne hates to waste quince scraps left over from making her quince ice cream because the scraps are full of flavour and pectin. The scraps are like gold to her because it’s hard to find locally grown quince in Toronto.

Wynne, the author of Preservation Society Home Preserves: 100 Modern Recipes, teaches preserving classes and writes a syndicated newspaper column about preserving.

Locally Grown High Pectic Fruit

Wynne is fan of currants, which contain lots of pectin. She explains that because of the pectin, getting a good set on jelly is quite easy.

“You’re never worried about not getting a set.“

She makes red currant syrup, which she says is nice served with sparking water or in cocktails.

She also uses red currant syrup to make Scarlett Pears, which are pears preserved in currant syrup. She explains that the pears take on a beautiful red colour.

When it comes to using quince jelly, she says it’s an excellent complement to cheeses, and is great for glazing meats. Or just enjoy it as jelly—it’s beautiful, with the pink colour that develops as it’s cooked.

In Search of the Elusive Colorado Orange

Jude and Addie Schuenemeyer

In a broadcast that originally aired on The Food Garden Life Radio Show, we chat with Jude Schuenemeyer from Colorado about the history of apple cultivation in Colorado, his work finding and preserving heritage apple varieties—and the recent “rediscovery” an a variety that he and his wife Addie have been working to track down and identify for 20 years: the Colorado Orange.

Schuenemeyer, a Sherlock Holmes of the apple world, scours historical horticultural records and talks to old timers, as well as using technology such as genetic fingerprinting.

The Colorado Orange

Schuenemeyer weaves together the threads of the story of the Colorado Orange, which include:

The influx of people to Colorado with the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush in the 1850s

A growing apples industry that fed these newcomers

The development of apples that would survive in the harsh conditions

Historical descriptions of the apple

Genetic testing

And, finally, finding a nearly forgotten set of wax apples that permitted the positive identification of the variety

Montezuma Orchard Restoration Project

With their passion for finding, saving, and sharing historical apple varieties, the Schuenemeyers eventually closed their nursery business and founded the Montezuma Orchard Restoration Project, a non-profit organization that works to preserve Colorado’s fruit-growing heritage and restore orchards to the culture and economy of the region.

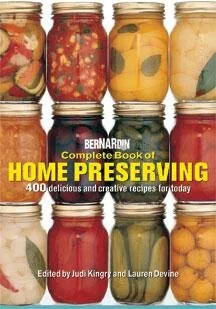

Emma’s Tomato-Talk Segment

We chat with Sarah Page about preserving tomatoes.

Page is a contributor to the latest version of the Bernardin Complete Book of Home Preserving: 400 Delicious and Creative Recipes for Today.

Page, who works as a recipe developer and tester, is a trained consumer chef and home economist. She loves creating new recipes with local and seasonal harvests.

Biggs-on-Figs Segment

We share questions and Answers from Steven’s Latest book, Growing Figs in Cold Climates: 150 of Your Questions Answered.

Preserving the Apple Harvest

Recipe developer and tester Sarah Page talks about preserving apples

We dig into the art and science of preserving—and talk about preserving apples— with Sarah Page, a contributor to the latest version of the Bernardin Complete Book of Home Preserving: 400 Delicious and Creative Recipes for Today.

Page, who works as a recipe developer and tester, is a trained consumer chef and home economist. She loves creating new recipes with local and seasonal harvests.

Preserving Tips

Two of Page’s top tips for successful preserving are:

Use a tested and approved recipe

Use fresh produce

And her tip for first-timers? “Don’t be intimidated at all!”

“If you can cook, you can can,” she says.

Sarah Page contributed recipes to the updated edition of the Bernardin Complete Book of Home Preserving

Apples

Page, who grew up in a household where her mother served applesauce regularly, loves to work with apples and shares a few of her favourite ideas:

Apple-cranberry butter

Preserving apples for pie filling later in the year

Apple sauce with a savoury flavour (e.g. chipotle)

Leaving the skin on pink apples when making apple sauce to give the sauce a pink colour

No Pectin?

Apples contain lots of pectin and sugar. Page explains that that makes them a useful addition when making jam with low-pectin fruit, because they can be used in place of commercially prepared pectin.

If you’re planning to preserve a lot of apples, Page says that an old-fashioned hand-crank food mill is a worthwhile investment.

Grow a Food Forest

Ryan Cullen, field supervisor at Durham College, talks about the new food forest at Durham College.

Make a Food Forest

We chat with Ryan Cullen, the field supervisor at Durham College, about the newly planted food-forest garden at the college’s Whitby campus.

Cullen oversees a diverse market garden that includes tree fruit, small fruit, cut flowers, field vegetables, greenhouse vegetables, and microgreens. He previously joined us on the show in Aug 2019. Click here to tune in to that episode.

Food-Forest Garden

Cullen explains that the idea behind the food forest is to grow a mix of food-producing species, layered in the same way that a forest is. There’s a herbaceous layer at ground level, a shrub layer, and a canopy layer of trees above.

With time, the food forest becomes self-maintaining and, with the appropriate mix of plant species, can have self-renewing fertility.

The top layer of the food-forest garden is the “canopy” layer. Cullen says that they planted this layer with fruiting tree species including cherries, plums, persimmon—and even a hawthorn.

The lower herbaceous and shrub layers, which are still being developed, will be a polyculture—a mix of different plants. Along with edible properties, plants in the lower layers might make available soil nutrients (deep-rooted plants bring up nutrients,) supply nutrients (pea shrubs capture nitrogen from the air,) and attract pollinator species.

Lower-layer plants include bee balm, chamomile, rosa rugosa (for rose hips), strawberreis, and blueberries. Cullen says that this list will grow, as there is still a lot of planting to do in this layer.

Food and Farming Program

The on-campus market garden is part of Durham College’s Food and Farming program, which focuses on urban and small-scale agriculture.

The program has a field-to-fork philosophy. Located on a former industrial site, the market garden produces a variety of vegetables and fruits to supply the on-campus restaurant, Bistro 67.

In addition to supplying the restaurant, the harvest also goes into a community-shared agriculture program (CSA) and farmers market.