Virtual Apple Tasting

Susan Poizner talks about the virtual apple tasting she recently held to raise money for her community orchard.

Fruit-tree educator Susan Poizner from Orchard People talks about holding a virtual apple-tasting event.

Stop and smell the roses? Community event helps people to stop and smell…apples.

Susan Poizner recently helped 50 Torontonians to stop and smell…apples. Poizner, a fruit-tree-care educator and college instructor with a passion for growing fruit trees, organized a virtual apple-tasting event as a fundraiser for her local community orchard.

Virtual Apple-Tasting Event

Poizner visited an orchard specializing in heirloom apple varieties to get enough apples for 50 participants.

Participants received a paper bag containing the six apple varieties for the tasting. Each was marked with coloured stickers for identification.

To help participants think about what they were tasting, the event was facilitated by an apple sommelier, a researcher specializing in taste perception.

Poizner explains that researchers testing new apple varieties for consumer acceptance might consider upwards of 50 things.

For this event, participants were asked to share feedback on four things:

Overall apple intensity

Honey

Floral

Green-Herbaceous

Want to know more about apple tasting? Check out this Apple Tasting Wheel.

Apple Varieties

The tasting event took attendees to different parts of the world with six heirloom apple varieties.

Kindel Sinap (Turkey)

Cranberry Pippin (New England)

Baxter (Ontario)

Empire (New York)

Melrose (Ohio)

Horneburger Pancake (Germany)

Thinking of holding a tasting event? READ MORE about an apple-tasting event in this article.

Grow Quince and Garden Journal

Nan Stefanik talks about growing quince. Helen Battersby talks about the Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal

Today: Nan Stefanik of Vermont Quince talks about how to grow quince. Helen Battersby talks about the 30th anniversary of a garden journal with a special story.

Grow Quince in Cold Climates

Imagine a job that revolved around a plant you’re passionate about. What plant would it be for you?

For Nan Stefanik that plant is quince.

She first tasted quince as an adult, on an overseas trip. After returning home, she was surprised to learn it grew locally in New England.

With a long history of its cultivation in New England, knowledge of quince had receded over time.

#GrowQuince

Stefanik’s business, Vermont Quince, makes quince paste, quince preserves, and other specialty quince products using New-England-grown quince.

Along with food products, she has made it her mission to collect and share quince information.

Using a specialty-crop grant, she started a #GrowQuince campaign to share quince-growing information.

Find more information about how to grow and how to cook quince on the Vermont Quince website.

What’s next? Stefanik and her son have acquired land for a quince education centre where they can combine a shop, demonstrations, and hold scion exchanges.

A fabric showing the different types of quince used in a recent quince taste test.

Toronto & Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal

Our second guest today is also passionate about what she does. Helen Battersby produces the Toronto and Golden Horseshoe Gardener’s Journal.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the journal, which includes information about frost dates, seed-starting dates, plant and seed sources — and also has space to record garden successes and failures.

There’s a deeply human story behind the journal, the story of a mother helping a son. Battersby shares that story, and talks about what’s new in the 2022 edition.

Compost Heater Heats a Hot Tub

Tom Bartels heats a hot tub and feeds his garden with wood-chip compost.

Tom Bartels heats a hot tub and powers his garden with wood-chip compost.

A wood-chip compost pile steams up this hot tub.

Today we visit a Colorado garden at an elevation of 6,500 feet. This episode co-hosted by Ryan Cullen, farmer at City of Greens.

Tom Bartels harvests 1,000 pound of fresh produce a year from his 1,300-square-foot garden, even though he has only 130 growing days.

Bartels uses a large amount of compost in his garden to maintain healthy soil. Much of that compost comes from wood chips.

But wood chips do more than feed his soil: They generate heat as they decompose. He can heat an outdoor hot tub through two Colorado winters with a pile of wood chips. No combustion is needed.

Heat from Wood Chips

Bartels says that many arborists pay to discard wood chips. By composting them, he removes them from the waste stream and gets both heat and compost for free.

The wood-chip pile used to heat the hot tub is approximately 6 feet tall and 12 feet in diameter. As he builds the pile, Bartels wets the wood chips and coils plastic piping within the pile.

The added moisture makes conditions suitable to microbial growth, while the water-filled plastic piping collects heat generated within the pile as microbes break down the wood chips.

Over two winters, the decomposing pile of wood chips generates the heat equivalent of burning 7 cords of wood. The temperature inside the pile gets as high as 150°F, and it stays warm enough to heat the hot tub for about 18 months.

From Heater to Compost

As microbial action slows down and the temperature within the pile drops, Bartels adds worms to speed up the composting process.

After another two or three months, the wood chips have been transformed into finished compost—worm castings—ready for the garden.

The wood chips that heated the hot tub for two winters are turned into 50 wheelbarrow loads of worm castings.

Tips for Wood-Chip Heating

Bartels explains that the right mix of wood chips makes the process work better. A blend of chipped coniferous wood as well as chipped small-diameter deciduous branches is ideal. This is because the small-diameter deciduous branches container more nitrogen—giving a ratio of carbon to nitrogen conducive to heat generation.

Here are Bartels’ wood-chip heating tips:

Have enough nitrogen in the pile. To be safe and make sure there’s enough nitrogen within the pile to give him good heat generation, Bartels says he adds about 5 per cent sheep manure. He also adds sawdust, which, he eplains, acts as a “bridge fuel” while the breakdown of the chips gets underway.

Have enough moisture in the pile. Bartels estimates that there are 4,000 gallons of water suspended within the pile. That’s a good thing because moisture is needed for optimal microbial activity. To keep moisture levels high, Bartels leaves the wood chips uncovered for the entire 18 months, allowing rain and snow to replenish moisture levels.

Greenhouse Wood-Chip Heating

Bartels sees opportunity for this sort of system beyond his demonstration hot tub.

He says that such systems are currently used to heat greenhouses and radiant floor heating systems.

Interviews

Grow Bamboo in Cold Climates

Bamboo expert Fred Hornaday on bamboo for cold climates.

Fred Hornaday talks about how to grow bamboo in cold climates, the many uses of bamboo — and its potential as an agricultural crop.

Fred Hornaday is bullish about bamboo and it’s many uses. From fuel to food to fibre, he sees it as a versatile crop with environmental benefits.

He shares his passion for bamboo through his bambubatu website, which has information about bamboo, how to grow it, how to use it, and its lore.

Many Uses of Bamboo

Bamboo is an extremely versatile crop that be be made into:

fabric

flooring

fuel

paper

food

mats

cutting boards

Bamboo in Cold Climates

There are many types of bamboo that survive in cold climates. Many of these cold-hardy bamboos are in the gemus Phyllostachys or Fargesia.

Bamboos in the former are “running” bamboos. Hornaday says most cold-hardy bamboos are running bamboos…those fast-spreading types that gardeners either love or hate.

But the Fargesia bamboos are clumping, making them desirable for gardeners not interested in containing their bamboo patch.

Bamboo as an Agricultural Crop

Hornaday is hearing from a lot of people interested in farming bamboo commercially in North America. At the moment, he says, there’s a need for processing infrastructure. Farmers growing bamboo for commercial processing could also harvest shoots as a specialty food crop.

As a perennial crop that can grow on marginal land, it can be used to stabilize soil.

Grow and Cook Bamboo

Wendy Kiang-Spray on how to grow and cook bamboo.

Wendy Kiang-Spray, author of The Chinese Kitchen Garden, talks about how to grow and cook bamboo.

Wendy Kiang-Spray’s children don’t recognize canned bamboo shoots. That says a lot about the difference between fresh bamboo and its canned cousin.

Kiang-Spray, author of The Chinese Kitchen Garden, grew up eating fresh bamboo, one of the many crops her father grows in his large garden.

She talks about growing, harvesting, and cooking bamboo.

Grow Bamboo

There are two groups of bamboo:

Running bamboos spread quickly by underground rhizomes.

Clumping bamboos grow in clumps.

Kiang-Spray points out that running bamboo might not be suited to small yards—at least not without measures to contain it. “It would be a big mistake in my suburban backyard; all my neighbours would hate me,” she says, as she talks about how quickly running bamboos can spread. A running bamboo spread to her yard from a neighbour’s yard over 100 feet away…not exactly a slow-growing plant.

To keep running bamboo in check she suggests:

Grow in containers

Plant on high berms (new shoots coming out the side will be easy to spot)

Instal a metal, plastic, or concrete barrier, buried to a depth of approximately 30 inches

Harvest Bamboo

Bamboo is harvested in the spring. Kiang-Spray says to use a knife — or to simply kick it over. “They should snap really easily,” she says, likening it to asparagus.

After harvest, cut shoots lengthwise and remove the edible “heart” by scooping it out with a thumb.

Fresh bamboo must be boiled prior to use to denature toxins. Boil uncovered for 30 minutes before use.

Urban Growers + Gardening Under Cover

Jamie Day Fleck talks about the urban growers she met while filming her documentary In My Backyard; and Niki Jabbour talks about garden covers and her book Growing Under Cover.

Filmmaker Jamie Day Fleck and author and broadcaster Niki Jabbour.

Today on the podcast we hear how one person’s journey into food gardening evolved into a documentary film — and then we find out how to use garden covers to take vegetable gardening to another level.

In My Backyard: A Documentary about Urban Growers

Torontonian Jamie Day Fleck converted her entire suburban backyard into a kitchen garden. That was the starting point of her documentary, In My Backyard, where she looks at ideas that urban growers have dreamed up in her hometown of Toronto.

Fleck talks about the urban growers she met while filming, how their gardens were different — and what they had in common. She also reflects on the future of urban growing.

Growing Under Cover with Niki Jabbour

We head to Halifax for food-garden inspiration from author, broadcaster, and vegetable gardening expert Niki Jabbour.

Jabbour talks about gardening in a polytunnel, reflects on her 2021 garden, and shares tips about how to use covers in the garden to grow more, protect crops from weather, and minimize pest problems.

Her newest book is called Growing Under Cover. It’s a must-have for serious vegetable gardeners.

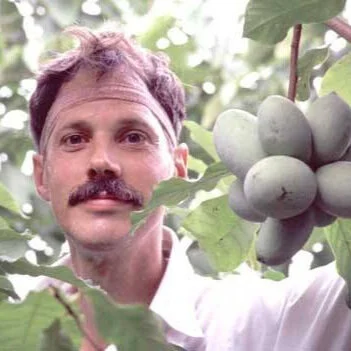

Pawpaw in Ontario with Paul DeCampo

Paul DeCampo talks about growing pawpaw in Ontario.

Paul DeCampo talks about pawpaw in Ontario: its history and how to grow it.

Pawpaw. It’s a fruit that has a long history in Ontario.

Yet it’s not well-known, nor do most people realize it grows wild in some parts of the province.

Paul DeCampo, Toronto’s pawpaw ambassador, planted his first pawpaw trees in 1994. “Nobody I knew had ever heard of this fruit,” he says.

Working in the food industry, he has had the opportunity to share his pawpaw fruit with chefs. Describing how, years later chefs will still talk about a fruit he gave them, he says, “Even if you’re someone who spends all day tasting the most interesting things, these are particularly astounding.”

Why Grow Pawpaw?

Pawpaw fruit from Paul DeCampo’s Toronto garden.

Besides the fact that the fruit is almost never available for sale, DeCampo says a pawpaw tree is a good fit for the challenges of a city yard.

That’s because:

Pawpaw does not require full sun

Pawpaw grows well under black walnut trees (which give off a compound that is toxic to many other plants)

There are very few pests that affect pawpaw

DeCampo’s Pawpaw Tips

DeCampo suggests thinking of a forest-edge garden when planting pawpaw. For urban gardeners, the shade of the forest is replaced by the shade of buildings.

Other tips:

Get three plants (two genetically-distinct plants are needed to get fruit…but nothing is certain in gardening, so DeCampo says to play it safe, and get three)

Life is short, so buy as large a tree as you can find and enjoy the fruit sooner

Pawpaw Resources

Plants: Grimo Nut Nursery

Books:

The Pawpaw Grower’s Manual for Ontario, by Dan Bissonnette

The novel The Overstory, by Richard Powers. The pawpaw is described as, “A sheepdog of trees;” the fruit having flesh that tastes like butterscotch pudding.

Doug Oster uses Newspaper Boxes to Share Seeds

Doug Oster uses Newspaper Boxes to Share Seeds

Doug Oster is using old newspaper boxes to share seeds with as many people as possible.

Where have all the newspaper boxes gone?

If you’re in western Pennsylvania, don’t be surprised if you find a dark green newspaper box with a sign in the window that says “Doug’s Free Seed Shack.“

Pittsburgh garden expert Doug Oster, a newspaper industry veteran, is using old newspaper boxes to get seeds to as many people as possible. He wants more people to garden. And he wants vegetable seeds easily available in communities where access to fresh produce is limited.

Having seen pictures online of seed-library boxes, he thought about doing something similar in his hometown of Pittsburgh.

Oster, who jokes about not being handy, decided building boxes wasn’t his thing. Instead, he repurposed old newspaper boxes. All it took was spray paint and a trip to the print shop for signs.

After the first summer of the project, Oster says he’s pleased with the results. The seeds are getting into the community. He’s getting good feedback. And people are asking if they can share seeds in the boxes, which is exactly what he wants. He wants the seed shacks to be like a library, where people can take seeds—but can also return seeds if they wish.

Tips for a Seed-Sharing Initiative

Oster says he needs to fine-tune the seeds he’s sharing through the boxes. He started by sharing what he knows, and what he thought would be useful to new gardeners. For example, he thought perpetual spinach—which has a long planting window, is easy to grow, and has a mild taste—was a great choice. But there was little interest in the perpetual spinach seed. What that taught him is that people often want to grow foods they know and love.

Oster’s tips for seed-sharing projects include:

Find a go-to person in the community who can let you know when a box needs refilling and can give insights on how to make it successful

Put it somewhere with good access, and where people feel safe

Don’t be shy about asking for sponsors

A Windy Newfoundland Homestead with a Sustainable Focus

David Goodyear talks about his homestead at Flatrock, Newfoundland.

David Goodyear

Old becomes new.

When David Goodyear began to think about food costs, sustainability, and how he and his family ate, he sat down with older relatives to hear how people used to eat. “Everybody ate root crops because they grew it themselves,” he was told.

Goodyear says there are many root crops that grow well in Newfoundland. It didn’t seem right when his grocery store had carrots from abroad. Nor did it didn’t seem sustainable.

Change in Diet Turns to Growing

Goodyear and his family started by changing their diet and eating more root crops. The food bill went down. They found more locally raised choices.

Then they decided to grow their own root crops.

Today they grow root crops, greens, tomatoes, strawberries…even figs. The next project? A food forest.

As Goodyear explains, his is a challenging climate. His town, Flatrock, is close to St. John’s, the third windiest city in the world. He has 110 frost-free days a year. “Winter starts in November; it doesn’t end till the end of May,” he says.

The focus on growing their own food led to an interest in storing the harvest. “If you’re going to grow a massive amount of root crops you need somewhere to put them,” says Goodyear as he talks about his root cellar.

Goodyear and his family switched up their diet; and have now switched up their life. Their homestead includes the gardens, a root cellar, a greenhouse, and a passive home.

How to Use Fig Leaves in the Kitchen

Chef David Salt talks about how to use fig leaves in the kitchen.

Chef David Salt explains how to cook with fig leaves. Salt’s restaurant is Drifter’s Solace.

Coconut. Almond. Green fig.

These are some of the flavours people use to describe what they taste when Chef David Salt serves something flavoured with fig leaves.

Salt cooked with fig leaves in London, England, where he had a ready source of fig leaves in a nearby churchyard.

Upon relocating to Toronto, he didn’t know where to find them.

And that’s when host Steven Biggs received an enquiry that read:

“I am looking for fig leaves to make dishes with at my restaurant (fig leaf ice cream, jelly, savoury sauces, custards etc.) Is there any possibility of getting some from you, before they fall for the winter?”

Salt got some fig leaves, and invited Biggs to the restaurant to taste his fig-leaf ice cream, fig-leaf cheese—and a fig leaf grappa!

Cooking with Fig Leaves

Salt says that the most classic method of using fig leaves is in the same way as banana leaves — as a wrap. When used as a wrap, they protect the enclosed meat or fish, keeping it moist. They also impart a unique flavour.

When cooking with fig leaves, the leaf is used to wrap food, or an infusion used to pull out the fig-leaf flavour.

The flavour is delicate. Salt finds it pairs well with light-flavoured meats or fish; and light-flavoured fruit such as strawberries and blueberries.

But he says to be creative: He’s paired fig leaves with hot chocolate, a strong taste, and found worked well.

His favourite dish made using fig leaves is ice cream.

For people using fig leaves for the first time, he explains that heat can help to bring out the flavour—but to avoid boiling, which results in a stewed-vegetable flavour. When time permits, a cold infusion is best.

Drifter’s Solace

Salt is gearing up to create fig-leaf flavoured foods this fall at his brand new chef’s-table style restaurant in Toronto. It’s called Drifter’s Solace.

Toronto has lots of big restaurants. Drifters Solace is at the opposite end of the spectrum: It’s small and personal, for groups of 6-8 people.

How to Forage for Mushrooms without Dying

Frank Hyman talks about how to forage for mushrooms.

Mushroom identification can be daunting for beginners, with Latin names and spore prints used to differentiate hard-to-identify mushrooms.

In his new book, How to Forage for Mushrooms without Dying: An Absolute Beginners Guide to Identifying 29 Wild Edible Mushrooms, Frank Hyman focuses on edible mushrooms that are easy to identify.

Easy-to-Identify Edible Mushrooms

Hyman suggests starting with easy-to-identify mushrooms when learning to forage — mushrooms that can easily be distinguished from non-edible ones.

Here are some of the mushrooms that he talks about in this episode:

Chicken of the Woods. “It will look like a pizza sticking our of a tree.”

Morel. Easy to distinguish from the non-edible false morel because the entire interior is hollow when sliced in half from top to bottom (the false morel has chambers within it.)

Black Trumpet (a.k.a. Horn of Plenty). These mushrooms, which look like little bugles, are hollow tubes. Pick it up and look through it length-wise, as if it were a telescope.

Giant Puffball. Slice in half to see that the interior is solid white. “If it’s white like a piece of tofu, you’re good to go,” says Hyman. If you see the outline of a mushroom within, or if it’s not white — don’t eat it.

More than Dinner

Hyman points out that along with the culinary uses of foraged mushrooms, there’s another reason people might consider foraging: It’s a fun outdoor activity; it’s time outdoors, in nature.

Backyard Chickens

Hyman is also the author of the book Hentopia: Create a Hassle-Free Habitat for Happy Chickens; 21 Innovative Projects.

Here is a video in which he talks about backyard chickens.

Are You Frightened of Landrace Gardening?

Joseph Lofthouse talks about landrace gardening and promiscuous tomatoes.

Joseph Lofthouse talks about landrace gardening and promiscuous tomatoes.

Joseph Lofthouse had hundreds of jars of seed around his house when he began market gardening.

He saved seeds from each variety…a time-consuming task.

Today he has far fewer jars of seed. Today he practices landrace gardening.

Lofthouse no longer focuses on keeping pure varieties, but instead uses genetically diverse lots of seed.

His is the author of the book, Landrace Gardening: Food Security through Biodiversity and Promiscuous Pollination.

What is Landrace Gardening

Landrace gardening is not new. It’s a traditional method of growing using locally adapted, genetically variable seeds. The genetic variability makes it more likely that some plants will perform well even if there are adverse conditions.

“What I’m doing was standard practice through all of human history up until about 60 years ago, until people started farming with machines instead of human effort,” explains Lofthouse.

How to Start Landrace Gardening

Not having pure varieties feels strange to some gardeners. But Lofthouse points out that uniformity isn’t important in small-scale operations or home gardens.

Here are his tips for gardeners who want to try landrace gardening:

Grow and save seeds of a favourite variety

Then grow another variety of the same crop with desirable traits next to it

Aim for 2 - 5 varieties of the same crop from which to start your landrace

Lofthouse notes that there are some crops for which he avoids certain mixes. For example, he does not mix his popcorn with his sweetcorn; or his hot peppers with his sweet peppers.

Helping Other People Eat through Gardening

Julie Brunson didn’t garden as a child, but began to garden and grow food as an adult. When her husband was in a dark place and found solace in their garden, the garden not only fed them, it helped him to heal.

That was the start of a journey into teaching kids about regenerative gardening, and also using the garden as a way to touch on a host of other topics including social justice, mental health, and nutrition.

Container Gardening with Hot Peppers - REWIND

Claus Nader from East York Chile Peppers on growing hot peppers in containers.

Claus Nader from East York Chile Peppers

Hot Peppers

What is the ideal plant for a small yard?

The ideal plant for someone wanting something ornamental – yet edible too?

And, just to complicate things, it has to be good for a garden where there are lots of squirrels.

Claus Nader found that hot peppers were that ideal plant.

Nader was gardening in a small yard that was frequented by marauding squirrels. While the squirrels sampled many of the things he grew, they didn’t eat his hot peppers.

So Nader made hot peppers the focus of his garden, growing them in pots on his balcony, deck, and dotted around his small yard.

Along with a passion for growing peppers in containers, Nader is also interested in unusual varieties and culinary uses and traditions. (His “Tummy Torch” sauce is magic on a piece of barbecued chicken.)

What's to Hate? A Look at the Whole Okra

Chris Smith, author of The Whole Okra, on growing okra, recipes, varieties.

Chris Smith, author of The Whole Okra, A Seed to Stem Celebration

Chris Smith remembers his first okra encounter well. It was at a diner in Georgia.

A native of the UK, where growing conditions are not conducive to heat-loving okra, the vegetable was foreign to him. So was the cuisine of the American south.

His recollection of that first taste of okra? Slime and grease.

While not enamoured by his first okra experience, a later gift of a dry okra seed pod—a pod with a story—ignited his interest in okra.

He began to grow it and to experiment with it in his own kitchen, using pods, leaves, flowers, stalks—even the seeds.

As that interest and his knowledge of okra grew, Smith started to teach others about it. In his quest for even more okra information, he’s spoken with food historians, researchers, farmers, and chefs.

He brings it all together in his book, The Whole Okra, A Seed to Stem Celebration.

Edible Front Yards and Sensory Gardens

Jennifer Lauruol on edible front yards, sensory gardens, and native plants

Regenerative-garden designer Jennifer Lauruol talks about edible front yards, sensory gardens, and native plants.

Jennifer Lauruol weaves together permaculture concepts, native plants, food plants, forest gardening, and educational elements in her regenerative-garden design work in Lancaster, England.

Her passion is edible ornamental gardening—especially in front yards.

Lauruol also uses many native plants in her designs. She finds that effective design helps people interpret the use of native plants as a garden.

Edible Front Yards

Lauruol recalls a neighbour’s concern that children might steal the fruit that Lauruol was growing in her front yard. Yet that was exactly her goal: that children would enjoy the fruit and learn where it comes from.

She says that a well-planned garden can have a succession of edible fruits and ornamental plants. Another way to weave edible plants into a landscape is to create an edible hedge.

While edible front gardens might not appeal to everyone’s taste, Lauruol does have a tip for gardeners worried about sceptical neighbours: “I do know what to do about the diehards: give them strawberries,” she says.

Native Plants

Lauruol explains that having a mown strip around plantings of native plants helps people understand it as something intentional. “If you create a frame around it then people can understand it,” she says.

Her own design with native plants is strongly influenced by Brazilian artist, painter, and landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx, who used big blocks of colour in his work. She says planting native plants in large drifts, as opposed to mixed plantings, is an approach that is less likely to be interpreted as sloppy.

Sensory Gardens

Lauruol creates sensory gardens for people with special needs. Her focus on sensory gardens stems from her own experience with her daughter Marie, who has special needs. “She comes alive when she is in nature,” says Lauruol, adding, “For me, the base of a sensory garden really needs to be a wildlife garden.”

Senses to stimulate with a sensory garden:

Sound. The sense of sound is often overlooked in garden design..

Sight. Lauruol likes to make colourful planting in the shape of a rainbow so visitors get a very strong sense of each colour

Taste.

Smell. “Different kinds of scent are like an orchestra,” says Lauruol. She says to remember scents other than floral scents, such as compost with its woody notes.

Touch.

Meet the Indiana Jones of Pawpaw

Neal Peterson hunted down lost pawpaw varieties to use for his pawpaw breeding work

Neal Peterson hunted down lost pawpaw varieties from the early 20th century to use in his pawpaw breeding work.

Meet Neal Peterson, the Indiana Jones of pawpaws. He was so moved by the taste of pawpaw that it became his life’s work.

There were improved pawpaw varieties in the early 20th century—but the fruit fell into obscurity.

Peterson dug through the literature to uncover past pawpaw breeding work, and then set out to track down lost varieties for use in his own pawpaw breeding work.

About Pawpaw

Peterson says that in the wild, pawpaws are an “understorey” tree, often growing in shade of larger forest trees. When they are in shady locations they become lanky and do not produce a lot of fruit.

But given more light, they produce much more fruit.

Two genetically distinct trees are needed to produce fruit.

Pawpaws sucker extensively, which can give rise to groves of pawpaw that are all clones from a single parent tree.

Peterson says that in the wild, pawpaw fruit can be quite seedy, with up to 25% seed by weight. In his work he has bred varieties with more fruit and less seed. His best variety has 4% seed by weight.

Pawpaws at Home

Pawpaw trees are well suited to a home garden, growing to approximately 20 feet high. While orchardists might space trees widely for equipment, home gardeners can reduce spacing.

Grow 2 in the space of 1: Peterson recommends planting two trees only a couple of feet apart if space is a challenge.

Choose a sunny site: While trees are shade-tolerant, they produce more fruit in sunny locations.

Minimize competition: Keep weeds and grass two feet away from the tree until it is well established

Keep soil moist: Mulch with compost to minimize weed growth and keep soil moist.

For cold climates: Choose early-ripening varieties such as ‘Shenandoah’ or ‘Allegheny’

Caution: Weed eaters can damage the bark.

Once established, pawpaw trees sucker profusely. If growing an improved variety that is grafted onto a rootstock, remove the suckers, which will be the same as the rootstock.

Grow Pawpaw from Seed

For gardeners who want to grow pawpaw from seed, Peterson notes that they are slow to germinate.

He suggests planting the seeds in the fall where they are to grow, or storing in the fridge in damp sphagnum moss in a sealed bag. They require a period of cold, moist conditions before germination.

Do not allow seeds to dry out because this will greatly reduce germination.

He says it can take 7 years until seed-grown trees flower.

Urban Farm Camp for City Kids

Urban Roots in Nevada uses gardening as a lens for teaching many other topics

Today on the podcast we head to Reno, Nevada to hear about Urban Roots, an organization that uses garden education to help change the way people eat. It takes gardens to classrooms…and uses the garden as a classroom at its urban teaching farm.

Fayth Ross and Elsa DeJong talk about the summer farm camp, programming for home-schooling families, and collaborations with local schools.

Farm Camp

During the summer and school breaks, Urban Roots runs programming for children at its urban teaching farm.

DeJong explains that there is a different theme each week. Themes include:

A bug’s life

Once upon a farm

All about bees

Woven into this farm camp curriculum are literature, art, engineering, music — and cooking.

Farm School

This program for home-schooling families takes place twice a week during the academic year, and includes lessons, games, and farm chores.

Choose-Your-Own-Adventure No Till

Jesse Frost on his choose-your-own-adventure approach to no-till

No-till expert Jesse Frost talks about soil and about choosing an approach to no-till suited to local conditions.

In this rebroadcast of the radio show that aired live on July 7th, we talk about soil and no-till practices with market gardener, farm journalist, and podcaster Jesse Frost.

He’s the host of The No-Till Market Garden Podcast, and he and his wife are no-till farmers at their Rough Draft Farmstead in Kentucky.

Frost’s new book is The Living Soil Handbook.

Choosing a No-Till Model

Frost says that there is no one-size-fits-all model of no-till growing.

It depends on the context — things such as soil, rainfall, climate, and the crops being grown.

No-till is as varied as the growers using it.

3 Principles to Grow By

A successful no-till system goes beyond not tilling.

Frost suggests three principles growers and gardeners can use to guide their approach to tillage:

Disturb the soil as little as possible

Keep the soil covered as much as possible

Keep the soil planted as much as possible

Coppices, Alcoholic Hedges, and Thoughts on Ecological Gardening

Matt Rees-Warren on ecological gardening, coppices, hedgerows, and schythes

Matt Rees-Warren talks about ecological gardening, scythes, coppicing, hedgerows — and pleachers.

Where is the sweet spot that gardening meets the natural world…so that gardening is ecological? Our guest today explains that ecological gardening is all about balance.

Matt Rees-Warren says, “Your garden is a pocket of wild; it will never be purely wild, because it’s an interaction between ourselves and nature. But it can be much more regenerative.”

Rees-Warren is a professional gardener and garden designer who’s passionate about the difference that individual gardeners can make to strengthen biodiversity and lessen environmental degradation.

He says gardening is one way individuals can make a tangible difference to the environment. Don’t wait for governments to act, he says. Start making changes now, in your own garden.

Rees-Warren is the author of The Ecological Gardener: How to Create Beauty and Biodiversity From the Soil Up.

Ecological Gardening

“If we design our gardens to be regenerative, the result will be functional, beautiful spaces full of life and vigour, robust enough to face the challenges of the future and elegant enough to beguile all those who walk among them,” says Rees-Warren.

But ecological gardening is more than a philosophy. There are many practical things we can do in the garden.

Here are some of the ideas discussed:

Coppicing. Talking about renewable materials for the garden, Rees-Warren explains the process of coppicing, where trees are repeatedly cut back to the ground to give a harvest of sticks that can be used in the garden.

Scythe. He describes this as “the most immersive” of tools. “It’s the only tool for wildflower meadows,” he says.

Hedgrows. Rees-Warren says hedgerows can also be food reservoirs, using plants such as blackberry, sloe berry, hops, raspberry, and hazelnuts. On the mention of sloe gin, he adds that sometimes these are called, “alcoholic hedges.”

Pleachers. “Laying a hedgerow” and the technique of using “pleachers” is one way to create attractive hedgerows that are like a living fence. Young trees are cut leaving just a thread of bark connecting them to the stem, and then folded down horizontally. “It looks fabulous,” says Rees-Warren.